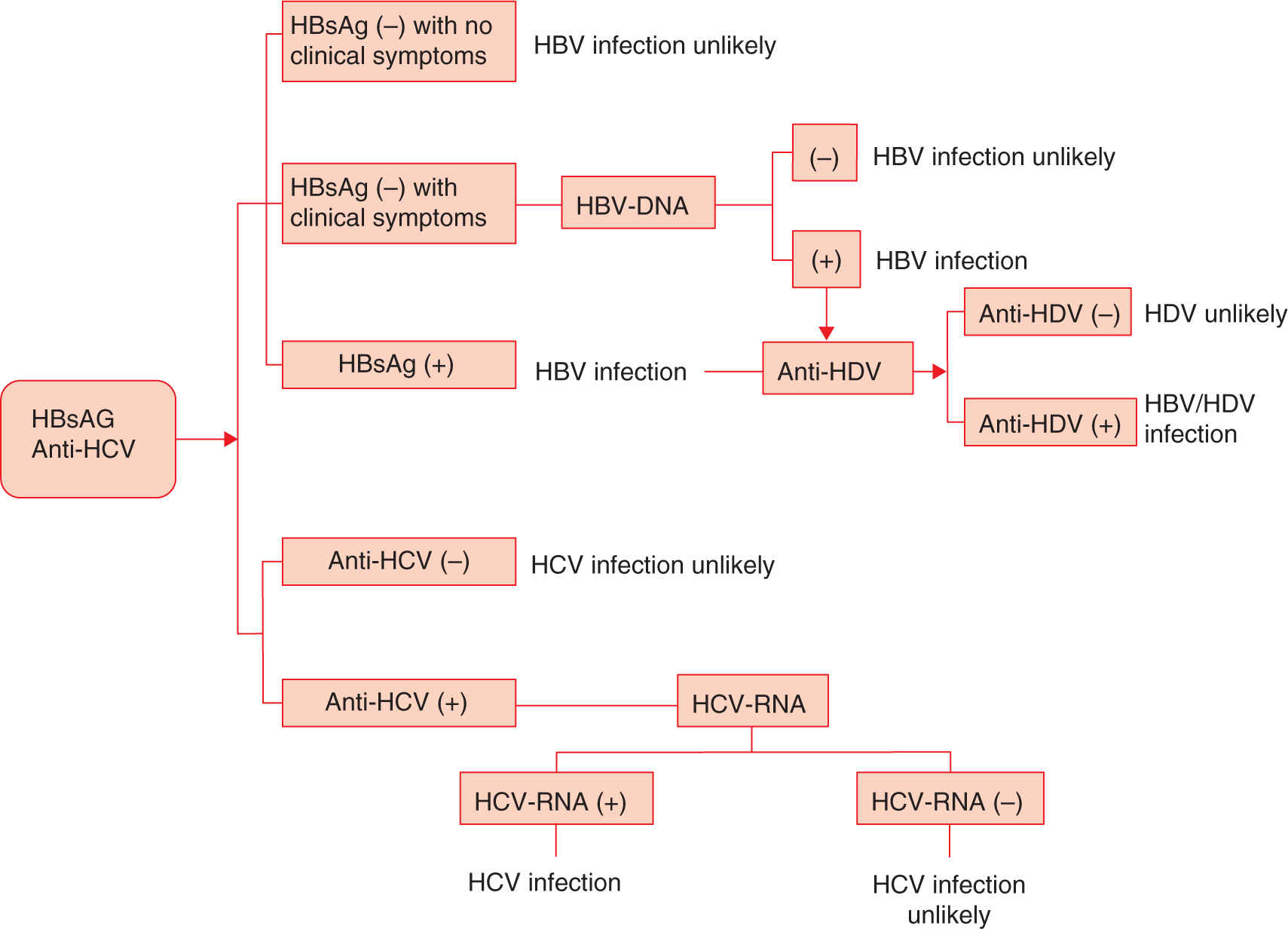

FIGURE 19-1. Decision algorithm in the diagnosis of acute hepatitis.

Acute hepatitis A

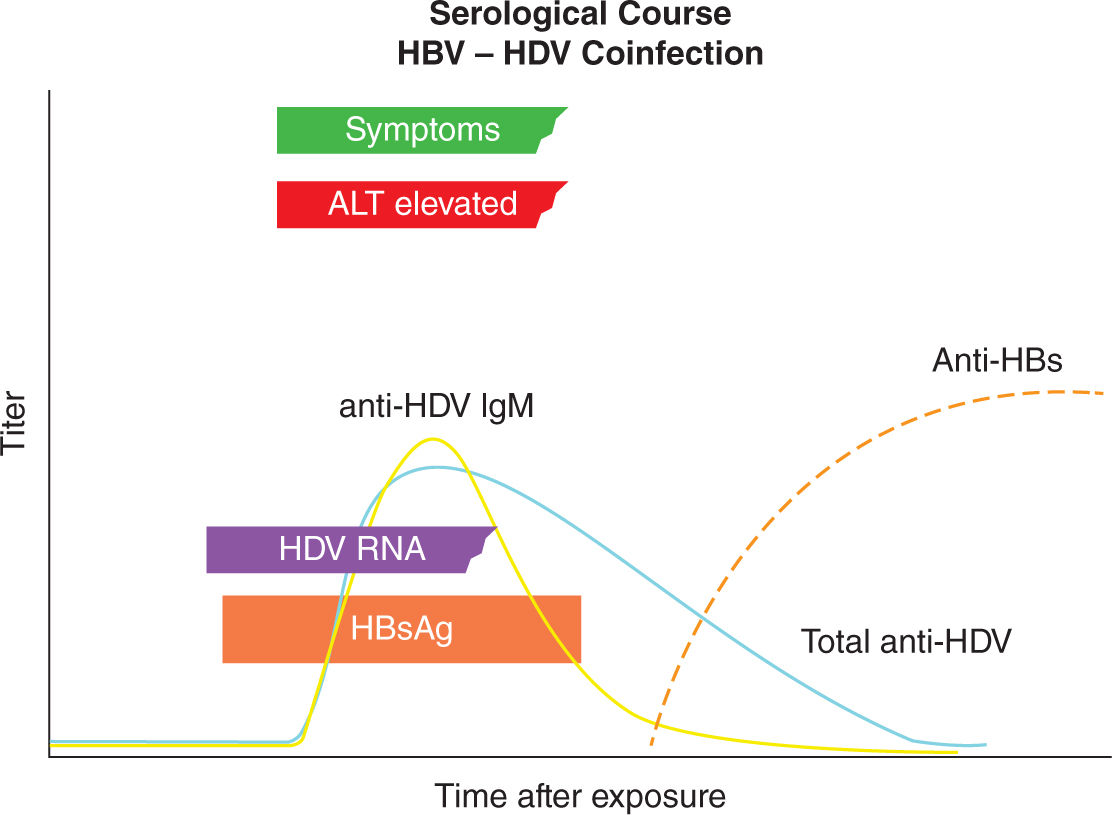

In nonvaccinated pregnant women with acute HAV infection, the clinical presentation usually ensues after an incubation period of 2 to 6 weeks. Acute HAV infections usually result in self-limited illnesses, which last 1 to 2 weeks. Symptoms usually begin abruptly with fever, nausea, and vomiting. Demonstrating anti-HAV of the IgM class makes the diagnosis of acute HAV infection. After acute illness, anti-HAV of the IgG class becomes predominant in patient serum (Figure 19-2) 38

FIGURE 19-2. Serology marker profile for diagnosis acute HAV infection. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

There is no evidence that pregnancy alters the course of HAV infection or that HAV infection affects pregnancy outcome in developed countries. However, a higher incidence of fulminant HAV infections has been reported in developing countries, although the reason is uncertain. Concurrent malnutrition may play a role.

Acute Hepatitis B

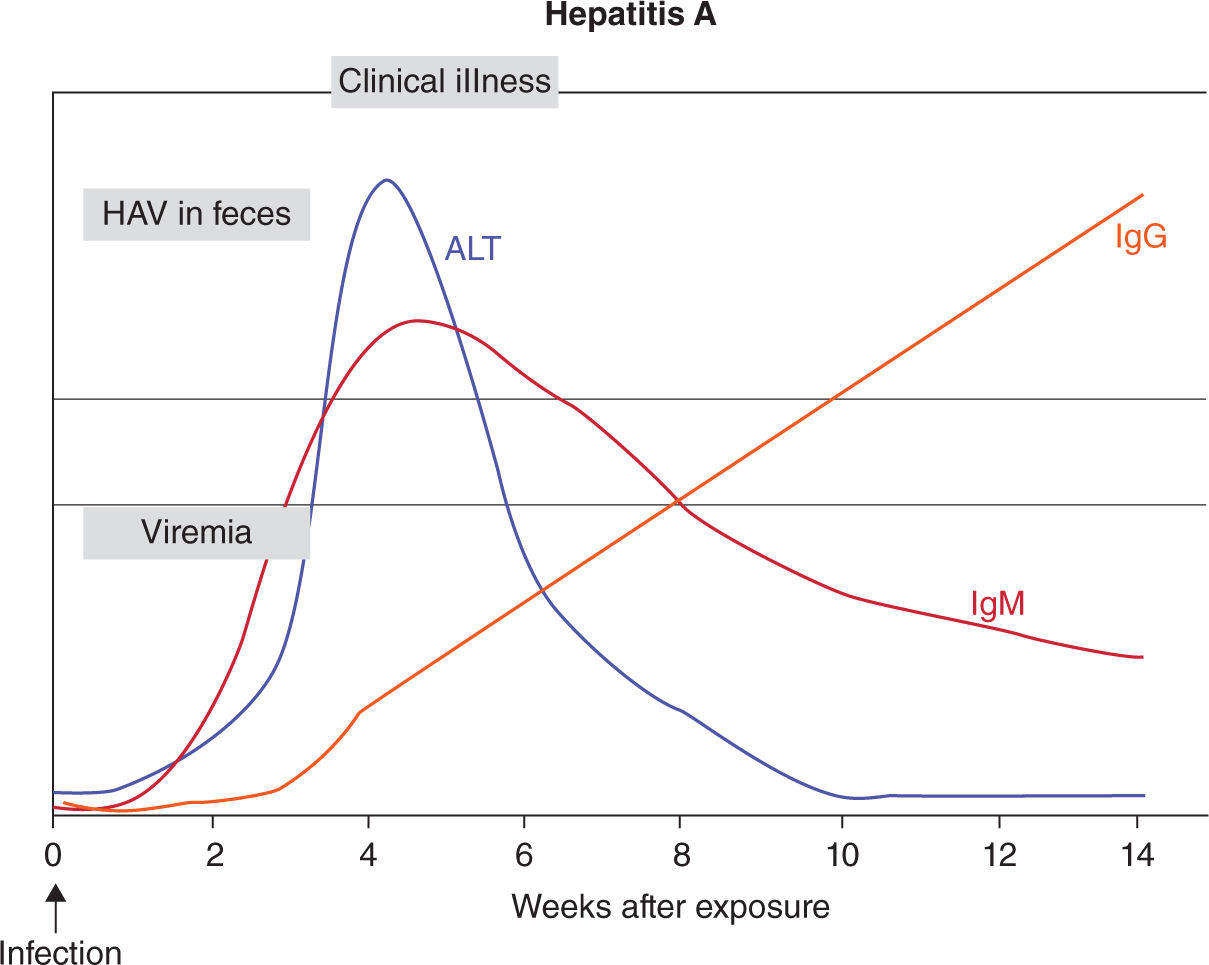

Acute HBV infection typically occurs after parenteral exposure to contaminated blood or sexual contact with an infected partner. The incubation period varies between 50 and 180 days. Confirmation of HBV infection depends on the presence of specific immunologic markers. HBsAg and HBeAg appear early in the disease and usually before the onset of clinical symptoms. Infectivity of HBV is highest during this early phase with the presence of HBeAg in serum before appearance of jaundice. Anti-HBc appears during the midphase of the clinical course, initially of IgM class with posterior development of the IgG antibody. The combination of a detectable HbsAg with an anti-HBc IgM makes the diagnosis of acute hepatitis B. Later, antibodies against the e antigen and the surface antigen will develop (Figure 19-3). Cases of severe acute HBV infection in the third trimester of pregnancy present a diagnostic dilemma and must be differentiated from pregnancy-related liver diseases such as intrahepatic cholestasis and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. In an otherwise healthy mother, acute HBV infection does not increase maternal mortality. However, a higher incidence of prematurity and low fetal birth weights has been reported.9

FIGURE 19-3. Serology marker profile for diagnosis and the typical course of acute HBV infection. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

Acute Hepatitis C

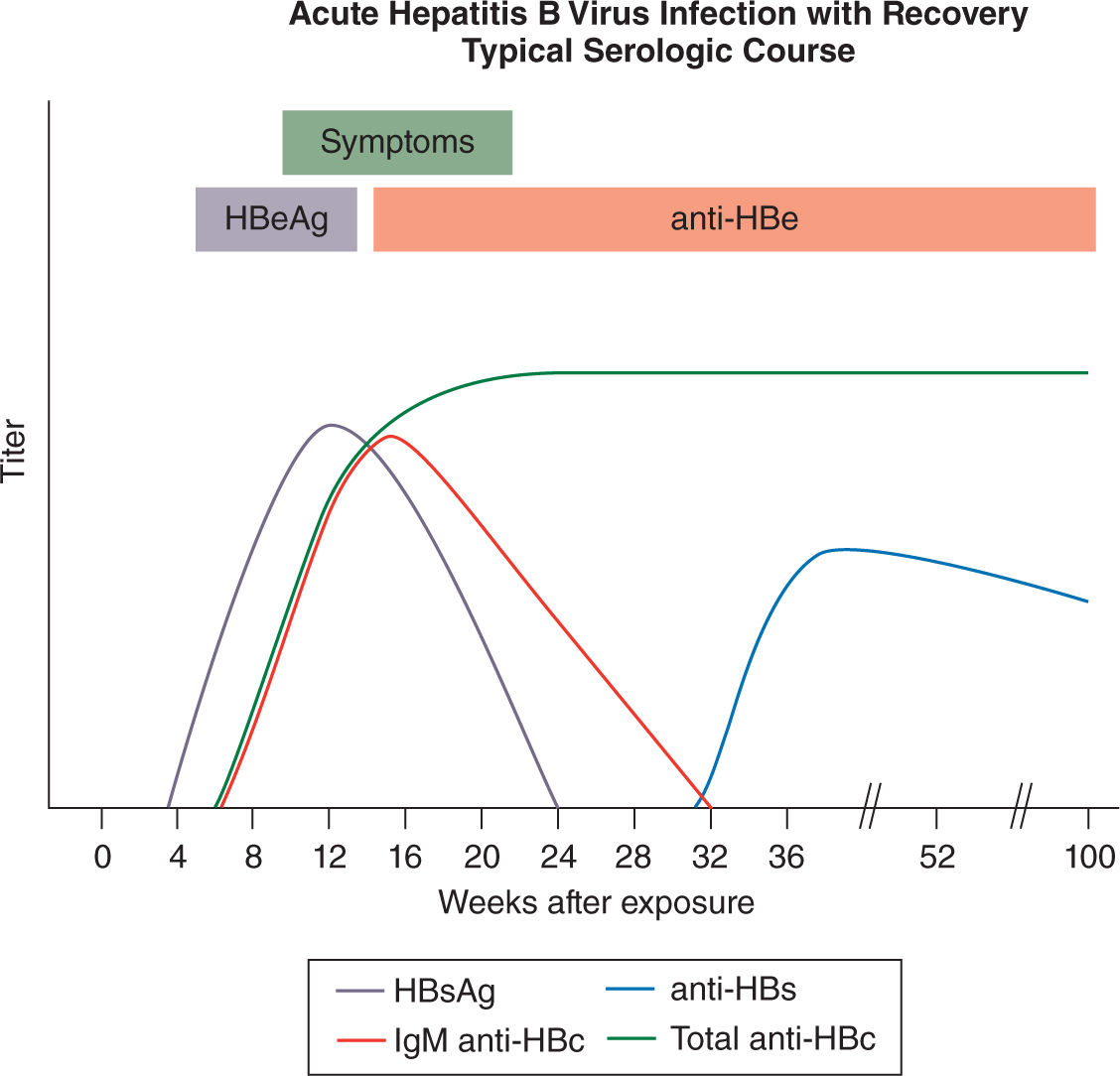

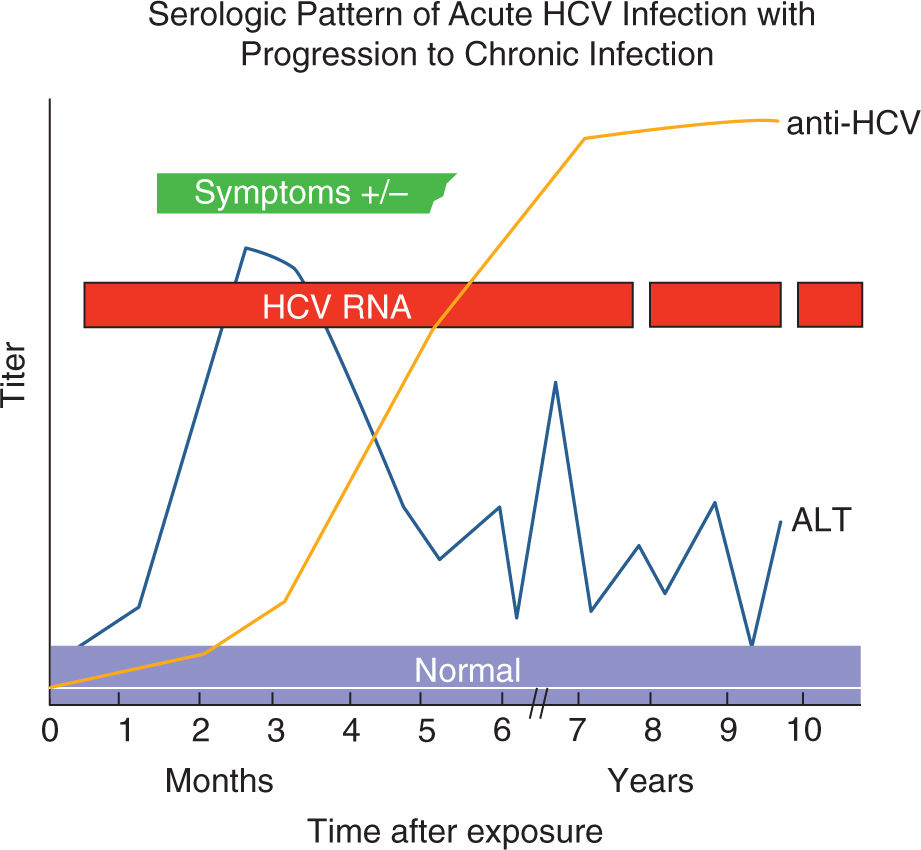

Most acute HCV infections are asymptomatic or cause mild nonspecific symptoms such as malaise and anorexia, while only 10% to 20% results in overt icteric hepatitis.39 The diagnosis of acute HCV infection can be confirmed by detecting either anti-HCV antibody (may be absent in 30% of acute infections) or HCV RNA in maternal serum (Figure 19-4).40

FIGURE 19-4. Serologic pattern of acute HCV infection with recovery. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

It is not clear whether pregnancy alters the outcome of acute HCV infection, but it is conceivable that the immunomodulation of pregnancy could favor viral persistence rather than clearance. At the same time, it is not known if acute infections during pregnancy are more likely to result in perinatal transmission or adverse pregnancy outcomes than chronic infections. Premature delivery was described in three of eight reported cases of acute HCV infection, but this is likely a publication bias.41

Acute Hepatitis D

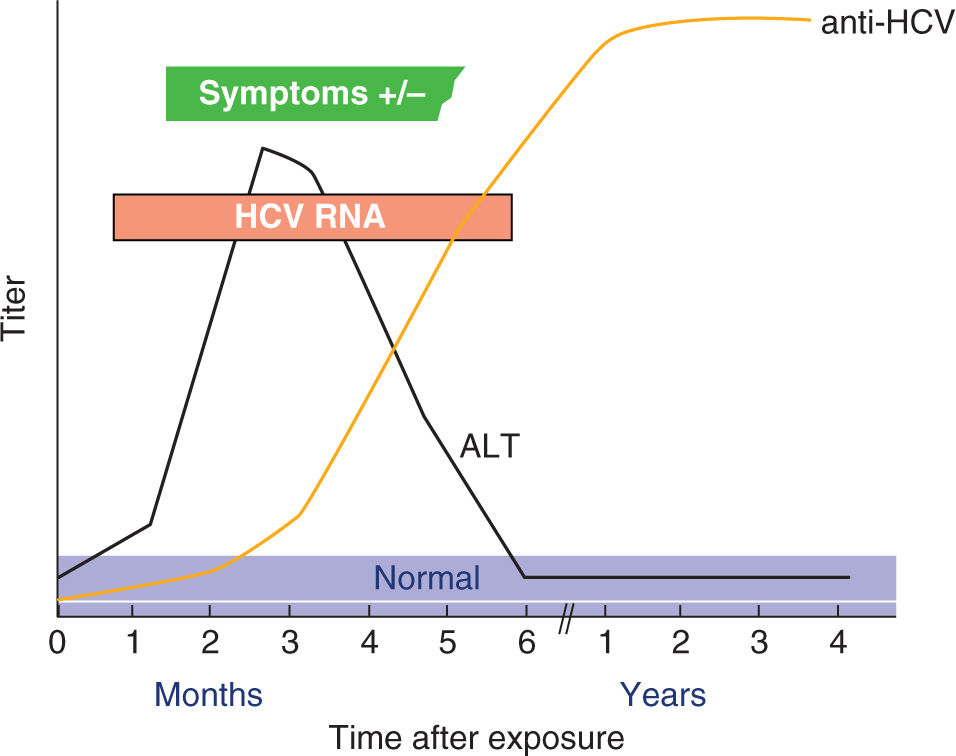

The clinical presentation of acute hepatitis D in pregnant women is similar to nonpregnant adults and depends on whether HDV and HBV infections occurred as a coinfection or superinfection. In coinfections, the fate of acute HDV is determined by the host response to HBV, which in more than 95% of adults results in viral clearance with low risk for development of chronic HDV infection. However, acute coinfection may be associated with more severe acute hepatitis and higher mortality than that because of acute HBV alone. In contrast, HDV superinfection in an HBV chronic carrier usually results in chronic HDV infection and development of severe chronic liver disease. Superinfection can also present as acute hepatitis in a previously undiagnosed carrier of HBsAg and is often misdiagnosed as acute HBV or as worsening liver disease because of chronic HBV.

HBsAg positive individuals should be tested for anti-HDV antibodies. Acute HDV infection is usually diagnosed by the presence of anti-HDV IgM and confirmed by the detection HDV RNA in serum. In most individuals with HBV-HDV coinfection, both anti-HDV IgM and anti-HDV IgG are detectable during the course of the infection. However, in about 15% of patients, the only evidence of HDV infection may be the detection of either anti-HDV IgM alone during the early acute period of illness or anti-HDV IgG alone during convalescence. Anti-HDV generally declines to under detectable levels after the infection resolves, and there is no serologic marker that persists to indicate that the patient was ever infected with HDV. HDV RNA can be detected in serum in only about 25% of patients with HBV-HDV coinfection. HDV RNA generally disappears as HBsAg disappears and most patients do not develop chronic infections (Figure 19-5).42

FIGURE 19-5. Diagnostic markers of hepatitis DDV (delta virus) (HDV) infection and profile of hepatitis B virus (HBV)/HDV coinfection. ALT indicates alanine transaminase; anti-HDV IgG, HDV immunoglobulin G antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen. Adapted with permission from Hughes SA, Wedemeyer H, Harrison PM. Hepatitis delta virus, Lancet. 2011; 378(9785):73–85.42

Acute Hepatitis E

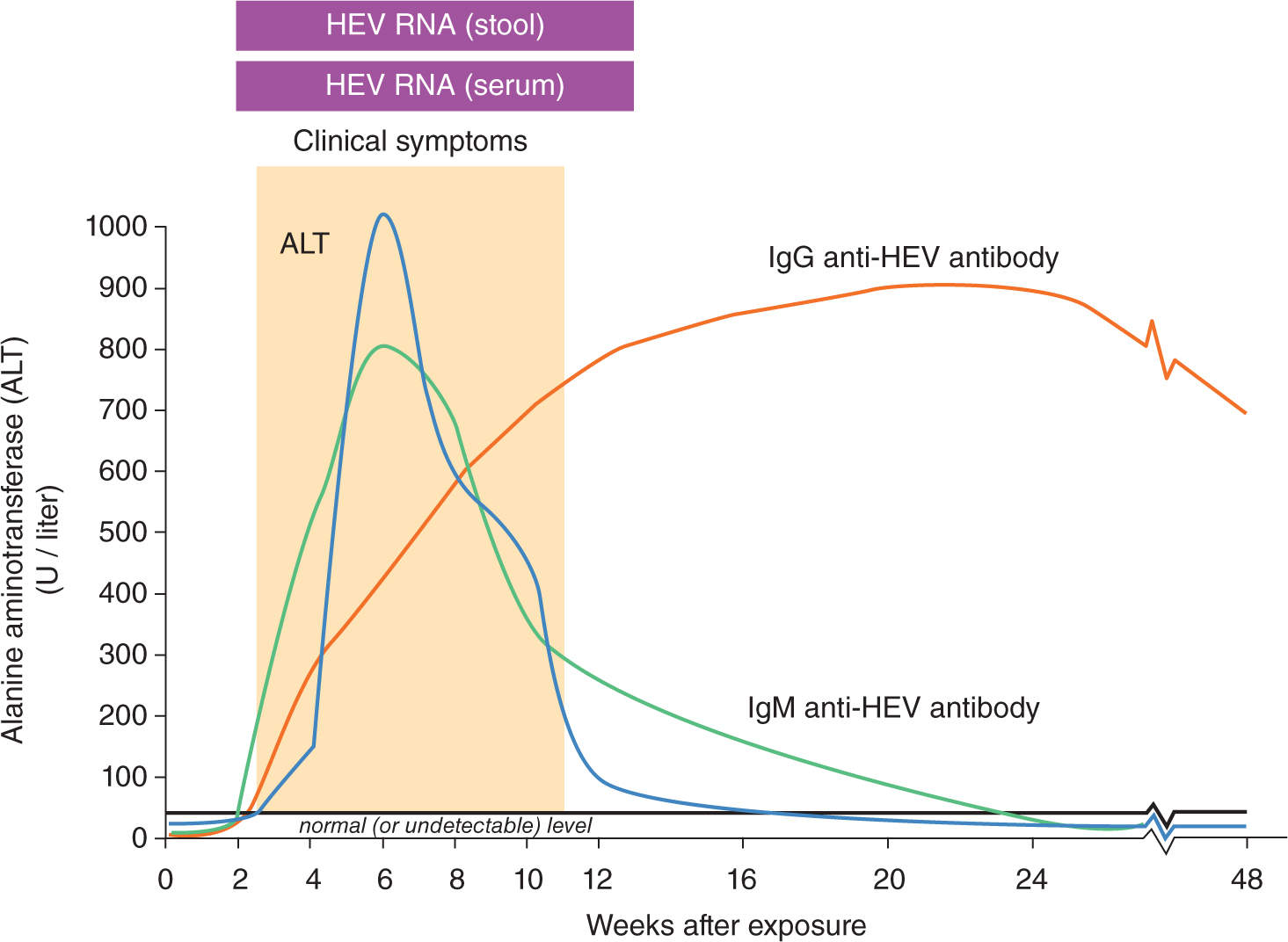

Acute HEV infection is characterized by symptoms of acute hepatitis such as fever, anorexia, vomiting, and jaundice, with onset several weeks after initial exposure. The incubation period is between 2 and 6 weeks and most infections resolve spontaneously, but in some patients, the infection may progress to fulminant hepatitis. The onset of clinical symptoms coincides with a sharp rise in serum ALT levels. Symptoms may persist for a few weeks and ALT levels return to normal during convalescence. HEV RNA may be detected in both serum and stool early in the course of infection, but serum viremia may be difficult to detect by the time cases come to clinical attention. Anti-HEV IgM titers increase rapidly and then wane over the weeks following infection, while anti-HEV IgG antibody titers continue to rise more gradually during the convalescent period and detectable anti-HEV IgG may persist for months to years (Figure 19-6).

FIGURE 19-6. Serology marker profile for diagnosis and typical course of acute HEV infection. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

In developing countries, epidemics of acute hepatitis E are mainly caused by HEV1 and HEV2 and associated with mortality rates between 0.5% and 4%.19 One intriguing characteristic is that acute HEV infection is often lethal in pregnant women with mortality rates of up to 20% to 25% observed only in HEV1 infections. Increased frequencies of obstetric complications and stillbirths have also been reported.43 Maternal mortality occurs largely in the third trimester and is caused by FHF.20,44 Poor neonatal outcomes is also common in mothers with HEV infection and can be explained to a large extent by preterm delivery.45

Diagnosis of HEV infection relies on detection of anti-HEV IgM and IgG, and/or HEV RNA in serum. The presence of anti-HEV IgM indicates a recent infection, while anti-HEV IgG indicates past exposure.

Chronic Hepatitis

In some patients, chronic infections persist and patients become carriers of the infecting virus(es). Most chronic hepatitis carriers remain asymptomatic and are not aware of their condition; however, up to one-third subsequently develop chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Once cirrhosis ensues, patients have the typical signs of end-stage liver disease, such as jaundice, muscle wasting, ascites, portal hypertension, coagulopathy, spider angioma, palmar erythema, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Figure 19-7 depicts a suggested algorithm for the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis.

FIGURE 19-7. Decision algorithm in the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis.

Chronic Hepatitis B

In the United States, routine universal prenatal screening for HBV identifies women who are positive for HBsAg and consequently chronic carriers of HBV infection (a chronic carrier is defined as an individual in whom HbsAg is detectable for 6 months or longer). Thus, pregnancy provides an opportunity to deliver appropriate medical care to infected women.

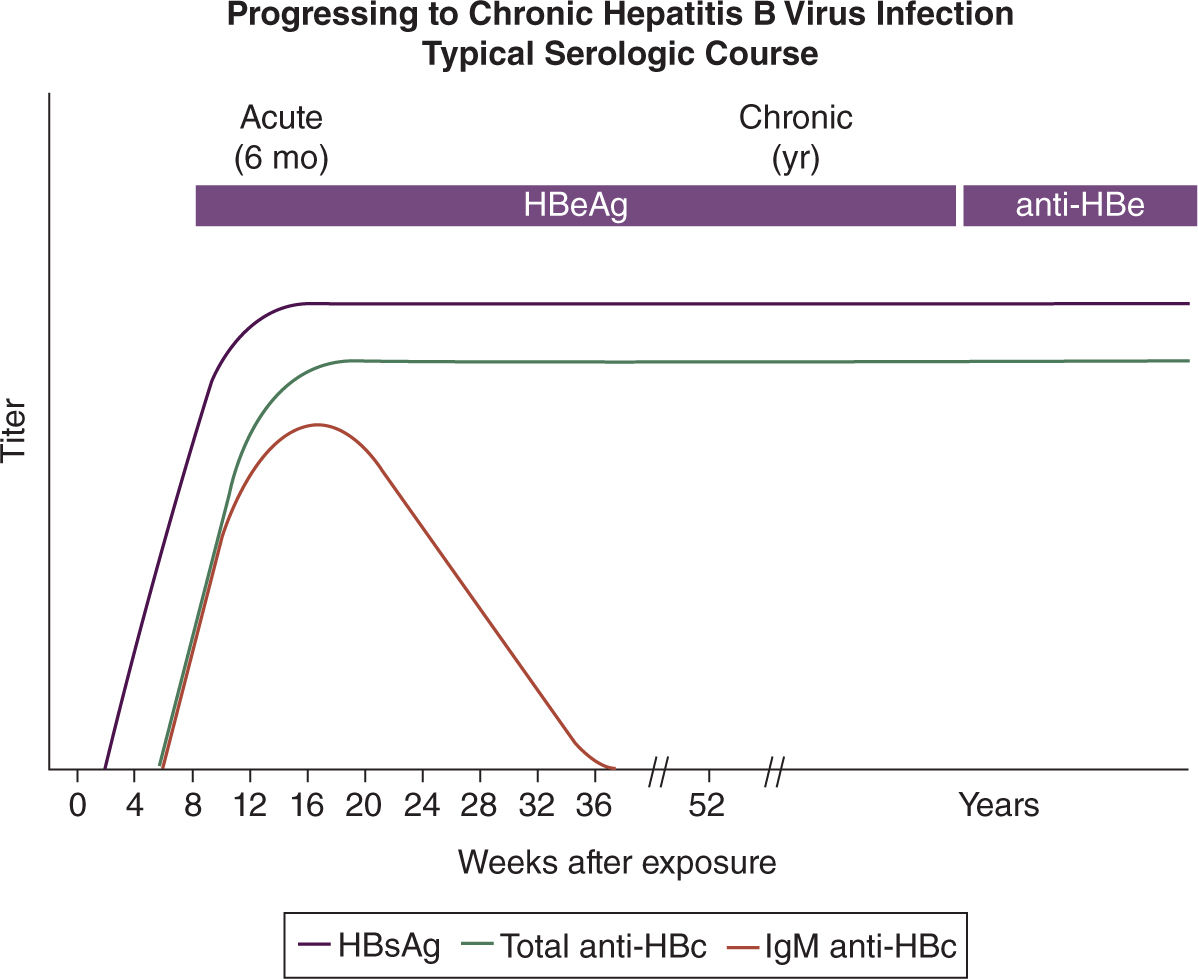

Most patients with chronic hepatitis B during pregnancy are asymptomatic. Diagnosis of chronic HBV infection or chronic carrier state of HBV depends on the persistence of HBsAg and absence of anti-HBs IgG antibodies, which is the protective antibody that defines immunity. All HBV carriers have IgG antibodies to HBcAg (anti-HBc) and some have antibodies to HBeAg (anti-HBe). Anti-HBc is present only in the context of natural HBV infection and is not a protective antibody (Figure 19-3). Chronic HBV infected patients with high concentrations of both HBsAg and HBeAg are more likely to be transmitters of the disease than are those who have solely HBsAg in their blood (Figure 19-8).24

FIGURE 19-8. Serology marker profile for diagnosis and the typical progression course of chronic HBV infection. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

The high levels of corticosteroids and modulation of cytokines involved in the immune response during pregnancy can result in increased viremia. These changes often lead to clinically insignificant fluctuations in liver function tests late in pregnancy and the postpartum.46 Case reports and retrospective studies indicate adverse events including hepatitis exacerbation and even FHF that required antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation during pregnancy.47,48

Limited data have correlated maternal chronic HBV infection with a higher incidence of gestational diabetes and antepartum hemorrhage.49 Patients with advanced cirrhosis who achieve pregnancy may experience poor perinatal outcomes.50

The postpartum period is considered a vulnerable time for exacerbations of HBV infection. This might suggest a reactivation of the immune system after delivery and HBsAg-positive mothers should be monitored closely for evidence of liver decompensation in the postpartum period.51

Data are conflicting regarding fetal outcomes of maternal chronic HBV infection. A large retrospective study comparing HBsAg-positive mothers to HBsAg-negative controls showed no differences in gestational age at delivery, birth weight, neonatal jaundice, congenital anomalies, incidence of prematurity, or perinatal mortality.52 Conversely, recent studies suggest that maternal chronic HBV infection was associated with higher rates of preterm labor, perinatal mortality, congenital malformations, and low birth weight.53,54 Other studies have shown that the strength of association between maternal chronic HBV infection and adverse fetal outcome is still unclear.55

Chronic Hepatitis C

Similar to HBV infection, most patients with chronic HCV infection are asymptomatic or have mild fatigue and are identified incidentally in the course of evaluation for unexplained ALT elevation or after blood donation. The effect of pregnancy on chronic HCV infection appears to be minimal. A modest increase (0.2-0.8 log IU/mL) in average viral load concurrent with declines in ALT levels has been documented in women with chronic HCV infection in pregnancy. Because the elevation of ALT in HCV infection is thought to be because of immune-mediated hepatocyte injury rather than toxicity from viral replication per se, it is speculated that these viral load and ALT changes in pregnancy reflects suppression of cellular immunity.56 In postpartum period, a sharp decrease in viremia 1 to 3 months after delivery has been reported.57,58

The diagnosis of chronic HCV infection can be confirmed by detection of both the anti-HCV antibody and HCV RNA in maternal serum (chronic infection is defined as persistence of the virus for longer than 6 months). Detection of a positive antibody with negative viremia is consistent with an old nonactive infection or a false-positive antibody result.26

The effect of chronic HCV infection on pregnancy outcomes is not clear. Small noncontrolled studies conducted after discovery of HCV did not describe any adverse obstetric or fetal outcomes.59 Other studies have reported increased rates of cesarean delivery which is probably related to refrainment of obstetricians to use fetal scalp electrodes for reassurance of fetal status.59,60 However, population-based studies have uncovered independent associations of maternal chronic HCV infection with gestational diabetes,33,61 preterm delivery,55 low birth weight, small for gestational age,61 and cholestasis of pregnancy.62 The increased risk of gestational diabetes among HCV-infected pregnant women is plausible given that chronic HCV infection increases the risk of insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in nonpregnant persons.63 Mechanisms for prematurity and small for gestational age outcomes in HCV are not known.64 Figure 19-9 shows the serologic conversion and viral load changes after infection with hepatitis C.

FIGURE 19-9. Serologic marker pattern for diagnosis of HCV infection and progression to chronic HCV Infection. Adapted with permission from CDC website.

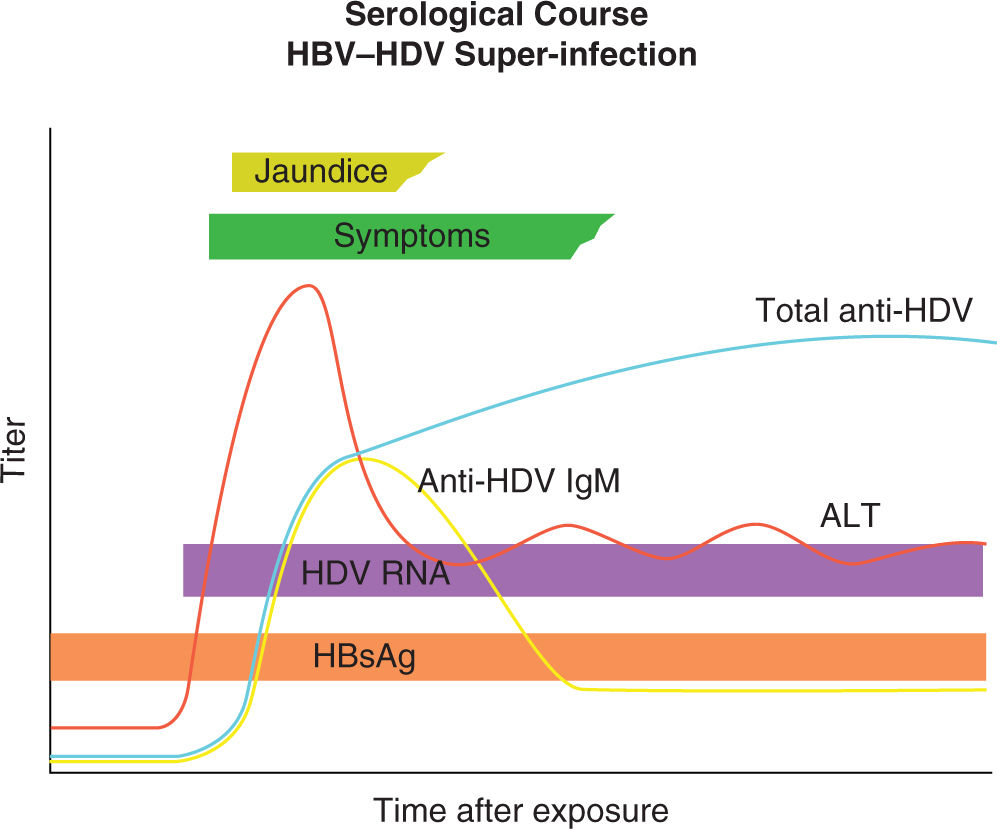

Chronic Hepatitis D

Chronic HDV infection usually follows a superinfection of an individual with chronic HBN infection. In patients who are superinfected with HDV, several characteristic serologic features generally occur. HBsAg positivity precedes the detection of HDV RNA and the titer of HBsAg declines at the time HDV RNA appears in patient serum. High titers of both IgM and IgG anti-HDV are detectable, which persist indefinitely (Figure 19-10). In a minority of superinfections, the replication of HDV stops and the natural history of the disease is that of the underlying HBV; however, the residual liver disease might be advanced.42

FIGURE 19-10. Diagnostic markers of hepatitis HDV (delta virus) infection and profile of hepatitis B virus (HBV)/HDV superinfection. ALT indicates alanine transaminase; anti-HDV IgG, HDV immunoglobulin G antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen. Adapted with permission from Hughes SA, Wedemeyer H, Harrison PM. Hepatitis delta virus, Lancet. 2011; 378(9785):73–85.42

MATERNAL-FETAL TRANSMISSION

Hepatitis A

There is no evidence of mother-to-infant transmission of HAV during pregnant or at delivery, whether at term or preterm. Also, there is no evidence that HAV infection causes birth defects.65,66

Hepatitis B

Maternal-fetal transmission is a common mode of HBV infection worldwide.9 HBV infection in newborns is defined as HBsAg positivity 6 months after birth. The presence of anti-HBe and anti-HBc in infant sera does not indicate perinatal transmission of HBV infection, as these antibodies can cross the placenta and remain in infant sera till 12 and 24 months of age, respectively. Transmission of HBV from mother to her neonate can occur during pregnancy via transplacental transfer, at delivery through exposure of infant’s mucosal membranes to maternal secretions in the birth canal, and in the postpartum period as a result of close contact between mother and baby.67

Acute HBV infection during pregnancy imposes a significant risk for perinatal transmission of HBV to the newborn. The frequency of prenatal transmission depends on the time during gestation that maternal infection occurs. When it occurs in first trimester, up to 10% of neonates will be seropositive for HBsAg. In women acutely infected in the third trimester, 80% to 90% of offsprings will be infected.68

Chronic HBV infection is the main contributor to perinatal transmission of HBV infection to neonates as most pregnant women are not aware of their HBV infection status. In the absence of neonatal immunoprophylaxis, perinatal transmission depends on maternal HBsAg and HBeAg seropositivity. In women who are seropositive for HBsAg alone, the frequency of transmission is 10% to 20%, while it increases to approximately 90% in women who are seropositive for both HBsAg and HbeAg. Perinatal transmission can also occur in women with occult HBV infection, who are HBsAg negative but positive for HBV DNA. Case reports have suggested that occult HBV infection in pregnancy might be a significant problem in populations with a high prevalence of HBV infection.69

The majority (85%-95%) of cases of perinatal transmission occurs as a consequence of intrapartum infant exposure to infected blood and genital secretions. The risk of transmission is 10% to 40% in HBeAg-negative/anti-HBe-negative mothers and less than 12% for HBeAg-negative/anti-HBe-positive mothers.35 The absence of HBeAg expression is associated with lower levels of viral replication and consequently a lower risk of intrauterine transmission.70 High HBV DNA levels in maternal serum is a risk factor for intrauterine infection and correlate with HBV DNA levels and HBsAg titers in neonatal cord blood.71

Breastfeeding is not contraindicated in HBV positive mothers.72 The risk of transmission through amniocentesis (if required during pregnancy) appears to be low. In seropositive women with HBsAg, no significant difference in the rate of neonatal HBV infection was noted between women who underwent second-trimester amniocentesis and those who did not have the procedure done.73 Administration of steroids for fetal lung maturity is considered safe and there is no evidence that the small dose of steroids given for fetal lung maturity will have a negative impact on perinatal transmission of HVB infection or on viral replication. Theoretically, the risk of perinatal transmission increases with prolonged rupture of fetal membranes and use of fetal scalp electrodes.

Hepatitis C

Perinatal transmission of HCV is between 4% and 6%. The risk of perinatal transmission is two- to threefold higher for mothers with HIV/HCV coinfection.72

The exact timing and the mechanism of perinatal transmission of HCV infection are unknown. Among children acquiring the infection from their mothers, only a few have been found to be HCV RNA positive in the first few days of life. The majority of children born to mothers with hepatitis C have HCV RNA detectable levels several weeks after delivery suggesting that late intrauterine or intrapartum transmission is the predominant route of mother to child transmission of HCV. It is estimated that 31% of infants acquire HCV infection during the intrauterine period (transplacental transmission) and 40% to 50% of perinatal transmissions occur in the peripartum period, whereas postpartum transmission is rare.74–76

In HCV-infected women undergoing vaginal delivery, viral loads were higher among transmitters than nontransmitters.77 Maternal disease severity among HCV RNA positive mothers and elevated pre-pregnancy ALT levels were also associated with an increased risk of perinatal transmission.78 Women with viral loads above 107 IU/mL appeared to be at particularly high risk of transmission (odds ratio [OR], 10.2; p = 0.03). Nevertheless, no lower threshold of viremia below which transmission does not occur has been determined.79–82

Maternal HIV coinfection has been consistently associated with an increased risk of perinatal transmission of HCV (up to 14%-16%).96

Neonates born to mothers who sustained a vaginal or perineal laceration have sixfold higher risks of becoming HCV infected.77 Second twins delivered vaginally and prolonged rupture of membranes also increase the risk of perinatal transmission.83 Internal fetal monitoring (fetal scalp electrodes) similarly was associated with increased transmission with an OR of 6.7 (95% CI, 1.1-35.9).84

Data on the effect of amniocentesis on mother-to-fetus transmission of HCV are limited. Although amniocentesis may contribute to the risk of perinatal transmission, a prospective study of 22 HCV-positive women who underwent mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis found no cases of viral transmission. In only a single case was the virus identified unamniotic fluid (with an anterior placenta, suggesting that the placenta should be avoided during the procedure).85

Although HCV RNA has been detected in breast milk and colostrum, breastfeeding does not appear to be a primary route of maternal-infant HCV transmission.68 The quantity of virions in these bodily fluids is insufficient to result in infection. Mothers infected with HCV are encouraged to breastfeed in the absence of other contraindications, such as HIV coinfection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention propose temporary interruption of breastfeeding when the mother has cracked, bleeding, or traumatized nipples, which could increase exposure of the infant to HCV.86

Hepatitis D

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree