18.2 Glomerulonephritis, renal failure and hypertension

Haematuria

Glomerulonephritis

The clinical features of glomerulonephritis are:

• acute fluid overload – oedema, pulmonary oedema, congestive cardiac failure

• renal impairment – oliguria, raised plasma creatinine level.

Acute presentation with these clinical features is seen most commonly in post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. Other forms of glomerulonephritis in childhood may have a less severe onset (Box 18.2.1). Most forms of glomerulonephritis result from an immunologically mediated injury involving either deposition of circulating immune complexes in the glomerulus or a specific antibody to the glomerular basement membrane.

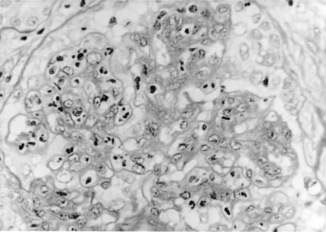

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

This disorder follows 7–14 days after group A β-haemolytic streptococcal throat infection and 3–6 weeks after streptococcal skin infection. It is hypothesized that streptococcal antigens deposit in glomeruli with activation of the complement system. The pathological appearance consists of proliferation of mesangial and endothelial cells with neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 18.2.1). Crescents may be present. Immunofluorescence shows IgG and C3, and electron-dense deposits (humps) are demonstrated by electron microscopy.

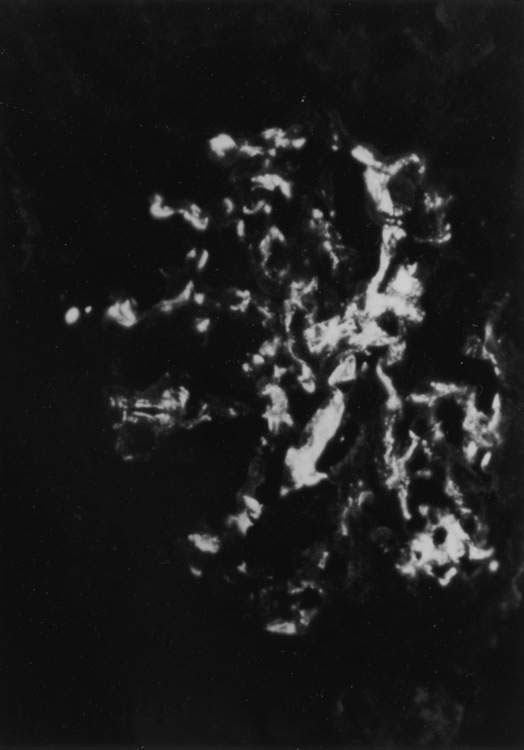

IgA nephropathy

This glomerulopathy is present in 50% of children who have recurrent episodes of macroscopic haematuria. The episodes of haematuria often occur simultaneously with intercurrent viral infections and may be associated with flank pain. Other presentations include abnormal urinalysis on medical examination and, rarely, an acute glomerulonephritis with renal failure. Renal biopsy shows a focal proliferative glomerulonephritis with IgA in the mesangium (Fig. 18.2.2). Although the prognosis for most children with IgA nephropathy is good, long-term studies show that about 10% progress to chronic renal failure by 15 years after onset of disease. Bad prognostic features include impaired renal function at presentation, heavy proteinuria and hypertension.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

This disease is a vasculitic illness involving predominantly small vessels in the skin, large joints and gastrointestinal tract (see Chapter 16.2). The illness is preceded by upper respiratory tract infection in 30–50% of patients. These children present with a petechial or purpuric rash that is localized over lower limbs and buttocks, abdominal pain and arthritis. A mild nephritis with microscopic haematuria and proteinuria is seen in 50–70% of cases. Rarely, blood pressure and serum creatinine levels are raised. Renal histology shows a proliferative glomerulonephritis with IgA in the mesangium. The prognosis is good, with less than 5% developing chronic kidney disease.

Lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presents in childhood in 20% of cases and is more common in children from Asian countries. Facial rash, arthritis and fever are common presenting symptoms. Serum C3 complement is usually low and anti-nuclear antibodies can often be detected, especially to double-stranded DNA. Renal biopsy is indicated if haematuria and proteinuria are present. The type of glomerular disease in SLE can vary from a mild focal proliferative glomerulonephritis to a diffuse crescentic glomerulonephritis. The treatment is complex but generally involves various combinations of immunosuppressant medications such as prednisolone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate. The amount of immunosuppression is dependent on clinical severity of kidney disease and renal histology. This disorder is discussed further in Chapter 13.3.

Proteinuria

Nephrotic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is defined as:

• proteinuria (> 40 mg per m2 per h or protein/creatinine ratio > 250 mg/mmol)

• hypoalbuminaemia (< 25 mg/dL)

The annual incidence in children is approximately 2–4 per 100 000. The major conditions associated with a primary nephrotic syndrome are listed in Box 18.2.2.

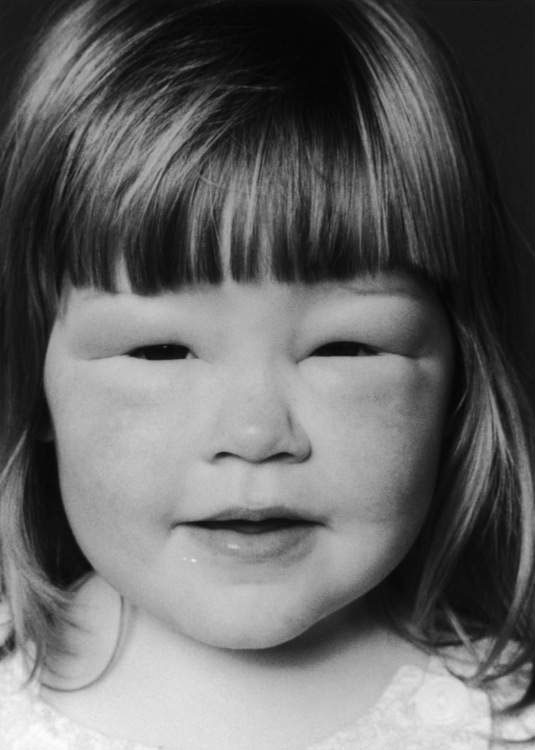

Minimal change nephrotic syndrome

The majority of children present between the ages of 1 and 4 years with generalized oedema (Fig. 18.2.3). Renal biopsy is not initially indicated if clinical features suggest minimal change disease (Box 18.2.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree