General Obstetric Care

Alexandra C. Spadola

Mary E. D’Alton

The goal of obstetric care is to support a woman, healthy or otherwise, through pregnancy with minimal risk to her own health and maximal benefit to the fetus. The challenge of modern obstetrics is to manage pregnancy, a normal physiologic process, with as little interference as possible, while identifying and treating complications that may arise. Risk factor screening and early recognition of complications allow for timely intervention, consultation with appropriate specialists, and, as indicated, transfer to tertiary centers with expert perinatology and neonatology staff. It must be stressed, however, that in obstetrics high-risk scenarios can develop rapidly and unexpectedly in the context of an otherwise normal labor and delivery. Every hospital delivering babies must be equipped to give adequate intrapartum care and must be prepared to perform a cesarean delivery within 30 minutes.

The broad spectrum of perinatal problems requires the full consideration of the medical and social factors that can affect the mother, fetus, and neonate. This awareness can be achieved by cooperative interaction between the mother, the obstetrician, the pediatrician, medical consultants, nurses, and social workers involved in perinatal care, as well as between the community and regional medical centers providing these services. Such collaborations afford the best opportunities for the goal of achieving healthy mothers and infants.

PRENATAL CARE

Prenatal care is an essential part of general obstetric care. Prenatal care ideally begins before conception with an assessment of obstetric risk factors and optimization of maternal health status. As recommended by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), women and their partners should be offered screening for genetic disorders specific to their ethnic background, such as the mutations for Tay-Sachs and cystic fibrosis. Common maternal diseases such as diabetes mellitus and chronic hypertension should be well controlled. Patients who require pharmacologic management of their medical conditions should be transitioned to regimens that are the least teratogenic. Women with severe medical problems such as heart disease or renal failure should be counseled as to their potential risks during pregnancy as well as the possible fetal complications. For example, a woman with pulmonary hypertension may face as high as 50% mortality with pregnancy; women with severe renal failure have high rates of preeclampsia and prematurity.

An important goal of prenatal care is the prevention of adverse fetal outcomes. Alcohol abuse in pregnancy is a leading cause of preventable developmental delay in the United States. Drinking has not clearly been demonstrated safe in any quantities and should be avoided. Tobacco and illicit drug use should cease. Proper nutrition and vitamin supplementation have been shown to reduce the incidence of congenital diseases. Women at high risk for having a fetus with a neural tube defect should be placed on high doses of folic acid even before conception. Similarly, the prenatal identification of women infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) allows for the administration of antiretroviral agents that have been shown to reduce the transmission of HIV to the fetus from 25% to 8%.

Prematurity continues to be the largest contributor to neonatal morbidity and mortality; prevention of preterm labor remains one of the most challenging aspects of obstetric care. Despite extensive research, history of prior preterm delivery remains the most powerful risk factor for premature birth, and minimal advances have been made in the management of preterm labor once it occurs. Over the last two decades the rise in the incidence of multiple gestations due to assisted reproductive techniques has contributed to the increase in low-birth-weight infants.

Perinatal mortality ranges from a low of 3 in 1,000 live births born to low-risk women with apparently normal fetuses to 145 in 1,000 live births born to women with high-risk pregnancies such as those with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Box 21.1

lists various high-risk perinatal conditions. The expanding field of prenatal diagnosis has lead to advances in the recognition of fetal disease. Box 21.2 lists some of the detectable pathologic conditions. The list of treatable diseases that can be diagnosed and managed in utero is much shorter (Box 21.3). For further discussion of prenatal diagnosis see Chapter 22. Consultation with or transfer of patient care to a specialist in maternal fetal medicine, also known as a perinatologist, can be invaluable in many high-risk pregnancies. The challenge of obstetric care is to properly identify those women with risk factors in a timely fashion so that interventions can be made to minimize potential adverse maternal and fetal effects.

lists various high-risk perinatal conditions. The expanding field of prenatal diagnosis has lead to advances in the recognition of fetal disease. Box 21.2 lists some of the detectable pathologic conditions. The list of treatable diseases that can be diagnosed and managed in utero is much shorter (Box 21.3). For further discussion of prenatal diagnosis see Chapter 22. Consultation with or transfer of patient care to a specialist in maternal fetal medicine, also known as a perinatologist, can be invaluable in many high-risk pregnancies. The challenge of obstetric care is to properly identify those women with risk factors in a timely fashion so that interventions can be made to minimize potential adverse maternal and fetal effects.

BOX 21.1 Identification of Perinatal Risk Situations

Maternal conditions

Maternal medical disease (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease)

Poor obstetric history (e.g., prior stillbirth)

Antepartum hemorrhage

Postterm gestation (greater than 42 weeks)

Prolonged rupture of membranes

Rhesus incompatibility

Low socioeconomic status

Maternal age younger than 16 years or older than 35 years

Maternal drug or alcohol abuse

Fetal conditions

Abnormal fetal presentation (e.g., breech)

Fetal growth retardation

Multiple pregnancy

Polyhydramnios

Oligohydramnios

Malformation

Conditions of labor and delivery

Preterm labor

Prolonged labor

Operative delivery (e.g., forceps delivery, vacuum extraction)

Prolapsed umbilical cord

BOX 21.2 Fetal Anomalies and Genetic Syndromes Amenable to Prenatal Diagnosis

Structural anomalies

Congenital heart disease

Ventral wall defects

Neural tube defects

Skeletal dysplasias

Renal agenesis

Gastrointestinal atresias

Diaphragmatic hernias

Cleft lip/palate

Genetic syndromes

Aneuploidy

Tay-Sachs disease

Cystic fibrosis

Sickle cell anemia

Gaucher disease

Niemann-Pick disease

Galactosemia

Homocystinuria

Maple syrup urine disease

Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

Footnote

This list is by no means complete. Advances in ultrasound and molecular genetics have allowed for an ever-growing number of genetic syndromes that can be diagnosed antenatally.

BOX 21.3 Potentially Treatable Fetal Conditions

Fetal anemia: red blood cell isoimmunization; parvovirus infection

Fetal thrombocytopenia: alloimmune thrombocytopenia

Fetal cardiac arrhythmias

Aqueductal stenosis

Bladder outlet obstruction

Twin–twin transfusion syndrome

Toxoplasmosis

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Sacrococcygeal teratoma

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung

Fetal chylothorax

Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

MATERNAL ADAPTATIONS TO PREGNANCY

Pregnancy is a normal physiologic condition, not an illness. However, the metabolic changes that occur during pregnancy affect every organ system. Not only can these alterations mimic symptoms of disease, but they can also significantly impact the assessment and management of illness during pregnancy. Understanding and recognizing these changes is crucial to the proper care of all pregnant patients.

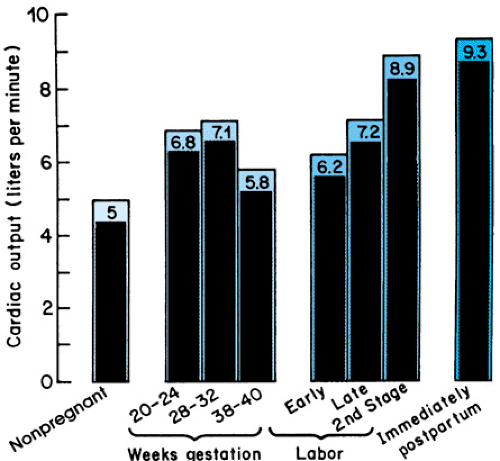

The cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy are profound. To provide sufficient blood flow to the uterus, and thus an adequate supply of nutrients to the growing fetus, uteroplacental blood flow reaches an astounding 500 to 700 mL/minute at term. The maternal cardiac output must increase by almost 50% to accommodate this added circulatory loop, and the maternal blood volume increases accordingly by 1.5 L (Fig. 21.1). This increased blood volume is accompanied by a similar, though slightly smaller, increase in the circulating red blood cell mass, leading to what is referred to as the physiologic anemia of pregnancy. The iron requirements for this degree of red blood cell production are substantial—approximately 1 g of elemental iron for an entire pregnancy—and make pregnant women prone to iron deficiency. Supplemental iron is recommended, especially during the third trimester.

Maternal renal function is augmented as early as the first trimester with increases in the glomerular filtration rate and renal plasma flow that parallel the increases in cardiac output. A resulting decrease in serum creatinine and urea nitrogen levels can be observed. This can lead to increased dosage requirements to achieve therapeutic drug levels for medications excreted via the kidneys.

The production of high levels of progesterone by the placenta leads to changes in the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and renal systems. Progesterone causes relaxation of smooth muscle, which induces slowing of the entire gastrointestinal tract, increasing gastric emptying times, symptomatic reflux, and constipation. The ureters become physiologically dilated, leading to urinary stasis and an increased risk of urinary tract infection. Central stimulation of the respiratory center by progesterone is responsible for the slight respiratory alkalosis and compensatory metabolic acidosis observed in pregnant women. In addition to mechanical changes of the thorax and an increase in intra-abdominal contents, this hormonal effect contributes to the mild dyspnea many pregnant women experience.

The placenta also produces human placental lactogen, a polypeptide homologous to human growth hormone. Its metabolic effects include an increase in lipolysis and the release of free fatty acids as well as the induction of a relatively “diabetogenic” state, with insulin resistance in the maternal tissues ensuring a continuous supply of glucose to the developing fetus. Women who are at baseline elevated risk for type 2 diabetes due to ethnic background, age, or body mass index may not be able to compensate for these changes and will develop gestational diabetes during the latter half of pregnancy.

LABOR AND DELIVERY

Normal Labor and Delivery

The intelligent management of labor rests on an understanding of its mechanics and normal progression. Labor is defined as the onset of regular uterine contractions accompanied by progressive dilation and effacement of the cervix and descent of the fetal presenting part. In the 1950s, Friedman began to study the labors of large numbers of women and published his now famous curve, which graphs cervical dilation as a function of time (Fig. 21.2). It has been the convention to divide this curve into three parts, or stages:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree