Chapter 627 Injuries to the Eye

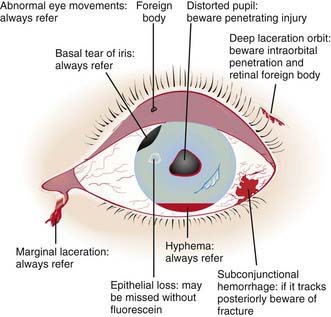

About 30% of all blindness in children results from trauma. Children and adolescents account for a disproportionate number of episodes of ocular trauma. Boys ages 11-15 yr are the most vulnerable; their injuries outnumber those in girls by a ratio of about 4 : 1. The majority of injuries are related to sports, toy darts, other projectiles, sticks, stones, fireworks, paint balls, and air-powered BB guns. The last causes particularly devastating ocular and orbital injuries. Much of the trauma is avoidable (Chapter 5.1). Any part of the orbit or globe may be affected (Fig. 627-1).

Figure 627-1 The injured eye.

(From Khaw PT, Shah P, Elkington AR: Injury to the eye, BMJ 328:36–38, 2004.)

Foreign Body involving the Ocular Surface

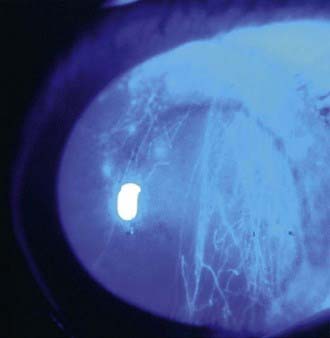

A foreign body usually produces acute discomfort, lacrimation, and inflammation. Most foreign bodies can be detected by examination in good light with the aid of magnification or a direct ophthalmoscope set on a high plus lens (+10 or +12). In many cases, slit-lamp examination is necessary, especially if the particle is deep or metallic. Some conjunctival foreign bodies tend to lodge under the upper eyelid, causing the sensation of corneal foreign body as they come into contact with the globe on eyelid movement; they can also produce vertically oriented linear corneal abrasions (Fig. 627-2). Finding these abrasions should lead to a suspicion of such a foreign body, and eversion of the lid may be necessary (Chapter 611). If a foreign body is suspected but not found, further examination is indicated. If the history suggests injury with a high-velocity particle, radiologic examination of the eye may be needed to explore the possibility of an intraocular foreign body.

Figure 627-2 Vertically oriented linear corneal abrasions secondary to a foreign body underneath the upper eyelid.