Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia

Junctional ectopic tachycardia is a rare, often incessant, tachyarrhythmia due do to enhanced automaticity in the A-V node or bundle of His. There is generally a normal (narrow) QRS morphology with variable ventricular rates. If there are visible P-waves, the ventricular rate is greater than the atrial rate and it does not respond to pacing maneuvers or cardioversion, and is often difficult to control with milder antiarrhythmic medications.

Isolated junctional ectopic tachycardia is often familial. Some patients eventually develop complete heart block (105).

Most often junctional ectopic tachycardia is seen early, and temporarily following cardiac surgery in infants, and can result in significant hemodynamic compromise until it is controlled and abates. Intravenous amiodarone may be the best treatment; but cooling the patient down to 33 to 35 C with administration of intravenous procainamide is often helpful.

Atrial Flutter and Fibrillation

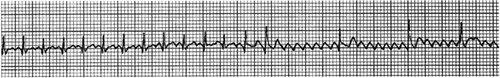

Atrial flutter is less common than other types of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in fetuses and neonates. It may be idiopathic, or associated with the same congenital heart lesions as those producing other supraventricular tachycardias. The atrial rate may be 200 to 500 beats/min. The AV node is generally not part of the tachycardia circuit, so that there need not be a 1:1 atrial:ventricular rate relationship. There is often some degree of AV node block resulting in variable conduction, frequently with a 2:1 or 3:1 atrial:ventricular relationship. With a 2:1 block, the ventricular rate at the highest atrial rate would be 250 beats/min, a rate sufficient to produce congestive failure in infancy. The RR interval is constant except when the atrioventricular block changes. The rare infant without AV nodal conduction block may have a very rapid rate and shock. With higher degrees of AV nodal conduction block, a sawtoothed atrial pattern is characteristically seen, often best in leads II or V1. In some patients the diagnosis can not be ascertained from the surface electrocardiogram, especially if there is a 1:1 atrial:ventricular rate relationship. Esophageal recordings may demonstrate the atrial

activity more clearly, or adenosine might be used to cause transient AV block and demonstrate the flutter waves. Adenosine, although diagnostically helpful, does not convert atrial flutter (Fig. 33-47). Digoxin can be used to slow the ventricular rate, but is unlikely to convert the atrial flutter. Overdrive atrial pacing from the esophagus and, if necessary, cardioversion by DC countershock (initial dose 0.5 to 1 Joule/Kg) can be used to convert the rhythm to sinus. In the absence of structural heart disease, there is generally a benign course once the arrhythmia is converted to sinus rhythm, and subsequent chronic antiarrhythmic therapy is often not necessary (106).

activity more clearly, or adenosine might be used to cause transient AV block and demonstrate the flutter waves. Adenosine, although diagnostically helpful, does not convert atrial flutter (Fig. 33-47). Digoxin can be used to slow the ventricular rate, but is unlikely to convert the atrial flutter. Overdrive atrial pacing from the esophagus and, if necessary, cardioversion by DC countershock (initial dose 0.5 to 1 Joule/Kg) can be used to convert the rhythm to sinus. In the absence of structural heart disease, there is generally a benign course once the arrhythmia is converted to sinus rhythm, and subsequent chronic antiarrhythmic therapy is often not necessary (106).

Atrial fibrillation is recognized by an irregularly irregular ventricular rhythm. It is rare in newborns and usually seen in patients with structural heart disease. Digoxin can be used to slow the ventricular rate. Cardioversion by DC countershock (initial dose 0.5 to 1 J/Kg) is usually necessary to convert a sustained episode.

Treatments for Supraventricular Tachycardias

Treatment depends in part on the mechanism of tachycardia (see Tables 33-18 and 33-19) (100). In arrhythmias involving the AV node, such as atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardias without or with the WPW syndrome, transiently slowing or blocking AV node conduction can terminate the tachycardia. Vagal maneuvers are often effective in terminating these types of supraventricular tachycardia. These include the application of ice or very cold damp cloth to the face and rectal stimulation. Ocular compression should not be used as a result of risks to the child’s vision.

Rapid bolus of intravenous adenosine (0.1 mg/kg, increased to 0.2 mg/kg if needed) is the treatment of choice for most infants with supraventricular arrhythmias involving the AV node that are refractory to vagal maneuvers. Adenosine is an endogenous nucleoside with a very short half-life that can transiently block AV node conduction, interrupting these arrhythmias, resulting in abrupt conversion to sinus rhythm. It is helpful to record the patient’s electrocardiogram during attempts at conversion so that one can see if there was an effect of the intervention on the arrhythmia. There also might be transient evidence of WPW syndrome as the AV node conduction is briefly blocked, in the form of a delta wave from antegrade conduction down an accessory conduction pathway. If there was transient termination with rapid resumption of the arrhythmia, a longer-acting agent might be necessary to control the arrhythmia. Significant side effects appear to be rare, but include initiation of atrial fibrillation. Rarely, in patients with WPW syndrome, this can cause a ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. It is therefore recommended that a defibrillator be readily available when administering adenosine. Methylxanthines (e.g., theophylline and caffeine) are competitive antagonists to adenosine, and might make dosing more difficult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree