Imperforate Anus and Cloacal Malformations

‘Imperforate anus’ has been a well-known condition since antiquity.1–3 For many centuries, physicians, as well as individuals who practiced medicine, have tried to help these children by creating an orifice in the perineum. Many patients survived, most likely because they suffered from a type of defect that is now recognized as ‘low.’ Those with a ‘high’ defect did not survive. In 1835, Amussat was the first to suture the rectal wall to the skin edges which was the first actual anoplasty.2 Stephens made a significant contribution by performing the first anatomic studies in human specimens. In 1953, he proposed an initial sacral approach followed by an abdominoperineal operation, if needed.4 The purpose of the sacral stage of this procedure was to preserve the puborectalis sling, considered a key factor in maintaining fecal incontinence. Over the next 25 years, different surgical techniques were described, with the common denominator being the protection and use of the puborectalis sling.5–8

The posterior sagittal approach for the treatment of imperforate anus was performed first in 1980, and its description was published in 1982.9 With this approach, the unique opportunity arose to correlate the external appearance of the perineum with the operative findings and, subsequently, with the clinical results.

Incidence, Types of Defects, and Terminology

An anorectal malformation occurs in one out of every 4000 to 5000 newborns and is slightly more common in males.10–12 The estimated risk for a couple having a second child with an anorectal malformation is approximately 1%.13–17 The most frequent defect in males is imperforate anus with a rectourethral fistula.18 In females, it is a rectovestibular fistula.18 Imperforate anus without a fistula is a rather unusual defect, occurring in about 5% of the entire group of malformations, and is associated with Down syndrome.18,19 Historically, a cloaca has been considered an unusual defect, whereas a high incidence of rectovaginal fistula has been reported in the literature.20 In retrospect, we now know that a cloaca is the third most common defect in female patients after vestibular and perineal fistulas, whereas a rectovaginal fistula is actually a rare defect, present in less than 1% of all cases.21,22 It is likely that most females with a persistent cloaca were erroneously thought to have a rectovaginal fistula. Many of these patients underwent repair of the rectal component but were left with a persistent urogenital sinus.21,23 Additionally, most rectovestibular fistulas were erroneously called ‘rectovaginal fistula’.21 A rectobladderneck fistula in males is the only true supralevator malformation and occurs in about 10%.18 As it is the only malformation in males in which the rectum is unreachable through a posterior sagittal incision, it requires an abdominal approach (via laparoscopy or a laparotomy) in addition to the perineal approach.

Anorectal malformations represent a wide spectrum of defects. The terms ‘low,’ ‘intermediate,’ and ‘high’ are arbitrary and not useful in current therapeutic or prognostic terminology. A therapeutic and prognostically oriented classification is depicted in Box 35-1.24

Male Anorectal Defects

Rectoperineal Fistulas

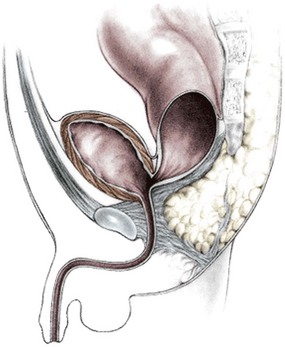

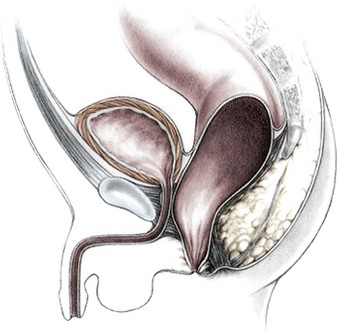

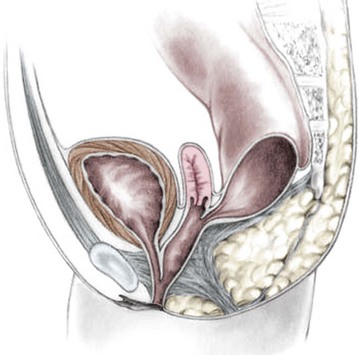

Rectoperineal fistula is the lowest defect. The rectum is located within most of the sphincter mechanism. Only the lowest part of the rectum is anteriorly mislocated (Fig. 35-1). Sometimes, the fistula does not open into the perineum but rather follows a subepithelial midline tract, opening somewhere along the midline perineal raphe, scrotum, or even at the base of the penis (Fig. 35-2). This diagnosis is established by perineal inspection. No further investigations are required. Usually, the anal fistula opening is stenotic. The terms covered anus, anal membrane, anteriorly mislocated anus, and bucket-handle malformations all refer to rectoperineal fistulas.

FIGURE 35-1 This drawing shows the course of a perineal fistula in a male. The rectum is located within most of the muscle complex. Only the most distal aspect of the rectum is misplaced.

Rectourethral Fistulas

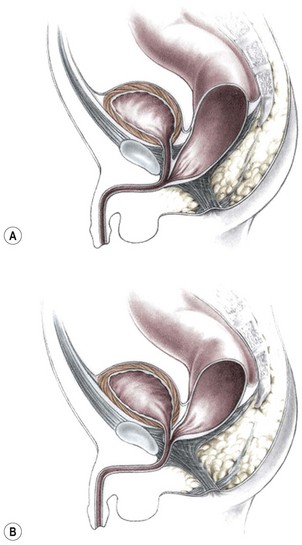

Imperforate anus with a rectourethral fistula is the most common defect in males.18 The fistula may be located at the lower (bulbar) (Fig. 35-3A) or the higher (prostatic) part of the urethra (Fig. 35-3B).

FIGURE 35-3 Anorectal atresia with rectourethral fistulas. (A) Rectourethrobulbar fistula; (B) rectourethroprostatic fistula.

Immediately above the fistula, the rectum and urethra share a common wall. The lower the fistula, the longer is the common wall. This is an important anatomic fact, which guides the operation. The rectum is usually distended and surrounded laterally and posteriorly by the levator muscle. Between the rectum and the perineal skin, a portion of striated voluntary muscle called the muscle complex is present. The contraction of these muscle fibers elevates the skin of the anal dimple. At the level of the skin, a group of voluntary muscle fibers, called parasagittal fibers, are located on both sides of the midline. Lower urethral fistulas are usually associated with good-quality muscles, a well-developed sacrum, a prominent midline groove, and a prominent anal dimple. Higher urethral fistulas are more frequently associated with poor-quality muscles, an abnormally developed sacrum, a flat perineum, a poor midline groove, and a barely visible anal dimple. Of course, exceptions to these rules exist. Occasionally, the infant passes meconium through the urethra, which is an unequivocal sign of a rectourinary fistula.

Rectobladderneck Fistulas

In this defect, the rectum opens into the bladder neck (Fig. 35-4). The patient usually has poor prognosis for bowel control because the levator muscles, the striated muscle complex, and the external sphincter frequently are poorly developed. The sacrum is often deformed and short. In fact, the entire pelvis seems to be underdeveloped. The perineum is often flat, which is evidence of poor muscle development. About 10% of males fall into this category.18

Imperforate Anus without Fistula

Interestingly, most patients with this unusual defect have a well-developed sacrum and good muscles, and have a good prognosis in terms of bowel function.18,19 The rectum usually terminates approximately 2 cm from the perineal skin. Although the rectum and urethra do not communicate, these two structures are separated only by a thin common wall. About half of the patients with no fistula also have Down syndrome, and more than 90% of patients with Down syndrome and imperforate anus have this specific defect, suggesting a chromosomal link.17–19 The fact that these patients have Down syndrome does not seem to interfere with their good prognosis for bowel control.19

Rectal Atresia/Rectal Stenosis

In this unusual defect in male patients (less than 1% of the entire group of malformations), the lumen of the rectum is totally (atresia) or partially (stenosis) interrupted.18 The upper pouch is represented by a dilated rectum, whereas the lower portion empties into a small anal canal that is in the normal location and is 1–2 cm long (Fig. 35-5A). These two rectal structures may be separated by a thin membrane or by dense fibrous tissue. The repair involves a primary anastomosis between the upper pouch and lower anal canal, and is ideally approached posterosagittally with splitting of the anal canal longitudinally (Fig.35-5B). Patients with this defect have all the necessary elements for continence and have an excellent functional prognosis because they have a well-developed anal canal, normal sensation in the anorectum, and normal voluntary sphincters. These patients must be screened for a presacral mass.25

Female Anorectal Defects

Rectoperineal Fistulas

From the therapeutic and prognostic viewpoint, this common defect is equivalent to the perineal fistula described in the male patient.18 The rectum is well positioned within the sphincter mechanism, except for its lower portion, which is anteriorly located. The rectum and vagina are well separated (Fig. 35-6). The key anatomic issues are the anal opening in relation to the sphincter mechanism, and the length of the perineal body.

Rectovestibular Fistulas

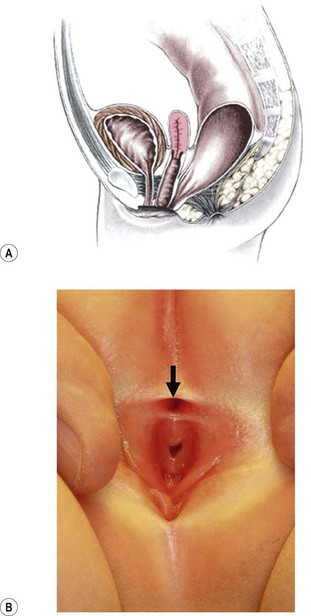

Rectovestibular fistula is the most common defect in females and has an excellent functional prognosis. The diagnosis is based on clinical examination. A meticulous inspection of the newborn’s genitalia allows the clinician to observe a normal urethral meatus and a normal vagina, with a third hole in the vestibule, which is the rectovestibular fistula (Fig. 35-7). About 5% of these patients will have two hemivaginas with a vaginal septum.26

FIGURE 35-7 (A) Schematic drawing of a rectovestibular fistula. (B) Female neonate with a rectovestibular fistula is in the prone position. The rectal fistula (arrow) is located in the posterior aspect of the vestibule.

This defect can be repaired without a protective colostomy by experienced surgeons.27–29 The advantage of this approach is that it avoids the potential morbidity of a colostomy and reduces the number of operations to one from as many as three (colostomy, main repair, and colostomy closure). Many patients do very well with a primary neonatal operation without a protective colostomy. However, a perineal infection followed by dehiscence of the anal anastomosis or perineal body, or recurrence of the fistula provokes severe fibrosis that may interfere with the sphincter function. If these complications occur, the patient may have lost the best opportunity for an optimal functional result because secondary operations do not render the same prognosis as a successful primary operation.30 Thus, a protective colostomy is still the best way to avoid these complications for most surgeons. The decision to perform a colostomy or primary repair in these cases must be made individually by the surgeon based on experience and the clinical condition of the patient. At our institution, neonates without significant associated defects undergo repair without a colostomy.

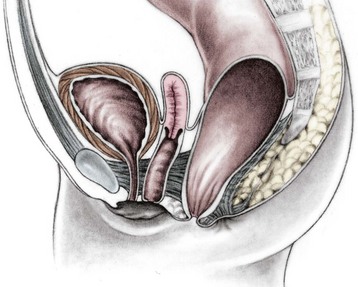

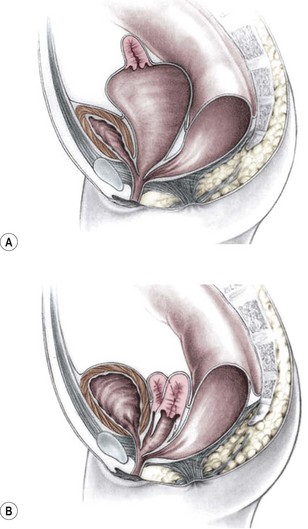

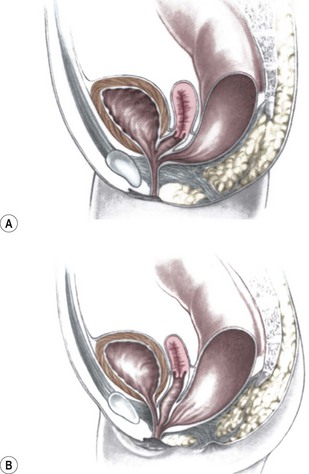

Persistent Cloaca

This group of defects represents the extreme in the spectrum of complexity of female malformations. A cloaca is a defect in which the distal portions of the rectum, vagina, and urinary tract fuse and create a single common perineal channel. The diagnosis of a cloaca is a clinical one. This defect should be suspected in a female born with imperforate anus and small-looking genitalia. Careful separation of the labia discloses a single perineal orifice. The length of the common channel varies from 1–7 cm, and is very important for operative and prognostic implications (Fig. 35-8). A common channel of less than 3 cm usually means that the defect can be repaired with a posterior sagittal operation without opening the abdomen. Common channels longer than 3 cm are more complex, mobilization of the vagina is often difficult, and some form of vaginal replacement may be needed during the definitive repair. When the rectum opens high into the dome of the vagina (Fig. 35-9), an abdominal approach must be utilized to mobilize the bowel.

FIGURE 35-8 (A) Schematic diagram of a long common channel in a female with a cloacal anomaly. (B) The more commonly encountered short common channel cloaca is depicted.

FIGURE 35-9 A schematic diagram of the rectum inserting high into the posterior vagina with a short common urethral and vaginal channel is shown.

Frequently, the vagina is abnormally distended and full of secretions (hydrocolpos) (Fig. 35-10A). The distended vagina compresses the trigone and interferes with drainage of the ureters, and is frequently associated with hydronephrosis. This condition may be diagnosed prenatally.31,32 The dilated vagina can also become infected (pyocolpos) and may lead to perforation and peritonitis. Such a large vagina may represent a technical advantage for the repair as there is more vaginal tissue to facilitate the reconstruction. A frequent finding in cloacal malformations is the presence of different degrees of vaginal and uterine septation or duplication (Fig. 35-10B). In these cases, the rectum usually enters between the two hemivaginas. Rarely, patients have cervical atresia. During puberty, a variety of anatomic anomalies may mean that they are unable to drain menstrual blood through the vagina, can accumulate menstrual blood in the peritoneal cavity, and sometimes require emergency operations.26,33 An evaluation of the patient’s Müllerian anatomy, either at the time of the definitive repair or at colostomy closure, is very important and can prevent future problems.26 Short common channel cloacal malformations (<3 cm) are usually associated with a well-developed sacrum, a normal-appearing perineum, and adequate muscles and nerves. Therefore, a good functional prognosis can be expected.

Associated Defects

Sacrum and Spine

Sacral deformities are the most frequently associated defect.34 One or several sacral vertebrae may be missing. A single missing vertebrae does not seem to have important prognostic implications.18 However, more than two absent sacral vertebrae represent a poor prognostic sign in terms of bowel continence and, sometimes, urinary control, and is consistent with caudal regression. A hemisacrum is usually associated with a presacral mass and poor bowel control.25 Other sacral abnormalities, such as spinal hemivertebra, have negative implications for bowel control.

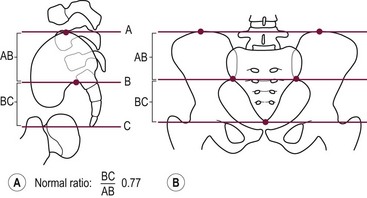

A sacral ratio is an objective evaluation of the sacrum (Fig. 35-11). The sacral ratio can range from 0.0 to 1.0. The normal sacral ratio in children is 0.77. Children with anorectal malformations suffer varying degrees of poor sacral development. We have never seen a patient have bowel control with a sacral ratio of less than 0.3. Greater than 0.7 is usually associated with good bowel control.

FIGURE 35-11 Drawings with landmarks necessary for the calculation of the sacral ratio. (A) Lateral view. (B) Anteroposterior view. The normal ratio is 0.77.

A tethered cord is frequently associated with anorectal malformations, and its presence has been assumed to be associated with a poor functional prognosis.35–44 Although it is true that most of these children have a poor prognosis, the presence of a tethered cord is usually found in patients with a very high defect, very abnormal sacrum, or spina bifida. Therefore, it is difficult to know whether the tethered cord itself is responsible for the poor prognosis. Although it is unclear whether the operation to release the tethered cord changes the functional bowel prognosis of the patient, it does seem to improve urinary function and certainly avoids motor and sensory deterioration of the lower extremeties.41,44

The reported frequency of associated genitourinary defects varies from 20–54%.45–57 The accuracy and thoroughness of the urologic evaluation may account for the reported variation.

It is clear that the higher the malformation, the more frequent are the associated urologic abnormalities. Patients with persistent cloacas or rectobladderneck fistulas have a 90% chance of having an associated genitourinary abnormality.51 Conversely, children with low defects such as perineal fistulas have less than a 10% chance of having an associated urologic defect. Hydronephrosis, urosepsis, and metabolic acidosis from poor renal function represent the main sources of morbidity. Thus, a thorough urologic investigation is particularly important in patients with high defects. The evaluation in every child with imperforate anus must include an ultrasound (US) of the kidneys and abdomen to evaluate for the presence of hydronephrosis or any other urologic obstructive process. In patients with a cloaca, this study is especially important to exclude the presence of hydrocolpos. Further urologic investigations after this initial screening may also be necessary.

Newborn Management

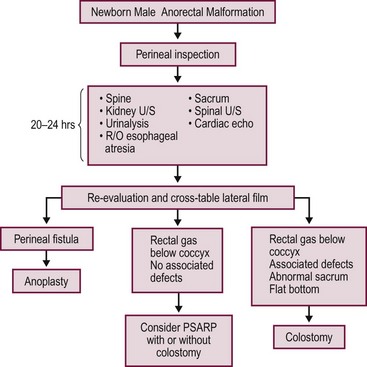

A decision-making algorithm for the initial management in male infants is seen in Figure 35-12.

FIGURE 35-12 Algorithm for the management of male newborns with anorectal malformations based on the physical examination and radiographs. PSARP, posterior sagittal anorectoplasty; U/S, ultrasonography; R/O, rule out.

Radiographic evaluations may not show the correct anatomy before 24 hours because the rectum is collapsed. It takes a significant amount of intraluminal pressure to overcome the muscle tone of the sphincters that surround the lower part of the rectum. Therefore, imaging studies before 24 hours most likely will show a ‘very high rectum’ and may lead to an incorrect diagnosis. Historically, an invertogram was used to identify whether the anomaly is ‘high’ or ‘low’.58

During the first 24 hours, the neonate should receive intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nasogastric decompression, and be evaluated for associated defects that may represent a threat to life. These include cardiac malformations, esophageal atresia, and urinary defects.34,59 A radiograph of the lumbar spine and the sacrum should be obtained as well as a spinal ultrasound to evaluate for a tethered cord. Renal/abdominal ultrasound should be done to evaluate for hydronephrosis.

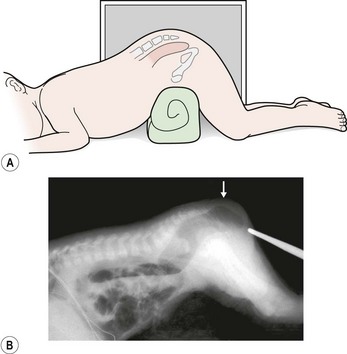

If the neonate has signs of a rectoperineal fistula, an anoplasty can be performed in the newborn period without a protective colostomy. After 24 hours, if there is no meconium on the perineum, we recommend obtaining a cross-table lateral radiograph with the patient in the prone position (Fig. 35-13A). If air in the rectum is seen distal to the coccyx (Fig. 35-13B), and the patient is in good condition with no significant associated defects, one may consider performing a posterior sagittal operation without a protective colostomy. A more conservative alternative would be to perform the posterior sagittal repair and a protective colostomy at the same stage.

FIGURE 35-13 Technique for a cross-table lateral radiograph. (A) A roll has been placed beneath the hips of the infant to elevate the buttocks and allow air to migrate superiorly to the end of the rectum. (B) Actual cross-table lateral radiograph. Air is visualized distal to the coccyx (arrow).

Performing the definitive repair early in life has important advantages including less time with an abdominal stoma, less size discrepancy between the proximal and distal bowel at the time of colostomy closure, and easier anal dilation (because the infant is smaller). In addition, at least theoretically, placing the rectum in the right location early in life potentially may represent an advantage in terms of acquired local sensation.60

All of these potential advantages of an early operation must be weighed against the possible disadvantages of an inexperienced surgeon who is not familiar with the anatomic structures of an infant’s pelvis. Operating on patients with anorectal malformations primarily without a protective colostomy has been done successfully, but may have negative consequences if the surgeon does not have the necessary preoperative evaluation and experience.29,61,62

A temptation to repair these defects without a protective colostomy always exists.27,61,62 Repair without a colostomy does not allow a distal colostogram which may be very helpful to the surgeon. The worst complications involve infants who undergo repair without a colostomy or a properly performed distal colostogram.63 Proceeding with the posterior sagittal approach looking blindly for the rectum has resulted in a spectrum of serious complications, including damage to the urethra, complete division of the urethra, pull-through of the urethra, pull-through of the bladder neck, injury to the ureters, and division of the vas deferens or seminal vesicles.63

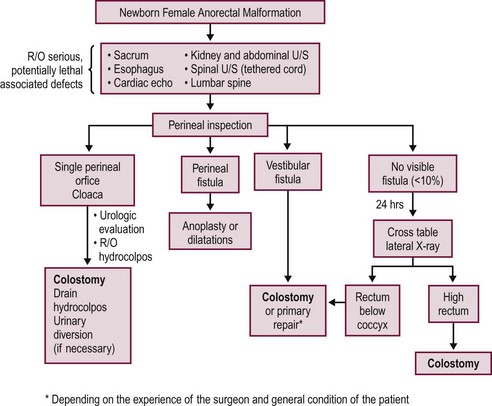

A decision-making algorithm for the initial management of newborn females is shown in Figure 35-14. Again, the perineal inspection is the most important step to guide diagnosis and decision making. The first 24 hours should also be used to evaluate for associated defects, as previously described. Perineal inspection may show the presence of a single perineal orifice, which establishes the diagnosis of a cloaca and carries a high risk of an associated urologic defect. Also, it should prompt a complete urologic evaluation, including abdominal and pelvic ultrasound, to look for hydronephrosis and hydrocolpos.

FIGURE 35-14 Decision-making algorithm for female newborns with anorectal malformations. U/S, ultrasonography; R/O, rule out.

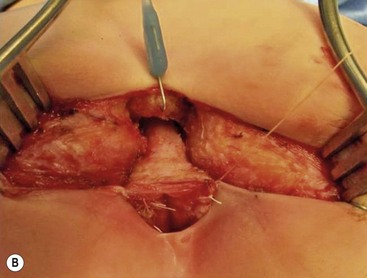

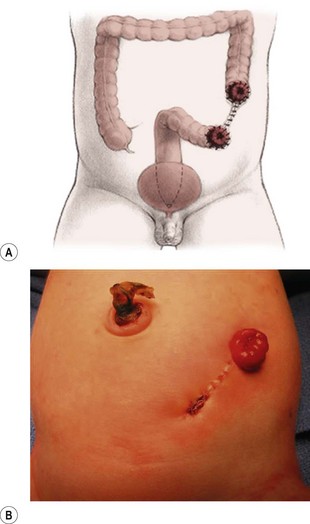

Patients with a cloaca require a colostomy. It is important to perform the divided sigmoid colostomy in such a manner as to leave enough redundant, distal rectosigmoid colon to allow for the subsequent pull-through (Fig. 35-15). When performing the colostomy for a cloaca, it is important to drain a hydrocolpos when present. This can be achieved with a curled catheter. Because a significant number of these patients have two hemivaginas, the surgeon must be certain that both hemivaginas are drained. Occasionally, a vaginovaginostomy in the vaginal septum needs to be created to drain both hemivaginas with one catheter. At times, the hydrocolpos is so large that it may produce respiratory distress. Also, the hydrocolpos can compress the trigone and cause hydronephrosis, and drainage of the hydrocolpos allows for decompression of the urologic system. Rarely, if the common channel is very narrow and does not allow the bladder to drain, the neonate may require a vesicostomy or suprapubic cystostomy to decompress the bladder. However, in most cases, drainage of the hydrocolpos is all that is required. Endoscopic examination of the cloaca is recommended to delineate the anatomy. This evaluation is best done several months later during a separate anesthetic because the neonatal perineum is swollen and endoscopy is difficult in the newborn.

FIGURE 35-15 An ideal colostomy for infants with high anorectal malformations is seen in (A) the drawing and (B) infant. Note the colostomy and mucous fistula are separated and that adequate distal colonic length remains for the subsequent rectal pull-through.

The presence of a vestibular fistula represents the most common finding in female infants (see Fig. 35-7). When newborns with a vestibular fistula undergo primary repair at our institution, we hospitalize the patient for seven days with no oral intake, and use concentrated dextrose intravenous nutrition. When the patient undergoes a primary repair of a vestibular fistula or perineal fistula without colostomy later in life, we are particularly strict about preoperative bowel preparation to ensure that the intestine is completely clean.

If the perineal inspection shows a rectoperineal fistula, we recommend performing a primary anoplasty without a colostomy. In fewer than 5% of girls, there is no visible fistula and there is no evidence of meconium after 24 hours of observation. This small group of patients requires a cross-table lateral prone radiograph (see Fig. 35-13). If the radiograph shows gas in the rectum very close to the skin, it means that the baby likely has a very narrow perineal fistula or has no fistula defect. If the baby is in stable condition, one can perform a primary operation without a colostomy, depending on the surgeon’s experience. Most of these patients without a fistula also have Down syndrome.19 If associated conditions make the rectal repair not feasible in the newborn period, a colostomy should be performed, with definitive repair later.

Occasionally, if the infant with a rectoperineal or rectovestibular fistula has significant associated defects or is unstable, the surgeon may elect to dilate the fistula to facilitate emptying of the colon while these other issues are addressed. Definitive repair can be performed in a few months.

A divided descending colostomy is ideal for the management of anorectal malformations when diversion is needed (see Fig. 35-15). The completely diverting colostomy provides bowel decompression as well as protection for the final reconstruction. In addition, the colostomy is used for the distal colostogram, which is the most accurate diagnostic study to determine the detailed distal anatomy.64–66

The descending or upper sigmoid colostomy has definitive advantages over a right or transverse colostomy.65 It is important to have a relatively short segment of defunctionalized distal colon, but not too short as to interfere with the subsequent pull-through. The ideal location is just at the point where the proximal sigmoid comes off the left retroperitoneum. Mechanical cleansing of the distal colon at the time of colostomy is much less difficult when the colostomy is located in the descending portion of the colon. In the case of a large rectourethral fistula, the patient may pass urine into the colon. A more distal colostomy allows urine to escape through the distal stoma without significant absorption. With a more proximal colostomy, the urine remains in the colon and is absorbed, leading to metabolic acidosis. A loop colostomy permits the passage of stool from the proximal stoma into the distal bowel. This can lead to urinary tract infections, distal rectal pouch dilation, and fecal impaction (Fig. 35-16). Prolonged distention of the rectal pouch may produce a megarectosigmoid, leading to severe constipation later in life. Also, the problem of colostomy prolapse is more frequent with loop colostomies.65

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree