Amniotic fluid disorders (including oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios)

Intrauterine growth restriction Cervical insufficiency

Multiple gestation

Postterm pregnancy

Fetal demise in utero (FDIU)

Amniotic fluid volume (AFV) represents the balance between production and removal of fetal fluids.

In early gestation, fluid is produced from the fetal surface of the placenta, from transfer across the amnion, and from embryonic surface secretions.

In mid to late gestation, fluid is produced by fetal urination and alveolar transudate. By 16 weeks, there is about 250 mL of fluid, increasing to approximately 800 mL by 34 to 36 weeks’ gestation.

Fluid is removed by fetal swallowing and absorption at the amnion-chorion interface.

The most accurate measurement of AFV is by dye dilution techniques or direct measurement at the time of hysterotomy. Ultrasound provides a standard noninvasive tool to estimate AFV (Table 8-1).

Polyhydramnios is the pathologic accumulation of amniotic fluid defined as more than 2,000 mL at any gestational age, more than the 95th percentile for gestational age, or an amniotic fluid index (AFI) >25 cm at term.

The incidence of polyhydramnios in the general population is about 1%.

Implications: Mildly increased AFV is usually clinically insignificant. Markedly increased AFV is associated with increased perinatal morbidity due to preterm labor, cord prolapse upon membrane rupture, underlying comorbidities, and congenital malformations. Abruptio placentae is associated with polyhydramnios and rupture of membranes due to rapid decompression of the overdistended uterus. Increased maternal morbidity also results from postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine overdistention leading to atony. If polyhydramnios is severe, uterine distention can cause venous and ureteral compression causing severe lower extremity edema and hydronephrosis.

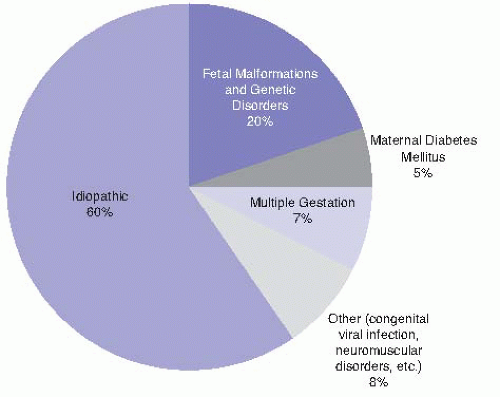

The most common etiology of polyhydramnios is idiopathic (Fig. 8-1); however, in severe cases, a cause is more often apparent and likely to be associated with a detectable fetal anomaly. Specific causes include:

Fetal structural malformations: In cases of acrania or anencephaly, polyhydramnios occurs from an impaired swallowing mechanism, low antidiuretic

hormone causing polyuria, and possibly transudation across the exposed fetal meninges. Gastrointestinal tract anomalies may also lead to polyhydramnios by either direct physical obstruction or decreased absorption. Ventral wall defects increase AFV from transudation across the peritoneal surface or bowel wall.

TABLE 8-1 Methods of Amniotic Fluid Assessment

Diagnostic Method

Interpretation

Clinical Value

Maximum vertical pocket (MVP)

Oligo ≤2 cm

Normal = 2.1-8 cm

Poly ≥8 cm

94% concordant with dye-determined normal pregnancies

Less accurate for low AFV

Useful predictor of adverse events

Amniotic fluid index (AFI)— measurement and summation of deepest pocket in each of four quadrants

Oligo <5 cm

Normal = 5.1-25 cm

Poly ≥25 cm

71%-78% concordant with dye-determined normals

Abnormal not highly predictive of adverse events

High false-positive rate

Subjective assessment— performed by experienced sonographer

Subjective result

65%-70% concordant with dye-determined normals

Very poorly identifies abnormal volumes

2 × 2 cm pocket— sonographic survey to verify at least one 2 × 2 cm fluid pocket

Evaluates for presence or absence of 2 × 2 cm pocket

98% concordant with dye-determined normals

Found in <10% of oligohydramnios

AFV, amniotic fluid volume.

Adapted and expanded from Moore TR. Clinical assessment of amniotic fluid. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1997;40(2):303-313.

Chromosomal and genetic abnormalities: As many as 35% of fetuses with polyhydramnios have chromosomal abnormalities. The most common are trisomies 13, 18, and 21.

Neuromuscular disorders: Impaired fetal swallowing can increase AFV.

Diabetes mellitus: Maternal diabetes mellitus is a common cause of polyhydramnios, especially with poor glycemic control or associated fetal malformations. Fetal hyperglycemia can increase fluid transudation across the placental interface and cause fetal polyuria.

Alloimmunization: Hydrops fetalis can increase AFV.

Congenital infections: In the absence of other factors, polyhydramnios warrants screening for congenital infections, such as toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and syphilis. These are, however, rare causes of polyhydramnios.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS): The recipient twin develops polyhydramnios and occasionally hydrops fetalis, whereas the donor twin develops growth restriction and oligohydramnios.

Ultrasound estimates AFV, identifies multiple gestations, and may detect fetal abnormalities. Amniocentesis for karyotype is offered if any anomalies are diagnosed.

Treatment is aimed at the underlying cause. Mild to moderate polyhydramnios can be managed expectantly until the onset of labor or spontaneous rupture of membranes. If the patient develops significant dyspnea, abdominal pain, or difficulty ambulating, treatment becomes necessary.

Amnioreduction can alleviate significant maternal symptoms. Amniocentesis is performed, and fluid is removed. Frequent removal of smaller volumes (total 1,500 to 2,000 mL or until the AFI is <8 cm) will result in a lower risk of preterm labor compared with removal of larger volumes. Amnioreduction is repeated every 1 to 3 weeks as needed. Antibiotic prophylaxis is unnecessary.

Pharmacologic treatment with indomethacin reduces fetal urine production. Fetal renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) are sensitive to prostaglandins. The cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (25 mg orally every 6 hours) can decrease fetal renal blood flow and urination. Premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus is a potential complication of indomethacin that requires close AFV and ductus diameter monitoring. Discontinue therapy if there is any suggestion of ductus closure. The risk of complications is low if the total daily dose of indomethacin is <200 mg, the treatment is limited to pregnancies <32 weeks, and the duration of therapy is <48 hours. In contrast, diuretics are ineffective as a treatment of polyhydramnios.

Oligohydramnios has multiple definitions, most commonly as a gestation with an AFI of <5 cm. Alternative definitions include less than the fifth percentile for gestational age or with a single maximum vertical pocket (MVP) of amniotic fluid of <2 cm. It is associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality at any gestational age, but the risks are particularly high during the second trimester when perinatal mortality approaches 80% to 90%. Pulmonary hypoplasia can result from insufficient fluid filling the terminal air sacs. Prolonged oligohydramnios in the second and third trimester leads to cranial, facial, or skeletal abnormalities in 10% to 15% of cases. Cord compression leads to increased incidence of fetal heart rate decelerations in labor.

The etiology of oligohydramnios includes ruptured membranes, fetal urinary tract malformations, postterm pregnancy, placental insufficiency, and medications reducing fetal urine production. Rupture of membranes must be considered at any gestational age. Renal agenesis or urinary tract obstruction often becomes apparent during the second trimester of pregnancy, when fetal urine flow begins to contribute significantly to AFV. Placental insufficiency can cause both oligohydramnios and intrauterine growth restriction. The cause of oligohydramnios in postterm pregnancies may be deteriorating placental function (Fig. 8-2).

Ultrasound is used to diagnose oligohydramnios. Rupture of membranes should be evaluated, and in cases of preterm gestation with uncertain membrane status, a tampon dye test can be performed (see Chapter 9).

Treatment for oligohydramnios is limited. Maternal intravascular fluid status appears to be closely tied to that of the fetus; maternal hydration (intravenous or oral) may improve the AFV depending on the etiology of oligohydramnios. In cases of obstructive genitourinary defects, in utero surgical diversion has produced

some promising results. For optimal benefit, urinary diversion must be performed before renal dysplasia develops and early enough in gestation to permit normal lung development. Until near term, oligohydramnios is managed with frequent fetal surveillance. Indications for induction of labor include term gestation or nonreassuring fetal testing after 34 weeks. Oligohydramnios is not a contraindication to labor. There is no consensus as to which of the measurements of AFV is most recommended when deciding if induction for oligohydramnios is indicated. MVP may be a superior option to AFI, as AFI measurement has a higher rate of false positives for oligohydramnios and thus increases induction and cesarean section rates without evidence of improvement in neonatal outcomes.

The etiology of IUGR includes both maternal and fetal causes:

Constitutionally small mothers and inadequate weight gain: Women who weigh <100 pounds at conception have double the risk for a small-for-gestational-age newborn. Inadequate or arrested weight gain after 28 weeks of pregnancy is also associated with IUGR. Underweight women should have a 28 to 40 pounds of weight gain during pregnancy.

Chronic maternal disease: Multiple medical conditions of the mother, including chronic hypertension, cyanotic heart disease, pregestational diabetes, malnutrition, and collagen vascular disease, can cause growth restriction. Preeclampsia and smoking are associated with IUGR.

Fetal infection: Viral causes including rubella, CMV, hepatitis A, parvovirus B19, varicella, and influenza are among the best known infectious antecedents of IUGR. In addition, bacterial (listeriosis), protozoal (toxoplasmosis), and spirochetal (syphilis) infections may be causative.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree