Ingestion of Foreign Bodies

Esophageal Foreign Bodies

Foreign body (FB) ingestions are a common occurrence in infants and young children. The exact incidence is unknown since many cases are not reported. In 2010, the Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers noted over 116,000 cases of FB ingestion. More than 86,000 occurred in children ≤5 years of age.1 The vast majority of ingestions in children are accidental.2 The most common type of FB varies by geographic region. In the USA and Europe, coins are the most common.2,3 Other commonly ingested objects include toys, batteries, needles, straight pins, safety pins (Fig. 11-1), screws, earrings, pencils, erasers, glass, fish and chicken bones, and meat. However, in areas of the world where fish contributes a significant portion of the diet, such as in Asia, a fish bone may be the most common FB ingested in children.2,4

FIGURE 11-1 This child accidentally ingested this open safety pin which was able to be extracted with esophagoscopy.

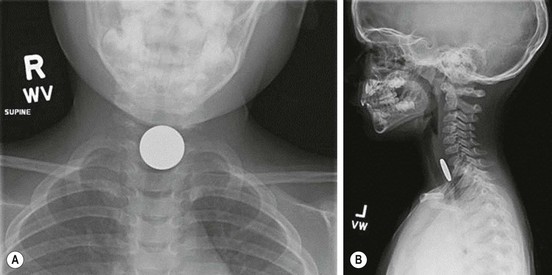

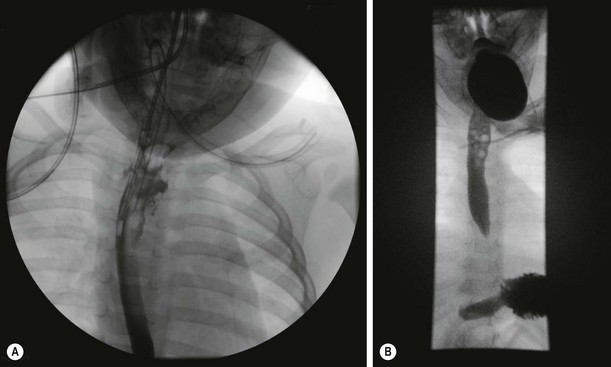

Symptoms of esophageal FB impaction are nonspecific and include drooling, poor feeding, neck and throat pain, vomiting, or wheezing. Radiopaque objects can be detected on the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral neck and chest radiographs (Fig. 11-2), while radiolucent objects may require further workup with a gastrografin esophagram or esophagoscopy depending on the symptoms and level of suspicion (Fig. 11-3).

FIGURE 11-2 This 3-year-old child presented with dysphagia and drooling. (A) The anteroposterior radiograph shows a coin that appears en face in the upper esophagus. (B) The lateral view shows that the coin is posterior to the trachea, confirming its esophageal location.

FIGURE 11-3 A piece of chicken became lodged in this child’s upper esophagus. The chest radiograph was normal, but the esophagram shows the foreign material (arrow) obstructing the esophagus.

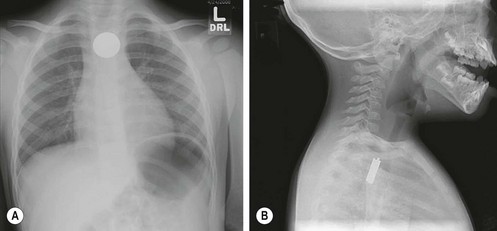

The most common round, smooth object ingested that is amenable to extraction or advancement techniques is a coin. The majority of esophageal coins will appear en face in the anteroposterior view, and from the side on the lateral radiograph (see Fig. 11-2). On occasion, more than one coin will have been ingested (Fig. 11-4).

FIGURE 11-4 This infant was seen in the emergency department for swallowing difficulty and drooling. (A) Anteroposterior radiograph shows a coin in the upper esophagus. (B) However, on the lateral view, there are actually four coins superimposed on one another. The lateral view is very helpful for the purpose of determining whether more than one coin has been ingested.

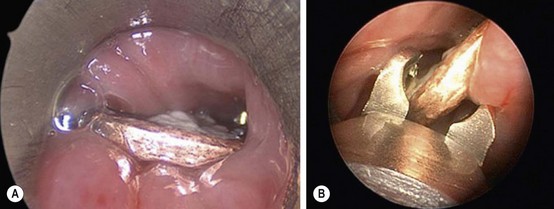

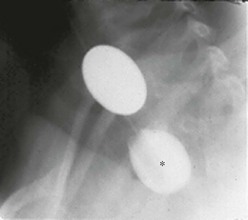

The location of the object on the radiograph is important in determining the treatment options. Approximately 60–70% of FB impactions are located in the proximal esophagus at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter or thoracic inlet.5–7 The majority of FB impactions found in the upper or mid-esophagus will remain entrapped and require retrieval. Options for retrieval include nonemergent endoscopy (rigid or flexible) (Fig. 11-5) and Foley balloon extraction with fluoroscopy (Fig. 11-6). The Foley balloon extraction technique should be limited to round, smooth objects that have been impacted for less than one week in appropriately selected children without any evidence of complications.8 This technique has been shown to have a success rate of 80% while significantly lowering costs. Objects that are impacted in the lower esophagus often spontaneously pass into the stomach. For this reason, certain lower esophageal impactions may be observed for a brief duration of time, or attempted to be advanced into the stomach with bougienage or a nasogastric tube in the emergency department without anesthesia.9 Rarely, a chronic esophageal coin can cause esophageal perforation, but this will usually be contained (Fig. 11-7).

FIGURE 11-5 This coin was lodged in the esophagus of a 2-year-old child. It was unclear how long the coin had been in the esophagus. Rigid esophagoscopy was performed. (A) The coin is seen through the esophagoscope. (B) The optical graspers are being used to grasp the coin and remove it. The safety and success rate for rigid esophagoscopy and coin removal approaches 100% with minimal complications. This is usually a safe and successful way to remove a coin in the esophagus of children in whom the Foley catheter technique is not appropriate.

FIGURE 11-6 This radiograph shows the Foley catheter technique for removing a coin lodged in the upper esophagus. Under fluoroscopy, the Foley catheter is advanced past the coin and the balloon is filled with barium (asterisk). Under fluoroscopy, the catheter is then removed, bringing the coin with it. Care must be taken to ensure the patient does not aspirate the coin during its removal. This is a very cost-efficient way to remove coins in the upper esophagus in young children.

FIGURE 11-7 (A) This child was found to have an esophageal leak after uneventful extraction of a coin. (B) As the leak appeared to be contained, the patient was managed conservatively, and a repeat study two weeks later showed no evidence of a leak. A central line was placed for total parenteral nutrition.

Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies

FB ingestions that are found to be distal to the esophagus are usually asymptomatic when discovered. Signs and symptoms including significant abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fevers, abdominal distention, or peritonitis should alert the provider to potential complications including obstruction and/or perforation. The majority of FBs that pass into the stomach will usually pass through the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully. These patients can be managed as an outpatient. Occasionally, a FB will remain present in the bowel after a period of observation and serial radiographs (Fig. 11-8). Prokinetic agents and cathartics have not been found to improve gut transit time and passage of the FB.10 Often parents are instructed to strain the child’s stool; however, in up to 50% of cases, the FB is not identified even with successful passage.5,11 If the child remains asymptomatic and the FB has not been identified, a repeat abdominal radiograph can be performed at two to three week intervals. Subsequent endoscopy is usually deferred for four to six weeks. Rarely, a chronic esophageal coin can cause esophageal perforation, but this will usually be contained (Fig. 11-8).

FIGURE 11-8 This child began to complain of abdominal pain and the (A) plain film was obtained. Due to the fact that it was unclear how long ago the sewing needle was ingested and because she was exhibiting new symptoms, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. (B) At laparoscopy, the sewing needle was seen to have penetrated the proximal jejunum and (C) was able to be extracted. A water soluble contrast study was performed a few days later. The study was unremarkable, her diet was advanced, and she recovered uneventfully.

Special Topic Ingestions

Batteries

Battery ingestions deserve special attention due to the potential for significant morbidity associated with esophageal battery impactions. Button batteries are more commonly ingested than cylindrical batteries in young children.12 Symptoms occur in less than 10% of cases.12 Button batteries will appear as a round, smooth object on radiographs and are often misdiagnosed as coins. However, on close inspection, some larger button batteries will demonstrate a double contour rim (Fig. 11-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree