Hysteroscopic Surgery

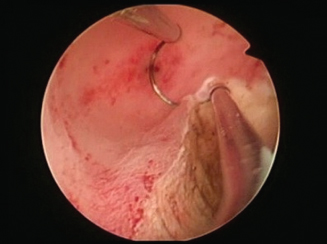

An operating hysteroscope is used in which small instruments are passed down a parallel channel. Using cutting diathermy and glycine irrigation fluid the endometrium (transcervical resection of endometrium [TCRE]; Fig. 15.2) or intracavity fibroids (transcervical resection of fibroid [TCRF]) and polyps are removed. If a uterine septum is present this can be resected up to the fundus of the cavity. The complications of uterine perforation and fluid overload are unusual with experienced surgeons. With TCRE and/or TCRF most patients have a significant reduction in blood loss. TCRE is best used with bleeding that is heavy but regular and not painful, in women approaching the menopause. Sterility is not ensured so sometimes a laparoscopic tubal sterilization is performed at the same time. Endometrial roller-ball diathermy, laser ablation or heating with an intrauterine hot balloon or microwave probe produce similar effects and may be safer but, because no specimen is produced, prior biopsies are essential.

Fig. 15.2 Transcervical resection of endometrium (TCRE). The monopolar cutting loop creates ‘trenches’ within the endometrium until it is completely removed.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

The peritoneal cavity is insufflated with carbon dioxide after carefully passing a small hollow Veress needle through the abdominal wall. This enables a sharp trocar to be inserted through the umbilicus with less risk of damaging organs or major blood vessels. A laparoscope is then passed down the trocar to enable visualization of the pelvis (Figs. 15.1 and 15.3). Laparoscopy is used to assess macroscopic pelvic disease in the management of pelvic pain and dysmenorrhoea, infertility (when dye is passed through the cervix to assess tubal patency: ‘lap and dye’), suspected ectopic pregnancy and pelvic masses.

Fig. 15.3 Laparoscopic photograph of a normal pelvis. The right ovary contains a 2-cm preovulatory follicle.

Laparoscopic Surgery

Instruments to grasp or cut tissue are inserted through separate ports in the abdominal wall. Laparoscopic surgery is commonly performed to sterilize, to remove adhesions or areas of endometriosis, or remove an ectopic pregnancy, but virtually every gynaecological operation has now been performed laparoscopically. The advantages are better visualization of tissues, less tissue handling, less infection, reduced hospital stay and faster postoperative recovery with less pain. However, serious visceral damage can occur, particularly in less experienced hands and/or with more complicated and extensive surgery.

Hysterectomy

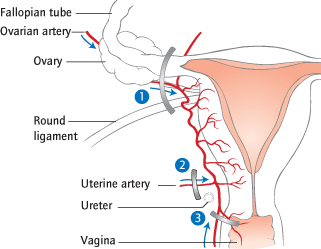

This is the most common major gynaecological operation (Fig. 15.4). The ovaries can also be removed (bilateral salpingo-oöphorectomy [BSO]). Hysterectomy is most commonly performed for menstrual disorders, fibroids, endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and prolapse; the treatment of pelvic malignancies also includes hysterectomy. Advances in medical management, e.g. of abnormal uterine bleeding (such as the intrauterine system [IUS]; [→ p.13]) should make the operation rarer and should be tried before this last resort.

Fig. 15.4 Hysterectomy. (1) Blood: the anastomosis between uterine and ovarian arteries. If the ovaries are removed the ovarian artery and vein are ligated instead. Ligament: the round ligament. (2) Blood: the main uterine artery. Ligament: the cardinal ligament. The bladder is first dissected off the cervix and upper vagina, to prevent injury to it or to the ureters, which are close. (3) Blood: the cervicovaginal branches of the uterine artery supplying the cervix and upper vagina. Ligament: the uterosacral ligament.

Types of Hysterectomy

Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) is removal of the uterus and cervix through an abdominal incision. The steps are performed from above, and therefore in the order 1, 2, 3 shown in Fig. 15.4. Specific indications include malignancy (ovarian and endometrial, in conjunction with a full laparotomy), a very large or immobile uterus and when abdominal inspection is required. In a subtotal hysterectomy, the cervix is retained and step 3 (Fig. 15.4) is omitted. This reduces the risk of damaging the ureters or bladder since less extensive dissection is required. However, the patient will need to continue with regular cervical smears, so is inappropriate if there is a history of abnormal smears. Some will continue to have menstrual spotting from small amounts of endometrium remaining in the cervical canal.

Vaginal hysterectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree