Obstetric Forceps

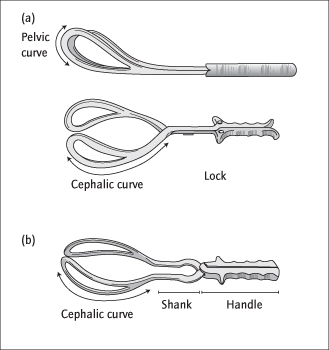

These come in pairs that fit together for use. Each has a ‘blade’, shank, lock and handle. When assembled, the blades fit around the fetal head and the handles fit together (Fig. 31.2). The lock prevents them from slipping apart. Non-rotational forceps (e.g. Simpson’s, Neville–Barnes) grip the head in whatever position it is and allow traction. They are therefore only suitable when the occiput is anterior. These forceps have a ‘cephalic’ curve for the head and a ‘pelvic curve’ which follows the sacral curve. Rotational forceps (e.g. Kielland’s) have no pelvic curve and enable a malpositioned head to be rotated by the operator to the OA position, before traction is applied.

Safety of Ventouse and Forceps

Failure:

Both methods of delivery can fail: this is more common with the ventouse, particularly if the cup is placed inaccurately.

Maternal complications and the need for analgesia are greater with forceps, but use of either instrument can cause vaginal laceration, blood loss or third-degree tears [→ p.261]. Cervical and uterine tears are very rare.

Fetal complications are slightly worse with the ventouse. An unsightly ‘chignon’, a swelling of the area of scalp that was drawn into the cup by suction is usual. It diminishes over a period of hours, but a mark may be visible for days. Scalp lacerations, cephalhaematomata and neonatal jaundice are more common with the ventouse. Facial bruising, facial nerve damage and even skull and neck fractures occasionally occur with injudicious use of forceps, and prolonged traction by either instrument is dangerous.

Changing Instrument:

This is associated with increased fetal trauma, and is usually only appropriate if a ventouse has achieved descent to the pelvic outlet, but then comes off the head and is replaced by a low cavity forceps delivery (see below).

Indications for Instrumental Vaginal Delivery

Prolonged second stage is the most common indication. Instrumental vaginal delivery is usual if 1 h of pushing (active second stage) has failed to deliver the baby. If the mother is exhausted it may be performed earlier. The length of passive second stage is less important.

Fetal Distress:

This is more common in the second stage: delivery can be expedited.

Prophylactic use of instrumental vaginal delivery is indicated to prevent pushing in some women with medical problems such as severe cardiac disease or hypertension.

In a breech delivery [→ p.229], forceps are often applied to the after-coming head to control the delivery.

Prevention of Instrumental Vaginal Delivery

Whilst the ventouse and forceps have clear benefits, e.g. delayed second stage, avoidance of such circumstances is preferable.

All Labours:

Continuous support [→ p.247] is essential (Cochrane 2011; CD003766), and delivery should be in the most comfortable maternal position possible. Epidural analgesia, cardiotorography (EFM) [→ p.253] and, probably, induction predispose to instrumental delivery.

Where Epidural Analgesia Is Used:

In spite of the excellent analgesia and consequent popularity, epidural analgesia increases the risk of instrumental delivery (AmJOG 2002; 186: S69): if used, maternal pushing should be delayed at least an hour after the diagnosis of second stage unless the head is visible, oxytocin should be considered if descent of the head is poor (only in nulliparous women), and pushing should be directed.

Types of Instrumental Vaginal Delivery

The type of delivery and choice of instrument is determined by the position and descent of the head: no instrument should be regarded as ‘first choice’ for all situations, but an overall comparison of forceps and ventouse is shown on p. 273. With either instrument, if moderate traction does not produce immediate and progressive descent, Caesarean section is indicated. ‘High’ forceps deliveries (the head is not engaged) are dangerous and obsolete. Caesarean section at full cervical dilatation is increasingly used as an alternative to instrumental delivery. However, it is often difficult surgically and is associated with increased maternal trauma and neonatal unit admission (Lancet 2001; 358: 1203): skill with forceps remains essential.

Low-Cavity Delivery

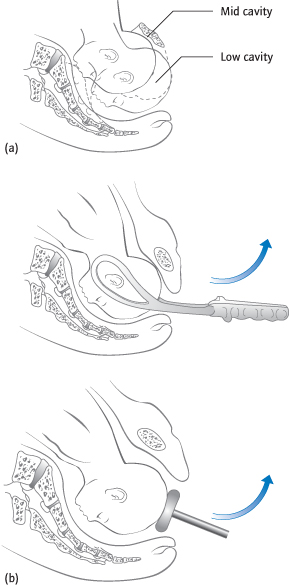

The head is well below the level of the ischial spines, bony prominences palpable vaginally on the lateral wall of the mid-pelvis [→ p.239] and is usually occipito-anterior (OA) (Fig. 31.3a). Forceps or a ventouse are appropriate (see box), the former being better if maternal effort is poor. A pudendal block [→ p.257] with perineal infiltration is usually sufficient analgesia.

Fig. 31.3 (a) Side view of pelvis showing level of head for mid-cavity and low-cavity forceps delivery. (b) Forceps and ventouse in position on the fetal head showing direction of traction.

Mid-Cavity Delivery

The head is still not palpable abdominally, but is at or just below the level of the ischial spines (Fig. 31.3a). Epidural or spinal anaesthesia are usual. If there is any doubt that delivery will be successful, it is attempted in the operating theatre, with full preparations for a Caesarean section. This is called a ‘trial’ of forceps or ventouse. The position may be OA, occipito-transverse (OT) or occipito-posterior (OP) [→ p.242].

Occipito-Anterior Position:

Forceps or a ventouse can be used.

Occipito-Transverse Position:

Usually this is a result of insufficient descent of the head to make it rotate. Therefore, descent is achieved with the ventouse, with rotation resulting. Non-rotational forceps are contraindicated. Rotation in situ followed by descent can also sometimes be achieved by manual rotation or with Kielland’s rotational forceps (see below).

Occipito-Posterior Position:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree