7 | Gynecologic Infections |

Infections of the Vulva (Vulvitis) Introduction and Pathogenesis

The vulva and, in particular, the vaginal orifice (introitus) are among the most sensitive regions of the body because of their rich supply with sensory nerves. Any disorder and inflammation in this region is therefore experienced as extremely uncomfortable and is often noticed before anything becomes visible.

On the one hand, the external region is quite resistant to most pathogens because of the keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium. On the other, the vaginal orifice with its very delicate epithelium may respond with pain to the mere touch even in the absence of any inflammation. In addition, infections and their treatments may lead to an increase in the sensitivity and tenderness of this region.

Another problem is the close proximity to the anus and, therefore, to large amounts of facultative pathogens (the intestinal flora). These bacteria and their metabolites often generate an unpleasant odor, which may lead to excessive washing behavior. Even without using soap, repeated washing may result in a rough and dry skin—thus causing considerable other problems in the long term, for example, skin lesions, more frequent infections, and allergies. This can be remedied by proper skin care, such as using ointments containing lavender oil.

When discussing the vulva and its susceptibility to infections, the anal region and the properties of the skin in this region should not be ignored. Hence, the prevention of infections in the genital region begins externally, namely, with the vulva and the anal region.

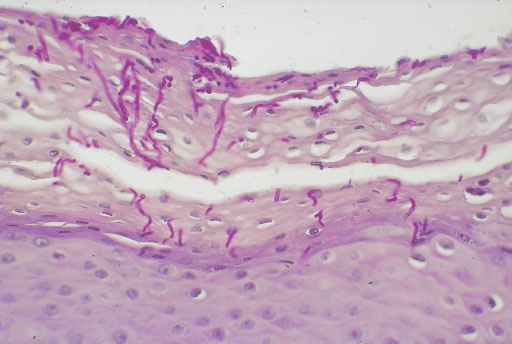

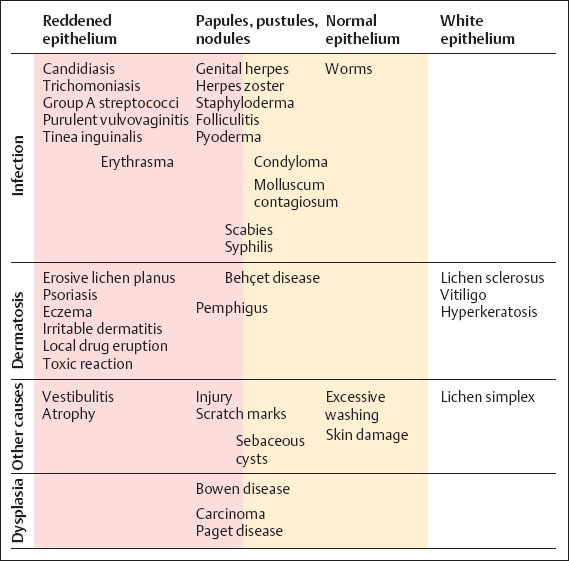

In addition to skin lesions and infections, a number of dermatoses occur in the vulvar region. These, in turn, may promote infections, or they may be confused with infections—or they are actually the cause of complaints (Table 7.1).

In some patients, a presumed infection is treated far too long—only because bacteria (e. g., intestinal bacteria) or a harmless yeast species have been detected. For this reason, we discuss here dermatoses and other disturbances together with vulvar infections with which they may be confused.

Infections occur preferentially, when:

skin lesions—due to intercourse, rhagades (Fig. 7.1), excessive skin care, and scratching—promote the invasion of pathogens, e. g., herpesviruses, papillomaviruses, Treponema, group A streptococci

skin lesions—due to intercourse, rhagades (Fig. 7.1), excessive skin care, and scratching—promote the invasion of pathogens, e. g., herpesviruses, papillomaviruses, Treponema, group A streptococci

pathogens infect skin appendages (glands, hair follicles), e. g., Staphylococcus aureus (folliculitis)

pathogens infect skin appendages (glands, hair follicles), e. g., Staphylococcus aureus (folliculitis)

congestion or the formation of pouches (obstruction of sebaceous glands or Bartholin gland, or synechia of the preputium) create favorable conditions for bacteria to multiply, e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, intestinal pathogens, gonococci

congestion or the formation of pouches (obstruction of sebaceous glands or Bartholin gland, or synechia of the preputium) create favorable conditions for bacteria to multiply, e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, intestinal pathogens, gonococci

pathogens are able to penetrate the epithelium by means of enzymes, e. g., Candida albicans, group A streptococci

pathogens are able to penetrate the epithelium by means of enzymes, e. g., Candida albicans, group A streptococci

pathogens, or their vectors, actively bore through the skin by means of bites or stings, e.g., ticks, mosquitoes, pubic lice, mites, Schistosoma, creeping eruption (larva migrans).

pathogens, or their vectors, actively bore through the skin by means of bites or stings, e.g., ticks, mosquitoes, pubic lice, mites, Schistosoma, creeping eruption (larva migrans).

Frequent and long bathing sessions let the skin swell and make it easier for pathogens from the perianal region to attach and penetrate.

Onset and persistence of many infections are also promoted through conditions that weaken or damage the skin, such as allergic noxa, eczema, diabetes mellitus, or mechanical means (scrubbing, rubbing, or scratching), and also by moisture in large skin folds (e. g., erythrasma).

The common misconception that proper hygiene would involve frequent and excessive washings—using all kinds of washing lotions that are marketed as being especially effective—is often the cause of itching chronic vulvitis. Typical pathogens are rarely found in this situation.

Once infections reach the deeper skin layers, they are painful because the vulva is richly supplied with sensory nerves. Redness and swelling are characteristic signs of such infections (Fig. 7.2).

If no pathogens can be detected, diagnosis may be difficult. Allergy, eczema, or other dermatological problems should then be considered.

The symptom of pain may be absent in the case of superficial intradermal infections (condylomas, erythrasma, pityriasis [tinea] versicolor). Simultaneous infections with several pathogens are possible.

Fig. 7.1 Vulva of a 25-year-old patient complaining about itching. The perineal region shows dry skin with rhagades.

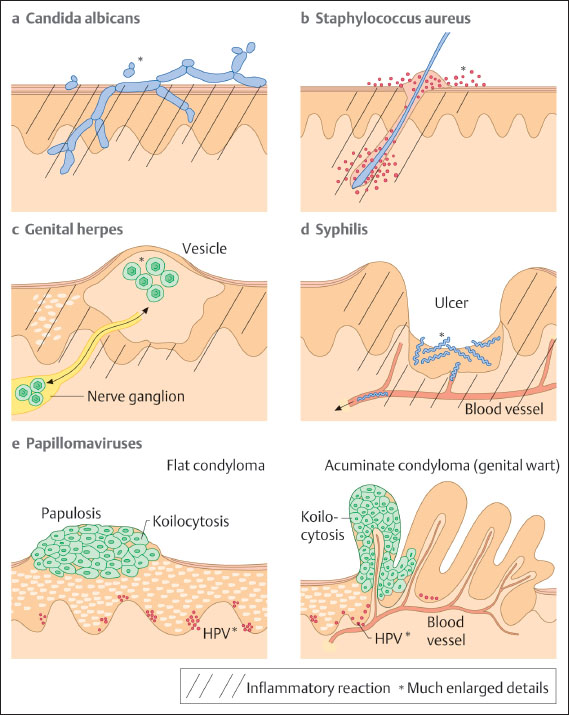

Fig. 7.2 Schematic illustration of pathogen localization and pathogen spread in various diseases of the vulva. The individual pathogens are shown much enlarged. Areas of inflammatory reaction are indicated by hatching.

Table 7.2 Options forlocal treatment of diseases of the vulva

| Type of drug | Preparation |

|---|---|---|

Anti-infective agents | Antibiotics | Metronidazole, clindamycin |

Antimycotics | Nystatin, clotrimazole, etc. | |

Antiseptics | Polyvidone iodine, hexetidine, dequalinium chloride, nifuratel | |

Virostatics | Acyclovir, foscarnet | |

Hormone | Estrogens | Estrogen ointment/ovules |

Cortisol | Topical: e. g., clobetasol, triamcinolone | |

Removal | Ablation | Surgery, laser, electric loop |

Denaturation | Trichloroacetic acid (> 50%), podophyllotoxin, albothyl | |

Immunological | Immunomodulators | Imiquimod, tacrolimus |

Skin care | Lubricant | Ointments containing lavender oil |

Skin Care in the Anogenital Region

The principle source of bacteria in the genital region is the anus, since up to 50 % of the discharged excrement (feces) consists of bacteria. Anyone concerned with the genital region tries to keep this area as clean as possible because of the offensive odor of bacterial metabolites. If the skin is sensitive, this easily causes skin lesions and these, in turn, promote the growth of bacteria.

The best skin care of the anal region consists of lubricating the anus with ointments containing lavender oil prior to having a bowel movement. This not only facilitates defecation and prevents anal lesions, but it also reduces the amount of bacteria colonizing the skin.

Lubricating the vulva and the vaginal orifice with ointments containing lavender oil prior to intercourse prevents injury to the skin if there is a disposition for it, and it diminishes the development of infections. (Caution: condoms made of latex are damaged by oil.)

Vulvitis Caused by Fungi

Fungi are the most common cause of inflammation in the external genital region. Hence, they should always be considered in case of any complaints, and they should be excluded as a contributing factor.

Candidiasis

Frequency, pathogen, transmission, and risk factors. Vulvitis caused by fungi is the most common infection associated with an inflammatory reaction of the vulva. In most patients, it is caused by Candida albicans (> 90%) and only very rarely by C. tropicalis, C. crusei, or other species. Up to 5– 10% of gynecological patients may be affected. Some women rarely have a manifest infection, while others have frequent infections.

The pathogen Candida albicans is widely distributed. It is taken up together with food and through human contact. It is thus found in up to 50% of adults as a colonizing pathogen in the mouth and intestine.

Some of the factors promoting the onset of Candida infections are known, e. g., diabetes mellitus, antibiotic therapy, high doses of estrogen, and immunosuppression. However, the majority of women suffering from recurrent Candida infections do not have any of the known risk factors.

Skin lesions (Fig. 7.1) promote the onset of a fungal infection. On the other hand, fungi are also found as colonizing organisms in various forms of dermatitis and are then not the sole cause of the complaints.

Symptoms. The main symptom is itching; if there is only burning, this rules out fungal infection as a cause. Only very pronounced candidiasis is associated with pain. Some patients just complain of discharge, which means that only the vagina is affected.

Clinical picture. Redness and swelling of the vulva associated with flaky, crumbly discharge (Fig. 7.3) are such characteristic symptoms that this picture can hardly be confused with any other forms of vulvitis. More difficult is the diagnosis when there is redness with tiny nodules (Fig. 7.4), or pustules with redness (Fig. 7.5), or even pustules without redness (Fig. 7.6). Candidiasis is easier to identify if the vulva shows dry redness (Fig. 7.7), or when there are discrete white stipples (Fig. 7.8) or discrete tiny rings (remains of pustules) in the region of the vaginal orifice. Fungus-induced pustules persist for many days, in contrast to those induced by herpesviruses. If the vulvar redness is spread over larger areas with irregular boundaries (Fig. 7.9), this indicates very severe candidiasis—often in association with a basic disease, such as diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 7.3 Vulvitis with flaky discharge, caused by Candida albicans in a 43-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.4 Vulvitis with nodules, caused by Candida albicans in a 40-year-old patient.

Diagnosis:

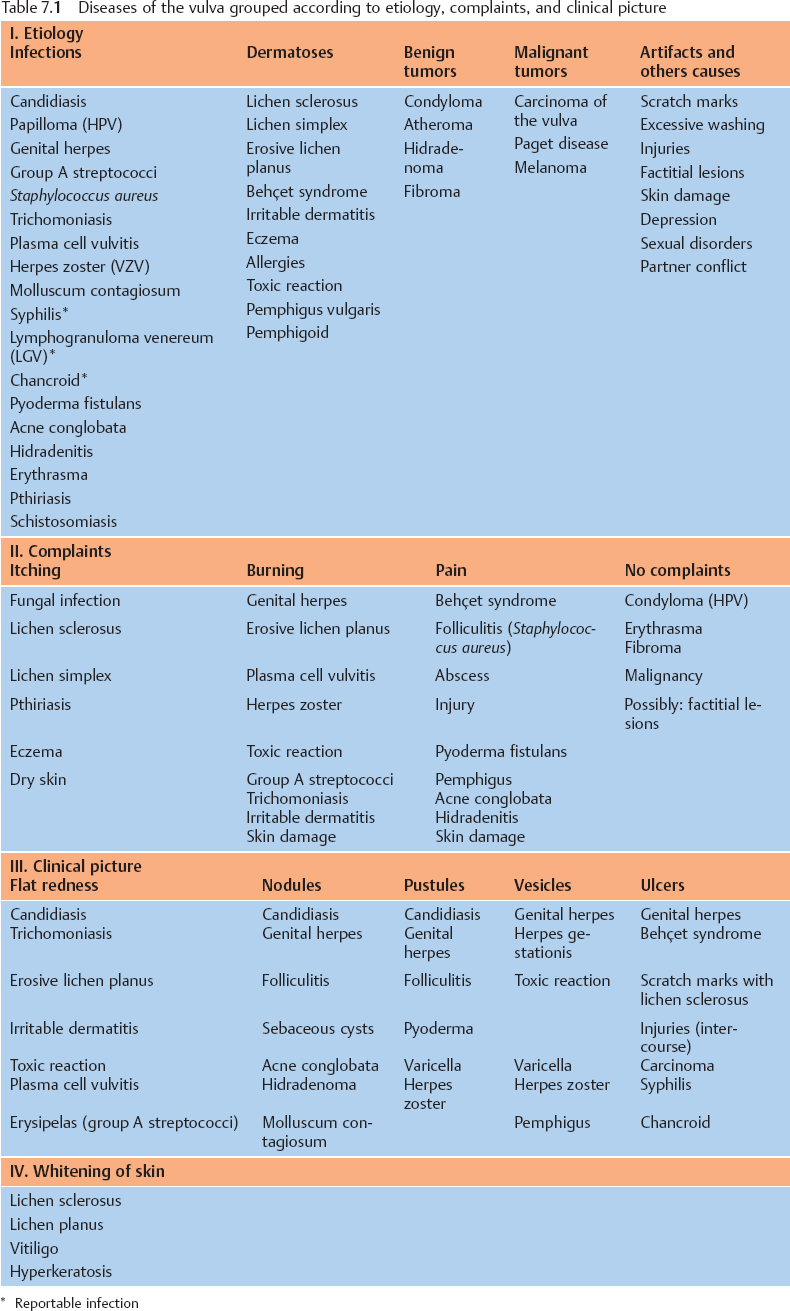

Microscopy. Diagnosis is most successful when based on microscopic examination of the discharge. Using the wooden handle of a cotton swab, some discharge (including flakes or crumbs, if possible) or the scrapings from pustules or nodules are mixed into a drop of 0.1% methylene blue solution and then screened for fungal elements.

Microscopy. Diagnosis is most successful when based on microscopic examination of the discharge. Using the wooden handle of a cotton swab, some discharge (including flakes or crumbs, if possible) or the scrapings from pustules or nodules are mixed into a drop of 0.1% methylene blue solution and then screened for fungal elements.

Because the distribution of yeast cells is usually inhomogeneous, it is better to look for flakes that are then homogenized in the methylene blue solution. These flakes consist of exfoliated epithelial cells that are clumped together by elongated, adhesive yeast elements (pseudomycelia).

Some examiners recommend that 10% potassium hydroxide solution is used for dissolving the epithelial cells, but this is hardly necessary in the genital region. Staining is not required because viewing the sample under a phase-contrast microscope makes it easy to find yeast cells.

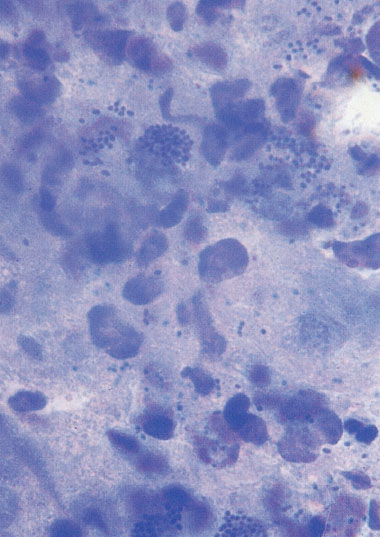

If typical pseudomycelia (treelike aggregations of elongated yeast cells, often attached to each other only by pointed connections; Fig. 7.10 and Fig. 3.1, p. 27) are detected, the diagnosis is confirmed, and further diagnostic steps are superfluous. Microscopic evidence of pseudomycelia is virtually synonymous with the diagnosis of candidiasis. Occasionally, it may be easier to detect these characteristic fungal elements in swabs from the vagina.

The most sensitive method of detection is fluorescence microscopy. After adding a fluorescent dye that specifically stains the walls of yeast cells, the individual budding cells can be recognized between the epithelial cells.

In the absence of leukocytes, the presence of numerous small budding cells lets one suspect colonization with Candida glabrata, while fairly large, elongated budding cells indicate colonization with Saccharomyces.

Fig. 7.5 Vulvitis with pustules and pronounced redness, caused by Candida albicans in a 46-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.6 Vulvitis with pustules but very little redness, caused by Candida albicans in a 34-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.7 Dry vulvitis caused by Candida albicans in a 43-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.8 Vulvitis with tiny white nodules in the region near the vaginal orifice, caused by Candida albicans.

Fig. 7.9 Severe chronic vulvitis caused by Candida albicans in a 54-year-old patient with diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 7.10 Micrograph illustrating pronounced candidiasis with pseudomycelia and numerous leukocytes. Discharge stained with 0.1 % methylene blue.

Culture. The material on the cotton swab used for preparing the wet mount may be smeared onto Sabouraud agar or washed out in a tube containing Sabouraud solution (see Table 3.1, p. 25).

Culture. The material on the cotton swab used for preparing the wet mount may be smeared onto Sabouraud agar or washed out in a tube containing Sabouraud solution (see Table 3.1, p. 25).

When taking swabs from a dry vulva, the cotton swab should be premoistened in order to make it absorbent. This may be done by briefly inserting it into the vagina, or by dipping it into culture medium or even tap water.

Fungal cultures are required whenever the patient’s complaints and the clinical picture suggest a fungal infection but fungal elements cannot be detected microscopically. In addition, cultures for the purpose of a differential diagnosis are indicated whenever only budding cells (but no pseudomycelia) are seen under the microscope and apathogenic yeasts have to be excluded (e. g., Sac-charomyces cerevisiae, baker or brewer yeast).

Determination of resistance is not required for routine diagnosis.

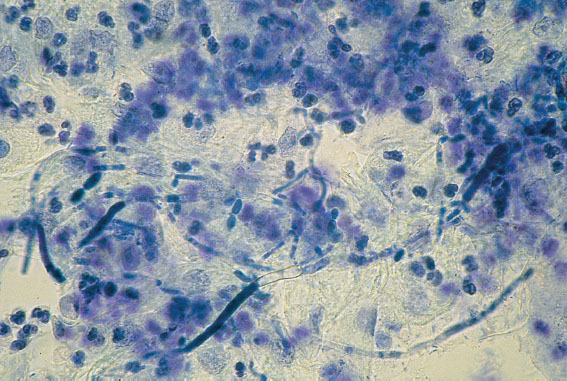

Biopsy. In inconclusive cases (e. g., hyperkeratosis, adhesive coating, questionable nodules), a biopsy may be helpful (for the method, see p. 61). Fig. 7.11 shows the clinical picture of candidiasis, while Fig. 7.12 shows the corresponding histology. The histological preparation (staining with periodic acid–Schiff reagent, PAS) shows in an impressive way that fungi are able to penetrate the epithelium and do not always stay on the surface, where they are easier to eliminate.

Biopsy. In inconclusive cases (e. g., hyperkeratosis, adhesive coating, questionable nodules), a biopsy may be helpful (for the method, see p. 61). Fig. 7.11 shows the clinical picture of candidiasis, while Fig. 7.12 shows the corresponding histology. The histological preparation (staining with periodic acid–Schiff reagent, PAS) shows in an impressive way that fungi are able to penetrate the epithelium and do not always stay on the surface, where they are easier to eliminate.

Serology. It hardly plays a role in genital candidiasis (only in cases of systemic infections, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals).

Serology. It hardly plays a role in genital candidiasis (only in cases of systemic infections, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals).

Differential diagnosis (Fig. 7.13). Apart from other infections, many dermatoses should be considered. A fungal infection often exists in addition to a dermatosis. The fungal infection then represents an extra burden for the damaged skin to endure:

folliculitis (Staphylococcus aureus)

folliculitis (Staphylococcus aureus)

genital herpes, where burning is the predominating symptom and the various herpes stages (vesicles, pustules, erosions) are of very short duration, lasting only a few hours or days)

genital herpes, where burning is the predominating symptom and the various herpes stages (vesicles, pustules, erosions) are of very short duration, lasting only a few hours or days)

tinea inguinalis (caused by dermatophytes)

tinea inguinalis (caused by dermatophytes)

infection with group A streptococci

infection with group A streptococci

infection with papillomavirus (does not cause any symptoms)

infection with papillomavirus (does not cause any symptoms)

eczema (contact dermatitis/allergy)

eczema (contact dermatitis/allergy)

psoriasis vulgaris

psoriasis vulgaris

erosive lichen planus

erosive lichen planus

lichen simplex chronicus (circumscribed neurodermatitis)

lichen simplex chronicus (circumscribed neurodermatitis)

pinworms in the perianal region (causing itching)

pinworms in the perianal region (causing itching)

bowenoid papulosis (easy to identify by using the acetic acid test).

bowenoid papulosis (easy to identify by using the acetic acid test).

Fig. 7.11 Apparent hyperkeratosis in a 32-year-old patient, identified in the histological preparation as candidiasis.

Fig. 7.12 Histological preparation taken from the skin area shown in Fig. 7.11. Fungal hyphens invading the epithelium are easily detected in the PAS-stained cross-section.

Therapy. Treatment depends on the severity of the disease and on the patient’s history and condition. Normally, yeasts are not life threatening for immunocompetent individuals; they are rather a nuisance. Therapy is therefore only necessary when there are complaints of inflammatory reactions, during pregnancy, and when the immune system is suppressed. In about 15% of women without complaints, Candida albicans can be detected at low counts in cultures from vaginal swabs.

As illustrated in Fig. 7.12, yeasts are able to penetrate into the epithelium even in immunocompetent persons; they are therefore not easily removed by washing. When the immune system is intact, an antimycotic drug will bring quick relieve.

Therapy for Rarely/Occasionally Occurring Fungal Infections

Therapy is normally not a problem here. Short-term topical treatment is the rule, and it should always be a combination of cream for external use and vaginal ovules/tablets for internal use. In the past, treatment for several days (five days) has been the norm, but short-term therapy (one to three days) is gaining acceptance. By simply increasing the concentration of the active component, the same therapeutic results can be achieved—and the patients appreciate the shorter term of treatment.

A single oral dose is also an option. It has the advantage that the drug can reach also those areas left out by topical application. This form of treatment can also be applied during the period.

Antimycotic drugs. See p. 48.

Fig. 7.13 Differential diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis.

Therapy for Chronic Recurrent Candidiasis

Frequently occurring fungal infections—more than four per year, up to every three to four weeks—due to treatment failure or reinfection (relapses) call for a different approach. The causes and cofactors must be identified because it is quite possible that the fungal infection is only a superinfection. One should also consider that not every itch is caused by fungi and that the fungus detected in the culture may be a harmless colonizing organism.

Approach to Recurrent Candidal Vulvitis

Typing of Candida species: the most severe symptoms are induced by C. albicans.

Typing of Candida species: the most severe symptoms are induced by C. albicans.

Exclusion of cofactors: diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression through medication or HIV infection (these are rather rare cofactors).

Exclusion of cofactors: diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression through medication or HIV infection (these are rather rare cofactors).

Condition of the vulvar epithelium, especially in the perianal region: skin lesions, dryness, rhagades, coarse epithelium, anal fissures, and hemorrhoids (these are common cofactors).

Condition of the vulvar epithelium, especially in the perianal region: skin lesions, dryness, rhagades, coarse epithelium, anal fissures, and hemorrhoids (these are common cofactors).

Examination of anal and oral swabs for gathering information on the extent of the patient’s colonization with fungi and also to recognize potential sources of infection.

Examination of anal and oral swabs for gathering information on the extent of the patient’s colonization with fungi and also to recognize potential sources of infection.

Examination and parallel treatment of the patient’s partner: swabs from the penis, mouth, or extremities (a common cofactor).

Examination and parallel treatment of the patient’s partner: swabs from the penis, mouth, or extremities (a common cofactor).

Consultation about washing habits and sexual habits, including inquiring about symptoms observed in the partner (a common cofactor).

Consultation about washing habits and sexual habits, including inquiring about symptoms observed in the partner (a common cofactor).

Inquiring about eating habits: sweets and a diet rich in carbohydrates promote fungal growth in the intestinal tract, which may indirectly increase the transmission of fungi from the anus to the vulva (a less important cofactor).

Inquiring about eating habits: sweets and a diet rich in carbohydrates promote fungal growth in the intestinal tract, which may indirectly increase the transmission of fungi from the anus to the vulva (a less important cofactor).

Termination of the use of ovulation inhibitors is not recommended, as there is no evidence that candidiasis is promoted by relatively low doses of estrogen. High doses of estrogen create a vaginal milieu that is rich in nutrients and sugars, thus promoting the growth of fungi (there is hardly any candidiasis in the genital region in the absence of estrogen).

Termination of the use of ovulation inhibitors is not recommended, as there is no evidence that candidiasis is promoted by relatively low doses of estrogen. High doses of estrogen create a vaginal milieu that is rich in nutrients and sugars, thus promoting the growth of fungi (there is hardly any candidiasis in the genital region in the absence of estrogen).

Therapeutic Options for Frequently Recurring Candida albicans Infections

Treatment with a systemic antimycotic, e. g., fluconazole. The following therapeutic approach has proved useful: prescription of fluconazole (100 mg tablets, four treatments of two tablets each); the first dose immediately, the second dose after one week, followed by culture after two weeks to rule out the presence of Candida in the vagina, the third dose after four weeks, and the fourth dose after eight weeks. The partner should be treated as well (oral dose once or twice).

Treatment with a systemic antimycotic, e. g., fluconazole. The following therapeutic approach has proved useful: prescription of fluconazole (100 mg tablets, four treatments of two tablets each); the first dose immediately, the second dose after one week, followed by culture after two weeks to rule out the presence of Candida in the vagina, the third dose after four weeks, and the fourth dose after eight weeks. The partner should be treated as well (oral dose once or twice).

Avoiding soaps or other skin care products that may irritate the skin, even though they may be marketed as being particularly gentle (the fungus detected in the culture may represent a secondary colonization).

Avoiding soaps or other skin care products that may irritate the skin, even though they may be marketed as being particularly gentle (the fungus detected in the culture may represent a secondary colonization).

Reducing the use of water while intensifying perianal skin care with ointments containing lavender oil (lubrication and protection of the anus prior to defecation).

Reducing the use of water while intensifying perianal skin care with ointments containing lavender oil (lubrication and protection of the anus prior to defecation).

Regular care of the vulva with ointments containing lavender oil after every washing.

Regular care of the vulva with ointments containing lavender oil after every washing.

Inclusion of the partner in the topical or oral treatment (e.g., fluconazole or itraconazole). Regular skin care should include the partner as well (e. g., lubrication of the penis and anal region with ointments containing lavender oil).

Inclusion of the partner in the topical or oral treatment (e.g., fluconazole or itraconazole). Regular skin care should include the partner as well (e. g., lubrication of the penis and anal region with ointments containing lavender oil).

Skin care of the genitals prior to intercourse (lubrication as prevention of microlesions).

Skin care of the genitals prior to intercourse (lubrication as prevention of microlesions).

Attempt to eradicate the fungus by simultaneous nystatin therapy: oral treatment (lozenges), intestinal treatment (coated tablets, four times two tablets per day), and topical treatment (vulva and vagina) for 20 days. Intestinal sanitation requires at least 3 g nystatin per day (taken as powder, if possible); however, the success is limited due to frequent reuptake of exogenous fungus.

Attempt to eradicate the fungus by simultaneous nystatin therapy: oral treatment (lozenges), intestinal treatment (coated tablets, four times two tablets per day), and topical treatment (vulva and vagina) for 20 days. Intestinal sanitation requires at least 3 g nystatin per day (taken as powder, if possible); however, the success is limited due to frequent reuptake of exogenous fungus.

Approach in Case of Treatment Failure

If the findings get worse during therapy, one should also consider a possible intolerance or allergy to the base of the antimycotic ointment (see also irritable vulvitis, p. 109).

If the findings get worse during therapy, one should also consider a possible intolerance or allergy to the base of the antimycotic ointment (see also irritable vulvitis, p. 109).

Many creams and skin care products contain emulsifiers and preservatives that may cause allergies when used for a long time.

Many creams and skin care products contain emulsifiers and preservatives that may cause allergies when used for a long time.

Changing the drug or switching to oral therapy. Short-term treatment with cortisone cream, followed by regular lubrication with ointments containing lavender oil that are free of emulsifiers and preservatives.

Changing the drug or switching to oral therapy. Short-term treatment with cortisone cream, followed by regular lubrication with ointments containing lavender oil that are free of emulsifiers and preservatives.

If one is not dealing with chronic candidiasis: C. albicans may represent only a secondary colonization of skin lesions caused by too much washing or rubbing (lichen simplex).

If one is not dealing with chronic candidiasis: C. albicans may represent only a secondary colonization of skin lesions caused by too much washing or rubbing (lichen simplex).

If one is dealing with a dermatosis: psoriasis (Fig. 7.93, p. 111), for example, may look different in the genital region than at the usual predilection sites.

If one is dealing with a dermatosis: psoriasis (Fig. 7.93, p. 111), for example, may look different in the genital region than at the usual predilection sites.

Biopsy in case of inconclusive findings in order to exclude dermatosis.

Biopsy in case of inconclusive findings in order to exclude dermatosis.

Infections Caused by Other Fungi

Other yeast species (see Table 1.2, p. 8) play a minor role.

Candida glabrata (Formerly: Torulopsis glabrata)

This species can only form budding cells. It is almost always a harmless colonizing organism. C. glabrata, which affects more the vagina than the vulva, is often found together with C. albicans— and it is the species that remains after therapy (selected species), thus still yielding positive cultures.

Typical for a colonization by C. glabrata is the microscopic finding of many small budding cells in the native preparation, without any signs of an inflammatory reaction (very few leukocytes), or the fact that the patient is free of symptoms although the fungal culture is still positive. If symptoms are present but only C. glabrata can be detected in the culture, one should search for other causes of the symptoms.

Common antimycotic drugs are rather ineffective against C. glabrata, and increasing the dose in an attempt to eliminate this yeast species is not a good idea.

In the presence of chronic systemic diseases and immunosuppression, C. glabrata may also be detected in blood cultures.

Dermatophytes (Tinea Inguinalis)

This fungal skin infection is also called tinea cruris, ringworm of the groin, and jock itch. Unlike yeasts, which prefer moist and warm body parts, dermatophytes tend to infect dry skin areas. They rarely occur in the genital region—and if they do, then rather in the perivulvar region.

Pathogen. Usually Trichophyton rubrum.

Clinical picture. Round, flat, and red foci of inflammation with distinct margins. Very itchy and spreading (Fig. 7.14).

Diagnosis:

Clinical picture. Red patches with distinct margins.

Clinical picture. Red patches with distinct margins.

Microscopy. Mycelia form treelike ramifications, exhibiting true bifurcations and septae.

Microscopy. Mycelia form treelike ramifications, exhibiting true bifurcations and septae.

Culture.

Culture.

Fig. 7.14 Tinea inguinalis caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum mostly in the perivulvar region; the infected area is characterized by distinct margins. (Photograph courtesy of Dr. S. A. Qadripur, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital, Göttingen, Germany.)

Differential diagnosis:

candidiasis

candidiasis

erythrasma

erythrasma

eczema

eczema

psoriasis.

psoriasis.

Therapy. Imidazole preparations (see p. 49).

Vulvitis Caused by Bacteria

Because of the close proximity to the anus, an abundance of bacteria can be cultured from swabs of the vulva. However, most of them are intestinal bacteria and are therefore only contaminating or colonizing microbes.

The most important bacterial species able to cause infection and inflammation of the vulvar skin are Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. The clinical pictures may be quite different.

Pyoderma of the Vulva and Surrounding Areas

Pyoderma, a purulent infection of the skin, is caused by pus-forming bacteria. The various forms of pyoderma include:

folliculitis (S. aureus)

folliculitis (S. aureus)

furuncle and carbuncle (S. aureus)

furuncle and carbuncle (S. aureus)

impetigo contagiosa (group A streptococci, occasionally also S. aureus)

impetigo contagiosa (group A streptococci, occasionally also S. aureus)

vulvitis in young girls (group A streptococci)

vulvitis in young girls (group A streptococci)

erysipelas (group A streptococci).

erysipelas (group A streptococci).

Infections Caused by Staphylococcus aureus

Folliculitis

An infection of hair follicles by S. aureus. The clinical picture is easily diagnosed by colposcopy when the inflammatory process (nodules, pustules) is associated with hair follicles (Figs. 7.15–7.17).

Pathogen. S. aureus.

Diagnosis. Clinical picture and detection of S. aureus in the culture.

Therapy. Antibiotics are administered for five days. Without an antibiogram, a cephalosporin of the second generation is appropriate; with antibiogram and in case of sensitivities, amoxicillin or other antibiotics may be administered. At an early stage, one may also attempt to cure the infection by means of topical application of polyvidone iodine cream.

Differential diagnosis:

Vulvitis pustulosa caused by Candida albicans (pustules are not associated with hair follicles; see Figs. 7.4–7.6, p. 71).

Vulvitis pustulosa caused by Candida albicans (pustules are not associated with hair follicles; see Figs. 7.4–7.6, p. 71).

Genital herpes (rapid course of stages with vesicles and erosions during the primary infection, see Figs. 7.31–7.38 (pp. 84–86); or temporary groups of vesicles and pustules at a single site only in case of a relapse, see Fig. 7.42, p. 88).

Genital herpes (rapid course of stages with vesicles and erosions during the primary infection, see Figs. 7.31–7.38 (pp. 84–86); or temporary groups of vesicles and pustules at a single site only in case of a relapse, see Fig. 7.42, p. 88).

Fig. 7.15 Vulvitis pustulosa caused by Staphylococcus aureus in a 24-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.17 Vulvitis pustulosa caused by Staphylococcus aureus; the pustules are clearly associated with hair follicles.

Fig. 7.18 Vulvitis with pustules of the sebaceous glands caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Fig. 7.19 Small abscess of the vulva caused by Staphy-lococcus aureus in a 45-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.20 Abscess in the right labium majus caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Molluscum contagiosum (see Fig. 7. 51, p. 91; easy to identify by colposcopy).

Molluscum contagiosum (see Fig. 7. 51, p. 91; easy to identify by colposcopy).

Furuncle/Carbuncle

This is an infection originating from a hair follicle or sebaceous gland (Figs. 7.18, 7.19) with central necrolysis of deeper tissues caused by S. aureus (Figs. 7.20, 7.21). It is usually a smear infection promoted by insufficient hygiene, but other causes are also possible, such as basic diseases and immunosuppression. Carbuncle is the most severe form and is always very painful because of its rapid increase in size and the severe inflammatory reaction. It may also occur in young girls (Fig. 7.23).

Pathogen. S. aureus.

Therapy. The abscess is opened by stab incision (Fig. 7.21) after anesthesia with ELMA cream (wait at least 30 minutes until the cream becomes effective). This is followed by skin care with polyvidone iodine cream. Treatment with oral antibiotics is rarely necessary.

Infections Caused by Group A Streptococci

Vulvitis

Pathogen. β-hemolytic streptococci of serogroup A (Streptococcus pyogenes).

Transmission and pathogenesis. This infection is promoted by insufficient hygiene and mechanical irritation of the skin, particularly in the absence of estrogens and a lactobacillus flora. It is caused by smear infection with the fingers from the mouth to the genitals (oral–vulva infection) and occurs typically in prepubertal girls (Fig. 7.22). It is increasingly seen also in women, perhaps as a result of oral–genital sexual contact.

Clinical picture. The diffuse redness, which spreads over a large area (Figs. 7.24, 7.25, 7.27), is associated with leukocytic discharge (Fig. 7.28) and often affects also the perianal region. It frequently occurs in families with children.

Otherwise, this is the typical and almost only type of severe vulvitis in prepubertal girls. Occasionally, there may be a whitish irregular coating (exfoliated epithelial cells) and red nodules (Figs. 7.22, 7.26). A fungal infection is therefore often considered initially, thus delaying proper treatment. Ischuria may occur if there is pronounced inflammation and pain. The infection may occur repeatedly in families at risk.

Fig. 7.22 Vulvitis caused by group A streptococci in a six-year-old girl. This form of vulvitis is typical for children. Transmission most likely occurs by means of the fingers from the frequently colonized nasopharyngeal space to the genitals.

Fig. 7.23 Large abscess of the right labium majus in a six-year-old girl.

Widespread inflammation with redness reaching to the anus and without a pathogen visible under the microscope is typical for, or prompt the suspicion of, an infection with group A streptococci (Fig. 7.27).

Diagnosis:

Microscopy. Wet mounts in 0.1% methylene blue solution show plenty of granulocytes and cocci (Fig. 7.28).

Microscopy. Wet mounts in 0.1% methylene blue solution show plenty of granulocytes and cocci (Fig. 7.28).

Culture

Culture

Fig. 7.24 Recurrent vulvovaginitis and perianal dermatitis caused by group A streptococci in a 30-year-old patient with two children.

Fig. 7.26 Perianal dermatitis and vulvitis caused by group A streptococci in a three-year-old girl.

Fig. 7.27 Pronounced vulvitis caused by group A streptococci in a 38-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.28 Micrograph illustrating vulvitis caused by group A streptococcus in a six-year-old girl. The swab material taken from the vulva and stained with methylene blue contains numerous cocci in addition to masses of granulocytes.

Fig. 7.29 Pyoderma affecting the finger of a 58-year-old patient suffering simultaneously from malaise, dermatitis, and vulvitis caused by group A streptococci.

Antibiogram, (normally not necessary as resistances are rare).

Antibiogram, (normally not necessary as resistances are rare).

Therapy. Penicillin, amoxicillin, or cephalosporin for 10 days.

Differential diagnosis. Candidiasis, plasma cell vulvitis, trichomoniasis, atrophic vaginitis.

Special risks. Systemic spreading and the transmission to other persons endanger pregnant women, in particular, because of the perils of puerperal sepsis (see p. 218).

Group A streptococci are the most dangerous bacteria in the genital region.

Impetigo Contagiosa

Caused by group A streptococci, this infection of the skin is almost exclusively seen in children.

Occasionally, it may occur also in women. Group A streptococci are among the most dangerous pathogens in the genital region. There is always the risk of introducing them into the genital region from other sites of the body, especially when fingers are infected (Fig. 7.29).

Erysipelas

Clinical picture. This acute superficial skin infection is caused by group A streptococci and, less often, by group G streptococci. The pathogens usually enter the body through small skin lesions. Apart from superficial, circumscribed, and painful redness of the skin (Fig. 7.30), the infection causes swelling of the regional lymph nodes as it is spreading through the lymph vessels. There may be fever, malaise, and also shaking chills.

Diagnosis. Diagnosis is based on the clinical picture, since the pathogen cannot be detected in the skin. Detection of group A streptococci from the nasopharyngeal cavity or the genitals may be helpful.

Therapy. Penicillin is administered orally for 10 days, and cephalosporins or macrolides are also an option.

Fig. 7.30 Erysipelas of the left hip (caused by group A streptococci) after vulvectomy and chronic lymphostasis.

Vulvitis Caused by Viruses

Genital Herpes

Genital herpes is among the most common infections of the genital region. The primary infection with herpes simplex virus is sexually transmitted. Its course is severe, unless there is immunity to herpes simplex virus due to a preceding oral infection. Relapses are much milder, but they may become a nuisance due to the frequency of their occurrence. Transmission of the virus to the newborn can lead to fatal infection.

The clinical picture varies and ranges from asymptomatic secretion of the virus to burning pain and, finally, to very painful and febrile vulvitis, vaginitis, and cervicitis. Lower abdominal pain similar to that of pelvic inflammatory disease may occur as well. The degree of discomfort depends on the frequency and extent of the local inflammatory reaction. Early therapy may prevent both. Because the relapses vary greatly with respect to frequency and symptoms, many recurring herpes attacks are not recognized as such. On the other hand, supposedly herpes virus-induced ulcers may be treated without success, thus leading to doubts regarding the therapy.

Pathogen. Genital herpes is caused by two pathogenic human herpesviruses. These are herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). The viral genome consists of a single molecule of linear double-stranded DNA. It is surrounded by a nucleocapsid that, in turn, is enclosed in a loose lipid-bilayer envelope. Between the nucleocapsid and the envelope is a tegument of amorphous material. The HSV-1 and HSV-2 genomes exhibit about 50% homology of their nucleotide sequences. Serologically, the two viruses can be distinguished by means of specific monoclonal antibodies against different nucleocapsid antigens and, in particular, antigens of the envelope. Humans seem to be the only natural reservoir of these viruses. HSV-1 is considered the oral type, which is found almost exclusively in nongenital regions, whereas HSV-2 is defined as the genital type.

Transmission and infectivity. The virus is transmitted from person to person through smear infection (direct contact infection). It is rarely transmitted through objects (indirect contact infection) because the virus is not stable. Nevertheless, it is possible in some patients.

Points of entry are the mucosae and small lesions in the keratinized skin. The amount of transmitted virus particles, the point of entry, and the immune status of the afflicted person determine the length of the incubation period and the severity of the disease.

Vesicles (small blisters) filled with virus particles are particularly infectious. Ulcers and erosions also set free many virus particles, and detection of the pathogen is possible from here. Even at the crust stage, the virus can still be detected in cultures or PCR.

Herpes viruses can be set free even when no lesions are visible—for example, in the regions of the cervix, urethra, and mouth—and thus may infect the sexual partner or the newborn. This seems to be the most common form of transmitting the infection to the sexual partner. Petting offers no safe protection from transmission, and a condom provides only partial protection because it does not cover the entire genital region.

Epidemiology. Antibodies to herpes simplex viruses are formed by 80–90 % of adults. About 20 % of adults carry antibodies to type 2. The primary infection by HSV-1 usually takes place in early childhood in the orofacial region at the border between skin and mucosa. The infection is transmitted through direct body contact, normally already in early childhood. About 50% of all children become infected with the virus and are then seropositive. Only rarely does the infection become clinically manifest (recurrent aphthous stomatitis [canker sore], herpes of the cornea). A second episode of infection begins postpubertal with intimate relationships. It is only now that also HSV-2 becomes evident epidemiologically. Up to 70–80% of adults possess antibodies against HSV-1 and up to 20–30% possess antibodies against HSV-2. Between HSV-1 and HSV-2 there is partial cross-immunity, which prevents the spreading of HSV-2. Up to 70–80% of genital herpes attacks are caused by HSV-2, and 20–30% are caused by HSV-1.

Today, HSV-1 is isolated in about 50% of clinically manifest primary infections. Our own studies during the last 10 years have shown that the portion of HSV-1-induced severe genital infections has increased. Of 55 patients with primary genital herpes who turned up for examination and from whom herpes simplex virus was cultured, type 1 was detected in 37 (67%) (unpublished data). However, this high portion of type 1 is not only connected with the increase of this type in the genital region, but also with the state of immunity of the patient. In women lacking immunity against type 1—namely, those who did not suffer from this infection during childhood—the primary infection with type 2 takes a much more severe course than in women with existing immunity against type 1.

The manifestation index of primary genital infection is not known precisely. It is estimated to be 20–30%.

Pathogenesis. During an active infection, the HSV of genital herpes penetrates along the sensory nerve tracts into the sacrospinal dorsal root ganglion, where is persists in a latent form after larger lesions (or just the primary inflammation) have healed. In this phase, no structural proteins of the virus can be detected in the neurons by molecular biology tests; only the genome and latency-associated regulatory proteins are present. Various stress factors can reactivate the latent infection into a virus-producing infection. Important stress factors include hormonal changes (menstruation-associated herpes), emotional stress (anger, exhaustion, lack of sleep), trauma, UV irradiation of the innervation segment of the mucocutaneous region, infections, and fever (herpes febrilis, also called cold sore or fever blisters).

Clinical picture. Only about 30% of cases of genital herpes are clinically clear and are recognized as such. About 20% do cause complaints but are misinterpreted by the patient—and sometimes also by the physician. Half of all genital herpes patients are more or less asymptomatic. Thus, the actual number of HSV-2-infected patients is, in fact, three times as high as one might assume based on the clinical experience.

The clinical picture is very characteristic, with the infection running its course relatively quickly and in defined stages. Development and duration may vary depending on whether it is a primary infection or relapse, on the one hand, and the state of the patient’s immunity, on the other.

We distinguish between two forms of genital herpes:

the primary infection caused by exogenous infection after sexual contact

the primary infection caused by exogenous infection after sexual contact

the relapse caused by endogenous reactivation of the persisting virus in the respective nerve ganglion.

the relapse caused by endogenous reactivation of the persisting virus in the respective nerve ganglion.

Primary Genital Herpes

Pathogens:

herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), 50–70% of patients

herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), 50–70% of patients

herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), 30–50% of patients.

herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), 30–50% of patients.

Transmission. Genital herpes is transmitted through sexual contact with mostly asymptomatic virus carriers, often also through oral–genital contact. Rarely, if at all, it is transmitted by means of objects or by using the same toilette.

Incubation period. Three to eight days, rarely longer (up to 14 days).

Clinical picture. Characteristic features include:

swelling of the vulva (Fig. 7.31)

swelling of the vulva (Fig. 7.31)

spreading of the vesicles over large areas of the genitals and adjacent skin (Figs. 7.32, 7.33)

spreading of the vesicles over large areas of the genitals and adjacent skin (Figs. 7.32, 7.33)

bilateral appearance of symptoms

bilateral appearance of symptoms

long persistence of lesions (up to three weeks)

long persistence of lesions (up to three weeks)

painful swelling of inguinal lymph nodes (Fig. 7.34), which occasionally persists longer than the efflorescence of the vulva, sometimes over many weeks and even months.

painful swelling of inguinal lymph nodes (Fig. 7.34), which occasionally persists longer than the efflorescence of the vulva, sometimes over many weeks and even months.

In addition, the rapid course of the first stages (within hours and a few days) is very typical:

painful swelling and redness of the vulva associated with initially small nodules

painful swelling and redness of the vulva associated with initially small nodules

quick transition to intraepithelial clear vesicles

quick transition to intraepithelial clear vesicles

vesicles becoming opaque and confluent (Fig. 7.35)

vesicles becoming opaque and confluent (Fig. 7.35)

transition to lesions, less often to ulcers that develop a red halo (Figs. 7.36, 7.37)

transition to lesions, less often to ulcers that develop a red halo (Figs. 7.36, 7.37)

crust stage and healing without the formation of scars.

crust stage and healing without the formation of scars.

Fig. 7.31 Primary genital herpes (HSV-1) in a 21 -year-old patient with severe swelling of the labia minora.

Fig. 7.32 Primary genital herpes (HSV-2) in a 25-year-old patient.

Fig. 7.33 Primary genital herpes in a 20-year-old patient after eight days of infection. Severe pain, dysuria, and swollen inguinal lymph nodes; no antibodies to herpesviruses, but isolation of HSV-2.

Some of the patients have systemic symptoms like fever, headaches, malaise, or pain in the muscles and lower back.

In patients who already have HSV-1 antibodies, usually due to an oral herpes infection suffered during childhood, local symptoms are less pronounced (Fig. 7.38) and systemic symptoms appear less frequently.

About 50 % of primary genital herpes infections are not diagnosed during the first visit to the doctor because, initially, there is only burning and pain, while vesicles or eruptions are not yet visible at this early stage. Occasionally, the early stage is confused with candidiasis (fungal infection; see Figs. 7.5, 7.6, p. 71).

The vagina (see Fig. 7.101, p. 115) and the vaginal part of the cervix (portio vaginalis) (see Figs. 7.143–7.146, p. 141) may be affected in addition to the vulva. Because of the tenderness of the sensitive vulvar region, using the speculum may initially not be an option if the lesions are severe. Extensive primary genital herpes in the vulvar region of a child is rare (Fig. 7.39) and only possible through smear infection from mother to child, or through sexual abuse.

Voiding problems in the context of primary genital herpes may be explained by the presence of herpes vesicles in the urethra.

Fig. 7.34 Swelling of the inguinal lymph nodes in a patient with primary genital herpes.

Fig. 7.35 Primary genital herpes (HSV-1) in a 20-year-old patient with opaque vesicles (pustules).

Fig. 7.37 Primary genital herpes of the vulva in a 42-year-old patient. The course of infection was quick and of medium severity; flat ulcers (greatly enlarged) already present after six days.

Fig. 7.38 Primary genital herpes (HSV-2) in a patient with partial immunity due to HSV-1.

Fig. 7.39 Primary genital herpes in a six-month-old girl, infected by the mother through oral contact.

Fig. 7.40 Discrete lesions of herpes labialis in the presence of pronounced primary genital herpes (HSV-1).

Note. Lesions in the mouth or on the face (Fig. 7.40) may occur during primary infection with HSV-1 in the genital region. Because these lesions cause little pain, they usually do not attract much attention and are not recognized as such. Meanwhile, we have repeatedly observed that it was possible to culture the identified virus from both regions.

Diagnosis. Extensive laboratory tests are not required in case of a typical clinical picture and sufficient experience. However, tests are essential in questionable cases and with insufficient clinical experience.

Detection of the pathogen from vesicles or erosions/ulcers is the most reliable means of establishing the diagnosis:

Culture and typing. Up to now, this is the detection method of choice because herpesviruses can be easily and quickly grown in cell cultures. If plenty of virus particles are present, the cell culture will be positive after 24 hours. If there are only a few virus particles, the cytopathic effect in the cell culture will take several days to occur. Confirmation of the diagnosis and determination of the virus type is done by subsequent fluorescence microscopy using type-specific immune sera.

Culture and typing. Up to now, this is the detection method of choice because herpesviruses can be easily and quickly grown in cell cultures. If plenty of virus particles are present, the cell culture will be positive after 24 hours. If there are only a few virus particles, the cytopathic effect in the cell culture will take several days to occur. Confirmation of the diagnosis and determination of the virus type is done by subsequent fluorescence microscopy using type-specific immune sera.

Direct antigen test. An immunofluorescence test for the detection of HSV is available. For this purpose, a swab taken from the base of the vesicle or ulcus is rolled onto a microscopic slide and then fixed with acetone or ethanol. This method has the advantage that cell cultures are not required and transport problems thus do not play a role since the sample is permanently preserved. However, the sensitivity of this test is only 80–95 % as compared with cell cultures. There are also enzyme tests available, which are slightly less sensitive.

Direct antigen test. An immunofluorescence test for the detection of HSV is available. For this purpose, a swab taken from the base of the vesicle or ulcus is rolled onto a microscopic slide and then fixed with acetone or ethanol. This method has the advantage that cell cultures are not required and transport problems thus do not play a role since the sample is permanently preserved. However, the sensitivity of this test is only 80–95 % as compared with cell cultures. There are also enzyme tests available, which are slightly less sensitive.

Molecular biology methods using DNA. The detection of viral DNA by means of hybridization is about as sensitive as the antigen test. DNA amplification tests (PCR) will be the method of the future. So far, these tests are used if herpes simplex encephalitis is suspected. For routine diagnosis, this method has not yet been established in practice.

Molecular biology methods using DNA. The detection of viral DNA by means of hybridization is about as sensitive as the antigen test. DNA amplification tests (PCR) will be the method of the future. So far, these tests are used if herpes simplex encephalitis is suspected. For routine diagnosis, this method has not yet been established in practice.

Serology. The detection of antibodies in the blood is neither suitable for diagnosis of primary genital herpes nor for recurrent genital herpes. It is, however, useful for determining the immune status or for distinguishing between primary infection and a relapse. In case of genital herpes relapse, IgM antibodies can be detected in the minority of patients; hence, serology is not very helpful. Up to now, many of the commercially available serological tests for distinguishing antibodies against HSV-1 and HSV-2 have not been meeting expectations.

Serology. The detection of antibodies in the blood is neither suitable for diagnosis of primary genital herpes nor for recurrent genital herpes. It is, however, useful for determining the immune status or for distinguishing between primary infection and a relapse. In case of genital herpes relapse, IgM antibodies can be detected in the minority of patients; hence, serology is not very helpful. Up to now, many of the commercially available serological tests for distinguishing antibodies against HSV-1 and HSV-2 have not been meeting expectations.

Therapy. Early systemic administration of antiviral substances is crucial. Treatment for at least five days is recommended. In individual patients, the dose will need to be increased and the duration of treatment prolonged as well.

In case of severe pain, additional administration of 100 mg diclofenac for the first one to three days once or twice per day is indicated. Topical application of anaesthetic ointments in the periurethral region one to two hours prior to voiding may facilitate passing urine.

Aciclovir (5 × 200 mg orally for at least five days) inhibits the multiplication of viruses (p. 46); when given early, pain will be alleviated relatively quickly (two to three days), which shows that the treatment is successful.

Aciclovir (5 × 200 mg orally for at least five days) inhibits the multiplication of viruses (p. 46); when given early, pain will be alleviated relatively quickly (two to three days), which shows that the treatment is successful.

Valaciclovir (orally 2 × 500 mg), the valine ester of aciclovir. After oral uptake, it is transformed quickly and almost completely to aciclovir and L-valine by valaciclovir hydrolase in the intestine and liver. This significantly improves the bioavailability of valaciclovir (54%) as compared with aciclovir.

Valaciclovir (orally 2 × 500 mg), the valine ester of aciclovir. After oral uptake, it is transformed quickly and almost completely to aciclovir and L-valine by valaciclovir hydrolase in the intestine and liver. This significantly improves the bioavailability of valaciclovir (54%) as compared with aciclovir.

Famciclovir (3 × 250 mg orally for at least five days).

Famciclovir (3 × 250 mg orally for at least five days).

Differential diagnosis:

candidiasis (confusion is only possible at an early stage, Fig. 7.6, p. 71)

candidiasis (confusion is only possible at an early stage, Fig. 7.6, p. 71)

folliculitis (S. aureus, see Fig. 7.15, p. 77)

folliculitis (S. aureus, see Fig. 7.15, p. 77)

plasma cell vulvitis (see Fig. 7.56, p. 93)

plasma cell vulvitis (see Fig. 7.56, p. 93)

skin lesion (see Fig. 7.94, p. 111)

skin lesion (see Fig. 7.94, p. 111)

toxic reaction (see Fig. 7.91, p. 110)

toxic reaction (see Fig. 7.91, p. 110)

irritable dermatitis (see Fig. 7.90, p. 110)

irritable dermatitis (see Fig. 7.90, p. 110)

Behçet syndrome (see Figs. 7.85, 7.86, p. 108).

Behçet syndrome (see Figs. 7.85, 7.86, p. 108).

Recurrent Genital Herpes

Pathogens:

herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), 80–90% of patients

herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), 80–90% of patients

herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), 10–20% of patients.

herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), 10–20% of patients.

Transmission. Recurrent genital herpes is not an exogenous infection but the endogenous reactivation of the virus and thus occurs independently of sexual contact.

Clinical picture. About 85% of patients with primary genital herpes will experience a symptomatic relapse. Characteristic are circumscribed groups of vesicles (Fig. 7.41), pustules and lesions (Figs. 7.42–7.44), or crusts (Fig. 7.45). Generalized symptoms occur less often than with the primary infection. This also applies to the swelling of regional lymph nodes and neuralgic symptoms. Relapse frequencies vary; depending on the HSV type, there may be 12 and more relapses per year, with HSV-2-induced relapses being more frequent than those induced by HSV-1.

The location of recurrent genital herpes symptoms may change from superior to inferior locations and from the front to the back (e. g., to the buttocks, Fig. 7.46), whereas the affected side of the body remains the same in most patients.

Deep lesions expanding over larger areas due to recurrent genital herpes occur only in the presence of immune suppression (Figs. 7.47, 7.48). In such patients, diagnosis is considerably hampered and can be established only by means of laboratory tests (detection of the virus and simultaneous detection of species-specific antibodies).

In contrast to the primary manifestation, herpes relapses in the genital region are preceded by prodromal symptoms, such as hyperesthesia, neuralgiform pain, and malaise. It is especially the recurrent herpes that causes serious emotional, sexual, and psychosocial conflicts within an existing partnership.