Inherited Metabolic Disorders

Barbara K. Burton

Major advances in the recognition and treatment of inborn errors of metabolism have made it more essential than ever that the neonatologist be familiar with the clinical presentation of these disorders. Many of the diseases in this group are associated with symptoms in the neonatal period, and many affected infants find their way into neonatal intensive care units. The likelihood of establishing a diagnosis often is directly related to the level of awareness of the neonatologist responsible for the infant’s care. Although many of the individual inborn errors of metabolism occur infrequently, collectively, they are not rare. There is no doubt that a significant number of children with these disorders are undiagnosed. Every geneticist has had the experience of diagnosing an inborn error of metabolism in a child and discovering that the parents have had one or more other children who died in early infancy of vague or undetermined causes. In such cases, it is reasonable to assume that the other children were similarly affected but undiagnosed. Autopsy findings in such cases are often nonspecific and unrevealing unless special biochemical studies are done. Infection often is suspected as the cause of death, and sepsis is a common accompaniment of inherited metabolic disorders.

The significance of the precise diagnosis of metabolic disease cannot be overemphasized. Increasingly, these disorders are lending themselves to successful medical management. If treatment means the prevention of significant mental retardation or death, even when the numbers are small, the diagnosis is clearly worth pursuing. However, the success of most treatment regimens depends on the earliest possible institution of therapy, stressing the importance of early clinical diagnosis. Even when no effective therapy exists or an infant cannot be salvaged, diagnosis is critical for purposes of genetic counseling.

Inborn errors of metabolism are all genetically transmitted, typically in an autosomal recessive or X-linked recessive fashion, and there is usually a substantial risk of recurrence. Prenatal diagnosis is available for many conditions in this group. Awareness of the diagnosis before birth of an at-risk infant can lead to earlier therapy and an improved prognosis.

This chapter defines the constellation of findings in the newborn that should alert the clinician to the possibility of inherited metabolic disease. The discussion is confined to the disorders for which manifestations are observed in the first few months of life and does not include the many disorders (e.g., most lysosomal storage diseases) that typically present in later infancy or childhood. The laboratory tools used to evaluate infants suspected of having inherited metabolic disease are discussed. Treatment of important groups of metabolic disorders are addressed, focusing on the stabilization and acute management of patients with these conditions.

A list of the major inborn errors of metabolism that have been described clinically in early infancy is shown in Table 41-1. This table cannot be considered complete because it includes only the disorders for which manifestations in the first few months of life have been documented in the literature. It is likely that disorders typically occurring later in childhood occasionally may present as early as the first month of life. New disorders causing neonatal disease undoubtedly will continue to be described. A single literature reference is listed for each disorder in the table, and detailed information about most of the disorders listed can be found in recent editions of reference textbooks 1 (1,2).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM

Acute Metabolic Encephalopathy

Several groups of inherited metabolic disorders, most notably the organic acidemias, urea cycle defects, and certain disorders of amino acid metabolism, typically present with acute life-threatening symptoms in the neonatal period. Because they are associated with protein intolerance, symptoms usually begin after feedings have been instituted.

Affected infants are typically full term and usually appear normal at birth. The interval between birth and clinical symptoms ranges from hours to weeks. The initial findings are usually those of lethargy and poor feeding, as seen in almost any sick infant. Although sepsis is often the first consideration in infants who present in this way, these symptoms in a full-term infant with no specific risk factors strongly suggest a metabolic disorder. Infants with inborn errors of metabolism may rather quickly become debilitated and septic; therefore, it is important that the presence of sepsis not preclude consideration of other possibilities. The lethargy associated with these conditions is an early symptom of a metabolic encephalopathy that may progress to coma. Other signs of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, such as seizures and abnormal muscle tone, may also exist. Evidence of cerebral edema may be observed, and intracranial hemorrhage occasionally occurs (3).

Affected infants are typically full term and usually appear normal at birth. The interval between birth and clinical symptoms ranges from hours to weeks. The initial findings are usually those of lethargy and poor feeding, as seen in almost any sick infant. Although sepsis is often the first consideration in infants who present in this way, these symptoms in a full-term infant with no specific risk factors strongly suggest a metabolic disorder. Infants with inborn errors of metabolism may rather quickly become debilitated and septic; therefore, it is important that the presence of sepsis not preclude consideration of other possibilities. The lethargy associated with these conditions is an early symptom of a metabolic encephalopathy that may progress to coma. Other signs of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, such as seizures and abnormal muscle tone, may also exist. Evidence of cerebral edema may be observed, and intracranial hemorrhage occasionally occurs (3).

TABLE 41-1 INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM THAT PRESENT IN EARLY INFANCY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

An infant with an inborn error of metabolism who presents more abruptly or in whom the lethargy and poor feeding go unnoticed may first come to attention because of

apnea or respiratory distress. The apnea is typically central in origin and a symptom of the metabolic encephalopathy, but tachypnea may be a symptom of an underlying metabolic acidosis, as occurs in the organic acidemias. Infants with urea cycle defects and evolving hyperammonemic coma initially exhibit central hyperventilation, which leads to respiratory alkalosis. Indeed, the finding of respiratory alkalosis in an infant with lethargy is virtually pathognomonic of hyperammonemic encephalopathy.

apnea or respiratory distress. The apnea is typically central in origin and a symptom of the metabolic encephalopathy, but tachypnea may be a symptom of an underlying metabolic acidosis, as occurs in the organic acidemias. Infants with urea cycle defects and evolving hyperammonemic coma initially exhibit central hyperventilation, which leads to respiratory alkalosis. Indeed, the finding of respiratory alkalosis in an infant with lethargy is virtually pathognomonic of hyperammonemic encephalopathy.

TABLE 41-2 LABORATORY STUDIES FOR AN INFANT SUSPECTED OF HAVING AN INBORN ERROR OF METABOLISM | |

|---|---|

|

Vomiting is a striking feature of many of the inborn errors of metabolism associated with protein intolerance, although it is less common in the newborn than in the older infant. If persistent vomiting occurs in the neonatal period, it usually signals significant underlying disease. Inborn errors of metabolism should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is common for an infant to be diagnosed as having a metabolic disorder after having undergone surgery for suspected pyloric stenosis (4). Formula intolerance frequently is suspected, and many affected infants have numerous formula changes before a diagnosis finally is established.

The basic laboratory studies that should be obtained for an infant who has acute life-threatening symptoms consistent with an inborn error of metabolism are listed in Table 41-2.

HYPERAMMONEMIA

Among the most important laboratory findings associated with inborn errors of metabolism presenting with an acute encephalopathy is hyperammonemia. A plasma ammonia level should be obtained for any infant with unexplained vomiting, lethargy, or other evidence of an encephalopathy. Significant hyperammonemia is observed in a limited number of conditions. Inborn errors of metabolism, including urea cycle defects and many of the organic acidemias, are at the top of the list. Also in the differential diagnosis is a condition referred to as transient hyperammonemia of the newborn (THAN) (5). Ammonia levels in these conditions frequently exceed 1,000 μmol/L. The finding of marked hyperammonemia provides an important clue to diagnosis and indicates the need for urgent treatment to reduce the ammonia level. The degree of neurologic impairment and developmental delay subsequently observed in infants with urea cycle defects depends on the duration of the neonatal hyperammonemic coma (6).

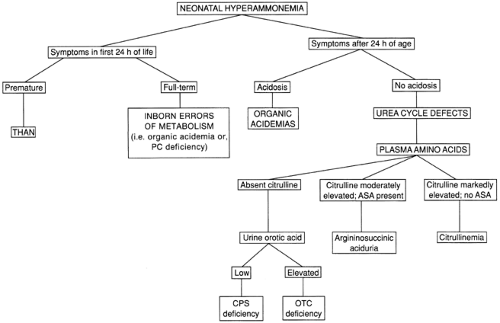

A flow chart for the differentiation of conditions producing significant hyperammonemia in the newborn is shown in Fig. 41-1. The timing of the onset of symptoms may provide an important clue. Infants with urea cycle defects typically do not become symptomatic until after 24 hours of age. Patients with some of the organic acidemias, such as glutaric acidemia type II, or with pyruvate carboxylase deficiency may exhibit symptomatic hyperammonemia during the first 24 hours. Symptoms in the first 24 hours are characteristic of THAN, a condition that is poorly understood but apparently not genetically determined. The typical patient with this disorder is a large premature infant (mean gestational age of 36 weeks) who has symptomatic pulmonary disease, often from birth, and severe hyperammonemia. Survivors do not have recurrent episodes of hyperammonemia and may or may not exhibit neurologic sequelae, depending on the extent of the neonatal insult. There are some affected infants who survive with normal intelligence despite extraordinarily high ammonia levels (5). The disorder has become extremely rare in recent years for unknown reasons.

Infants who develop severe hyperammonemia after 24 hours of age usually have a urea cycle defect or an organic acidemia; infants with organic acidemias typically exhibit a metabolic acidosis and ketonuria as well. Urine organic acids should always be obtained, regardless of whether or not acidosis is present. Metabolic acidosis is not a feature of the urea cycle defects. Plasma amino acid analysis is helpful in the differentiation of the specific defects in this group. Characteristic amino acid abnormalities provide a definitive diagnosis of citrullinemia and argininosuccinic aciduria. Although no diagnostic amino acid elevations are observed in carbamyl phosphate synthetase deficiency or ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, a low or undetectable level of plasma citrulline is observed in both of these conditions. This finding is helpful in differentiating these two conditions from THAN, in which the plasma citrulline level is normal. However, plasma citrulline is not accurately measured in all laboratories performing amino acid analysis, probably because it is important in few other clinical settings. In clinical situations in which this is a critical diagnostic test, samples should be sent to laboratories with expertise in the differentiation of urea cycle defects. Carbamyl phosphate synthetase deficiency and ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency may be differentiated by measuring urine orotic acid, which is low in the former and elevated in the latter. The pattern of inheritance of the two may also help to differentiate them; ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, an X-linked disorder, rarely produces severe hyperammonemia in a female infant, whereas carbamyl phosphate synthetase deficiency, an autosomal recessive disorder, occurs with equal frequency in the two genders.

Although the clinical and laboratory evaluation outlined should lead to a specific tentative diagnosis for virtually

all patients, liver biopsy may be indicated for enzymatic confirmation of the diagnoses of carbamyl phosphate synthetase and ornithine transcarbamylase deficiencies, because these diagnoses dictate rigid lifelong therapy or consideration of hepatic transplantation. Acute treatment should be based on the presumptive diagnosis, with biopsy considered only after the infant is stabilized.

all patients, liver biopsy may be indicated for enzymatic confirmation of the diagnoses of carbamyl phosphate synthetase and ornithine transcarbamylase deficiencies, because these diagnoses dictate rigid lifelong therapy or consideration of hepatic transplantation. Acute treatment should be based on the presumptive diagnosis, with biopsy considered only after the infant is stabilized.

Less significant elevations of plasma ammonia than those associated with inborn errors of metabolism and THAN can be observed in a variety of other conditions associated with liver dysfunction, including sepsis, generalized herpes simplex infection, and perinatal asphyxia. Liver function studies should be obtained in evaluating the significance of moderate elevations of plasma ammonia. However, even in cases of severe hepatic necrosis, it is rare for ammonia levels to exceed 500 μmol/L (7). Mild transient hyperammonemia with ammonia levels as high as twice normal is relatively common in the newborn, especially in the premature infant, and is usually asymptomatic. It appears to be of no clinical significance, and there are no long-term neurologic sequelae (8).

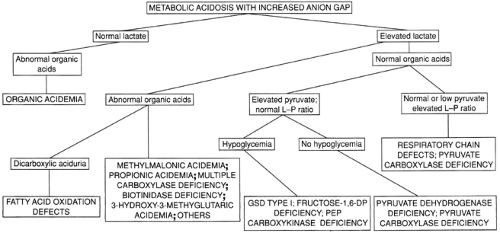

METABOLIC ACIDOSIS

The second important laboratory feature of many of the inborn errors of metabolism during acute episodes of illness is metabolic acidosis with an increased anion gap, readily demonstrable by measurement of arterial blood gases or serum electrolytes and bicarbonate. A flow chart for the evaluation of infants with this finding is shown in Fig. 41-2. An increased anion gap (greater than 16) is observed in many inborn errors of metabolism and in most other conditions producing metabolic acidosis in the neonate. The differential diagnosis of metabolic acidosis with a normal anion gap essentially is limited to two conditions, diarrhea and renal tubular acidosis. Among the inborn errors, the largest group typically associated with overwhelming metabolic acidosis in infancy is the group of organic acidemias, including methylmalonic acidemia, propionic acidemia, and isovaleric acidemia. The list of disorders in this group has expanded dramatically as new disorders have been defined through the use of organic acid analysis.

In addition to specific organic acid intermediates, plasma lactate often is elevated in organic acidemias as a result of secondary interference with coenzyme A (CoA) metabolism. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia commonly are observed and further underscore the clinical similarity of these disorders to neonatal sepsis. Hyperammonemia, sometimes as dramatic as that associated with urea cycle defects, is seen commonly but not uniformly in critically ill neonates with organic acidemias.

The metabolic acidosis associated with organic acidemias and certain other inborn errors of metabolism may have

significant adverse impact on many different organ systems, which may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a wide variety of seemingly unrelated disorders. I had the experience of caring for an infant with isovaleric acidemia who presented at 10 days of age with respiratory distress, severe metabolic acidosis, a dilated heart, and poor cardiac output. The infant was suspected of having the hypoplastic left heart syndrome or other severe congenital heart disease. Cardiac catheterization was performed, even though members of the nursing staff had observed that the infant had a strong unpleasant odor, reminiscent of sweaty feet. Personnel in the catheterization laboratory also noticed that the blood had a strong peculiar odor, but it was not until 18 hours later, long after significant heart disease had been ruled out, that the diagnosis of metabolic disease was first considered. Despite attempts at therapy with dialysis and other measures, the child succumbed to the disease. In this case, the metabolic acidosis led to poor function of the myocardium and not the reverse.

significant adverse impact on many different organ systems, which may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a wide variety of seemingly unrelated disorders. I had the experience of caring for an infant with isovaleric acidemia who presented at 10 days of age with respiratory distress, severe metabolic acidosis, a dilated heart, and poor cardiac output. The infant was suspected of having the hypoplastic left heart syndrome or other severe congenital heart disease. Cardiac catheterization was performed, even though members of the nursing staff had observed that the infant had a strong unpleasant odor, reminiscent of sweaty feet. Personnel in the catheterization laboratory also noticed that the blood had a strong peculiar odor, but it was not until 18 hours later, long after significant heart disease had been ruled out, that the diagnosis of metabolic disease was first considered. Despite attempts at therapy with dialysis and other measures, the child succumbed to the disease. In this case, the metabolic acidosis led to poor function of the myocardium and not the reverse.

Figure 41-2 Evaluating metabolic acidosis in the young infant. fructose-1,6-DP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase; GSD, glycogen storage disease; L/P, lactate/pyruvate. |

Another child subsequently found to have methylmalonic acidemia was admitted through the emergency room with severe metabolic acidosis and a tight, distended abdomen with evidence of multiple air-fluid levels on X-ray films. The history revealed that the child had fed poorly since birth and had repeated episodes of vomiting despite several formula changes. Intestinal obstruction was suspected, and the child was taken to the operating room, in which most of the small intestine was found to be infarcted, presumably secondary to the acidosis and poor tissue perfusion. No anatomic abnormalities were found. Postoperatively, metabolic disease was considered, and the diagnosis of a vitamin B12-responsive form of methylmalonic acidemia was made. The infant died of complications of the disease even though the early diagnosis and treatment of this disorder, before the terminal episode, should have been associated with a good prognosis.

Defects in pyruvate metabolism or in the respiratory chain may lead to primary lactic acidosis presenting as severe metabolic acidosis in infancy (9,10). Unlike most of the other conditions presenting acutely in the newborn, the clinical features of these disorders are unrelated to protein intake. Disorders in this group should be considered in patients with lactic acidosis who have normal or nondiagnostic urine organic acids. Differentiation of the various disorders in this group can be facilitated by measuring plasma pyruvate and calculating the lactate/pyruvate ratio. A normal ratio (less than 25) suggests a defect in pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) or in gluconeogenesis, and an elevated ratio (greater than 25) suggests pyruvate carboxylase deficiency or a mitochondrial respiratory chain defect.

Not all infants with life-threatening metabolic disease have metabolic acidosis or hyperammonemia. For example, patients with nonketotic hyperglycinemia typically present in the neonatal period with evidence of severe and progressive CNS dysfunction, but do not exhibit metabolic acidosis or hyperammonemia (11). Even patients with galactosemia rarely may present with symptoms of acute CNS toxicity, which may progress to cerebral edema, when galactose-1-phosphate levels rise precipitously. Therefore, a series of laboratory studies designed to screen for inborn errors of metabolism should be obtained for any infant with clinical findings suggesting an inborn error of metabolism, even if metabolic acidosis and hyperammonemia are not present. These studies are listed in Table 41-2. Most are self-explanatory. Although not available in many hospital laboratories, amino acid and organic acid analysis can be obtained in any part of the country through reference

laboratories or through referral of samples to medical center genetics units. It is important to insist that any reference laboratory used for this purpose provide prompt test results and reference ranges and provide interpretation of abnormal results.

laboratories or through referral of samples to medical center genetics units. It is important to insist that any reference laboratory used for this purpose provide prompt test results and reference ranges and provide interpretation of abnormal results.

TABLE 41-3 DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH NONGLUCOSE REDUCING SUBSTANCES IN URINE | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Urine testing for reducing substances should be performed using Benedict reagent (Clinitest tablets, Miles, Elkhart, IN). If the result is positive, the urine should be tested for glucose by dipstick. A nonglucose reducing substance in the urine is probably galactose, but there are other possibilities (Table 41-3).

Several disorders associated with an acute metabolic encephalopathy in the neonate deserve special mention because they typically are not associated with hyperammonemia or metabolic acidosis. One of these is nonketotic hyperglycinemia, a condition that typically results in severe and progressive CNS dysfunction, including obtundation, seizures, and altered muscle tone. Routine laboratory studies all yield normal findings. The first diagnostic clue is usually the finding of elevated glycine on plasma amino acid analysis. The diagnosis is confirmed by measurement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) glycine and demonstration of an elevated CSF to plasma glycine ratio. Although therapy of infants with nonketotic hyperglycinemia has been attempted with dietary protein restriction, sodium benzoate, and a variety of other drugs, the results have been disappointing. Most infants with this disorder die or exhibit significant neurologic impairment.

TABLE 41-4 MAJOR INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM PRESENTING IN THE NEONATE AS AN ACUTE ENCEPHALOPATHY | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

A second disorder that produces a progressive en-cephalopathy with no clues on routine laboratory studies is molybdenum cofactor deficiency. The neurologic findings in the affected infant are virtually indistinguishable from those associated with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Surviving infants exhibit similar neurologic sequelae including cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and seizures. The diagnosis may be suggested by the finding of hypouricemia or, beyond the neonatal period, by ectopia lentis noted on ophthalmologic examination. If it is suspected, urine should be screened for the presence of sulfites, a finding attributable to a deficiency of the enzyme sulfite oxidase, which accompanies the disorder.

The inborn errors of metabolism most likely to be associated with an acute encephalopathy in the newborn are summarized in Table 41-4. The typical laboratory findings in each condition or group of conditions also are listed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree