20.2 Infective diarrhoea and inflammatory bowel disease

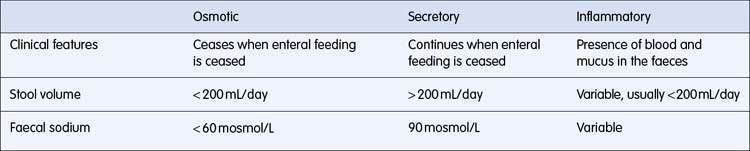

The basic pathological mechanisms causing diarrhoea include osmotic, secretory and inflammatory processes (Table 20.2.1). Often more than one mechanism occurs simultaneously resulting in diarrhoea.

Chronic diarrhoea is defined as symptoms being present for more than 2–3 weeks. This requires further investigation as several important causes such as inflammatory bowel disease need to be excluded to avoid possible systemic complications and negative effects on the nutritional state of the child. This can also have a significant effect on the nutritional state of a child (see Chapter 20.3).

Acute gastroenteritis

Viral gastroenteritis

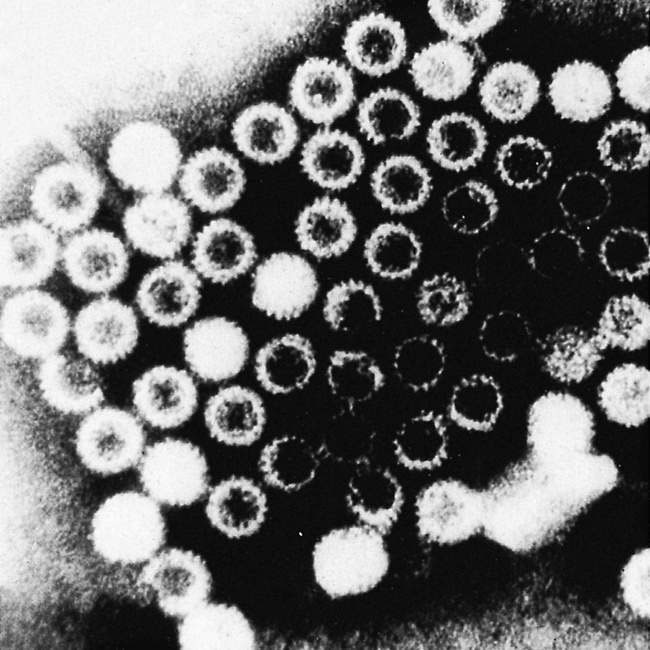

Rotavirus infection (Fig. 20.2.1) is the most common cause of acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide, with a peak incidence between 6 and 24 months of age. It is also a major cause of mortality in developing countries and is responsible for the majority of cases where hospital admission is required. In Australia, before routine infant rotavirus immunization was introduced in 2007, approximately 10 000 children aged under 5 years were hospitalized each year due to rotavirus infection, 115 000 visited a general practitioner, 22 000 required an emergency department visit and, on average, one Australian child died each year from the complications of dehydration and shock. Since 2007, these numbers have fallen dramatically.Infants in developing countries are more susceptible to severe infection causing life-threatening diarrhoea because of pre-existing malnutrition and poor access to primary care. Similarly, Indigenous Australian children require hospitalisation due to rotavirus gastroenteritis about three to five times more commonly than non-Indigenous children.

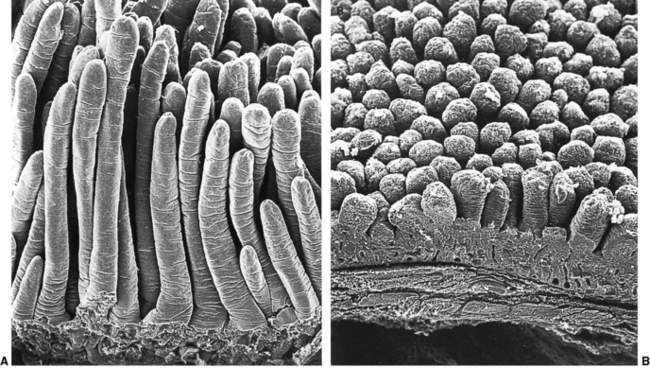

The mucosal damage caused by rotavirus (Fig. 20.2.2) occurs primarily in the small intestine. It results in villus destruction and loss of digestive enzymes found on the tips of villi. This causes impaired digestion of carbohydrates, impaired intestinal absorption of fluid and electrolytes, and fluid loss from the intestine. The need for structural repair places considerable nutritional demands on malnourished children. Repeated asymptomatic reinfection helps maintain immunity.

Clinical features

Acute gastroenteritis is a relatively common cause of presentation to medical attention, but it should remain a diagnosis of exclusion, because several systemic disorders and surgical emergencies can present with diarrhoea and/or vomiting (Box 20.2.1) and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Box 20.2.1 Differential diagnosis of acute diarrhoea and vomiting in infants and children

Dehydration

The signs of dehydration traditionally described are outlined in Box 20.2.2. The three signs that discriminate best between dehydration and adequate hydration are deep breathing, decreased skin turgor and poor peripheral perfusion.