15.2 Heart disease

Congenital malformations affecting the heart and/or great vessels occur in a little under 1% of newborn infants. Eight defects are relatively frequent and together make up approximately 80% of all congenital heart disease (Table 15.2.1). The remaining 20% of defects comprise a large number of abnormalities, some being quite rare and/or complex malformations.

Table 15.2.1 Relative frequency of common congenital heart defects

| Defect | Approximate frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) | 30 |

| Persistent arterial duct (ductus arteriosus; PDA) | 12 |

| Atrial septal defect (ASD) | 8 |

| Pulmonary stenosis | 8 |

| Aortic stenosis | 5 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 5 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 5 |

| Transposition of the great arteries | 5 |

Acyanotic defects

Common defects with a left-to-right shunt are:

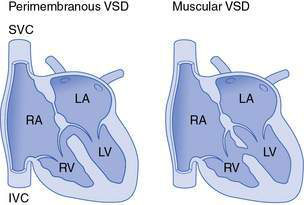

Ventricular septal defect

These comprise around 30% of all cardiac defects. They vary from tiny defects, of pinhole size, to huge defects. Small defects are more common than large ones and are usually asymptomatic. Defects are frequently situated in the region of the membranous septum (perimembranous defects), but VSDs involving the muscular septum are also common (Fig. 15.2.1). Very tiny muscular defects may be demonstrated by echocardiography in infants with no clinical signs to suggest a septal defect.

Investigation

With small defects, the chest X-ray and electrocardiogram (ECG) are frequently normal. With larger defects, the chest X-ray shows cardiomegaly and increased pulmonary plethora (see Fig. 15.1.6). The ECG often shows biventricular hypertrophy. The site and size of the defect can be documented well with echocardiography. Cardiac catheters to document degree of shunting are rarely done but may be performed to measure pulmonary vascular resistance and response to pulmonary vasodilators in patients thought to have pulmonary hypertension secondary to a left-to-right shunt.

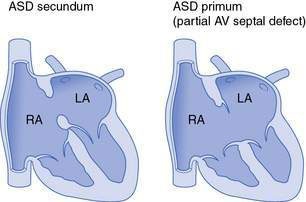

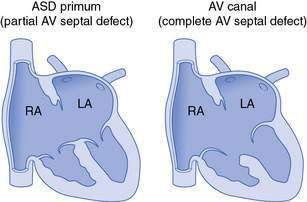

Atrial septal defect

Defects of the atrial septum are usually in the central part of the septum and are termed ‘secundum’ ASD (Fig. 15.2.2). Unlike small VSDs and PDAs (which tend to be associated with loud murmurs), small ASDs may go completely undetected because the volume of blood flow across the defect is small and also the pressure gradient across the defect, and hence the velocity of blood flow, are both low. With larger defects, a significant shunt is present, and this is rarely associated with pulmonary hypertension. Even large ASDs seldom cause symptoms in early childhood. If patients with large defects reach adult life without surgery, they may develop atrial arrhythmias in middle adult life and often have reduced exercise capacity, even if arrhythmias are not a problem. Isolated ASDs hardly ever lead to Eisenmenger syndrome.

The characteristic findings in children with an ASD are related to the increased blood flow through the right side of the heart and right heart enlargement. A parasternal heave related to a dilated right ventricle may be palpable. An ejection systolic murmur, due to increased pulmonary blood flow, is present in the pulmonary area but not usually louder than grade 2/6 and not harsh in character. A soft mid-diastolic murmur may be heard at the lower sternal border, secondary to increased flow across the tricuspid valve. The aortic and pulmonary components of the second heart sound are fixed and widely split (i.e. loss of the normal variation in separation during inspiration and expiration; see Fig. 15.1.2).

Obstructive heart defects

The following defects have no shunt when they occur in isolation, and are obstructive lesions:

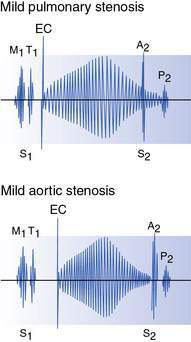

Pulmonary stenosis

Most patients are asymptomatic in infancy and childhood because very severe (‘critical’) obstruction is uncommon and even moderate obstruction is generally well tolerated. An ejection systolic murmur is heard at the left upper sternal edge and radiates through to the back. An early ejection sound (ejection click) is usually audible at the left sternal border (Fig. 15.2.4) with valvar stenosis.

Aortic stenosis

Except in very severe cases, affected children are symptom-free in infancy and early childhood, and present with the chance finding of an ejection systolic murmur over the precordium and in the aortic area. Characteristically, with valvar stenosis the murmur is best heard to the right of the sternum and radiates to the carotids. A thrill is commonly present over the carotids and may also be felt in the aortic area. An ejection click is usually heard with valvar stenosis (see Fig. 15.2.4) and is often most easily audible at the apex or lower left sternal border. In more severe cases a forceful apical impulse due to left ventricular hypertrophy may be apparent. In subaortic stenosis the murmur is best heard at the left sternal edge and a click is not heard. Conversely, the murmur of supravalvar stenosis is often best heard over the carotid artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree