Hearing Loss and Deafness

Laurel M. Wills

Karen E. Wills

I. Description of the condition. A broad understanding of childhood deafness or hearing loss goes beyond traditional medical or audiological definitions to include developmental, linguistic, and sociocultural implications as well. Advances in communication therapies, progressive special education policy, and “high-tech” devices, such as cochlear implants or frequency modulation (FM) listening systems, have dramatically changed the developmental outlook for children with hearing loss. Individualized care management decisions must account for the following characteristics:

A. Degree or severity of hearing loss.

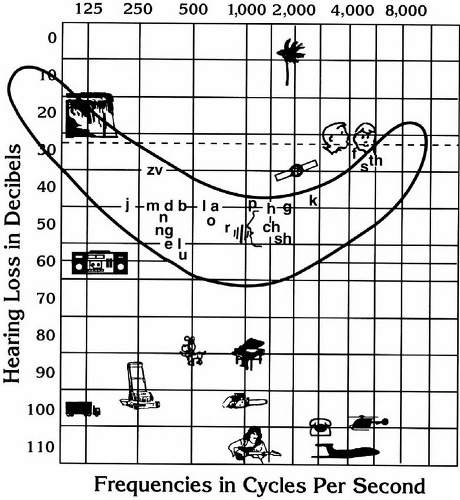

“Normal” hearing is defined as the ability to detect a full range of environmental and speech sounds at a whispering volume of 10 to 20 decibels (dB), whereas conversational speech typically registers at 50 to 60 dB.

Mild (25 to 40 dB range), moderate (41 to 55 dB), moderately severe (56 to 70 dB), severe (71 to 90 dB), and profound (90 dB or higher) degrees of deafness are associated with diminishing capability to detect and discriminate speech and environmental sounds.

The configuration or profile of hearing loss, depicted as an audiogram (Fig. 50-1), varies for each child, with better hearing in certain frequencies than in others, and with separate profiles displayed for the right and left ears.

The audiogram may or may not accurately reflect the functional listening level. For example, one child with moderate hearing loss might be able to comprehend what she hears better than a second child with only mild hearing loss. Deafness is not simply “turning down the volume” on normal hearing; it may also involve distortion of speech sounds that are heard. “Listening skills” are influenced by multiple factors including the child’s biomedical status, cognitive and social-communicative skills, and past experiences (schooling, speech-language therapy, hearing aid use, family support, etc., as described further below).

B. Type and anatomic location of lesion causing hearing loss.

Conductive hearing loss commonly results from conditions that interfere with the functioning of the eardrum or ossicles, but leave the hearing nerve intact, such as middle ear infections, effusions, or cholesteatoma. Conductive hearing loss is generally in the mild to moderate range.

Sensorineural hearing loss is defined as a dysfunction of the cochlear hair cells in the inner ear or of auditory nerve itself (8th cranial nerve), preventing transmission of sound signals to the brain.

Auditory neuropathy refers to dysfunction at one or more points along the auditory pathway of the nervous system (8th nerve, auditory brainstem nuclei, central auditory cortex), with or without an otherwise normally functioning cochlea.

Mixed hearing losses involve both peripheral (outer and middle ear) and central (inner ear and neural) components of the auditory pathway.

Children with mild or unilateral hearing loss may have age-typical speech skills, and thus may go undiagnosed until well into their elementary school years. They may present with symptoms of inattention, distractibility, language or learning deficits, or irritable mood; thus, a basic hearing screen should be a standard part of developmental-behavioral pediatric assessments.

Children with fluctuating hearing loss (associated with chronic severe otitis media, or severe bilateral cerumen impaction) in early childhood may show distorted or delayed speech and language development, which sometimes can persist into later childhood.

C. Age of onset of hearing loss.

Children who are born deaf or who lose their hearing prior to acquiring spoken language (“prelingual deafness”), relative to those who lose their hearing later on (“postlingual deafness”), are usually at a communicative disadvantage with regard to developing and/or preserving spoken language skills.

Figure 50-1. Audiogram showing a comparison of the frequency and intensity of various environmental and speech sounds.

Older children or adolescents who are late-deafened (e.g., from meningitis or progressive hearing loss), but still fluent in their native spoken language, are usually optimal candidates for restoration (rehabilitation) of oral-aural communication skills.

Hearing loss that is progressive may be detected and treated later than stable hearing losses. Often, older children or adolescents attempt to minimize or deny the increasing severity of a progressive hearing loss, just as older adults often do, to avoid the psychosocial stigma of wearing hearing aids or acknowledging a “disability.”

D. Age at (and interval between) identification and intervention.

Prelingual or congenital deafness confers risk for loss of stimulation to the auditory pathways during sensitive early developmental periods, hence the recommendation to intervene early with hearing aids or cochlear implants, when appropriate. Similarly, in cases of acquired or postlingual deafness, early detection and expeditious intervention improves prognosis.

Informal office methods of “testing” hearing in babies and young children (such as clapping or ringing a bell, and then watching for response) are considered unreliable, and can result in delayed diagnosis. When parents report concern about a child’s hearing due to symptoms such as “not responding to sounds at home”, “not listening”, or “not talking” at the expected age, formal referral to a pediatric audiologist is indicated.

Universal newborn hearing screening, now considered a standard of care, has dramatically improved the rate of early detection of childhood hearing loss, allowing for earlier intervention with strategies that improve access to oral-aural (spoken) and/or manual-visual (signed) language.

Only ∽10% of deaf babies are born to deaf parents, whereas ∽90% of deaf babies are born to hearing parents. These “deaf-of-deaf” children are more likely to grow up as “native” signers, due to the rare natural circumstance of having exposure, since birth, to one or more fluent Sign Language models. In contrast to the reaction of most hearing parents, those who identify as culturally deaf may be pleased when their child is also born deaf; some may express concerns about raising a child with “normal” hearing.

E. Coexisting disabilities related to cause of hearing loss.

Approximately one-third of children with hearing loss have additional medical or neurological diagnoses, as described below. The other two-thirds of children tend to be healthy, “typically developing” youngsters with “isolated” hearing loss, usually genetic in origin.

Dual sensory loss (hearing and vision) occurs in a number of conditions, such as prenatal cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection or Usher Syndrome. In general, it is critically important to protect and optimize vision for purposes of speech (lip)-reading and/or signing. Thus, formal periodic evaluation with a pediatric ophthalmologist is strongly recommended for all hard of hearing and deaf children.

Children born in developing countries (e.g., international adoptees and immigrant children) and low-income children with less access to healthcare are more likely to have late-identified hearing loss or multiple disabilities.

F. Psychosocial experience and home environment.

Positive adjustment and social-emotional well-being among deaf children is closely linked to the quality of parent-child communication, (irrespective of modality), as well as to warm, responsive nurturing, and developmentally appropriate expectations within the parent-child relationship (see parenting resources in bibliography). Chronic frustration, conflict, and chaos in the home are linked to behavior and emotional problems in deaf children. Since 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who are likely to know little about deafness, the diagnosis of deafness can be a crisis that tries the family’s coping resources, demanding support systems within their extended family and community, as well as support from healthcare and education professionals.

II. Epidemiology.

Twenty million Americans of all ages have a hearing loss.

Roughly 1 million children and adolescents have a “communicatively significant” hearing loss.

1 to 2/1,000 live births will have severe or profound deafness.

6 to 10/1,000 will have milder degrees of hearing loss.

Males and females are equally affected.

Preventative measures, such as vaccines against rubella, Hemophilus influenza B, and pneumoccal disease, as well as appropriate treatment of otitis media and neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, have all markedly reduced the incidence of childhood hearing loss in developed countries.

Academic underachievement, functional illiteracy, and underemployment remain significant concerns for this population.

III. Etiology.

A. Genetic causes account for roughly 50% to 60% of all children with hearing loss, and of these genetic causes, about one-third are “deafness-related syndromes” and two-thirds are “nonsyndromic”. Laboratory testing and DNA molecular analysis is now available for some of the more common gene mutations, such as Connexin 26 (GJB2). Malformations of the cochlea or other inner ear structures can result in hearing loss and, in some children, problems with balance or equilibrium. Other examples include Usher syndrome (sensorineural deafness associated with progressive vision loss from retinitis pigmentosa), Treacher-Collins syndrome (conductive or mixed hearing loss, associated with dysmorphic facies and eye findings), and Waardenburg syndrome (sensorineural deafness and pigmentary changes of the hair and irises). All of these are examples of syndromes usually associated with normal intelligence.

B. Nongenetic or “acquired” hearing loss can be separated into etiologies occurring in the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree