Heart murmurs are very common in infants and young children. Most are ‘functional’ or ‘innocent’ and are not associated with structural abnormalities. It is important to learn to distinguish these from murmurs associated with cardiac disease. Once a structural lesion has been excluded, the benign nature of the murmur should be discussed with the parents. It is helpful to describe it as a simple ‘noise’ which itself does not indicate a cardiac defect. Innocent flow murmurs may be more apparent at times of illness or fever.

Defects Causing a Left-To-Right Shunt

These are the commonest defects. If large, a considerable volume of blood is shunted, causing hypertrophy, ventricular dilatation and congestive cardiac failure. They usually present as breathlessness. The child is not cyanosed.

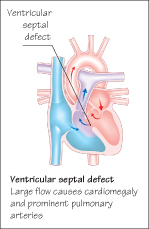

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

This is the commonest congenital lesion. If the VSD is small the child may be asymptomatic but a large shunt causes breathlessness on feeding and crying, poor growth and recurrent chest infections. A harsh, rasping, pansystolic murmur is heard at the lower left sternal border and in large defects the heart is enlarged, a thrill is present and the murmur radiates over the whole chest. There may be signs of heart failure. Loudness of the murmur is not related to the size of the shunt. In large defects cardiomegaly and large pulmonary arteries are seen on the chest radiograph and biventricular hypertrophy on ECG. Echocardiography confirms the diagnosis.

Prevention of endocarditis is important. Small muscular defects usually close spontaneously. Large membranous defects with cardiac failure are initially managed medically, but surgical treatment may be required. If uncorrected, the increased pulmonary blood flow can lead to pulmonary hypertension which eventually leads to reversal of the shunt and intractable cyanosis. (Eisenmenger’s syndrome).

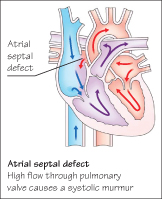

Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

As the murmur is soft, it may not be detected until later childhood. The systolic murmur is heard in the second left interspace, and is due to high flow across the normal pulmonary valve and not due to flow across the ASD itself. The second heart sound is widely split and ‘fixed’ (does not vary with respiration). The child may experience breathlessness, tiredness on exertion or recurrent chest infections. If the defect is moderate or large, closure is carried out either by open heart surgery or using a cardiac catheter. The outcome is usually good. If untreated, cardiac arrhythmias can develop in early adulthood.

Obstructive Lesions

Obstructive lesions can occur at the pulmonary and aortic valves and along the aorta. The chamber of the heart proximal to the lesion hypertrophies, and heart failure may develop.

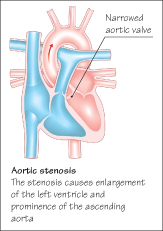

Aortic Stenosis

Aortic stenosis is usually identified at routine examination, but some children may experience syncope or dizziness on exertion. The systolic ejection murmur is heard at the right upper sternal border and radiates to the neck. It may be preceded by an ejection click and the aortic second sound is soft and delayed. The peripheral pulse is of small volume and blood pressure may be low. A thrill may be palpable at the lower left sternal border and over the carotid arteries.

Chest radiography may show a prominent left ventricle and ascending aorta. Left ventricular hypertrophy is found on ECG. Echocardiography can evaluate the exact site and severity of the obstruction. Severe stenosis is relieved by balloon valvuloplasty—a catheter is passed from the femoral artery and a balloon inflated to widen the stenosis. If unsuccessful, open heart surgery is required. The Ross procedure involves replacing the damaged aortic valve with the patient’s own pulmonary valve, and then fitting a replacement pulmonary valve. Children with aortic stenosis are at risk for sudden death and so this is one defect in which strenuous activity and competitive sports should be avoided.

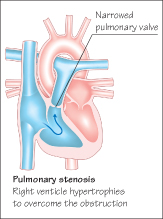

Pulmonary Stenosis

The pulmonary valve is narrowed and the right ventricle hypertrophied. A short ejection systolic murmur is heard over the upper left anterior chest and is conducted to the back. It is usually preceded by an ejection click. With mild stenosis there are usually no symptoms. In severe stenosis a systolic thrill is palpable in the pulmonary area. On chest radiograph dilatation of the pulmonary artery is seen beyond the stenosis, and if severe an enlarged right atrium and ventricle. The extent of the stenosis can be demonstrated by echocardiography and cardiac catheterization. If severe, balloon valvuloplasty is performed. Surgery is generally successful.

Prophylaxis for Infective Endocarditis

Any child with significant congenital heart disease is at risk for developing infective endocarditis, particularly if there is a high velocity shunt or abnormal valves. It is important to reduce the risk of bacterial endocarditis by maintaining healthy teeth and gums, but antibiotic prophylaxis for dental or clean surgery is no longer recommended. Body piercing is not advisable.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>