Chapter 436 Heart Failure

Heart failure occurs when the heart cannot deliver adequate cardiac output to meet the metabolic needs of the body. In the early stages of heart failure, various compensatory mechanisms are evoked to maintain normal metabolic function. When these mechanisms become ineffective, increasingly severe clinical manifestations result (Chapter 64).

Pathophysiology

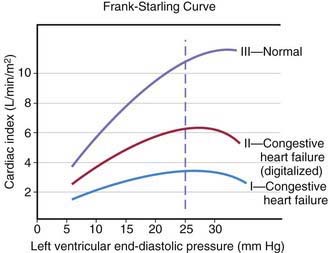

The heart can be viewed as a pump with an output proportional to its filling volume and inversely proportional to the resistance against which it pumps. As ventricular end-diastolic volume increases, a healthy heart increases cardiac output until a maximum is reached and cardiac output can no longer be augmented (the Frank-Starling principle; Fig. 436-1). The increased stroke volume obtained in this manner is due to stretching of myocardial fibers, but it also results in increased wall tension, which elevates myocardial oxygen consumption. Hearts working under various types of stress function along different Frank-Starling curves. Cardiac muscle with compromised intrinsic contractility requires a greater degree of dilatation to produce increased stroke volume and does not achieve the same maximal cardiac output as normal myocardium does. If a cardiac chamber is already dilated because of a lesion causing increased preload (e.g., a left-to-right shunt or valvular insufficiency), there is little room for further dilatation as a means of augmenting cardiac output. The presence of lesions that result in increased afterload to the ventricle (aortic or pulmonic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta) decreases cardiac performance, thereby resulting in a depressed Frank-Starling relationship. The ability of an immature heart to increase cardiac output in response to increased preload is less than that of a mature heart. Thus, premature infants are more compromised by a left-to-right shunt than full-term infants are.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of heart failure depend on the degree of the child’s cardiac reserve. A critically ill infant or child who has exhausted the compensatory mechanisms to the point that cardiac output is no longer sufficient to meet the basal metabolic needs of the body will be symptomatic at rest. Other patients may be comfortable when quiet but are incapable of increasing cardiac output in response to even mild activity without experiencing significant symptoms. Conversely, it may take rather vigorous exercise to compromise cardiac function in children who have less severe heart disease. A thorough history is extremely important in making the diagnosis of heart failure and in evaluating the possible causes. Parents who observe their child on a daily basis may not recognize subtle changes that have occurred over the course of days or weeks. Gradually worsening perfusion or increasing respiratory effort may not be recognized as an abnormal finding. Edema may be passed off as normal weight gain, and exercise intolerance as lack of interest in an activity. The history of a young infant should also focus on feeding (Chapter 416). An infant with heart failure often takes less volume per feeding, becomes dyspneic while sucking, and may perspire profusely. Eliciting a history of fatigue in an older child requires detailed questions about activity level and its course over several months.

In infants, heart failure may be difficult to distinguish from other causes of respiratory distress. Prominent manifestations include tachypnea, feeding difficulties, poor weight gain, excessive perspiration, irritability, weak cry, and noisy, labored respirations with intercostal and subcostal retractions, as well as flaring of the alae nasi. The signs of cardiac-induced pulmonary congestion may be indistinguishable from those of bronchiolitis; wheezing is often a more prominent finding in young infants with heart failure than rales. Pneumonitis with or without atelectasis is common, especially in the right middle and lower lobes, due to bronchial compression by the enlarged heart. Hepatomegaly usually occurs, and cardiomegaly is invariably present. In spite of pronounced tachycardia, a gallop rhythm can frequently be recognized. The other auscultatory signs are those produced by the underlying cardiac lesion. Clinical assessment of jugular venous pressure in infants may be difficult because of the shortness of the neck and the difficulty of observing a relaxed state; palpation of an enlarged liver is a more reliable sign. Edema may be generalized and usually involves the eyelids as well as the sacrum and less often the legs and feet. The differential diagnosis is age dependent (Table 436-1).

Table 436-1 ETIOLOGY OF HEART FAILURE

FETAL

PREMATURE NEONATE

FULL-TERM NEONATE

INFANT-TODDLER

CHILD-ADOLESCENT