KEY POINTS

• Bacterial and viral infections are common in pregnancy with the potential for severe consequences due to the physiologic changes of pregnancy.

• Treatment regimens for pregnant women must take into account the physiologic changes of pregnancy, the risks to the fetus, and optimal maternal health.

• Women should be screened for common infections during pregnancy and receive appropriate preventive treatment based on the specific organisms identified.

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Urinary tract infections are frequently encountered medical complications of pregnancy.

• The three types of urinary tract infection in pregnancy are

• Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB)

• Cystitis

• Pyelonephritis

• The uropathogens most commonly isolated in ASB are similar to those in cystitis and pyelonephritis. Escherichia coli is the primary pathogen in 65% to 80% of cases. Other pathogens include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter species, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and group B β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Background

Definition

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as persistent bacterial colonization of the urinary tract without urinary symptomatology.

Epidemiology

• ASB occurs in 2% to 7% of pregnant women.

• The prevalence of ASB in pregnant and nonpregnant women is similar; therefore, pregnancy is not believed to predispose to ASB.

• However, ASB is more likely to become symptomatic and progress to pyelonephritis secondary to the physiologic changes of pregnancy (1). If untreated, 20% to 30% of pregnant women with ASB will develop acute pyelonephritis.

Treatment

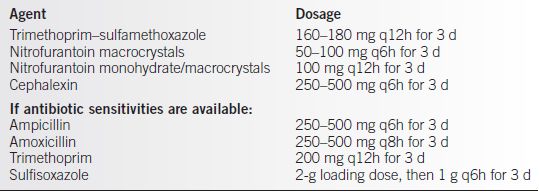

Treatment should be considered when two clean catch specimens are positive for the same bacteria 105 colony-forming units, or a single catheterized specimen is positive for 102 bacteria of the same species (see Table 23-1).

Follow-up

• A negative repeat culture obtained approximately 10 days after completion of therapy is necessary to document successful treatment.

Table 23-1 ACOG Recommended Oral Therapy for ASB or Acute Cystitis

Maternal and Fetal Complications

• Acute pyelonephritis increases maternal risk for sepsis, respiratory insufficiency, anemia, and transient renal dysfunction.

• ASB increases the risks of preterm labor, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

• Therefore, all pregnant women should be screened for ASB early in pregnancy.

Pyelonephritis

• Acute pyelonephritis is most commonly treated with hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics.

• Intravenous therapy is usually continued until the patient is afebrile for 24 to 48 hours and symptomatically improved. The patient can then be changed over to outpatient oral antibiotics to complete a total of 10 days of therapy.

• Recommended antimicrobial regimens include

• Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, 160/800 mg q12h

• Ampicillin, 1 to 2 g q6h, plus gentamicin, 1.5 mg/kg q8h

• Ceftriaxone, 1 to 2 mg q24h

• A third-generation cephalosporin first-line agent

• Suppressive therapy. Women treated for pyelonephritis are placed on antibiotic suppression for the remainder of the pregnancy and periodically screened for recurrence. Choices for suppression are

• Nitrofurantoin, 50 to 100 mg hs or

• Cephalexin, 250 to 500 mg hs

• All other women treated for urinary tract infections should have periodic rescreening for infection with cultures or urine dipstick for nitrates or leukocyte esterase. If infection recurs, patients are treated and then placed on chronic suppression.

PNEUMONIA

Background

Etiology

• Pneumonia is an infection with inflammation involving the parenchyma, distal bronchioles, and alveoli (2).

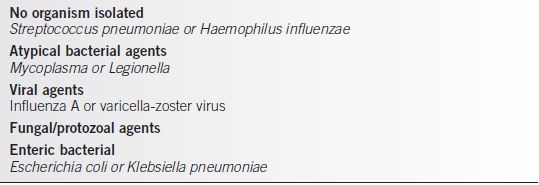

• Approximately two-thirds of cases of pneumonia are bacterial in origin, with two-thirds of those caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. This is followed by Haemophilus influenzae and atypical pathogens such as Mycoplasma and Legionella.

• Two common viral agents are influenza A and varicella, which can be particularly menacing during pregnancy (2).

• Opportunistic infections with fungi and protozoans are especially noted in immunocompromised patients.

Table 23-2 Microbiologic Isolates from Pregnant Patients (Decreasing Frequency of Occurrence)

Epidemiology

Pneumonia occurs in the pregnant population with a frequency equal to that of the general population.

Diagnosis

• Laboratory tests to aid diagnosis of pneumonia include anteroposterior and lateral shielded chest x-ray, sputum Gram stain and culture, blood cultures, and complete blood count with differential.

• In bacterial pneumonia, lobar consolidation is usually observed, with pleural effusion present in about 25% of cases. Leukocytosis may be present. Blood cultures are positive in about one-third of cases.

• In viral pneumonia, the respiratory symptoms may not be impressive initially, but the pregnant patient can rapidly develop respiratory failure. Chest x-ray findings include a unilateral patchy infiltrate (2).

Treatment

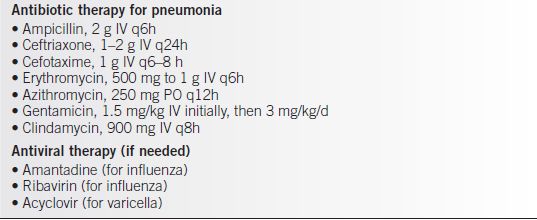

• Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage is recommended. If the patient’s condition worsens, anaerobic and gram-negative coverage can be supplemented.

• Once intravenous therapy is discontinued, oral therapy is continued for a total of 10 to 14 days (Tables 23-2 and 23-3).

Table 23-3 Therapy for Pneumonia

TUBERCULOSIS

Background

• Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading infectious disease in the world. The majority of patients presenting with TB have pulmonary disease.

• Progression of TB is not affected by pregnancy.

• There is no evidence to suggest an increased incidence of preterm labor or other adverse pregnancy outcomes in cases of treated TB (3).

Treatment

• The currently recommended initial treatment of drug-susceptible TB disease in pregnancy is

• Isoniazid (INH) and rifampin daily, with the addition of ethambutol initially.

• Pyridoxine (50 mg qd) should always be given with INH in pregnancy because of the increased requirements for this vitamin in pregnant women.

• If drug susceptibility testing of the isolate of M. tuberculosis reveals it to be susceptible to both INH and rifampin, then ethambutol can be discontinued.

• If pyrazinamide is not used in the initial regimen, INH and rifampin must be given for 9 months instead of 6 months.

• The treatment of any form of drug-resistant TB during pregnancy is extraordinarily difficult and should be handled by an expert with experience with the disease (2).

• The treatment of asymptomatic TB (positive PPD) should be delayed until after delivery unless there is evidence of recent infection.

• Because the risk of INH hepatitis is increased in the postpartum period, patients must be monitored closely for hepatotoxicity.

Complications for the Fetus

• Congenital infection of the infant also can occur via aspiration or ingestion of infected amniotic fluid. If a caseous lesion in the placenta ruptures directly into the amniotic cavity, the fetus can ingest or inhale the bacilli. Inhalation or ingestion of infected amniotic fluid is the most likely cause of congenital TB if the infant has multiple primary foci in the lung, gut, or middle ear.

• The mortality rate of congenital TB has been close to 50%, primarily because of failure to suspect the correct diagnosis.

CHORIOAMNIONITIS AND ENDOMYOMETRITIS

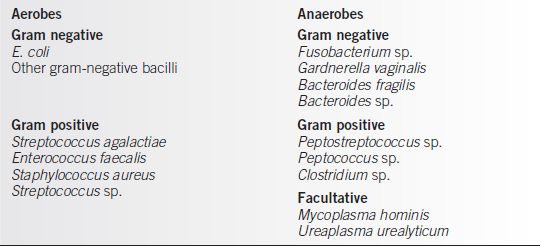

• In an uncomplicated pregnancy, there is no change in vaginal flora except for a progressive increase in colonization by Lactobacillus.

• A pregnancy complicated by bacterial vaginosis, preterm labor, or premature rupture of membranes predisposes the woman to chorioamnionitis.

• Postpartum, there are dramatic changes in the makeup of vaginal flora. There is a marked increase in the number of anaerobic species by the third postpartum day. Predisposing factors to anaerobic colonization include trauma, lochia, suture material, and multiple intrapartum vaginal examinations (4,5).

Chorioamnionitis

Background

Chorioamnionitis is an infection that involves the amniotic cavity and the chorioamniotic membranes. Microscopically, bacteria and leukocytes are noted between the amnion and the chorion.

Pathogens

Chorioamnionitis is most commonly the result of ascending contamination of the uterine cavity and its contents by the lower genital tract flora, although systemic infections can infect the uterus via blood (Table 23-4).

Table 23-4 Chorioamnionitis Organisms

Risk Factors

Risk facts for intra-amniotic infection include ruptured membranes before labor, labor duration, preterm labor, internal fetal monitoring, cervical examinations during labor, nulliparity, young age, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, cervical colonization (e.g., with gonorrhea or group B Streptococcus [GBS]), and bacterial vaginosis.

Diagnosis

• The diagnosis is made by clinical examination, based on maternal and fetal manifestations of intrauterine infection.

• Maternal manifestations include fever, tachycardia, uterine tenderness, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, and maternal leukocytosis (unreliable).

• Fetal manifestations include tachycardia and possibly a non–reassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

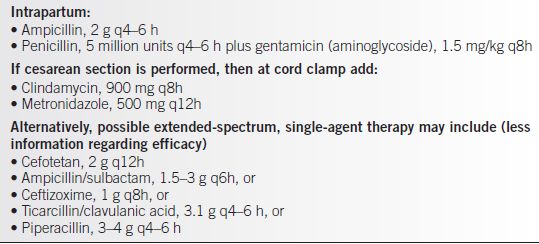

Treatment

• Intravenous antibiotics should be initiated immediately on diagnosis.

• Prompt intrapartum administration of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (Table 23-5) results in better maternal and fetal outcomes than when therapy is delayed until after delivery.

Table 23-5 Chorioamnionitis: ACOG Recommendations Intravenous Therapy

Complications for the Mother and Fetus

• The average interval between diagnosis of chorioamnionitis and delivery is from 3 to 7 hours.

• There has never been a defined “critical time interval” after which maternal and neonatal complications increase. Recent studies have indicated that longer diagnosis-to-delivery times do not correlate with worsening prognosis of either mother or newborn.

• Because there is little evidence that cesarean delivery offers an advantage over vaginal delivery, route-of-delivery decisions should be based on standard obstetric indications (5).

GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS

Background

• GBS is a leading cause of neonatal bacterial sepsis in the United States (6). Incidence has been decreasing after the release of revised disease prevention guidelines in 2002.

• Streptococcus agalactiae is a gram-positive coccus that colonizes the lower gastrointestinal tract of approximately 10% to 30% of all pregnant women in the United States. Secondary spread to the genitourinary tract commonly ensues.

• Colonization of the genitourinary tract creates the risk for vertical transmission during labor or delivery, which may result in invasive infection in the newborn during the first week of life. This is known as early-onset GBS infection and constitutes approximately 80% of GBS disease in newborns.

• Invasive GBS disease in the newborn is characterized primarily by sepsis, pneumonia, or meningitis (7). The incidence of invasive GBS decreased from 0.47/1000 LB in 1999 to 2001 to 0.34/1000 LB in 2003 to 2005 (p < 0.001) (6).

Evaluation

Recommendations for Prophylaxis

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends following a screening-based approach for the prevention of neonatal GBS disease.

Screening-Based Approach

• All pregnant women should be screened by culture at 35 to 37 weeks of gestation for anogenital GBS colonization.

• Patients should be informed of the screening results and of potential benefits and risks of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis for GBS carriers.

• Culture techniques that maximize the likelihood of GBS recovery should be used. Because lower vaginal and rectal cultures are recommended, cultures should not be collected by speculum examination. The optimal method for GBS screening is collection of a single standard culture swab or two separate swabs of the distal vagina rectum. Swabs may be placed in a transport medium if the microbiology laboratory is off-site. The sample should be identified as being specifically for GBS culture.

• Laboratories should report the results to the delivery site and to the physician who ordered the test. GBS prenatal culture results must be available at the time and place of delivery.

Treatment

• Intrapartum chemoprophylaxis should be offered to all pregnant women identified as GBS carriers by culture at 35 to 37 weeks of gestation.

• If the results of GBS culture are not known at the time of labor, intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis should be administered if one of the following risk factors is present:

• Less than 37 weeks of gestation

• Duration of membrane rupture of 18 hours or more

• Temperature of 100.4°F (38.0°C) or more

• Women with GBS bacteriuria in any concentration in the current pregnancy or who previously gave birth to an infant with an early onset of the disease should receive intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis.

• Women with negative vaginal and rectal cultures within 5 weeks of delivery do not require intrapartum antibiotics regardless of gestational age.

• Oral antimicrobial agents should not be used to treat women who are found to be colonized with GBS during prenatal screening. Such treatment is not effective in eliminating carriage or preventing neonatal disease (8).

• Routine intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis for GBS-colonized women undergoing cesarean section deliveries without labor or membrane rupture is not recommended.

Medications

Intrapartum chemoprophylaxis

• For intrapartum chemoprophylaxis, intravenous penicillin G (5 million units initially and then 2.5 million units every 4 hours) should be administered until delivery.

• Intravenous ampicillin (2 g initially and then 1 g every 4 hours until delivery) is an acceptable alternative to penicillin G, but penicillin G is preferred because it has a narrow spectrum and thus is less likely to select for antibiotic-resistant organisms.

• For penicillin-allergic women, clindamycin (900 mg IV q8h until delivery) or erythromycin (500 mg IV q6h until delivery) may be used, although GBS resistance to clindamycin is increasing. (Penicillin G does not need to be administered to women who have a clinical diagnosis of amnionitis and who are receiving other treatment regimens that include agents active against streptococci.) (8)

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

Background

Etiology

Perinatal transmission of HIV accounts for virtually all new HIV infections in children.

Epidemiology

Women presented approximately 20% of the cases of AIDS reported to the CDC through 2003 (9). In the year 2000, an estimated 6000 to 7000 HIV-infected women gave birth, and an estimated 280 to 370 infants were infected in the United States. Of these HIV-infected women, one in eight did not receive prenatal care and one in nine did not have HIV testing before giving birth. The CDC estimates that the number of infants born with HIV each year dropped from 1650 (1991) to fewer than 200 (2004).

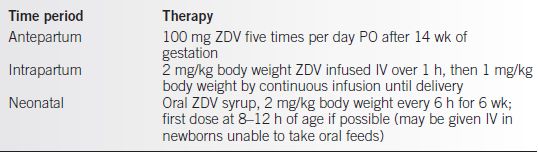

Treatment

Procedures

In 1994, following clinical trials that demonstrated a two-thirds reduction in perinatal HIV transmission with zidovudine (ZDV) therapy for infected pregnant women and their infants, the Public Health Service (PHS) issued guidelines for the use of ZDV during pregnancy. This was followed by recommendations for universal HIV counseling and voluntary testing of pregnant women in July 1995 (10) (Table 23-6).

Table 23-6 Zidovudine Therapy for the Prevention of Perinatal Transmission of HIV

From Dattel BJ. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: beyond AZT (ZDV). Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:645–657.

Risk Factors for Transmission

• Transmission of HIV infection from the mother to child is influenced by many factors.

• Known correlates of HIV-1 transmission include high maternal plasma viremia, advanced clinical HIV disease, reduced maternal immunocompetence, prolonged duration of time after rupture of the amniotic membranes before delivery, vaginal delivery, direct exposure of the fetus to maternal blood during the delivery process, and prematurity or low birth weight of the newborn (11).

• There is no single factor that, by itself, seems to accurately predict whether an individual woman will transmit HIV to her child.

Antiretroviral Therapy

• ZDV monotherapy remains the standard for the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV, but it is not adequate for the treatment of pregnant women infected with HIV.

• Optimal therapy is two nucleoside analog revised transcriptase inhibitors and a protease inhibitor. This regimen has significant beneficial effects on CD4 counts, viral load, and survival in comparison with ZDV monotherapy (12,13).

• These treatment recommendations are based on the following risk for perinatal transmission:

• Twenty percent among 396 women who do not receive antiretroviral drugs

• Ten percent of 710 women taking ZDV alone

• Four percent of 186 women receiving oral antiretroviral drugs

• One percent of these taking three drug combinations

• ZDV alone is no longer a preferred agent for the treatment of HIV in the nonpregnant patient but is considered a first-line agent during pregnancy.

• Nevirapine should not routinely be initiated in treatment-naïve women with CD4 cell carry greater than 250 cells/mm3 because of potential hepatotoxicity and fatal risk.

• Recommended regimens include

• ZDV + lamivudine + lopinavir/ritonavir or atazanavir/ritonavir

• Alternatives include

• Zid + lamivudine + nelfinavir.

• ZDV + lamivudine + nevirapine if CD4 less than 250.

• ZDV + lamivudine + ritonavir-boosted saquinavir on darunavir.

• Alternatively, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI)/nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) with good placental passage (tenofovir, emtricitabine, or abacavir) can be used if ZDV toxicity, such as severe anemia, develops.

• Low CD4 counts of less than 200 cells/mm3 suggest more advanced disease. Women with low counts should receive ZDV and a multiple drug regimen (HAART therapy) (12).

• Data suggest that patients with low viral loads (i.e., less than 2500 copies of HIV RNA per mL) are at lower risk of disease progression than those with high (2500 to 20,000 copies of HIV RNA per mL) or very high (greater than 20,000 copies of HIV RNA per mL) viral loads, indicating a relationship between increasing viral load and vertical transmission from the mother to fetus/infant.

Development of a Treatment Plan

• To develop an appropriate treatment plan, the physician must know the status of the HIV-1–infected pregnant patient’s CD4 count and viral load.

• Intrapartum ZDV therapy is not required if viral load is less than 400.

OTHER VIRAL DISEASES

Influenza

Background

Influenza is an acute, communicable infection that occurs primarily in winter months. Because of its high infectivity and frequency of genetic mutation, novel strains of orthomyxovirus influenza, the etiologic agent, often cause major epidemics.

Diagnosis

• Generalized symptoms of headache, fever, myalgia, malaise, cough, and substernal chest pain appear abruptly within 1 to 2 days after infection.

• Physical examination may reveal basilar rales.

• The chest x-ray may show bilateral interstitial infiltrates.

• Gram stains of sputum show insignificant numbers of bacteria and mononuclear cells.

• Identification of the virus within exfoliated epithelial cells after reaction with fluorescent conjugates of an influenza antiserum is the only rapid method of definitive diagnosis.

• The virus can be cultured from nasopharyngeal washings, nasal swabs, and throat swabs.

• Serum antibody is detectable 2 to 3 weeks after infection by hemagglutination inhibition, neutralization, or complement fixation antibody testing. Paired specimens are necessary for the diagnosis.

Prognosis

Influenza generally is a self-limited disease, but serious morbidity and mortality do occur.

Mother

• Pregnant women are a high-risk group during influenza epidemics.

• Increased mortality is caused by viral pneumonia itself and by superimposed staphylococcal and gram-negative enteric pneumonias.

• Rates of spontaneous abortion are as high as 25% to 50%.

Fetus

• Influenza virus can be transmitted transplacentally to the fetus.

• Many studies of large numbers of patients have failed to link influenza and congenital malformations. However, serious maternal illness with hypoxia can cause premature labor and abortion.

Treatment

• Hospitalization of pregnant women is required if febrile or with pulmonary symptoms due to high rates of pneumonia especially in the third trimester.

• Antiviral prophylaxis should be initiated as soon as possible in pregnant women. Studies from 2009 to 2010 influenza season demonstrated less severe disease and fewer deaths.

• Oseltamivir is generally preferred: 75 mg two times per day for 5 days.

• Pregnant women who are seriously ill should be hospitalized.

• Bacterial superinfection should be treated empirically on the basis of presumed pathogens. Nafcillin and either a third-generation cephalosporin or gentamicin would be adequate initial therapy, which can be modified later on the basis of culture results.

• The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive flu vaccine regardless of gestational age.

Measles

Background

Measles (rubella) is a highly contagious, exanthematous, common childhood disease with peak incidence in the spring. Widespread vaccination had reduced the number of cases in the United States. However, worldwide measles remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality making it the fifth most common cause of death in children under 5 years of age (14).

Diagnosis

• Small, irregular, bright red spots (Koplik spots) that are diagnostic of measles appear on buccal and sometimes other mucosal membranes at the end of the 10- to 14-day incubation period.

• Catarrhal symptoms of coryza, cough, keratoconjunctivitis, and fever are prominent early in the illness.

• The maculopapular rash begins on the face and spreads downward to the extremities.

• The rash, which often becomes confluent, fades in the same sequence.

• Patients who are partially immune have milder catarrh, fewer Koplik spots, and a more discreet and fainter rash.

• Measles virus can be identified by immunofluorescent testing in smears from nasal secretions, sputum, and oropharyngeal surfaces and by culture of these specimens.

• Fourfold or greater increases in hemagglutination inhibition, neutralizing, or complement-fixing antibodies can be demonstrated in convalescent serum drawn 2 to 3 weeks after infection.

Prognosis

Mother

• Morbidity from the respiratory symptoms and rash and mortality from the infrequent complications of encephalitis and myocarditis are the same for pregnant and nonpregnant women.

• Spontaneous abortions and premature deliveries are common.

Fetus

• Measles virus penetrates the placenta, and newborns have or develop typical exanthematous lesions.

• Most reports, but not all, indicate no increase in congenital malformations in infants born to infected mothers (15,16).

Treatment

Management

• Supportive measures of bed rest, fluids, antipyretics, expectorants, and steam inhalation reduce morbidity.

• Immune serum γ-globulin (0.5 mL/kg) given within 6 days after exposure minimizes or prevents measles symptomatology.

• Secondary bacterial complications, particularly pneumonia, are treated with appropriate antibiotics.

Prevention

• Pregnant women who are exposed to measles and who are susceptible (i.e., do not have antibody) should receive γ-globulin. Infants born to women with active measles should receive γ-globulin (0.25 mL/kg).

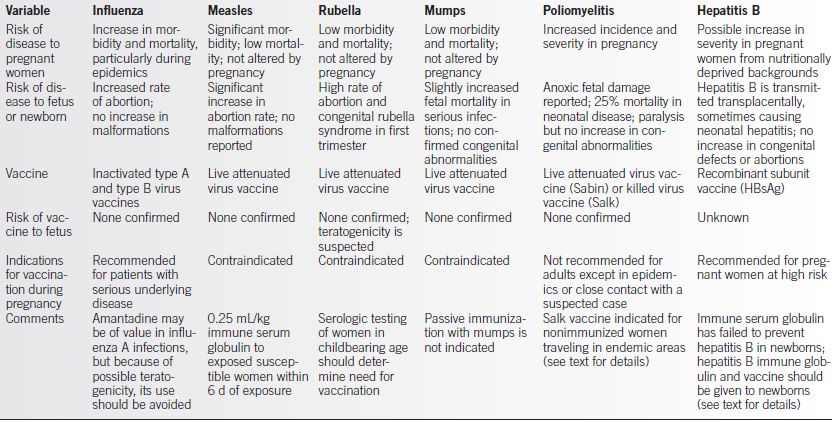

• Women who have not had measles or documented measles immunity should receive two doses of the live virus vaccine, 1 month apart, at least 30 days before becoming pregnant. Vaccine is contraindicated during pregnancy (see Table 23-7).

• Women without documented immunity by history or serology or those patients vaccinated before 1980 should be revaccinated with two doses of the live virus vaccine before becoming pregnant because of waning immunity.

Rubella

Background

• Rubella (German measles) is a highly contagious exanthematous disease of childhood and early adulthood.

• Despite the availability of effective vaccines, up to 20% of women of childbearing age do not possess rubella antibody (17).

Diagnosis

• Fever, cough, conjunctivitis, headache, arthralgias, and myalgias occur after a 14- to 21-day incubation period and a 1- to 5-day prodromal period.

• Postauricular, occipital, and cervical lymphadenopathies are prominent early findings. Arthritis is a frequent occurrence in adult women.

• The maculopapular rash begins on the face, spreads downward, and subsequently fades in the same top-to-bottom order.

• The illness lasts from a few days to 2 weeks.

• Rubella virus can be isolated from pharyngeal secretions, blood, urine, and stools.

Table 23-7 Immunization for Viral Infections During Pregnancy

HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; d, day.

Adapted from Leontic EA, Respiratory disease in pregnancy. Med Clin North Am. 1977;61:111.

• Increases in hemagglutination inhibition, neutralizing, and complement-fixing antibodies are demonstrable 2 to 4 weeks after infection. Most laboratories presently use enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or latex agglutination testing of paired sera to detect recent infection.

Prognosis

Mother

• Morbidity from the rash, respiratory illness, arthritis, and infrequent encephalitis are the same for pregnant and nonpregnant women. Fatality is rare.

• Spontaneous abortion and stillbirth are two to four times more frequent in pregnancies complicated by rubella.

Fetus

• Direct infection of the fetus occurs.

• If the disease is acquired during the first trimester of pregnancy, the risk of fetal malformation or death ranges from 10% to 34%.

• Acquisition of infection later in pregnancy results in fewer and usually less deleterious fetal abnormalities.

• Manifestations of congenital rubella include cataracts, blindness, cardiac anomalies (patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, pulmonary valve stenosis), deafness, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, violaceous birthmarks, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia, lymphadenopathy, encephalitis, and cleft palate (18).

Treatment

Management

• Supportive measures of bed rest, fluids, and acetaminophen for treatment of headache and arthritis usually suffice for this mild, self-limited illness.

• Therapeutic abortion should be considered except in instances in which infection is known to occur in the third trimester of pregnancy. During 2001–2004, the median number reported was 13. Since 2001, only five infants with congenital rubella have been reported.

• Epidemiologic evidence suggests rubella is no longer endemic in the United States.

Prevention

• Prepubertal and nonpregnant postpubertal women without documented antirubella antibodies should be immunized with live attenuated rubella vaccine.

• Women who are vaccinated should not become pregnant for 3 months after vaccination.

• Neither accidental immunization of a pregnant woman nor exposure to virus shed by recently immunized children has resulted in fetal infection (see Table 23-7).

• Rubella vaccine exposure in pregnancy is not an indication for termination.

Mumps

Background

Mumps is a contagious disease of children and young adults (18).

Diagnosis

• Fever, myalgia, malaise, and headache of variable severity occur after a 2- to 3-week incubation period.

• Parotitis is the most prominent feature, and this finding establishes the diagnosis.

• Mastitis and oophoritis can occur in postpubertal women.

• The demonstration of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody by immunofluorescent techniques or a fourfold or greater increase in serum complement-fixing antibody confirms the diagnosis.

Prognosis

Mother

• The morbidity from parotitis and the complications of mastitis, oophoritis, and encephalitis are the same for pregnant and nonpregnant women.

• Spontaneous abortions are more frequent in women who are infected during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Fetus. There has been a growing controversy concerning the development of congenital endocardial fibroelastosis (19).

Treatment

Management

• Administer symptomatic treatment to relieve the discomfort of fever and parotitis.

• Passive immunization with hyperimmune mumps immunoglobulin is no longer recommended because the drug is not of value.

Prevention

Vaccination with live attenuated mumps virus is suggested for nonpregnant postpubertal women who have not had mumps parotitis (see Table 23-7).

Poliomyelitis

Background

Poliomyelitis, currently a rare illness in pregnancy, was, in the prevaccine era, more common and more severe in pregnant than in nonpregnant women of similar age (20). This increase in incidence was attributed to hormonal changes in pregnancy and to greater exposure to young children.

Diagnosis

• Fever, headache, coryza, nausea, vomiting, and sore throat precede the characteristic paralytic phase, which is marked by hyperesthesia, muscle pain, and flaccid paralysis.

• Poliovirus can be isolated from feces, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

• Increases in neutralizing and complement-fixing antibodies are demonstrable in serum obtained at 2 and 4 weeks after infection.

Prognosis

Mother

• In the prevaccine era, morbidity and mortality were higher in the pregnant than in the nonpregnant state.

• The incidence of abortion is increased.

Fetus

• There is no increase in the incidence of congenital abnormalities with intrauterine infection.

• Paralysis and growth retardation occur in infants infected in utero. Neonatal poliomyelitis has a mortality of approximately 25%.

Treatment

Management

• Isolation procedures are required for infected mothers and newborns to prevent spread of the infection through excretory products.

• Supportive care to prevent deformities and, if necessary, to maintain adequate maternal ventilation is indicated during the acute illness.

Prevention

• If immediate protection against poliomyelitis is needed because of travel to an endemic area, a single dose of oral vaccine is given unless time permits the schedule required for the inactivated vaccine (see Table 23-7).

• The inactivated vaccine is recommended for booster injections because the live attenuated oral vaccine has, on rare occasions, caused poliomyelitis in adults.

COXSACKIE VIRUSES

Background

Coxsackie virus serotypes A and B cause a wide spectrum of brief, self-limited illnesses involving one or more organ systems (20).

Diagnosis

• Herpangina, lymphonodular pharyngitis, and rhinopharyngitis indistinguishable from rhinovirus-induced common colds occur in pregnant women infected with coxsackievirus A. Aseptic meningitis is caused by both serotypes. Pleurodynia is caused by infections with coxsackievirus B.

• Coxsackievirus can be isolated from pharyngeal secretions and feces, but for practical purposes, culture is rarely performed.

• Because of the large numbers of serotypes, serologic proof of infection—demonstration of fourfold or greater increases in neutralizing or complement-fixing antibody—is impractical except in epidemics.

Prognosis

Mother

• The coxsackievirus-induced illnesses are self-limited and are not associated with significant maternal mortality.

• The incidence of abortion is not increased.

Fetus

• Coxsackievirus A infections are of no consequence to the fetus.

• Coxsackievirus B infections cause serious illness (myocarditis and encephalitis) and fetal mortality in the perinatal period. The most common defect associated with coxsackievirus B infection is tetralogy of Fallot, but definitive evidence linking this or other congenital abnormality to coxsackievirus B infections is lacking.

Treatment

Management

• Symptomatic treatment is indicated for the mother, and supportive treatment is indicated for the fetus with myocarditis or encephalitis.

• Newborns who survive infection usually do not have residual defects.

Prevention

No vaccine is available.

Varicella (Chickenpox)-Zoster

Background

• Varicella is a common childhood illness caused by the varicella-zoster herpes virus that is characterized by cutaneous vesicles that crust and scab. It is transmitted by droplets or by direct contact with an infected person and is highly contagious to susceptible persons after household exposure.

• Most cases occur in children so that 95% of adults show serologic evidence of immunity (21).

• The mean incubation period of varicella is 15 days, with a range of 10 to 21 days.

• Infectivity occurs from 2 days before the onset of skin lesions until 5 days after the lesions have crusted.

• Childhood varicella usually is uncomplicated, and although varicella is uncommon in adults, adulthood varicella carries increased risks of death from pneumonia.

Diagnosis

• Before the onset of rash, a 1- to 2-day prodromal period of fever, headache, malaise, and anorexia may occur. Prodromal symptoms increase with age.

• Characteristic skin lesions appear on the trunk, scalp, face, and extremities. In a normal host, rash progresses in stages over a 1-week period: maculae, papule, vesicle, pustule, and crusted lesion.

• If present, fever lasts 1 to 3 days. All organ systems may be involved.

• Pneumonia and hepatitis are the primary serious complications.

Treatment

Healthy Woman Presenting for Preconceptional Counseling or First Prenatal Visit

• If a woman has a positive history of chickenpox, she is considered immune; therefore, a question about a history of chickenpox should be included during preconceptional counseling and at the initial prenatal visit.

• Women with a negative or equivocal history should have a serum varicella titer drawn to determine their immune status (varicella IgG).

• Also, because the vaccine may not be as immunogenic as past natural infection, patients who have been vaccinated should have serologic testing for varicella titers.

• Because the vaccine consists of a modified live virus, nonimmune women who are not pregnant can receive the vaccine but should avoid pregnancy for 1 month thereafter.

• Nonimmune pregnant women should receive the vaccine postpartum; the vaccine is not contraindicated with breast-feeding (22)

• There is no risk for pregnant women of acquiring varicella from children with recent varicella vaccination.

A Nonimmune Pregnant Woman Exposed to Chickenpox

• A person with chickenpox is infectious from 2 days before the appearance of typical lesions until 5 days after the vesicles crust over.

• It is important to note that 85% of adults who do not recall having had chickenpox nevertheless have protective antibody levels.

• In a potentially exposed patient, determining her varicella titer first is preferable to administering varicella-zoster immunoglobulin (VZIG), because VZIG is relatively expensive (~$400 for the usual adult dose) and because it is not stocked in local pharmacies. The patient’s serum must be collected within 10 days of the earliest exposure because only by then can it be determined if the antibody detected is an indication of protection from prior exposure versus antibody response to the current exposure.

• VZIG must be administered within 96 hours of exposure, and it provides no benefit when administered after the onset of symptoms. VZIG reduces the rates of clinical varicella in exposed persons, but it has not been shown to prevent adverse fetal effects; therefore, VZIG’s only purpose is to prevent or reduce the severity of illness in the mother (22).

A Pregnant Woman with Chickenpox

• All patients with suspected varicella infection should be isolated and evaluated with only varicella-immune medical staff in attendance.

• The diagnosis is usually clinical. Fever, malaise, and the characteristic rash appear 10 to 21 days after exposure.

• The care is isolated palliation.

• The most dangerous maternal complication is varicella pneumonia. When varicella pneumonia develops in pregnant women, the morbidity and mortality are comparatively high. Supportive oxygen and ventilator therapy should be used as indicated. There is general agreement that intravenous antiviral therapy should be given to pregnant women with any respiratory embarrassment associated with chickenpox.

• Antiviral therapy consists of inhibitors of herpes DNA polymerase (acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir). There are insufficient data regarding the risk/benefit ratio of giving these antivirals to pregnant varicella patients without pulmonary symptoms (22).

Chickenpox in the Immediate Peripartum Period

• When maternal chickenpox breaks out close to the time of delivery, the mother may infect the baby before there has been adequate time for her to produce and transfer protective antibodies across the placenta. These newborns suffer high morbidity and mortality rates.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree