Introduction to Adolescent Medicine

Alain Joffe

Adolescence refers to that stage of human development encompassing the transition from childhood to adulthood. The term adolescence (derived from the Latin adolescere, to grow into maturity) is broader in scope than the word puberty, which usually refers to the physical changes, including sexual maturation, that occur during this transition. Consequently, adolescence has not only physiologic but psychologic and sociocultural dimensions as well. To fully comprehend the significant events and transitions occurring during this period requires knowledge of each of these areas and of their interrelationships.

A thorough understanding of adolescence is important, not only in order to effectively address the health needs of this age group, but also because, in many ways, adolescence sets the foundation for the rest of the adult life-span. For example, virtually no individual begins to smoke cigarettes after age 20 and, conversely, individuals who become or remain obese during adolescence are likely to remain obese as adults. An estimated 65% of adult morbidity or mortality is determined by behaviors with onset or established during the second decade of life.

In 1990, approximately 35 million adolescents aged 10 to 19 years were living in the United States; this number is expected to grow to almost 50 million by 2040. Despite the projected increase in absolute numbers, the percent of the U.S. population comprised of 10- to 19-year-olds is estimated to fall from 14.5% in 2000 to 13% by 2020. Younger adolescents (those 10 to 14 years of age) will make up an increasingly greater proportion of the adolescent population and, by 2040, fewer than 50% of 10- to 19-year-olds will be non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Adolescence is viewed as both the healthiest period of life and the most problematic. For the majority of teenagers, the former is true, and they make the complex transition into adulthood without significant difficulty. In doing so, they accomplish or lay the groundwork for accomplishing several critical developmental tasks: becoming accustomed to a new and markedly changed body, formulating a personal and sexual identity, separating from parents, developing the capacity for intimacy in relationships, establishing a social identity, and preparing the foundation for economic independence.

Many teenagers fail to achieve one or more of these goals and suffer significant morbidity and mortality during this developmental period. Up to one-fourth of 10- to 18-year-old adolescents are at serious risk for school failure or of being injured or killed by various risky behaviors. The remainder are at lower risk but still face significant challenges to their health and optimal growth to adulthood. Mortality rates for 15- to 24-year-old adolescents decreased substantially since the 1950s, but have changed little from 1997 to 2000, the most recent year for which data is currently available.

Age-specific death rates are listed in Table 89.1. Unintentional injuries and homicide are the leading causes of death for young people aged 15 to 24 years. Suicide is the third leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-old males and the fourth leading cause for young women in the same age range. Homicide is the leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-old African American males and the second leading cause for 15- to 24-year-old Hispanic males. It is also the second leading cause of death for 15- to 24-year-old female African Americans, and the second or third leading cause of death among 20- to

24-year-old and 15- to 19-year-old female Hispanics, respectively. Over 5,000 young people aged 10 to 24 were homicide victims in 2000; although this number is much higher than in other industrialized countries, it represents a significant decrease (both in terms of absolute numbers and rates) since the third edition of this text was published.

24-year-old and 15- to 19-year-old female Hispanics, respectively. Over 5,000 young people aged 10 to 24 were homicide victims in 2000; although this number is much higher than in other industrialized countries, it represents a significant decrease (both in terms of absolute numbers and rates) since the third edition of this text was published.

TABLE 89.1. LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH AMONG YOUTH 10–19 BY RACE, ETHNICITY, AND GENDER (NUMBER OF DEATHS PER 100,000 IN SPECIFIED AGE GROUP) FOR 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Adolescent morbidity also is associated with risky behaviors and includes such problems as substance abuse (including alcohol and tobacco abuse), mental health problems, school failure and dropout, delinquency, sexually transmitted diseases and their sequelae (pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and adolescent pregnancy.

The rates of substance abuse, which had declined steadily from their peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s, began to climb again in 1992. Lifetime use of any illicit drug peaked in 1996 for eighth graders and in 1997 for tenth and twelfth graders. According to the 2002 Monitoring the Future Survey (http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/02data.html#2002data-drugs), the rates of drug use among eighth graders have declined significantly since then, but have remained relatively stable among tenth and twelfth graders. In 2002, 24.5% of eighth graders, 44.6% of tenth graders, and 53% of twelfth graders reported ever using an illicit drug.

Recent data concerning risky adolescent sexual behaviors are encouraging. According to the 2001 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS; http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/SS/SS5104.pdf) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the proportion of teenagers who have ever had sexual intercourse declined from 1991 to 2001. In 1991, almost 51% of high-school girls and 58% of high-school boys reported having intercourse; by 2001, the comparable figures were approximately 43% for high-school girls and 49% for high-school boys. The number of students reporting four or more lifetime sexual partners also decreased. More than 50% of sexually active girls and 65% of sexually active boys reported condom use at last intercourse, a significant increase over the last decade. Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates among 15- to 19-year-old girls have all substantially declined in the last decade; this is likely due to a decrease in sexual activity coupled with increased access to a wider range of effective contraceptive methods. However, the rates of sexually transmitted infections such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae continue to be highest among young people age 15 to 24. More ominously, mathematical modeling suggests that 50% of new HIV infections in the United States occur in people under the age of 25, with most acquired sexually.

From a mental health perspective, the 2001 YRBSS indicates that 14.2% of males and 23.6% of females had seriously considered attempting suicide in the 12 months preceding the survey; 6.2% of males and 11.2% of females had actually attempted suicide, with 2% of males and 3% of females surveyed requiring medical attention as a result of their attempt.

Although anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are viewed as the stereotypical nutritional disorders among adolescents, overweight and obesity are far more common. The prevalence of overweight among 12- to 19-year-olds increased from 6%

in the early 1970s to 15% by 2000. Although the etiology of overweight is multifactorial, a decline in physical activity and an increase in television viewing and other sedentary behaviors are significant factors.

in the early 1970s to 15% by 2000. Although the etiology of overweight is multifactorial, a decline in physical activity and an increase in television viewing and other sedentary behaviors are significant factors.

Since the late 1970s, research examining the etiology of risky behaviors consistently demonstrates that these behaviors are not distributed randomly among adolescents. It is important to recognize that some risky behaviors fulfill the developmental needs of adolescents (e.g., testing the limits of a newly matured body or separating from parents). Others have their roots in the adolescent’s individual characteristics (e.g., temperament, sensation-seeking) or in his or her social context (including family, school, community, and socioeconomic status). As a result, some adolescents are at greater risk for adopting risky behaviors than others. Moreover, risky behaviors often coexist within an individual (e.g., a young person who smokes cigarettes is more likely to engage in sexual intercourse and to use other drugs).

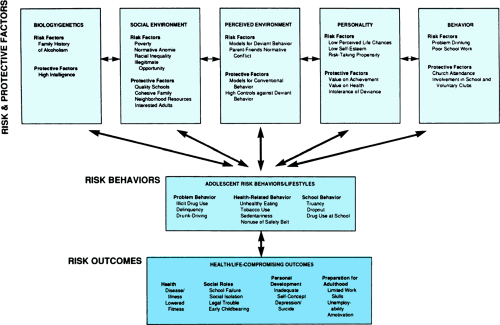

Unfortunately, this pattern of risky behaviors has fostered a negative stereotype about adolescents. In contrast, more recent adolescent health research, exploring the related concepts of resiliency and youth development, has cast a much more favorable light on this period of development. Resiliency research focuses on adolescents who live in circumstances that would seem to predict negative outcomes, yet these adolescents survived or even thrived. It identified protective factors such as aspects of the adolescent’s temperament, spirituality, feeling connected to family, and/or the ability to seek out a caring extrafamilial adult. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health revealed that an adolescent’s perception of being connected to family and school were protective against seven of eight risky behaviors assessed in the study. The interplay among resiliency and risk is shown in Figure 89.1.

The youth development framework also assumes a positive view of adolescents. Its basic assumption is that young people have a fundamental need for healthy development that requires a variety of experiences or circumstances that support the youth’s development from a child into an adult. These include an environment that provides a sense of personal involvement and belonging and of confidence and security. One proposed list of developmental assets can be found at http://www.search-institute.org/assets/. Both the resiliency and youth development models have dramatically reshaped the prevailing view of adolescents, from problems that must be fixed or contained to resources that deserve careful and deliberate nuturing.

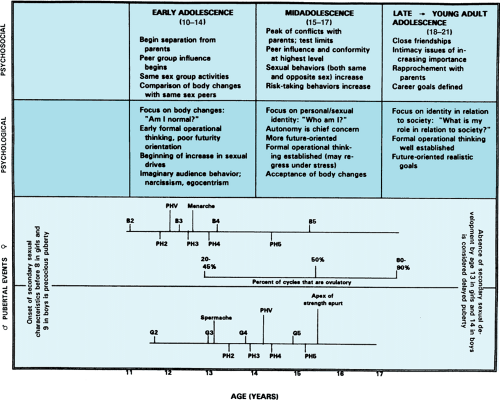

Thus, the goals of adolescent medicine are twofold: to support adolescents in making a successful transition to adulthood and to encourage healthy lifestyles that promote longevity and well-being for the duration of the human life-cycle. Insight into the nature of the statistics that characterize the dimensions of adolescent health and the potential for improving it comes from a knowledge of the marked biologic and psychologic changes that occur during puberty, as well as from an appreciation of the magnitude of change that has taken place in society. Each of these related areas is discussed separately. A schematic representation of the ensuing discussion is shown in Figure 89.2.

BIOLOGIC CHANGES

Hormonal changes associated with sexual maturation begin before any physical signs of puberty are evident. An increased production of adrenal sex steroids (adrenarche) occurs approximately 2 years before maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Presumably because of a decreased sensitivity to the negative feedback system between the central nervous system and the testes or ovaries, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland begin to secrete increased amounts of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone (LH). This increase is apparent only during sleep in early pubertal adolescents, but by mid puberty it becomes established during the day as well. The sleep-enhanced LH secretion occurs in agonadal patients, indicating that this process results from maturational changes at the level of the central nervous system and hypothalamus, rather than through changes in the gonads.

Secondary to an increased secretion of pituitary hormones, serum levels of testosterone in boys and estrogens (estradiol) in girls increase progressively during physical maturation. Increased secretion of growth hormone becomes established by mid-puberty. By mid to late puberty, a positive feedback system involving LH and estrogen production leads to an estrogen-induced mid-cycle LH surge and ovulation. The physiologic roles of the various hormones during puberty are shown in Table 89.2.

Tanner’s classic studies detailing the growth of adolescents and development of secondary sex characteristics established the foundation for the concept of Tanner stages (or sexual maturity ratings). Boys are assigned separate ratings for both genital and pubic hair development, girls for pubic hair and breast development. Most events occurring during adolescence correlate more closely with sexual maturity rating or skeletal age than with chronologic age.

It is important to note that some pubic hair development can occur through stimulation of hair follicles by adrenal androgens; hence, testicular enlargement and breast development are the more reliable markers of pubertal onset. The various stages of pubic hair development in boys and girls and testicular development in boys is shown in Figures 89.3 and 89.4.

Breast development in girls occurs in the following sequence: early on (stage B2), breast tissue (which can be extremely firm) is palpable only under the areola; in stage B3, the breast tissue extends beyond the areola to form a distinct mound; at stage B4, the areola and papilla form a secondary mound distinct from the underlying breast tissue; and at stage B5, the areola and breast tissue again form a smooth contour (no separation of areola and breast tissue).

Breast development in girls occurs in the following sequence: early on (stage B2), breast tissue (which can be extremely firm) is palpable only under the areola; in stage B3, the breast tissue extends beyond the areola to form a distinct mound; at stage B4, the areola and papilla form a secondary mound distinct from the underlying breast tissue; and at stage B5, the areola and breast tissue again form a smooth contour (no separation of areola and breast tissue).

TABLE 89.2. PRIMARY ACTION OF MAJOR HORMONES OF PUBERTY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Studies indicate a definite sequence of pubertal events that most adolescents pass through as they mature. Although the sequence is the same, the age at onset of these events and the time interval between events vary. On average, puberty lasts approximately 3 to 4 years, but the range is quite variable. Among girls, full development of breast tissue averages 4 years, but the fifth percentile is 1.5 years and the ninety-fifth percentile is almost 9 years; the average time span for pubic hair development is 2.5 years, with the range being 1.4 (fifth percentile) to 3.10 years (ninety-fifth percentile). Among boys, complete development of the testes can take as little as 1.86 years or as much as 4.7 years (average 3 years); complete development of pubic hair can take less than a year or as long 2.67 years (average just over 1.5 years).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree