KEY POINTS

• Distinguishing between pregnancy-induced liver problems and liver problems related to maternal disease is crucial and often challenging.

• Pregnancy-induced liver disease presents significant risks for maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

• Pregnancy should not adversely affect mild to moderate maternal liver disease.

• Pregnancy in patients with portal hypertension and esophageal varices carries a high risk of life-threatening hemorrhage.

BACKGROUND

It is necessary to understand the characteristic alterations of hepatic function common to pregnancy in order to differentiate normal physiologic changes from abnormalities attributable to disease states.

Pathophysiology

• There is no change in the size of the liver during pregnancy.

• There is no change in blood flow during pregnancy.

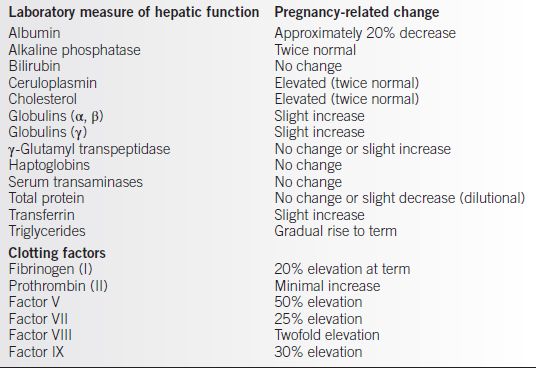

• Biochemical changes (see Table 15-1)

• Serum albumin decreases due to increasing plasma volume.

• Increase in alkaline phosphatase level due to increased placental production and increased bone turnover.

• Increased production of clotting factors.

Table 15-1 Pregnancy-Related Changes in Laboratory Measures of Hepatic Function

EVALUATION

History and Physical

• Common complaints with hepatic dysfunction

• Right upper quadrant pain

• Nausea and vomiting

• Pruritus

• Common physical findings with hepatic dysfunction

• Jaundice.

• Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly.

• Palmar erythema and spider angiomata do not correlate with liver disease in pregnancy.

Laboratory Tests

• Liver function tests: a broad range of serum chemistries that typically includes aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), 5′-nucleotidase, serum bilirubin, serum albumin, and bile acids

• Coagulation studies

• Sonography

PREGNANCY-RELATED HEPATIC DISEASE STATES

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

Background

• Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a liver disorder in pregnancy occurring in about 1 in 500 pregnancies. It is the second most common cause of jaundice in pregnancy.

Definition

• Pruritus of the trunk and extremities (palms and soles of the feet) beginning in the third trimester is the hallmark of this disease. The itching is often intense and unrelenting.

Pathophysiology

• Pruritus is thought to result from deposition of bile salts in the subcutaneous tissue and skin.

Etiology

The exact etiology is unknown but theories include

• A defect in biliary transport of bile secretion(1)

• Receptor changes affecting detoxification of bile acids (2)

• A possible link to maternal estrogen and progesterone levels (3)

Epidemiology

• The incidence is increased in Scandinavians and Chilean Indians.

• The disease is rare in African Americans.

• Seasonal variations have been noted, with more cases seen in the fall (November).

Evaluation

History and Physical

• Pruritus usually begins after 26 weeks (third trimester) and becomes more intense as pregnancy advances.

• It is not associated with a rash, but excoriations may be present.

• Distribution is typically across the trunk, extremities, palms, and soles.

• Pruritus resolves with delivery.

• Frequently, a history exists of ICP in a previous pregnancy, another family member, or similar symptoms with oral contraceptive pill use.

Jaundice

• Usually mild

• Develops in 10% to 25% of patients with ICP (4)

• Usually begins 1 to 4 weeks after the onset of pruritus

Laboratory Tests

• Serum bile acid levels are increased (4).

• Increase in serum bilirubin (predominately conjugated) may be up to six times greater than the upper limit of normal (5).

• Transaminases may be elevated 2 to 10 times greater than the upper limit of normal.

Genetics

• Possibly an autosomal dominant trait

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

• Viral hepatitis

• Gallbladder disease

Clinical Manifestations

• In addition to severe pruritus, the patient may have anorexia, steatorrhea, and dark urine.

Treatment

• Treatment is used primarily to relieve symptoms until the fetus is mature enough for delivery.

Medications

• Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the treatment of choice (10 to 15 mg/kg/d) (3).

• Antihistamines for symptomatic relief of pruritus.

• Corticosteroids—dexamethasone 12 mg/d.

• Cholestyramines—8 to 16 g/d in divided doses.

Procedures

• Begin antenatal fetal assessment (biophysical profile or nonstress testing) at the time of diagnosis.

• Delivery at 37 weeks of gestation (6).

Risk Management

• No test reliably predicts fetal demise (7).

• Majority of fetal deaths occur after 37 weeks (6).

• Mother should begin supplemental vitamin K at the time of diagnosis.

Complications

Long-term maternal complications are not seen with ICP, but there are several pregnancy-related complications:

• Increased perinatal mortality

• May be related to maternal serum bile acid level

• Fetal mortality rate of 11% to 20% when untreated (6).

• Fetal testing is not always predictive of imminent fetal death.

• Preterm delivery

• Meconium-stained amniotic fluid

• Postpartum hemorrhage

Patient Education

The pregnant patient should be counselled regarding

• The increased risks of preterm labor and delivery

• The signs and symptoms of preterm labor

• The increased risk of intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD) and regular fetal movement counts

• A 45% to 70% risk of ICP recurring in subsequent pregnancies (4)

Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, and Low Platelets (HELLP) Syndrome and Preeclampsia (see Chapter 11, Preeclampsia)

Background

Preeclampsia affects 5% to 7% of all pregnancies and is characterized by new-onset hyper-tension and proteinuria. It often has significant hepatic effects including reduced perfusion, abnormal liver function, and edema of the hepatic parenchyma and capsule. A variant of severe preeclampsia is the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome. HELLP syndrome affects 5% to 10% of patients diagnosed with preeclampsia and is associated with several significant complications (8).

Pathophysiology

The manifestations of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome are thought to be the results of

• Placental hypoperfusion

• Endothelial cell dysfunction

• Alteration of vasomotor tone

• Activation of coagulation cascade

• Release of proinflammatory mediators

Liver biopsy reveals

• Periportal hemorrhage and parenchymal necrosis

• Fibrin deposition in sinusoids

• Steatosis

Etiology

• Exact etiology is unknown; see Chapter 11, Preeclampsia for details.

Epidemiology

• Usually seen in older, multiparous Caucasian patients.

• Generally occurs in late second or third trimester, although 30% of cases occur postpartum.

• HELLP syndrome affects 5% to 10% of pregnancies with severe preeclampsia (8).

Evaluation

Physical Exam

Presenting signs and symptoms can be vague and variable. The most common symptoms are

• Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

• Nausea and vomiting

• Malaise

• Nondependent edema

The physical exam is often consistent with preeclampsia:

• Hypertension is usually present but may not be in the severe range.

• Significant peripheral edema and sudden weight gain often occur.

• Hyperreflexia is typically present.

Laboratory Tests

The diagnosis of HELLP syndrome requires evidence of

• Hemolytic anemia

• Abnormal peripheral smear

• Elevated serum bilirubin (greater than 1.2 mg/dL) (9)

• Low serum haptoglobin

• Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, greater than 600 U/L) (9)

• Significant drop in hemoglobin

• Elevated liver enzymes

• Abnormal transaminases (greater than 70 units/L or greater than two times upper limit of normal) (9)

• Abnormal bilirubin level

• Low platelets

• Must be less than 100,000 (9).

• Severity of low platelets appears to predict the severity of the disease (10).

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

• Pancreatitis

• Idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura

• Cholecystitis

• Appendicitis

• Pyelonephritis

• Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP)

• Signs and symptoms are similar to HELLP.

• AFLP often lacks hypertension and proteinuria.

• Liver function tests are not as intensely abnormal.

• Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS)

• Usually seen in children.

• There is typically more renal involvement.

• In pregnancy, HUS most often occurs postpartum.

• Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

• Neurologic symptoms

• Fever

Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis of HELLP should be considered in any patient with preeclampsia or who presents in the late second or third trimester with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, especially if the pain is in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Treatment

Management

Management of HELLP is the same as that for severe preeclampsia.

• Seizure prophylaxis, usually with magnesium sulfate (MgSO4)

• Control of blood pressure

• Corticosteroids to enhance fetal lung maturity if indicated

• Delivery

Counseling

• Risk of recurrence with subsequent pregnancies is 2% to 20% (9).

Complications

HELLP syndrome has a high rate of significant maternal complications:

• Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC).

• Acute renal failure.

• Eclampsia.

• Abruptio placentae.

• Pulmonary edema.

• Intracranial hemorrhage.

• Postpartum hemorrhage.

• Hepatic rupture.

• Maternal and fetal mortality is more than 50% when there is rupture of the liver or rupture of a subcapsular liver hematoma (9).

• Usually occurs in the anterior aspect of the right lobe of the liver (9).

• Surgical emergency.

• Fetal morbidity and mortality are related to the degree of prematurity and presence of intrauterine growth restriction.

• Maternal mortality rate may be as high as 50% (4).

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

Background

AFLP is a rare complication of pregnancy affecting approximately 1 in 10,000 pregnancies. It usually presents after 30 weeks’ gestation and may be associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality if not treated aggressively or if it goes unrecognized.

Pathophysiology

With AFLP, there is centrilobular, microvesicular fatty infiltration of the hepatocytes. This leads to mitochondrial disruption and widespread hepatic necrosis. Fulminant hepatic failure results if treatment (i.e., delivery) is delayed.

Etiology

• The exact etiology is unknown.

• Recent studies suggest an abnormality in the maternal and fetal metabolism of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA). In 31% to 79% of pregnancies with AFLP, there was a deficiency in fetus had long-chain three-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase (LCHAD) (11).

• LCHAD functions in the mitochondrial trifunctional complex, which is responsible for oxidation of fatty acids (12). With LCHAD deficiency, the fetus is unable to metabolize LCFAs, and excessive LCFA metabolites accumulate in the maternal liver where they are hepatotoxic (2).

Epidemiology

• AFLP is more common in

• Patients with multiple gestation

• Nulliparous patients

• Male fetus (3:1 male-to-female ratio)

• Preeclampsia is present in about 50% of the cases.

Evaluation

History and Physical

• Presents in the third trimester of pregnancy (usually greater than 30 weeks’ gestation).

• Nausea and vomiting are the most common presenting symptoms (75% of patients) (13).

• Abdominal pain is present in 51% of patients (13).

• Jaundice is common.

• Twenty percent to forty percent of patients will have signs or symptoms of preeclampsia.

Laboratory Results

• Liver transaminases are elevated 3 to 10 times normal but usually less than 1000 international units/L.

• Bilirubin is often greater than 10 mg/dL.

• Serum ammonia is elevated.

• Hypoglycemia (a poor prognostic sign).

• Alkaline phosphate is elevated 5 to 10 times normal.

• Lactic acidosis.

• Coagulation profile is often affected.

• Hypofibrinogenemia (vitamin K–dependent factors [II, VII, IX, X] are decreased).

• Thrombocytopenia (less than 100,000 per μL).

• Prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT).

Genetics

• Thought to be an autosomal recessive disorder

• G1548C mutation of LCHAD associated with AFLP (14)

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is one of exclusion and is usually made based on laboratory findings, patient symptoms, and clinical exam. Ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans may be suggestive. Liver biopsy may also be helpful. Decisive action is needed to avoid significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Differential Diagnosis

• Severe preeclampsia

• HELLP syndrome

• Hemolytic–uremic syndrome

• Thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura

Clinical Manifestations

• Distinguish from severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome

• Risk for fulminant hepatic failure

• Severe maternal hypoglycemia

• DIC

Treatment

• The definitive treatment of AFLP is delivery.

• Management prior to delivery is dependent on the presence or absence of other related problems:

• Preeclampsia/eclampsia

• Maternal metabolic abnormalities

• Hemostatic disorders

• Renal failure

• Sepsis

• Fetal distress

• Once the patient is stabilized, delivery should be accomplished. Vaginal delivery may be attempted if both the mother and fetus are stable. Otherwise, cesarean section is used if either is unstable or if delivery must be performed expeditiously.

Procedures

Liver transplant may be necessary if patient has extensive liver necrosis.

Counseling

• The risk of recurrence with subsequent pregnancies is uncertain.

• If there is a family history for AFLP, the patient should consider genetic consultation to evaluate for possible LCHAD abnormalities (15).

Complications

• Maternal mortality is 1% to 4% and is often due to

• Cerebral edema

• Gastrointestinal hemorrhage

• Renal failure

• Sepsis

• Fetal mortality is 10% to 20% (7).

• DIC occurs in 75% of cases.

• Postpartum hemorrhage risk is increased.

• After delivery and initial postpartum recovery, expect the liver function to return to normal. There are no long-term sequelae.

Patient Education

Patients should be evaluated for genetic predisposition to LCHAD disorders.

• If patient is in an “at-risk” group with future pregnancies, she should

• Maintain high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet

• Avoid fasting

• Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tetracycline, and valproic acid (16)

• Possible risks to the newborn

• Child should be screened for fatty acid oxidation (FAO) disorder

• Reye syndrome

Concurrent Maternal Hepatic Disease and Pregnancy

In general, severe maternal hepatic disease precludes pregnancy because these patients are usually amenorrheic. Pregnancy does not seem to adversely impact mild to moderate hepatic disease and vice versa.

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is the most common cause of hepatitis in pregnancy. The course of the disease is usually unaffected by pregnancy. Diagnosis and treatment are generally the same as for the nonpregnant patient. Multiple viruses are involved, and while the symptoms and presentation may be similar, the outcomes, complications, and long-term sequelae vary significantly.

Hepatitis A Virus (HAV)

Background

Etiology

• Single-stranded RNA enterovirus

• Usually spread by fecal–oral transmission

• Short incubation period of 4 weeks

Epidemiology

• Endemic in Africa, Asia, and Central America

• Sporadic outbreaks in the United States, usually food borne

Evaluation

History and Physical

• The patient will present with a flu-like illness including

• Malaise and fatigue

• Headache and arthralgias

• Fever

• Pruritus

Physical Findings

• Hepatosplenomegaly

• Dark urine

• Jaundice

Laboratory Tests

• Transaminases are elevated.

• IgM antibodies to hepatitis A virus (HAV) are diagnostic.

Differential Diagnosis

• Hepatitis due to other viruses

• B, C, D, or E

• Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

• Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

• Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)

• Chemical hepatitis

• Jaundice due to other types of hepatic dysfunction

• Increased production of bilirubin

• Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Treatment

Treatment for HAV is supportive as this is usually a self-limited infection. Postexposure prophylaxis with hepatitis immune globulin is effective 80% of the time if given within 2 weeks of exposure. Immunization of pregnant women in endemic areas should be encouraged. There does not appear to be vertical transmission to the fetus. However, if active infection is present at the time of delivery, prophylaxis with immunoglobulin is recommended for the fetus.

Complications

• Hepatic failure is reported but rare.

Patient Education

• Patients should be vaccinated if they live in endemic areas.

• Stress good hand washing.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Background

Etiology

• Double-stranded DNA virus in the core particle

• Long incubation period (up to 180 days)

Epidemiology

• Endemic in Southeast Asia and China.

• In the United States, hepatitis B virus (HBV) is transmitted by contaminated needles, blood products, or direct mucosal contact with contaminated body fluids.

• Chronic carrier state and chronic infection can occur.

Evaluation

History and Physical

The acute infection may be asymptomatic and anicteric. When obtaining a history, look for risk factors that include

• Intravenous (IV) drug use

• Multiple sexual partners

• History of multiple blood transfusions

• Partner with HBV

• History of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Physical Exam

Physical Exam may reveal

• Urticarial rash.

• Arthralgias and arthritis.

• Myalgias.

• Hepatomegaly and/or right upper quadrant tenderness.

• Jaundice is less common.

Laboratory Tests

• All pregnant patients should be screened for HBV infection.

• Transaminases are elevated with acute infection.

• Tests for the presence of antigen/antibodies to the following:

• Viral surface components

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

• Core DNA

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg)

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg)

• Enzymatic components of viral core (“C” antigens)

Usually present with acute infection

Usually present with acute infection

Indicative of high infectivity if present

Indicative of high infectivity if present

• E antigen

HBeAg is a marker for infectivity.

HBeAg is a marker for infectivity.

• Specific antigens and antibodies associated with hepatitis B infection vary over the course of the disease.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

• Hepatitis due to other viruses

• A, C, D, or E

• CMV

• HSV

• EBV

• Chemical hepatitis

• Jaundice due to other types of hepatic dysfunction

• Increased production of bilirubin

• Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree