Materials and Methods

Performing this study required unique access to well-defined cadaveric specimens in which age, parity status, delivery mode and a history of symptomatic PFDs could be determined unambiguously. Thus, we partnered with the University of Minnesota Bequest Body Donation Program, which provides access to donors’ medical records. The study was exempt from institutional review board approval because of the exclusion of living human subjects. Specimens were obtained from donors who had no history of PFDs or rectal prolapse to eliminate potential confounding effects of disease on architecture. Donors with a history of pelvic radiation, gynecologic or colorectal malignancy, pelvic metastasis, connective tissue disorder, myopathy, colectomy, or proctectomy were also excluded. In contrast to vaginal delivery, PFM injury is rarely observed after cesarean childbirth, and PFM strength is unchanged by abdominal deliveries. Thus, nulliparous donors (n = 8) and donors with a history of cesarean deliveries only (n = 3) were designated as vaginally nulliparous . Over a 2.5-year period, we accumulated 23 specimens that enabled statistical comparison among the following 4 groups: younger vaginally nulliparous (YVN; n = 5), younger vaginally parous (YVP; n = 6), older vaginally nulliparous (OVN; n = 6), and older vaginally parous (OVP; n = 6). Based on epidemiologic studies, age surpasses parity as a risk factor for PFDs after menopause, which is a marker of biologic senescence in women. Using statistics from the National Institute of Aging, the average age of menopause in the United States is 51 years. Thus, we defined younger as ≤51 years and older as >51 years, which is consistent with previously reported onset of age-related sarcopenia in appendicular muscles in the sixth decade of life.

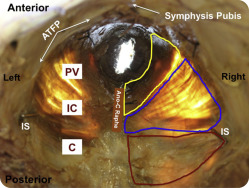

Muscle architecture

To maintain in vivo architectural structure, coccygeus (C), iliococcygeus (IC), and pubovisceralis (PV), consisting of pubococcygeus and puborectalis, were perfusion fixed in situ (ie, attached to the skeleton) via injection of formaldehyde through the common carotid artery, in contrast to most studies that immersion fix tissues. PFMs were harvested en block and separated into individual muscles, identified by tracking each muscle along its length, weighed, and divided into cephalad, middle, and caudate regions, as previously described. Muscle thickness was measured with electronic calipers to the nearest 0.01 mm in each region. The following architectural parameters were determined with the use of validated methods : muscle mass; physiologic cross-sectional area (PCSA), which is a predictor of isometric force generation capacity; fiber length, which is a predictor of muscle excursion and contractile velocity; and sarcomere length (L s ), which determines the force that is produced when muscle is stimulated. Three fiber bundles were dissected from each region, and fiber length was measured with electronic calipers to the nearest 0.01 mm.

Myofibers were isolated from each bundle under a dissecting microscope with a 6X objective and an overall magnification of 60X (Leica MZ16; Meyer Instruments Inc, Houston, TX) and mounted on a slide for L s determination by laser diffraction. The fixation process shortens L s by approximately 10% of its in vivo length; thus, L s provides information regarding a muscle’s in vivo sarcomere length. L s is also used to calculate the number of sarcomeres in series within fibers to normalize fiber length (L fn ) and correct for potential differences in length among specimens at the time of fixation. PCSA was calculated as previously described, with the use of an optimal human sarcomere length of 2.7μm.

Intramuscular ECM

PFMs have a composite structure that consists of the contractile myofibers embedded within a large connective tissue network of ECM, which primarily consists of collagen. Muscle ECM determines muscle passive mechanical properties and ability to sustain load. Pathologic accumulation of intramuscular collagen or fibrosis negatively impacts muscle mechanical properties and may account for the insensitivity to rehabilitation of limb skeletal muscles. Elucidating the impact of vaginal delivery and aging on the PFM intramuscular ECM is important to advance our understanding of potential changes in muscle properties and lead to novel therapies. Hydroxyproline quantification was used to define intramuscular collagen content with the use of a validated protocol. Total collagen content was determined by the conversion of hydroxyproline concentration with the constant of 7.46, which is the number of hydroxyproline residues per collagen molecule.

Statistical analyses

A fully crossed experimental design was used to assess independently the effects of parity and aging on individual PFMs. The main effects of parity and aging and their interaction were determined by 2-way and repeated measures analysis of variance, followed by multiple comparisons with Tukey’s range test, as appropriate. The important interaction term addressed the following question: Does vaginal parity alter the effects of aging on PFM structural properties? Demographic variables were compared among groups by 1-way analysis of variance and Student t test. Significance level (α) was set to 5%. To obtain 80% power (1-β) to detect a 20% difference, the sample size of 5 per group was calculated with the following equation: n = (CV) 2 /(ln[1 – δ]) 2 using the experimental variability from the YVN group with variables “n = sample size,” “δ = difference desired (15%)” and “CV = coefficient of variation.” All data were screened for normality and skew to satisfy the assumptions of the parametric tests that were used. Results are presented as mean ± SEM, except where noted. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (version 6.00; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

The difference in the mean age of donors between younger and older groups was highly significant and nearly 40 years ( Table 1 ), which permitted a meaningful quantification of an age effect. Within study groups, the age of nulliparous and parous donors did not differ ( Table 1 ), which ensured that ages of subgroups did not confound the experimental design and obviated the need for analysis of covariance. Also importantly, body mass index was similar for all groups and eliminated another potential confound ( Table 1 ). Younger and older parous donors did not differ with respect to parity ( Table 1 ). During dissection, gross disruption at entheses, lateral attachments to the arcus tendineus levator ani, or within muscle bellies were not observed in any of the 23 specimens. There were no differences between the right and left sides or the 3 regions of the individual muscles. All PFMs were extremely thin, as previously reported, nearly transparent, irrespective of age or parity, with similar muscle thickness among groups ( Figure 1 ). Among individual PFMs, the thickness of C was 3.1 ± 0.2 mm, which was significantly greater than 1.7 ± 0.1 mm and 1.9 ± 0.1 mm thickness of IC and PV, respectively ( P < .001).

| Variable | Mean age, y (SEM) | Mean body mass index, kg/m 2 (SEM) | Median parity, n (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||

| Younger vaginally nulliparous (n = 5) | 40.4 (5.4) | 21.1 (2.6) | |

| Younger vaginally parous (n = 6) | 43.5 (2.4) | 20.8 (1.8) | 2 (1-3) |

| Older vaginally nulliparous (n = 6) | 80.0 (6.7) | 19.2 (1.6) | |

| Older vaginally parous (n = 6) | 81.0 (7.7) | 17.8 (1.1) | 2 (1-4) |

| Probability value | |||

| Younger vaginally nulliparous vs younger vaginally parous | .98 a | .99 a | |

| Younger vaginally nulliparous vs older vaginally nulliparous | .001 a | .89 a | |

| Younger vaginally nulliparous vs older vaginally parous | .001 a | .62 a | .76 b |

| Older vaginally nulliparous vs older vaginally parous | .99 a | .94 a |

a Derived from Tukey’s pairwise comparisons, according to 2-way analysis of variance

b Derived from the Student t test, with significance level set to 5%.

Muscle architecture

Vaginal parity and aging had significant, but differential effects on PFM architecture; and the magnitude of the effect varied by muscle, as illustrated by the percent of total variation and the mean squares term ( Table 2 ). There were no significant interactions between aging and vaginal parity ( Table 2 ). The relationship between the PCSA and normalized fiber length expresses both the force-producing and excursion capability of a muscle and is displayed for the individual PFMs in each group in Figure 2 . The main impact of parity was increased fiber length in the more proximally located C and IC; aging-related changes manifested as decreased PCSA across all PFMs ( Figure 2 ).

| Muscle | Percentage of total variation, % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized fiber length | Physiologic cross-sectional area | Sarcomere length | Muscle mass | |||||||||

| Parity | Aging | Interaction | Parity | Aging | Interaction | Parity | Aging | Interaction | Parity | Aging | Interaction | |

| Coccygeus | 48.9 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 47.8 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 26 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 34.9 | 0.05 |

| Mean squares a | 714.3 | 46.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.0005 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 5.4 | 19.4 | 0.03 |

| P value b | .0003 | .3 | .8 | .3 | .0003 | .2 | .9 | .01 | .2 | .08 | .002 | .9 |

| Iliococcygeus | 50.5 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 3.4 | 32.9 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 0.03 | 4.9 | 31.6 | 4.1 |

| Mean squares a | 1146.0 | 8.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.0005 | 3.1 | 19.7 | 2.6 |

| P value b | .0003 | .7 | .9 | .3 | .005 | .2 | .6 | .5 | .9 | .2 | .005 | .3 |

| Pubovisceralis | 12.4 | 11.9 | 10.5 | 3.8 | 31.7 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 0.003 | 14.9 | 11.8 |

| Mean squares a | 349.2 | 337.7 | 296.7 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 15.2 | 12.0 |

| P value b | .07 | .07 | .09 | .3 | .005 | .2 | .9 | .6 | .4 | .9 | .07 | .1 |

a Measure contribution of parity, aging, and interaction terms to the variation in the pelvic floor muscle architectural parameters

b Derived from F-statistics with significance level set to 5%.

Impact of vaginal parity on PFMs

Vaginal delivery resulted in a significantly longer normalized fiber length (L fn ) in C and IC in parous, relative to nulliparous, specimens in both younger and older groups. C L fn increased by 38% in younger ( P = .02) and 30% in older group ( P = .04); IC L fn increased by 31% in younger ( P = .03) and older groups ( P = .02; Figure 3 ). However, PV L fn did not differ between vaginally nulliparous and parous groups, irrespective of age (younger: P > .9; older: P = .07). PCSA was lower in all PFMs in YVP compared with YVN specimens; however, the differences did not reach statistical significance ( Figure 4 ). In the older group, vaginal delivery did not impact PCSA ( Figure 4 ). PFMs in the YVN and YVP groups had L s near optimal sarcomere length ( Figure 5 ). Muscle mass did not differ between parous and nulliparous specimens in either younger or older groups ( Figure 6 ).

Impact of aging on PFMs

In contrast to vaginal delivery, aging did not impact L fn ( Figure 3 ). However, PCSA of all muscles was significantly lower in the OVN group, compared with the YVN group, with a dramatic decrease of 43% in C ( P < .01), 42% in IC ( P = .03), and 50% in PV ( P = .02; Figure 4 ). Importantly, the age-related decrease in PCSA was not significant in the YVP group, compared with the OVN group, with a 30% decline in C ( P = .1), 26% in IC ( P = .4), and 31% in PV ( P = .5; Figure 3 ). Furthermore, PFM PCSA did not differ between the YVP and OVP groups ( P > .1; Figure 4 ). Sarcomere length was significantly shorter in C in the OVN group, compared with YVN group: 2.46 vs 2.75μm ( P = .04). Maximum myosin-actin overlap, and the associated maximum active tension that muscle generates on stimulation, occurs at L s of 2.7μm in human muscle. Thus, the shorter L s in OVN specimens would result in lower C active force production. The extent of age-related decrease in muscle mass was substantially smaller than the changes that were observed in PCSA ( Figure 6 ).

Intramuscular ECM

Similar to the distinct impact on PFM architecture, vaginal delivery and aging had a differential main effect on PFM extracellular matrix total collagen content, with variable magnitude of the effect on the individual PFMs. Collagen content was not altered by parity in either younger or older groups ( Table 3 ). On the other hand, aging resulted in a dramatic increase in intramuscular collagen in all PFMs of OVN, compared with YVN, with 44% in C ( P = .03), 51% in IC ( P = .03), and 72% in PV ( P = .02) ( Table 3 ).