Immunization

Neal A. Halsey

Immunizations are among the most efficacious and cost-effective interventions available to improve the health and well-being of children. In the second half of the twentieth century, smallpox has been eradicated, wild-type poliomyelitis viruses have been eliminated from all but a few countries, and the global efforts to eradicate wild-type polioviruses from the world should be completed by the time this book is published. Measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infections have been reduced to levels that are 99% or more lower than the prevaccination era in the United States.

Several vaccines have been added to the routine immunization schedule in recent years, including hepatitis B, varicella, and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines that have already had an impact on childhood disease; other vaccines in development will prevent additional infectious diseases and cancers, further reducing the burden of disease in children and adults.

ROUTINE IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULE

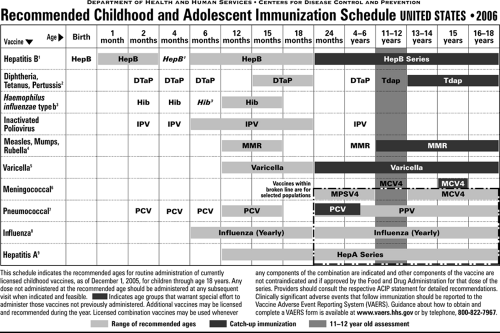

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) jointly prepare an updated immunization schedule every January, which is published in the Pediatrics, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in Family Physician (Fig. 15.1).

Locations of Current Immunization Information

The schedule and other valuable information about recommended vaccines can be found on the CDC’s Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/nip). Readers are encouraged to obtain updated schedules every year and familiarize themselves with the changes. Specific information regarding each vaccine and details regarding the immunization process are available in the Red Book (Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases), which is published every 3 years. The CDC also publishes a document entitled “General Guidelines on Immunization” (http://www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/acip-list.htm), which summarizes key recommendations and is updated periodically.

The annual updating of the Recommended Childhood and Adolescent Immunization Schedule reflects the rapidly changing field of immunizations and the need for physicians to have access to this information in a timely manner.

Web sites with the most recent guidelines are maintained by the CDC’s ACIP (http://www.cdc.gov/nip/acip) and the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases (http://www.aap.org). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also maintains a detailed Web site with valuable information on vaccines, additives, recalls, the approval process, and recent recommendations of advisory committees (http://www.fda.gov/cber/vaccines.htm). Additional general information on immunization is available on the Immunization Action Coalition’s Web site (http://www.immunize.org). Information on vaccine safety is available on the Institute for Vaccine Safety’s (http://www.vaccinesafety.edu), the FDA’s, and the CDC’s Web sites.

Vaccine Information Statements and Record Keeping

Health care providers are required to provide specific information to parents before administering vaccines. Vaccine information statements are updated periodically by the CDC and are available from health departments, the CDC’s Web site, and the AAP. Physicians are required by law to maintain careful immunization records on all children under their care, including the type of vaccine administered, lot number, manufacturer, date of immunization, and clinic or office where the vaccine was administered. Assistance with record keeping is available from both the AAP and the CDC; efforts are under way to label every vaccine vial with bar codes to simplify the data-collecting process for physicians.

Additional information is available on package inserts included with each vaccine. At times, the guidelines from advisory committees are in conflict with information in the package insert. Advisory committees take into account societal factors and incorporate knowledge from other vaccines to provide guidelines when data are limited. Vaccine companies are permitted to seek approval for indications supported by data specific to their product, and the companies often add cautions or contraindications to circulars to protect themselves from possible litigation in areas of uncertainty.

Catch-Up Immunization Schedules

For children who are behind in the immunization schedule, including recent adoptees without evidence of previous immunizations, an accelerated immunization schedule is recommended (Tables 15.1a and 15.1b).

Schedule for Adoptees

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the immunization schedule presented in Table 15.2. In general, vaccines produced in other countries meet WHO standards, and written immunization records from a reliable source indicating receipt of these vaccines should suffice for adequate evidence of protection against the diseases. Although the intervals for administering the first three doses of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine and oral poliovirus (OPV) vaccine are shorter than routinely recommended in the United States, these schedules have been shown to be effective and are acceptable for DTP and OPV. Recent data generated in the United Kingdom indicate that the Hib vaccine administered at 2, 3, and 4 months of age may not have provided optimal protection against disease when no booster dose was given. Verbal immunization histories for adopted children generally should not be accepted. In most developing countries, several vaccines that are routinely administered to children in the United States are often not available, including rubella, mumps, varicella, and Hib vaccines. The use of the hepatitis B vaccine has increased in developing countries, with more than 100 countries administering the vaccine in programs to all infants. When doubt exists regarding the accuracy of immunization records, children should be reimmunized in accordance with the catch-up immunization schedule (see Tables 15.1a and 15.1b).

Lapsed or Delayed Immunizations

Intervals longer than recommended for routine immunization are commonly encountered in children who do not have regular health care providers or who have lived overseas. Intervals longer than recommended are not an indication for restarting the immunization schedule at any age. Immunologic memory is induced by one or two doses of vaccine, which appears to be long lasting. Even if a sufficient response was not induced to provide long-term protective levels of antibody, subsequent doses administered years later induce a secondary antibody response to tetanus, diphtheria, hepatitis B, and other vaccines. For live viral vaccines, the purpose of the second (or third) dose is to induce immunity in children who did not respond to the first vaccine. Therefore, intervals are not an important variable to consider when administering vaccines to children with delayed or lapsed immunization. The appropriate number of doses needed to complete the series should be administered.

Immunization Tracking

Physicians are actively encouraged to maintain a formal tracking system to identify infants and young children who are deficient in immunizations. Special software is available through the CDC to assist with tracking and assessing the immunization status of all children in a pediatric practice.

TABLE 15.1A. FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WHO START LATE OR WHO ARE MORE THAN 1 MONTH BEHIND UNITED STATES, 2006 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 15.1B. FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WHO START LATE OR WHO ARE MORE THAN 1 MONTH BEHIND UNITED STATES, 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF IMMUNIZATION

Vaccines

Vaccines act by stimulating specific immune responses that prevent either infection or disease from the naturally occurring organisms. Several methods have been used to produce the vaccines that are in use today (Table 15.3).

Passive Immunization

Passive immunization involves the administration of preformed antibody in the form of intramuscular immunoglobulin, intravenous immunoglobulin (IGIV), or concentrated monoclonal antibodies. Specific immunoglobulin preparations and their indications are shown in Table 15.4.

TABLE 15.2. IMMUNIZATION SCHEDULE OF THE EXPANDED PROGRAM ON IMMUNIZATION OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATIONA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most passive immunization is administered after high-risk exposure to individuals who have not been immunized against the disease in question and to those at high risk of severe complications, such as children born to women who are chronic carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen. Preexposure prophylaxis occurs in patients with underlying immune deficiency disorders who are incapable of developing protective levels of antibody after immunization or in persons who are at increased risk of exposure and cannot receive a vaccine, such as children under 2 years of age who need to be protected against hepatitis A infections. Replacement immune globulin therapy for patients with immune deficiency disorders requires monthly infusions of IGIV.

Adverse reactions have occurred after administration of all immunoglobulin preparations, but these reactions are usually mild and self-limited. Fever and chills occur at times during infusion of IGIV. Aseptic meningitis occurs in less than 1% of IGIV recipients, but headache, myalgia, light-headedness, nausea, and vomiting occur somewhat more commonly. Flushing, hypertension, and tachycardia can occur from vasomotor instability or volume overload. Hypersensitivity reactions occur rarely, but selective IgA-deficient individuals develop antibodies to IgA after infusions of IGIV. Therefore, IgA-deficient individuals normally do not receive replacement immunoglobulin therapy. In rare instances when therapy is needed, IgA-depleted IGIV is indicated.

All human immunoglobulin and other blood-derived preparations carry a theoretical risk of transmission of infectious agents. Multiple procedures are required in the preparation of the products to ensure the inactivation of all known transmissible agents, but the potential exists for unknown agents to be transmitted, as occurred before identification of the hepatitis C virus.

Vaccine Handling and Storage

Most vaccines should be maintained at refrigerator temperature (2°C to 8°C, 36°F to 46°F). Some vaccines, however,

require maintenance at freezer temperatures (e.g., OPV, varicella vaccine), and the temperature requirements for the varicella vaccine are more stringent than for OPV. Lyophilized vaccines can be frozen without harm, but several liquid vaccines (e.g., DTP, inactivated poliovirus [IPV], and hepatitis B) lose potency with freezing because of disruption of bonding with adjuvants, chemical separation, or disruption of antigens. Specific guidelines are available in package inserts.

require maintenance at freezer temperatures (e.g., OPV, varicella vaccine), and the temperature requirements for the varicella vaccine are more stringent than for OPV. Lyophilized vaccines can be frozen without harm, but several liquid vaccines (e.g., DTP, inactivated poliovirus [IPV], and hepatitis B) lose potency with freezing because of disruption of bonding with adjuvants, chemical separation, or disruption of antigens. Specific guidelines are available in package inserts.

TABLE 15.3. TYPES OF IMMUNIZING AGENTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sites of Administration

Sites of administration are listed in Box 15.1. The preferred site for intramuscular administration of vaccines is the anterolateral thigh or the deltoid muscle. The anterolateral thigh is usually chosen for infants and toddlers, but some physicians prefer to administer intramuscular injections in the deltoid after 15 months of age to minimize the effect of local reactions on ambulation. The buttocks generally should not be used for immunization because of possible inadvertent damage to the sciatic nerve and the possibility of decreased immunogenicity. The ventrolateral gluteal site is preferred when it is necessary to use the buttocks for injection of large volumes of immunoglobulins. Administration of all vaccines in the recommended schedule may require multiple injections per visit. More than one injection can be given into the same extremity as long as the injections are separated by enough distance to differentiate local reactions, generally 1 to 2 inches.

TABLE 15.4. PASSIVE IMMUNIZATION PRODUCTS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recommendations for needle length vary. For subcutaneous injections, 3/8- to 5/8-inch needles are adequate at any site.

The depth of subcutaneous fat tissue varies by site, age, and nutritional status. For intramuscular injections, the technique used can affect the depth to muscle tissues. The best general advice is to be certain that the needle is long enough to penetrate the middle of the muscle mass and to use the technique that is most appropriate for the size of the individual receiving the intramuscular injection. When the muscle is bunched up, the depth of subcutaneous fat is increased. When the muscle is bunched and the needle is inserted at a 45-degree angle, a 7/8- to 1-inch needle is appropriate for intramuscular injections in infants and most children. However, 5/8-inch needles are appropriate for newborns and have been used successfully in infants younger than 6 months when the injection technique involves flattening of the subcutaneous tissue and injecting at a 90-degree angle. For administration of intramuscular injections in the deltoid muscle, needles of 7/8- to 1-inch in length usually are sufficient in children from 4 to 18 years of age. For females weighing more than 80 kg, a 11/2-inch needle is needed, and for females weighing more than 120 kg, a 2-inch needle may be necessary.

The depth of subcutaneous fat tissue varies by site, age, and nutritional status. For intramuscular injections, the technique used can affect the depth to muscle tissues. The best general advice is to be certain that the needle is long enough to penetrate the middle of the muscle mass and to use the technique that is most appropriate for the size of the individual receiving the intramuscular injection. When the muscle is bunched up, the depth of subcutaneous fat is increased. When the muscle is bunched and the needle is inserted at a 45-degree angle, a 7/8- to 1-inch needle is appropriate for intramuscular injections in infants and most children. However, 5/8-inch needles are appropriate for newborns and have been used successfully in infants younger than 6 months when the injection technique involves flattening of the subcutaneous tissue and injecting at a 90-degree angle. For administration of intramuscular injections in the deltoid muscle, needles of 7/8- to 1-inch in length usually are sufficient in children from 4 to 18 years of age. For females weighing more than 80 kg, a 11/2-inch needle is needed, and for females weighing more than 120 kg, a 2-inch needle may be necessary.

BOX 15.1 Sites of Administration