12 Infectious Disease

Infectious Exanthems

Skin and Soft Tissue Findings in Viral Infections

Rubeola (Nine-Day or Red Measles)

Measles is a highly contagious, moderate to severe acute illness with a typical prodrome and mode of evolution. Prodromal symptoms consist of fever, malaise, dry (occasionally croupy) cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis with clear discharge and marked photophobia (Fig. 12-1, A). One to 2 days after onset of prodromal symptoms, a pathognomonic enanthem (Koplik spots) appears on the buccal mucosa (Fig. 12-1, B). The lesions consist of tiny bluish-white dots surrounded by red halos, which increase in number and then fade over a 2- to 3-day period. The exanthem is seen first on day 3 or 4, as the prodromal symptoms and fever peak in severity. It is a blotchy, erythematous, blanching, maculopapular eruption that appears at the hairline and spreads cephalocaudally over 3 days, ultimately involving the palms and soles (Fig. 12-1, C-F). Once generalized, the rash becomes confluent over proximal areas but remains discrete distally. Older lesions tend to develop a rusty hue as a result of capillary leak and cease to blanch with pressure. Fading commences after 3 days, with clearing 2 to 3 days later. Fine, branny desquamation of the most severely involved areas may ensue. Generalized adenopathy may be present in moderate to severe cases.

Rubella (German Measles)

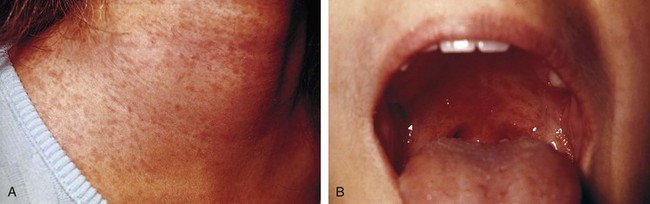

Although rubella has little or no prodrome in children, adolescents, like adults, may experience 1 to 5 days of low-grade fever, mild malaise, adenopathy, headache, sore throat, and coryza. Fever, if present at all in young children, is low grade and rarely lasts more than a day. The exanthem is a discrete, pinkish red, fine maculopapular eruption, which, like measles, typically begins on the face and spreads cephalocaudally (Fig. 12-2, A). The rash becomes generalized within 24 hours, and then begins to fade, clearing completely by 72 hours. Forschheimer spots, an enanthem consisting of small reddish spots on the soft palate, are seen in some patients on day 1 of the rash and can be helpful in the differential diagnosis (Fig. 12-2, B). Adenopathy, often generalized, is a common but not invariable feature. The occipital, posterior cervical, and postauricular nodes tend to be those most prominently enlarged. Arthritis and arthralgias are frequent in adolescent and adult female patients, beginning on day 2 or 3 and typically lasting 5 to 10 days. Large or small joints may be affected.

The incidence of rubella peaks in late winter and early spring, and the disease is contagious in patients from a few days before to a few days after appearance of the exanthem. The incubation period ranges from 14 to 21 days. Complications are rare in childhood and include arthritis, purpura with or without thrombocytopenia, and mild encephalitis. The major complication results from spread of the virus to susceptible pregnant women and their fetuses, resulting in congenital rubella syndrome (see the section, Congenital and Perinatal Infections, later). When such an exposure is thought to have occurred, a specimen of blood should be obtained from the pregnant woman as soon as possible for the measurement of antibody. In addition, an aliquot of serum from this blood draw should be frozen for retesting, if necessary. If the sample obtained at the time of exposure is positive for rubella-specific IgG, then the woman was likely to be immune and not at risk. If it is negative, a second sample should be obtained in 2 to 3 weeks and tested concurrently with the remaining aliquot from the initial sample. If this test is negative, a third sample should be obtained at 6 weeks. If antibody is detected in the second or third specimen, infection has occurred and the fetus is at risk.

Varicella (Chickenpox)

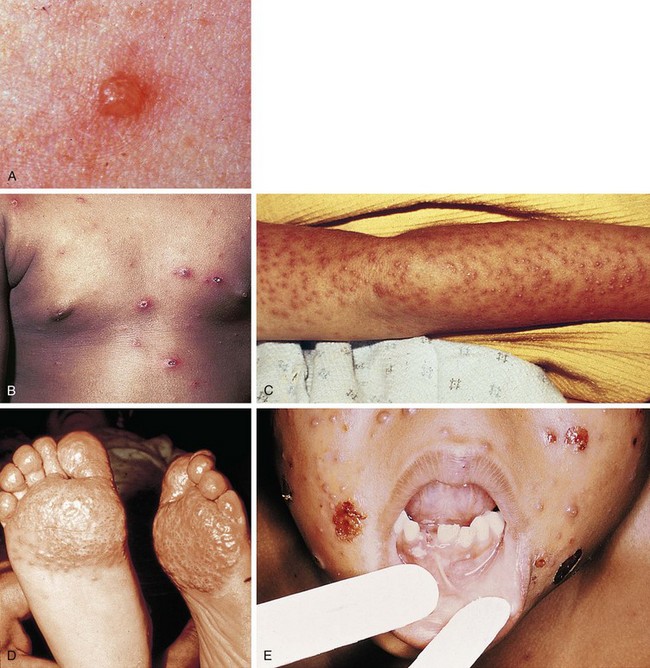

Varicella in the normal pediatric host is a relatively benign, albeit highly contagious illness caused by the varicella-zoster virus. A brief prodrome of low-grade fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, and mild malaise may occur, followed rapidly by the appearance of a pruritic exanthem. Lesions appear in crops and evolve rapidly over several hours. Most patients have three crops, although some may have only one and others may have as many as five. Initial crops involve the trunk and scalp, and subsequent crops are distributed more peripherally; thus the mode of spread is centrifugal. The presence of scalp lesions with the initial crop is often helpful in diagnosing the infection in a patient who presents early in the course of the disease. Lesions begin as tiny erythematous papules that rapidly enlarge to form thin-walled, superficial central vesicles surrounded by red halos (Fig. 12-3, A). Vesicular fluid changes promptly from clear to cloudy; then drying begins, resulting in an umbilicated appearance. As the surrounding erythema fades, a central crust or scab is formed, which sloughs after several days. A hallmark of this exanthem is the finding of lesions in all stages of evolution within a relatively small geographic area of skin (Fig. 12-3, B). In general, all scabs have sloughed by 10 to 14 days. Scarring usually does not occur unless lesions become secondarily infected. It is important to recognize that in patients with preexisting dermatologic problems, the lesions of varicella, like other viral exanthems, tend to appear first and cluster most heavily at sites of prior skin irritation, such as the diaper area or sites of eczematoid dermatitis (Fig. 12-3, C and D).

An enanthem is commonly seen and consists of thin-walled vesicles that rapidly rupture to form shallow ulcers (Fig. 12-3, E). Other mucosal surfaces may be affected as well. Although skin lesions are pruritic, those on the oral, rectal, or vaginal mucosa and those involving the external auditory canal or tympanic membrane can be painful, necessitating analgesia. Systemic symptoms are generally mild, although low-grade to moderate fever may be present during the first few days. In most cases pruritus is the child’s major complaint. In adolescents and adults the illness is more likely to be severe with prominent systemic symptoms and more extensive exanthematous involvement.

Varicella occurs year-round, with peak incidences in late autumn and late winter through early spring. The period of communicability begins 1 to 2 days before the appearance of lesions and lasts until all lesions have crusted over. The incubation period ranges from 10 to 20 days, with high secondary attack rates in susceptible people. The most common complication in normal hosts is secondary bacterial infection of excoriated skin lesions. Such infection can range from impetigo to cellulitis. Group A β-streptococcal superinfection of varicella lesions can be particularly severe, leading to myositis, sepsis, and purpura fulminans (Fig. 12-4, A). Other complications, although rare, include pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. The onset of these complications is typically heralded by a secondary fever spike concurrent with increase in general systemic symptoms. In patients with encephalitis, an altered level of consciousness along with other signs of neurologic dysfunction occurs. Reye syndrome, an encephalopathy of unclear etiology, is a well-recognized but fortunately rare complication that can occur as a child is recovering from acute varicella. Repetitive pernicious vomiting is followed by an altered level of consciousness in which periods of lethargy alternate with periods of delirium or combativeness.

In the immunocompromised host with deficient cellular immunity, varicella is a severe and often fatal disease with CNS, pulmonary, and generalized visceral involvement. Skin lesions are often hemorrhagic and tend to remain vesicular for a prolonged period of time (Fig. 12-4, B and C). With potentially immunocompromised children who have not had varicella previously (including those on short-course, high-dose steroids), parents must be forewarned of these dangers and instructed to notify their physician immediately of any possible exposure. This enables the administration of varicella immune globulin product within 96 hours of exposure, thus reducing the severity of illness. If immune globulin is unavailable, some experts recommend prophylaxis with acyclovir starting on day 7 postexposure for high-risk patients.

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

The varicella-zoster virus, like other herpesviruses, takes up permanent, albeit generally quiescent, residence in its host after initial infection (i.e., varicella). In general, the virus lies dormant in the genome of sensory nerve root cells, but it can reactivate on occasion. Mechanical and thermal trauma, infection, and debilitation all have been postulated as triggers. Immunosuppression can also predispose to reactivation. In the reactivated form, herpes zoster, lesions consist of grouped, thin-walled vesicles on an erythematous base, which are distributed along the course of a spinal or cranial sensory nerve root (Fig. 12-5). They evolve from macule to papule to vesicle and then to a crusted stage over a few days. Hyperesthesia or nerve root pain may precede, accompany, or follow the eruption and does not correlate with the severity of the rash. Pain, if present at all in pediatric patients, is rarely severe and is generally short-lived, unless a cranial nerve dermatome is involved, in which case pain can be excruciating. Fever and constitutional symptoms may or may not be part of the picture, but regional adenopathy is common.

Thoracic dermatomes are involved in most patients, followed in frequency by cervical, trigeminal, lumbar, and facial nerve regions. Cranial nerve involvement may produce a puzzling prodrome consisting of severe headache, facial pain, or auricular pain with no evident cause and lasting up to several days before appearance of the eruption. Lesions appear unilaterally on the tonsillar pillars and uvula with involvement of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve; on the buccal mucosa and palate with involvement of the mandibular division; and on the face, cornea, and tip of the nose with involvement of the ophthalmic branch (Fig. 12-5, D; and see Chapter 20, Fig. 20-45). When the geniculate ganglion is affected, vesicles are seen in the external auditory canal in concert with facial paralysis. Although varicella can be transmitted by patients with herpes zoster, contagion is generally less of a problem because most patients have lesions on areas that are covered by clothing and the oropharynx is not involved in most cases.

Adenovirus Infections

More than 40 distinct types of adenoviruses are capable of producing a variety of clinical illnesses including conjunctivitis, upper respiratory tract infections and pharyngitis, croup, bronchitis, bronchiolitis and pneumonia (occasionally fulminant), gastroenteritis, myocarditis, nephritis, cystitis, and encephalitis. An exanthem occasionally accompanies other symptoms, and a variety of rashes have been described. The eruption may consist of discrete, nonspecific, blanching, maculopapular lesions or it may be morbilliform, rubelliform, or, on occasion, petechial. Typically the rash is generalized when first noted. The most readily identifiable clinical constellation consists of conjunctivitis, rhinitis, pharyngitis with or without exudate, and a discrete, blanching, maculopapular rash (Fig. 12-6). Anterior cervical and preauricular lymphadenopathy, low-grade fever, and malaise are common associated findings. The peak season for adenovirus infections in temperate climates is late winter through early summer, and the infection is maximally contagious during the first few days of illness. The incubation period ranges from 6 to 9 days.

Coxsackie Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease

Of the enteroviruses, coxsackievirus group A16 produces the most distinctive exanthem, known as hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Patients may have a brief prodrome consisting of low-grade fever, malaise, sore mouth, and anorexia, during which lesions are absent. Within 1 to 2 days, oral lesions and soon skin lesions appear. The former usually consist of shallow, yellow ulcers surrounded by red halos. They are found on the labial and buccal mucosal surfaces, the gingivae, tongue, soft palate, uvula, and anterior tonsillar pillars (Fig. 12-7, A and B). Early in the illness, small vesicles may be seen on the palate or mucosal surfaces. These enanthematous lesions usually are only mildly painful. The cutaneous lesions begin as erythematous macules on the palmar aspect of the hands and fingers, the plantar surface of the feet and toes, and the interdigital surfaces. On occasion, the buttocks may be involved as well. They evolve rapidly to form small, thick-walled, gray vesicles on an erythematous base (Fig. 12-7, C-E), which may feel like slivers, be pruritic, or be asymptomatic. More than 90% of patients with disease caused by coxsackievirus A16 have oral lesions, and about two thirds have the exanthem. In those cases in which the cutaneous manifestations are absent, the process is called herpangina (caused by coxsackieviruses and other enteroviruses) and may resemble early herpes gingivostomatitis. However, coxsackievirus ulcers are less painful and are less often associated with the high fever and intense gingival erythema, edema, and bleeding typical of herpes (see Fig. 12-13).

Erythema Infectiosum (Fifth Disease)

Erythema infectiosum is a mildly contagious illness, caused by parvovirus B19, that principally affects preschool and young school-age children. It occurs year-round, with a peak incidence in late winter and early spring. The disorder is characterized primarily by its exanthem. Fever and constitutional symptoms are unusual. On occasion, headache, nausea, myalgias, and peripheral polyarthralgias are reported. The rash begins on the face, with large, bright red, erythematous patches appearing over both cheeks (Fig. 12-8, A). These patches are warm but nontender and have circumscribed borders that are usually macular but may be slightly raised. They are easily distinguished from those of cellulitis and erysipelas (see Figs. 12-34, 12-35, and 12-37) by their symmetry and lack of tenderness, and by the absence of high fever and toxicity. The facial lesions begin to fade on the next day, and a symmetrical, macular or slightly raised, lacy, erythematous rash appears on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (Fig. 12-8, B). Over the next day or so, the rash may spread to the flexor surfaces, buttocks, and trunk. Resolution occurs within 3 to 7 days of onset.

(A, Courtesy Robert Hickey, MD, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa; B, from Cohen BA, Lehman C, editors: Dermatlas.org—Dermatology Image Atlas. Johns Hopkins University [website]. Available from: http://www.dermatlas.org)

Roseola Infantum (Exanthem Subitum)

Roseola infantum is a febrile illness that primarily affects children between the ages of 6 and 36 months. The causative agent is human herpesvirus 6. The clinical course begins abruptly with rapid temperature elevation, which occasionally precipitates a febrile seizure. Anorexia and irritability are the major associated symptoms. Examination reveals no source for the fever, which is usually higher than 39°C. Administration of an antipyretic produces only a transient decrease in temperature, which then rises rapidly to its former value. Although most patients do not look toxic, many infants undergo a sepsis workup and lumbar puncture because of the combination of unexplained high fever and marked irritability. Fever and irritability persist for approximately 72 hours, whereupon the fever abruptly subsides. In most cases an erythematous, maculopapular exanthem appears simultaneously with defervescence, but in a small percentage of patients it develops 1 day before or after fever lysis. Lesions are discrete, rose-pink macules or maculopapules that begin on the trunk and then spread rapidly to the extremities, neck, face, and scalp (Fig. 12-9). They may last several hours to a day or two before resolution.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Clinical Features of Mononucleosis

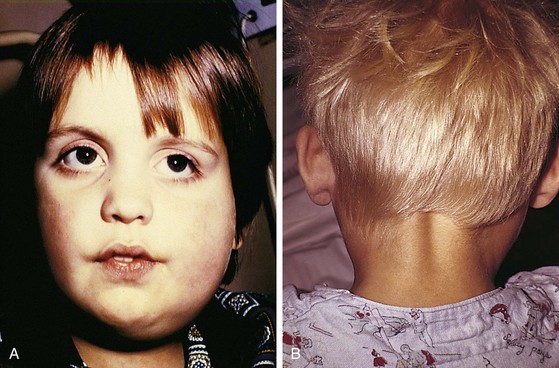

The illness often begins with a prodrome, which lasts from 3 to 5 days, consisting of fatigue, malaise, and anorexia, often in association with headache, sweats, and chills. Photophobia and edema of the eyelids and periorbital tissues may be noted in some patients (Fig. 12-10, A). The acute phase is usually heralded by a fever, which may show wide daily fluctuations. Pharyngitis and cervical node enlargement then become apparent. The sore throat tends to increase in severity over several days before abating and may be associated with significant dysphagia. Tonsillar and adenoidal enlargement can range from mild to marked, and the tonsillar surface may vary in appearance from one of mild erythema to one of severe exudative inflammation with palatal and uvular edema (Fig. 12-10, B). Halitosis and palatal petechiae are common. Approximately one third of patients show severe pharyngeal manifestations. The anterior cervical lymph nodes are routinely enlarged, and posterior cervical adenopathy is characteristic. In classic cases the adenopathy becomes generalized toward the end of the first week. Involved nodes are firm, discrete, and mildly to moderately tender. Splenomegaly develops in approximately 50% of patients in the second to third week of illness; 10% have associated hepatic enlargement.

An exanthem is seen in 5% to 10% of patients with mononucleosis, although this percentage is greatly increased in patients treated with ampicillin or amoxicillin for pharyngeal or respiratory symptoms. Usually an erythematous maculopapular rubelliform rash, the exanthem can be morbilliform, scarlatiniform, urticarial, hemorrhagic, or even nodular (Fig. 12-10, C and D).

Mumps (Epidemic Parotitis)

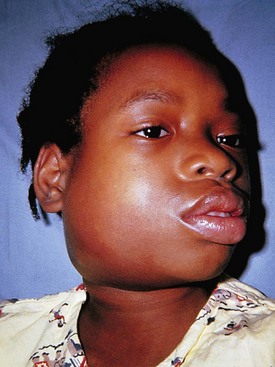

Prodromal symptoms consist of fever, headache, malaise, and anorexia. In the typical case these symptoms are followed within 24 hours by the onset of an earache or face pain, which older children can often localize to the region of the pinna. Pain is aggravated by chewing and by stimulation of salivation (in particular, by sour foods). Parotid swelling generally becomes noticeable within the next 24 hours, increases gradually over the ensuing few days, and then abates over a similar period of time. Fever may persist for the duration of swelling but can disappear early in the course. On examination, an area of tender, indurated swelling, extending from the preauricular area through the subauricular space to the postauricular region, can be palpated (Fig. 12-11, A). With pronounced enlargement the pinna is pushed up and out (Fig. 12-11, B). The gland is indurated and mildly to moderately tender to palpation. The color of the overlying skin is normal. Intraoral examination may reveal erythema and edema of the Stensen duct. Bilateral involvement is usual, although one gland tends to enlarge before the other, and up to 25% of symptomatic patients have unilateral inflammation.

Preauricular swelling and induration, the Stensen duct abnormality, and the absence of prominent overlying erythema help to distinguish parotid swelling from cervical adenitis involving the tonsillar node. In confusing cases and in cases in which the submental or sublingual salivary glands are involved, closely simulating adenopathy, the patient can be given lemon juice to sip or a lemon wedge to suck. In patients with mumps, this results in a prompt enlargement of the affected gland and in pain as salivation is stimulated, whereas no such change is seen in patients with adenopathy. In cases of bacterial parotitis, the patient is likely to have high fever and show signs of toxicity. The overlying skin is erythematous, with exquisite tenderness found on palpation (Fig. 12-12). Purulent drainage from the Stensen duct can often be seen when the gland is massaged.

Herpes Simplex Infections

The herpes simplex viruses produce infections that primarily involve the skin and mucous membranes, although in neonates, immunocompromised hosts, and, rarely, normal hosts, infection can result in disseminated disease and CNS involvement. Like other herpesviruses, herpes simplex virus—after producing initial (primary) infection—enters a latent or dormant stage, residing in local sensory ganglia; once latent, the virus can be reactivated at any time, causing recurrent infection. The two distinct serotypes of herpes simplex virus are types 1 and 2. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is the more common pathogen and can produce a variety of clinical syndromes. In contrast, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is usually a genital pathogen (see Chapter 18), although occasionally it is the source of oral lesions and is the usual agent associated with neonatal herpes (see the section, Congenital and Perinatal Infections, later).

Diagnosis of symptomatic HSV infections can often be made on clinical grounds alone, particularly in cases of primary infection. When the diagnosis is in question, a Giemsa-stained (Tzanck) smear of scrapings obtained from the base of a vesicle (see Chapter 8) usually demonstrates ballooned epithelial cells with intranuclear inclusions and multinucleated giant cells when the lesion is herpetic. Rapid antigen detection tests are more specific and sensitive than Tzanck smears. Viral cultures, obtained by unroofing a lesion and swabbing its base, yield results in 24 to 72 hours. Acute and convalescent titers are less useful and are of no help during recurrences.

Primary Herpes Simplex Infections

More than 90% of primary infections caused by HSV-1 are subclinical; nevertheless, because the virus is ubiquitous, symptomatic primary infections are common. One of the most prevalent forms of primary infection is herpetic gingivostomatitis. Patients with this condition typically have high fever, irritability, anorexia, and mouth pain; infants and toddlers often drool copiously. The gingivae become intensely erythematous, edematous, and friable and tend to bleed easily. Small, yellow ulcerations with red halos are seen routinely on the buccal and labial mucosa, on the gingivae and tongue, and often on the palate and tonsillar pillars (Fig. 12-13, A and B). Within a short time, yellowish-white debris builds up on mucosal surfaces and halitosis becomes prominent. Thick-walled vesiculopustular lesions may also develop on the perioral skin (Fig. 12-13, C). The anterior cervical and tonsillar nodes are enlarged and tender. Symptoms last from 5 to 14 days, but the virus may be shed for weeks after resolution. The illness can vary from mild to marked in severity. Young children with prolonged high fever and intense pain may become dehydrated and ketotic and should be monitored closely and hydrated as needed. The diffuseness of the ulcerations and mucosal inflammation and the intense gingivitis help to distinguish this disorder from herpangina (see Fig. 12-7) and exudative tonsillitis, as well as from other forms of gingivitis.

Although the virus can infect any area of the skin, the lips and fingers or thumbs (as in herpetic whitlow) are the most common sites of involvement (Figs. 12-13 and 12-14). On occasion, the eyelids and periorbital tissues are affected (Fig. 12-15); this can lead to keratoconjunctivitis, which is diagnosed on the basis of finding characteristic dendritic ulcerations on slit-lamp examination (see Chapter 19). Because this complication carries a risk of causing permanent visual impairment, urgent ophthalmologic consultation is indicated whenever there is any suspicion of ocular herpetic infection.

Eczema Herpeticum (Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption)

Patients with atopic eczema and other forms of chronic dermatitis are at risk for a particularly severe form of primary HSV infection and thus should avoid contact with people with active herpetic infections. Parents who have a history of recurrent herpes and a child with eczema should be instructed to be meticulous about hand washing during periods of reactivation. The illness is heralded by the onset of high fever, irritability, and discomfort. Lesions appear in crops and primarily involve areas of currently or recently affected skin. Typically they evolve to form pustules, which rupture and form crusts over the course of a few days. On occasion, these lesions become hemorrhagic (Fig. 12-16). Multiple crops can appear over 7 to 10 days, simulating varicella. However, the slower evolution of lesions, the tendency of such lesions to become hemorrhagic, their concentration in eczematoid areas, and the persistence of fever and systemic symptoms for as long as 1 week help to distinguish this disorder from varicella. Severity ranges from mild to fulminant and depends in part on the extent of the preceding dermatitis. When the area of involvement is large, fluid losses can be severe and potentially fatal. Accordingly, prompt treatment with intravenous acyclovir is recommended. A significant risk of secondary bacterial infection also exists.

Recurrent Herpes Simplex Infection

As mentioned earlier, after primary infection, HSV becomes latent within the ganglia that lie in the region of initial involvement; reactivation of the latent virus results in localized recurrences at or near the site of previous infection. Fever, sunlight, local trauma, menses, and emotional stress are recognized triggers, and because the mouth is the major site of primary infection, labial and perioral lesions (cold sores) are seen most commonly. Many patients report a prodrome of localized burning along with stinging or itching before the eruption of grouped vesicles. These vesicles contain yellow, serous fluid and often appear smaller and less thick-walled than primary lesions (Fig. 12-17). After 2 to 3 days the vesicular fluid becomes cloudy, and then crusts form. Although fever and systemic symptoms are absent, regional nodes may be enlarged and tender. The localization of the lesions to a small area helps to distinguish them from those of herpes zoster. Prodromal symptoms and discomfort help to distinguish recurrent HSV infection from impetigo and contact dermatitis.

Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome

A mild prodrome consisting of low-grade fever and malaise is typical and may be associated with generalized adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly (especially with hepatitis B), upper respiratory tract symptoms, and diarrhea. Within a few days the first of several crops of lesions appears abruptly. The lesions consist of discrete, firm, lichenoid papules with flat tops (Fig. 12-18, A and B) and range from 1 to 10 mm in diameter, tending to be larger in infants and smaller in older children. Papules can be flesh colored, pink, red, dusky, coppery, or purpuric. They are distributed fairly symmetrically over the extremities (including the palms and soles), buttocks, and face, with relative sparing of the trunk and scalp (Fig. 12-18, B), although the upper back may be involved. They tend to remain discrete but can become confluent, especially over pressure points (Fig. 12-18, C), and the Koebner phenomenon may be seen. Pruritus is unusual, and there is no associated mucosal enanthem.

Treatment is symptomatic. Steroid creams are contraindicated because they may make the rash worse.

Skin and Soft Tissue Findings in Bacterial Infections

Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus) (Formerly Called Streptococcal Scarlet Fever)

Once a severe illness associated with high morbidity and mortality, scarlet fever has become a much milder illness over the past several decades. In classic cases, now seen less than 10% of the time, the patient experiences the abrupt onset of fever, chills, malaise, headache, sore throat, and vomiting; abdominal pain also may be a prominent complaint. Within 12 to 48 hours an exanthem appears and rapidly generalizes, usually beginning on the trunk and spreading peripherally, but sometimes spreading cephalocaudally. The face is flushed with perioral pallor (Fig. 12-19, A). The remaining skin becomes diffusely erythematous and is covered by tiny pinhead-sized papules, giving the sunburn appearance of erythroderma. The texture is sandpapery on palpation, and the erythema blanches with pressure (Fig. 12-19, B). The skin may be pruritic, but it is not tender. In severe cases, vesicles may form. After generalization the rash becomes accentuated in skin folds and creases, and 1 to 3 days after its appearance, petechiae may appear in a linear distribution along the creases, forming Pastia lines (Fig. 12-19, C). Examination of the oropharynx in classic cases reveals large, erythematous and exudative tonsils, along with palatal erythema and petechiae (see Chapter 23). The uvula may be erythematous and edematous as well. The tongue also shows characteristic findings. During the first 2 days it has a white coating through which erythematous papillae project (a “white” strawberry tongue) (Fig. 12-19, D). Subsequently the white coat peels, leaving a glistening red surface with prominent papillae (a “red” strawberry tongue) (Fig. 12-19, E). Tender cervical adenopathy is noted in 30% to 60% of patients. Without treatment, the rash, fever, and pharyngitis resolve within 1 week; with treatment, improvement is relatively rapid. Desquamation occurs regardless of treatment and begins several days after onset, progressing cephalocaudally (Fig. 12-19, F and G). The skin is shed in fine, thin flakes (in contrast to the thick flakes that characterize desquamation after staphylococcal exanthems) (Fig. 12-20; and see Fig. 12-22), and the extent of this process is directly proportional to the intensity of the exanthem.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree