Chapter 452 Hereditary Spherocytosis

Etiology

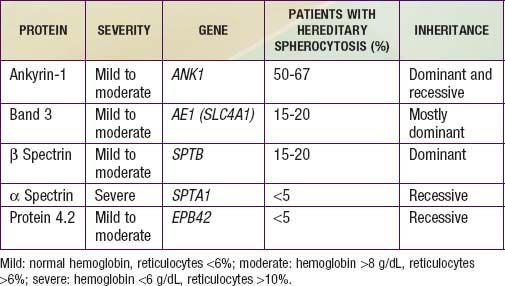

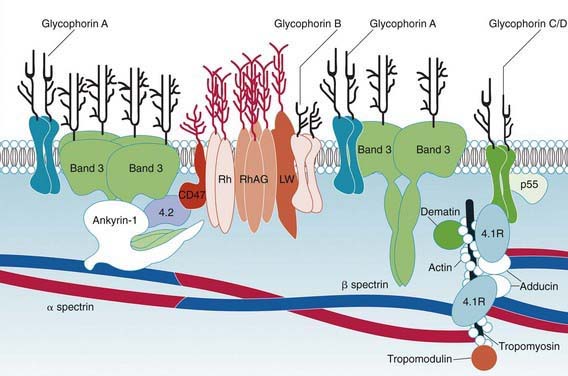

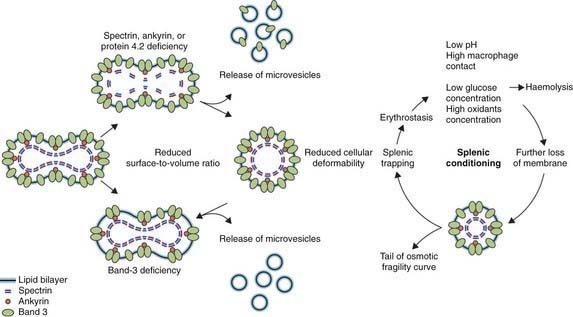

Hereditary spherocytosis usually is transmitted as an autosomal dominant or, less commonly, as an autosomal recessive disorder. As many as 25% of patients have no previous family history. Of these patients, most represent new mutations, and a few cases result from recessive inheritance or represent nonpaternity. The most common molecular defects are abnormalities of spectrin or ankyrin, which are major components of the cytoskeleton responsible for RBC shape. A recessive defect has been described in α-spectrin. Dominant defects have been described in β-spectrin and protein 3. Dominant and recessive defects have been described in ankyrin (Table 452-1). A deficiency in spectrin, protein 3, or ankyrin results in uncoupling in the “vertical” interactions of the lipid bilayer skeleton and the loss of membrane microvesicles (Figs. 452-1 and 452-2). The loss of membrane surface area without a proportional loss of cell volume causes sphering of the RBCs and an associated increase in cation permeability, cation transport, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) use, and glycolysis. The decreased deformability of the spherocytic RBCs impairs cell passage from the splenic cords to the splenic sinuses, and the spherocytic RBCs are destroyed prematurely in the spleen. Splenectomy markedly improves RBC life span and cures the anemia.

Clinical Manifestations

Hereditary spherocytosis may be a cause of hemolytic disease in the newborn and can manifest as anemia and hyperbilirubinemia sufficiently severe to require phototherapy or exchange transfusions. Hemolysis may be more prominent in the newborn because hemoglobin F binds 2,3-diphosphoglycerate poorly, and the increased level of free 2,3-diphosphoglycerate destabilizes interactions among spectrin, actin, and protein 4.1 in the RBC membrane (see Fig. 452-1).

Because of the high RBC turnover and heightened erythroid marrow activity, children with hereditary spherocytosis are susceptible to aplastic crisis, primarily as a result of parvovirus B19 infection, and to hypoplastic crises associated with various other infections (Fig. 452-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree