On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

understand the reasons behind selection of cannula size and site

appreciate alternatives to peripheral cannula placement

understand fluid, blood and clotting product administration and monitoring in routine and complex clinical situations.

Intravenous access

Intravenous access is best achieved by inserting as large a cannula as possible into a large peripheral vein. Short, wide-bore cannulae deliver the fastest flow. The Hagen–Poiseuille equation describes the factors affecting the flow through a tube.

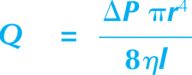

Where Q is flow, ΔP is pressure drop across the two ends of the tube, r is the radius of the tube, ƞ is viscosity of the fluid and l is the length of the tube. The major variables we can control are ΔP, r and l.

The effect of ΔP can be demonstrated most simply by increasing the height of the infusion fluid above the patient. This will result in an observed increase in flow rate through the cannula. Simple pressure bags and more complex pneumatically controlled rapid infusion devices are available to maximise the effect on ΔP and subsequently flow rate. Great care must be taken with these devices to ensure the vein does not become damaged by the high pressure, with subsequent extravasation of fluid into the extravascular tissues, as well as the risk of delivering too much fluid too rapidly causing circulatory overload.

Because r is affected by the power 4, relatively small increases in internal diameter will have major changes on achieved flow rates. Table 7.1 demonstrates the effect on flow rates of increasing the diameter of the cannula. The length of the cannula (l) should be short to optimise rapid fluid administration.

| Cannula gauge | Flow rate (ml/min) |

|---|---|

| 22 | 36 |

| 20 | 61 |

| 18 | 96 |

| 16 | 196 |

| 14 | 343 |

Veins in the forearm in the obstetric patient are often large and have the benefit of not traversing a joint and therefore being easier to protect from the effects of movement. Otherwise, large veins in the antecubital fossae may be good sites for placement of peripheral intravenous cannulae for emergency fluid administration, with care taken to ensure an artery is not cannulated in error. Splinting and good fixation will be needed.

Types of large-bore cannulae

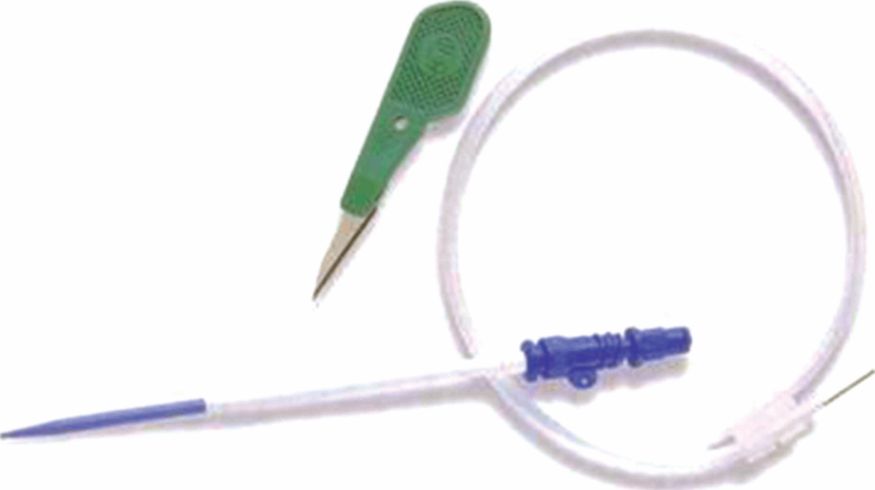

Obstetric haemorrhage can be catastrophic and extremely rapid. Intravenous devices exist (e.g. Arrow Peripheral Emergency Infusion Device [EID™] or Rapid Infusion Catheter [RIC®]) that can increase the flow rate to four times that seen through a 16-gauge cannula (Figure 7.1). The EID uses a small-gauge ‘seeker’ needle to permit venous puncture in patients with poor peripheral perfusion. The built-in Seldinger (guide wire) technique then allows the 6 French gauge infusion catheter to be railroaded into the vein. The RIC allows the existing peripheral access to be converted, 20 g or greater, to a 7 French gauge catheter. A Seldinger exchange wire is threaded through the existing venous access, once patency of the cannula has been established. The cannula is then removed, leaving the wire in place within the vein. The infusion catheter is then threaded over the wire to establish large bore peripheral venous access.

Rapid infusion, large gauge, short bore devices are also available for central use that make the delivery of vast amount of fluid possible in the face of torrential haemorrhage.

Alternatives to peripheral venous access

Intraosseous access

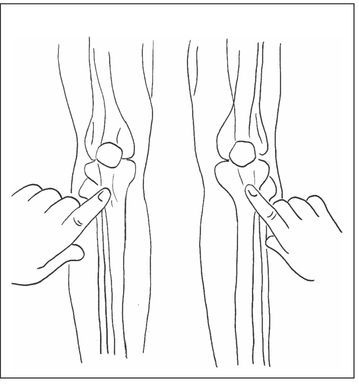

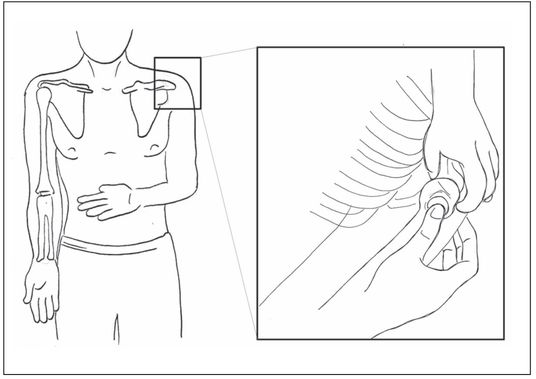

In extreme situations, the placement of intravenous cannulae may not be possible. The intraosseous (IO) technique is quick and relatively simple, particularly when assisted by a powered insertion device (Figure 7.2). This skill is taught during the face-to-face element of the MOET course.

| Tibial | Humoral |

|---|---|

| Anterior surface, 2 cm below and slightly medial to the tibial tuberosity. | Position arm with elbow close to side, with forearm flexed so hand resting on abdomen. Anterolateral surface, 1 cm above the greater tubercle (use only in patients where landmarks can be clearly identified). |

|  |

Uses for IO cannulae:

the administration of drugs

the administration of fluid

the aspiration of marrow, which can be used for crossmatching blood.

It must be remembered that fluid will need to be administered under pressure, as gravity alone will not be sufficient to provide adequate flow through the IO cannula.

Contraindications to use of IO cannulae:

fracture proximal or distal to insertion site

previous orthopaedic surgery at the site

infection at the puncture site

previous IO access within 24 hours at the same site should preclude the use of IO

needles at that site

the inability to palpate bony landmarks.

Figure 7.2 shows the commonly used sites for access. The humerus has advantages, in terms of flow rate and physical ease of access to the site. However, it may be covered with excessive tissue, making it impossible to establish IO access there. In this situation, it may be possible to gain access at the tibial site, where fat deposition is usually less marked. IO cannulae are available in 15, 25 and 45 mm lengths and should be chosen appropriately for the estimated amount of subcutaneous tissue to be punctured.

Complications of insertion:

can become dislodged with subsequent high-volume infusion into the tissues

compartment syndrome as a result of above

sinus formation

failure to deliver essential drugs and fluids

infection leading to osteomyelitis.

The infection risk can be minimised by correct skin preparation, occlusive dressing and aseptic nontouch techniques when using the cannula. Modern needles can be inserted using a rapid access ‘gun’ with purpose-made occlusive dressings that are more secure. This will be demonstrated on the course.

While insertion of the IO cannula using the gun is relatively painless, running in the fluid can cause significant pain and local analgesia may be required. By contrast, the handheld IO needles do cause pain on insertion and, unless the patient is in extremis, local anaesthetic should be used both in the skin and above the periosteum before the needle is put in place.

CVP line access

A CVP line may help to avoid either under-transfusion or fluid overload. This requires the placement of an intravenous catheter into the central circulation. Placement is achieved most commonly by the internal jugular vein approach or from a peripheral vein in the arm using a much longer catheter. The latter is especially useful for monitoring in cases with severe DIC, as the risk of bleeding at insertion is small. However, these devices are usually single lumen and therefore only of use for monitoring. If infusion of centrally acting drugs or fluids is required, a multilumen catheter is usually placed in the internal jugular or the subclavian vein.

Femoral vein access

Access to the femoral vein is less used in the obstetric patient. Ease of access will vary hugely with the degree of obesity and the size of the uterus and may be rendered useless if obstetric manoeuvres in the lithotomy position are required. It should not be discounted in a crisis, as it can provide quick access to a central vein without requiring a head-down position or interfering with the airway. However, there is the concern of exacerbating haemorrhage from infusing fluids into the venous system that is actively bleeding.

Practical tips for use of CVP lines:

the staff looking after them should receive training in their use

the transducer should be zeroed at approximately the level of the heart

the flush bag needs to be maintained at an adequate pressure, usually 300 mmHg pressure to avoid flow backtracking down the line, 300 mmHg is conventionally used and provides a steady infusion of 2–3 ml per hour via a flushing device

heparin-containing flush bags are not usually required

care needs to be taken to ensure all ports on the three-way taps used are capped to avoid an air embolus when the woman inhales

care on removal of the device to maintain closed caps, a supine position and pressure over the site to avoid an air embolus

strict asepsis when taking samples or giving drugs to avoid infected lines and subsequent bacteraemia

removal as soon as no longer needed to reduce risk of infection or venous thrombosis.

Ultrasound-guided access

The rise in availability of portable ultrasound machines has seen huge uptake of use among anaesthetic practitioners. This technique allows direct visualisation of the vein to be cannulated. The operator can observe puncture of the vein by realtime ultrasound guidance, thus reducing the risk of inadvertent arterial cannulation or failed venous access. In the absence of adequate peripheral intravenous access, many anaesthetists would choose to use this technique to gain access to a central vein.

Ultrasound has also gained popularity in siting peripheral access cannulae in morbidly obese or oedematous women. Anatomical landmarks can be scanned to find veins, assess depth and observe direct puncture of veins that are not visible or palpable on the surface of the skin.

Intravenous fluid administration

Circulatory volumes

In everyday obstetric practice, the commonest reason for urgent fluid administration will be in the face of maternal haemorrhage. For that reason, the bulk of this section is written in the context of maternal bleeding unless otherwise commented on.

During pregnancy, we see an increase in circulating volume of approximately 40%. This means the volume increases from 70 ml/kg to 100 ml/kg, or 4900 ml to 7000 ml in a 70 kg woman. It is this expansion in circulating volume that allows the mother to compensate extremely well for blood loss; it is also the reason why we sometimes underestimate the severity of blood loss, occasionally even until the point of maternal collapse, and the signs and symptoms produced only become obvious and dramatic with life-threatening blood losses.

Maternal blood loss can be categorised into four classes of increasing severity (see Table 5.1). It is worthy of note that absolute blood loss in a smaller woman reflects a larger percentage loss of her circulating volume.

Fluid warming and pressure devices

All intravenous fluids should be warmed when their administration is rapid. The rapid administration of large volumes of cold fluid will lead to significant hypothermia. Note: it is dangerous to infuse cold fluid directly into the heart through a CVP line. There are numerous fluid warming devices available; more advanced models offer co-axial heated tubing to ensure the temperature of the fluid is maintained right up to the point of delivery in to the cannula.

Reduced maternal temperature will cause shivering in an attempt to raise body temperature resulting in an increased oxygen demand. Failure to meet this demand will increase anaerobic metabolism and metabolic acidosis. Peripheral vasoconstriction, in an attempt to reduce any further heat loss from the periphery, will also lead to decreased oxygen delivery to the tissues, which will further add to metabolic acidosis. Significant drops in temperature will also have profound effects on the efficacy of the coagulation cascade and contribute to problems with clot formation.

High-pressure infusion devices are essential. Hand-inflated pressure bags are effective but labour intensive. Hazards of any high-pressure infusion include fluid overload and air embolism.

Types of intravenous fluid

Crystalloids

Crystalloids contain small molecules therefore they exert little oncotic pressure. As a result, these fluids distribute outside the intravascular compartment with ease, making their use in volume correction transient. They are physiological solutions and remain in the circulation for about 30 minutes, before passing into the extra- and intracellular spaces. An overload may cause pulmonary and cerebral oedema (so care is needed in pre-eclampsia/eclampsia).

They are useful for the immediate replacement of lost volume in the haemorrhage situation. They are also the mainstay of fluid administration in most other circumstances, as will be discussed in the remainder of this chapter.

Hartmann’s solution

Also known as Ringer’s lactate or compound sodium lactate, this fluid is often the crystalloid of choice. Its ionic composition is closely matched with that of plasma.

0.9% sodium chloride (‘normal’ saline)

The excessive use of solutions of sodium chloride can result in hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis and clinicians should be aware of this, and avoid their use in large volume when possible.

Dextrose solutions

Dextrose within these fluids is rapidly metabolised by the body. The remaining fluid is there- fore water, which is free to rapidly distribute into intracellular tissues. This increases the risk of cerebral and pulmonary oedema. The use of dextrose solutions should therefore be reserved for the treatment of specific conditions, such as hypoglycaemia, or (in conjunction with saline) with intravenous insulin regimens to maintain glucose homeostasis in diabetic women.

Use of large volumes of hyponatraemic solutions is dangerous and can result in rapidly lowering serum and intracellular sodium levels leading to tissue oedema. Restoring sodium levels from extremes to normal is also a hazardous activity and expert advice must be sought urgently. Should a woman present with a very low serum sodium, the restoration of sodium levels must be very cautious under the guidance of an intensivist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree