Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Infants With Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal (GE) reflux is common in young infants and is a physiological event. Frequent postprandial regurgitation, ranging from effortless to forceful, is the most common infant symptom. Infant GER is usually benign, and it is expected to resolve by 12–18 months of life.

Reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus occurs during spontaneous relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter that are unaccompanied by swallowing. Low pressures in the lower esophageal sphincter or developmental immaturity of the sphincter are not causes of GER in infants. Factors promoting reflux in infants include small stomach capacity, frequent large-volume feedings, short esophageal length, supine positioning, and slow swallowing response to the flow of refluxed material up the esophagus. Infants’ individual responses to the stimulus of reflux, particularly the maturity of their self-settling skills, are important factors determining the severity of reflux-related symptoms.

An important point in evaluating infants with GER is to determine whether the vomited material contains bile. Bile-stained emesis in an infant requires immediate evaluation as it may be a symptom of intestinal obstruction (malrotation with volvulus, intussusception).

Other symptoms may be associated with GERD in infants, although these situations are far less common than benign, physiologic GER. These clinical presentations include failure to thrive, food refusal, pain behavior, GI bleeding, upper or lower airway-associated respiratory symptoms, or Sandifer syndrome.

B. Older Children With Reflux

GERD is diagnosed when reflux causes persistent symptoms with or without inflammation of the esophagus. Older children with GERD complain of adult-type symptoms of regurgitation into the mouth, heartburn, and dysphagia. Esophagitis can occur as a complication of GERD and requires endoscopy with biopsy for diagnostic confirmation. Children with asthma, cystic fibrosis, developmental handicaps, hiatal hernia, and repaired tracheoesophageal fistula are at increased risk of GERD and esophagitis.

C. Extraesophageal Manifestations of Reflux Disease

GERD is implicated in the pathogenesis of several disorders unrelated to inherent esophageal mucosal injury. In infants, GERD has been linked to the occurrence of apnea or apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs), although the majority of pathologic cases are not reflux associated. Upper airway symptoms (hoarseness, sinusitis, laryngeal erythema, and edema), lower airway symptoms (asthma, recurrent pneumonia, recurrent cough), dental erosions, and Sandifer syndrome have all been linked to GERD, although proof of cause-and-effect relationship in many clinical circumstances can be challenging.

D. Diagnostic Studies

History and physical examination alone should help differentiate infants with benign, recurrent vomiting (physiologic GER) from those who have red flags for GERD or other underlying primary conditions that may present with recurrent emesis at this age. Warning signs that warrant further investigation in the infant with recurrent vomiting include bilious emesis, GI bleeding, onset of vomiting after 6 months, failure to thrive, diarrhea, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal tenderness or distension, or neurologic changes. Infants with suspected physiologic GER do not require further evaluations unless there is clinical concern for complicated GERD or nonreflux diagnoses.

An upper GI series should be considered when anatomic etiologies of recurrent vomiting are considered, but should not be considered to be a test for GERD.

In older children with heartburn or frequent regurgitation, a trial of acid-suppressant therapy may be both diagnostic and therapeutic. If a child has symptoms requiring ongoing acid suppressant therapy, or if symptoms fail to improve with empiric therapy, consider referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist to assist in evaluation for complicated GERD, or nonreflux diagnoses including eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

Esophagoscopy and mucosal biopsies are useful to evaluate for mucosal injury secondary to GERD (Barrett esophagus, stricture, erosive esophagitis), or to evaluate for nonreflux diagnoses that present with reflux-like symptoms, including EoE. Endoscopic evaluation is not requisite for the evaluation of all infants and children with suspected GERD.

Intraluminal esophageal pH monitoring (pH probe) and combined multiple intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (pH impedance probe) are indicated to quantify reflux, and to evaluate for objective evidence of symptom associations with regards to atypical reflux presentations. pH probe studies quantify esophageal acid exposure, and pH impedance studies also add detection of bolus fluid transit, including both acidic and nonacidic reflux. pH impedance studies in particular may have higher diagnostic yield in evaluating for respiratory or atypical complications of reflux disease, or in evaluating for breakthrough reflux symptoms while a patient is on acid-suppressant therapy.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Reflux resolves spontaneously in 85% of affected infants by 12 months of age, coincident with assumption of erect posture and initiation of solid feedings. Until then, regurgitation volume may be reduced by offering small feedings at frequent intervals and by thickening feedings with rice cereal (2–3 tsp/oz of formula). Prethickened “antireflux” formulas are available. In infants with unexplained crying/fussy behavior, there is no evidence to support empiric use of acid suppression.

Acid suppression may be used to treat suspected esophageal or extraesophageal complications of acid reflux in infants and older children. Therapeutic options include histamine-2 (H2)–receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). PPI therapy has been shown to significantly heal both esophageal mucosal injury and symptoms from GERD within an 8- to 12-week period. There is no sufficient evidence to support the routine use of prokinetic agents for treatment of pediatric GERD.

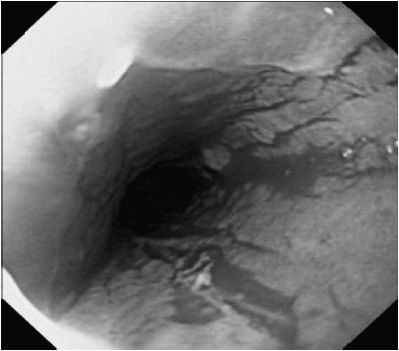

Spontaneous resolution is less likely in older children with GERD. In addition, children with underlying neurodevelopmental disorders are at risk for persistent GERD. Episodic symptoms may be controlled with intermittent use of acid blockers. Patients with persistent symptoms may require chronic acid suppression. Complications of reflux esophagitis or chronic GERD include feeding dysfunction, esophageal stricture, and anemia (see Figure 21-1). Barrett esophagus, a precancerous condition, is uncommon in children, but it may occur in patients with an underlying primary diagnosis that offers high risk for GERD.

Figure 21–1. Esophagitis associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mucosa is erythematous with loss of vascular pattern.

Figure 21–1. Esophagitis associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mucosa is erythematous with loss of vascular pattern.

Antireflux surgery (Nissen fundoplication) may be considered in a child with GERD who (1) fails medical therapy (2) is dependent on persistent, aggressive medical therapy, (3) is nonadherent to medical therapy, and (4) has persistent, severe respiratory complications of GERD or other life-threatening complications of GERD. Potential complications after antireflux surgery include dumping syndrome, gas bloat syndrome, persistent retching/gagging, or wrap failure.

Sherman PM et al: A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol 2009 May;104(5):1278–1295 [PMID: 19352345].

Vandenplas Y et al: Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009 Oct;49(4):498–447 [PMID: 19745761].

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

This recently recognized entity occurs in all ages and most frequently affects boys. Common initial presentations in young children include feeding dysfunction and vague nonspecific symptoms of GERD such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and regurgitation. If a history of careful and lengthy chewing, long mealtimes, washing food down with liquid or avoiding highly textured foods is encountered, one may suspect EoE. In adolescent’s symptoms of solid food dysphagia, heartburn and acute and recurrent food impactions predominate. If a child’s symptoms are unresponsive to medical and/or surgical management of GERD, EoE should be strongly considered as a diagnostic possibility. A family or personal history of atopy, asthma, dysphagia, or food impaction is not uncommon.

B. Laboratory Findings

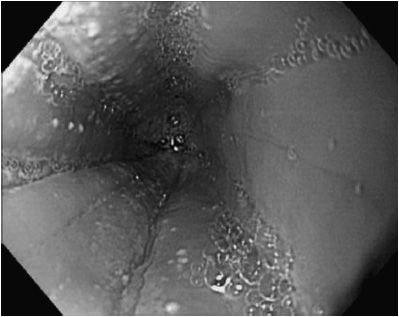

Peripheral eosinophilia may or may not be present. The esophageal mucosa usually appears abnormal with features of thickening, longitudinal mucosal fissures, and circumferential mucosal rings. The esophagus is often sprinkled with pinpoint white exudates that superficially resemble Candida infection. On microscopic examination the white spots are composed of eosinophils (Figure 21–2). Basal cell layers of the esophageal mucosa are hypertrophied and infiltrated by eosinophils (usually > 15/40 × light microscopic field). A lengthy stricture may be seen, which can split merely with the passage of an endoscope. Serum IgE may be elevated, but this is not a diagnostic finding. Specific allergens can often be identified by skin testing, and patient can sometimes identify foods that precipitate pain and dysphagia.

Figure 21–2. Esophagitis associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosa contains linear folds, white exudate, and has loss of vascular pattern.

Figure 21–2. Esophagitis associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Mucosa contains linear folds, white exudate, and has loss of vascular pattern.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The most common differential conditions are peptic esophagitis, congenital esophageal stricture, and Candidal esophagitis. EoE may be part of a generalized eosinophilic gastroenteropathy, a very rare, steroid-responsive entity. Patients with eosinophilic gastroenteropathy can also present with gastric outlet obstruction or intestinal caused by large local infiltrates of eosinophils in the antrum, duodenum, and cecum.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of EoE is based on clinical and histopathological features. Symptoms referable to esophageal dysfunction must be seen in association with esophageal eosinophilia and a normal gastric and duodenal mucosa. Other causes for esophageal eosinophilia, in particular, GERD, must be ruled out.

Treatment

Treatment

Dietary exclusion of offending allergens (elemental diet, removal of allergenic foods) is effective treatment. Such diets are useful in young children, but adherence in older children can be difficult. Topical corticosteroids also offer an effective treatment choice. Steroids are puffed in the mouth and swallowed from a metered dose pulmonary inhaler; this method of administration is completely opposite of how topical steroids are administered for the treatment of asthma. Two puffs of fluticasone from an inhaler twice daily using an age-appropriate metered dose is a common recommendation. Patients should not rinse their mouth or eat for 30 minutes to maximize the effectiveness. Systemic corticosteroids benefit most patients with more acute or severe symptoms. Esophageal dilation may be required to treat strictures. The association of EoE and esophageal malignancy has not been identified. Parent and family support is available at American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders APFED.org.

Liacouras CA et al: Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:3–20 [PMID: 21477849].

Mukkada V, Haas A, Creskoff N, Fleischer D, Furuta GT, Atkins D: Feeding dysfunction in children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Pediatrics 2010;126:e672–e677 [PMID: 20696733].

ACHALASIA OF THE ESOPHAGUS

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Achalasia most commonly occurs in children who are older than 5 years, but cases during infancy have been reported. Common symptoms in one recent study were emesis (84.6%), dysphagia (69.2%), weight loss (46.0%), and chronic cough (46.1%). Patients may eat slowly and often require large amounts of fluid when ingesting solid food. Dysphagia is relieved by repeated forceful swallowing or vomiting. Familial cases occur in Allgrove syndrome (alacrima, adrenal insufficiency, and achalasia, associated with a defect in the AAAS gene on 12q13, encoding the ALADIN protein) and familial dysautonomia. Though no genetic or pathophysiologic basis has been identified, there have been recent case reports of achalasia in pediatric autism patients. Chronic cough, wheezing, recurrent aspiration pneumonitis, anemia, and poor weight gain are common.

B. Imaging and Manometry

Barium esophagram shows a dilated esophagus with a tapered “beak” at the GE junction. Esophageal dilation may not be present in infants because of the short duration of distal obstruction. Fluoroscopy shows irregular tertiary contractions of the esophageal wall, indicative of disordered esophageal peristalsis. Achalasia has also been identified incidentally in patients undergoing GE scintigraphy. Esophageal manometry classically shows high resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter, failure of sphincter relaxation after swallowing, and abnormal esophageal peristalsis, though these findings may be sporadic, with some partial or normal relaxations present in some swallows. High-resolution manometry testing in adult patients suggests varying subtypes of achalasia, which may predict likelihood of response to different therapies.

C. Differential Diagnosis

Congenital or peptic esophageal stricture, esophageal webs, and esophageal masses may mimic achalasia. EoE commonly presents with symptoms of dysphagia and food impaction, similar to achalasia. Cricopharyngeal achalasia or spasm is a rare cause of dysphagia in children, but it shares some clinical features of primary achalasia involving the lower esophageal sphincter. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b, systemic amyloidosis, and postvagotomy syndrome cause esophageal dysmotility and symptoms similar to achalasia. Teenage girls may be suspected of having an eating disorder. In Chagas disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, nNOS and ganglion cells are diminished or absent in the muscular layers of the lower esophageal sphincter causing an acquired achalasia.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin paralyzes the lower esophageal sphincter and temporarily relieves obstruction but has relapse rates of greater than 50%. Pneumatic dilation of the lower esophageal sphincter produces temporary relief of obstruction that may last weeks to years. Pediatric trials are limited, but a recent single center experience of endoscopic dilation showed a long-term success rate of up to 87% with one to three dilations. Because of concerns that dilation may increase inflammation between the esophageal mucosal and muscular layers, however, some have advocated surgical myotomy as the best initial treatment. While, long-lasting functional relief is achieved by surgically dividing the lower esophageal sphincter (Heller myotomy), recurrence risk of obstructive symptoms following myotomy in children has been reported to be as high as 27%. Postoperative GERD is common, leading some to perform a fundoplication or place diaphragm valves at the same time as myotomy. In adult achalasia, per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has been increasingly utilized as a less invasive alternative to surgical treatment, with isolated case reports in children. In a large retrospective pediatric study, general response rates of pneumatic dilation compared to Heller myotomy were not significantly different, though recent studies suggest that children over 6 may have better outcomes with pneumatic dilation. Self-expanding metal stents have been used with success in adults with achalasia but have not been studied in children.

Because of the shorter duration of esophageal obstruction in children, there is less secondary dilation of the esophagus. Thus, the prognosis for return or retention of some normal esophageal motor function after surgery is better than in adults.

Arun S, Senthil R, Bhattacharya A, Thapa BR, Mittal BR: Incidental detection of pediatric achalasia cardia during gastroesophageal scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med 2013 Mar;38(3):228–229 [PMID: 23357819].

Betalli P et al: Autism and esophageal achalasia in childhood: a possible correlation? Report on three cases. Dis Esophagus 2012 May 6(3):237–240 [PMID: 22607127].

Di Nardo G et al: Pneumatic balloon dilation in pediatric achalasia: efficacy and factors predicting outcome at a single tertiary pediatric gastroenterology center. Gastrointest Endosc 2012 Nov;76(5):927–932 [PMID: 22921148].

Hallal C et al: Diagnosis, misdiagnosis, and associated diseases of achalasia in children and adolescents: a twelve-year single center experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2012 Dec;28(12):1211–1217 [PMID: 23135808].

Maselli R et al: Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) in a 3-year-old girl with severe growth retardation, achalasia, and Down syndrome. Endoscopy 2012;44(Suppl 2 UCTN):E285–E287 [PMID: 22933258].

Morera C, Nurko S: Heterogeneity of lower esophageal sphincter function in children with achalasia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012 Jan;54(1):34–40 [PMID: 21694632].

Zhou HB et al: Diaphragm valves reduce gastroesophageal reflux following cardiomyotomy for patients with achalasia. Acta Chir Belg 2012 Jul–Aug;112(4):287–291 [PMID: 23008993].

CAUSTIC BURNS OF THE ESOPHAGUS

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Ingestion of caustic solids or liquids (pH < 2 or pH > 12) produces esophageal lesions ranging from superficial inflammation to deep necrosis with ulceration, perforation, mediastinitis, or peritonitis. Acidic substances typically lead to limited injury because of the small volume ingested due to the sour taste. In addition, acid ingestions often lead to superficial coagulative necrosis with eschar formation. Conversely, the more benign taste of alkali ingestions may allow for larger volume ingestions, subsequent liquefactive necrosis that can lead to deeper mucosal penetration. Beyond the pH, factors that determine the severity of injury from a caustic ingestion include the amount ingested, the physical state of the agent, and the duration of mucosal exposure time. For these reasons, powdered or gel formulations of dishwashing detergent are especially dangerous, because of their innocuous taste, high pH, and tendency to stick to the mucosa. Symptoms of hoarseness, stridor, and dyspnea suggest associated airway injury, while odynophagia, drooling, and food refusal are typical with more severe esophageal injury. The lips, mouth, and airway should be examined in suspected caustic ingestion, although up to 12% of children without oral lesions can have significant esophageal injury.

B. Imaging Studies

Esophagoscopy is often a routine part of the evaluation in caustic ingestions to determine the severity and extent of the esophageal injury. Timing of endoscopy is important, however, as endoscopy may not indicate the true severity of injury if it is performed too early (< 24–48 hours) and may increase the risk of perforation if it is performed too late (> 72 hours) due to formation of granulation tissue. Grading of esophageal lesions into first degree (superficial injury, erythema only), second degree (transmucosal with erythema, ulceration, and sloughing), and third degree (transmural with circumferential sloughing and deep mucosal ulceration) can help predict prognosis. Circumferential lesions should be particularly noted, since they carry the highest risk of stricture formation. In a recent large single-center study, 34% of over 200 ingestions in children were grade 2 or 3, with 50% of these eventually requiring one or more endoscopic dilations for stricture formation. If dilation is felt to be necessary, it should not be performed in the acute phase of injury. Elevation of white blood cell count was found in a recent pediatric study to be a sensitive, but not specific, indicator of high-grade injury. In addition, despite the lack of clinical findings, esophageal lesions have been found in up to 35% and gastric lesions in up to 14% of patients. Because of the relative lack of good prognostic indicators of significant injury, most clinical guidelines recommend endoscopic evaluation as part of standard management in pediatric caustic ingestions. Plain radiographs of the chest and abdomen may be performed if there is clinical suspicion of perforation. Contrast studies of the esophagus should be performed when endoscopic evaluation is not available, as they are unlikely to detect grades 1 and 2 lesions. Some centers have advocated conservative management with upper GI series within 3 weeks of injury, reserving endoscopic evaluation for those with evidence of stricture.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Clinical observation is always prudent, as it is often difficult to predict the severity of esophageal injury at presentation. Vomiting should not be induced and administration of buffering agents should be avoided to prevent an exothermic reaction in the stomach. Intravenous corticosteroids (eg, methylprednisolone, 1–2 mg/kg/d) are given immediately to reduce oral swelling and laryngeal edema. Many centers advocate continued corticosteroids for the first week to decrease the risk of stricture formation; however, meta-analysis has not been able to show a clinical benefit from this practice. Intravenous fluids are necessary if dysphagia prevents oral intake. Treatment may be stopped if there are only first-degree burns at endoscopy. Whereas speculation suggest that broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage with third-generation cephalosporins may decrease stricture formation by preventing bacterial colonization into necrotic tissue, the use of antibiotics in cases of perforation is mandatory. Acid-blockade is often used to decrease additional injury from acid reflux.

Esophageal strictures develop in areas of anatomic narrowing (thoracic inlet, GE junction, or point of compression where the left bronchus crosses the esophagus), where contact with the caustic agent is more prolonged. Strictures occur only with full-thickness esophageal necrosis and prevalence of stricture formation varies from 10% to 50%. Shortening of the esophagus is a late complication that may cause hiatal hernia. Repeated esophageal dilations may be necessary as a stricture develops, with one review showing 35% requiring more than seven dilations. In that series of 175 patients, there was long-term success in only 16% of patients, with 4.5% having complications of perforation and a 2.8% mortality rate. In complicated cases esophageal stenting may be beneficial during early management. Newer, fully covered, self-expanding, removable esophageal stents, now available in pediatric sizes, may offer additional options for recurrent caustic strictures. Alternatively, in a multicenter analysis, endoscopic administration of topical mitomycin-C was effective in treatment of refractory caustic strictures of the esophagus. Animal models utilizing 5-fluorouricil in the early management of caustic esophageal injuries have also shown promise in preventing fibrosis and stricture formation. Surgical replacement of the esophagus by colonic interposition or gastric tube may be needed for long strictures resistant to dilation.

Contini S, Scarpignato C, Rossi A, Strada G: Features and management of esophageal corrosive lesions in children in Sierra Leone: lessons learned from 175 consecutive patients. J Pediatr Surg 2011 Sep;46(9):1739–1745 [PMID: 21929983].

Duman L et al: The efficacy of single-dose 5-fluorouracil therapy in experimental caustic esophageal burn. J Pediatr Surg 2011 Oct;46(10):1893–1897 [PMID: 22008323].

Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi T et al: Conservative management of caustic substance ingestion in a pediatric department setting, short-term and long-term outcome. Dis Esophagus 2011 Feb;24(2):86–91 [PMID: 20659141].

Kaya M, Ozdemir T, Sayan A, Arikan A: The relationship between clinical findings and esophageal injury severity in children with corrosive agent ingestion. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2010 Nov;16(6):537–540 [PMID: 21153948].

Temiz A, Oguzkurt P, Ezer SS, Ince E, Hicsonmez A: Predictability of outcome of caustic ingestion by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in children. World J Gastroenterol 2012 Mar;18(10): 1098–1103 [PMID: 22416185].

FOREIGN BODIES IN THE ALIMENTARY TRACT

Older infants and toddlers engage their environment, in part, by placing items in their mouth. As a result, foreign body ingestions are a common occurrence in pediatrics. Fortunately, 80%–90% of foreign bodies pass spontaneously with only 10%–20% requiring endoscopic or surgical management. At presentation the most common symptoms of an ingested foreign body are dysphagia, odynophagia, drooling, regurgitation, and chest or abdominal pain. Respiratory symptoms, such as cough, become prominent for foreign bodies retained in the esophagus for more than 1 week. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for toddlers presenting with these symptoms, even without a witnessed ingestion. If the ingestion is witnessed, the timing of the event is important to note as it will have implications for the timing of any necessary endoscopic procedures for removal.

The most common foreign body ingested by children is the coin (Figure 21–3). Ingested foreign bodies tend to lodge in narrowed areas—valleculae, thoracic inlet, GE junction, pylorus, ligament of Treitz, and ileocecal junction, or at the site of congenital or acquired intestinal stenoses. The evaluation of a swallowed foreign body starts with plain radiography. Radio-opaque objects will be easily visualized. Non–radio-opaque objects, such as plastic toys, may not appear on standard radiograph. If there is particular concern, based on patient symptoms, for a retained esophageal foreign body that is non–radio-opaque, a contrast esophagram is a useful test. Use of contrast, however, may delay or increase the risk of anesthesia due to aspiration concerns.

Figure 21–3. Foreign body in esophagus. Coin is lodged in the esophageal lumen.

Figure 21–3. Foreign body in esophagus. Coin is lodged in the esophageal lumen.

Esophageal foreign bodies should be removed within 24 hours to avoid ulceration, which can lead to serious complications such as erosion into a vessel or stricture formation. Disk-shaped button batteries lodged in the esophagus are especially concerning and should be removed immediately. Button batteries may cause an electrical thermal injury in as little as 2 hours and have resulted in death from subsequent aortoenteric fistula formation, even weeks after battery removal. Button batteries in the stomach will generally pass uneventfully, but they should be monitored closely to ensure prompt passage. With larger batteries (> 20 mm) and in younger children (< 5 years of age) endoscopic evaluation with gastric batteries may still be considered in order to evaluate the esophagus for signs of injury and risk of aortoesophageal fistula. Rates of significant injury and death due to swallowed button batteries have increased in recent years with the transition toward production of higher-voltage lithium batteries.

Esophageal food impaction should always raise the question of underlying esophagitis. In particular, EoE has been shown to be present in up to 75% of pediatric patients presenting initially with esophageal food impaction.

Smooth foreign bodies in the stomach, such as buttons or coins, may be monitored without attempting removal for up to several months if the child is free of symptoms. Straight pins, screws, and nails are examples of objects with a blunt end that is heavier than the sharp end. These asymmetrically weighted objects will generally pass without incident and so need for endoscopic removal must be considered on a case-by-case basis. In contrast, double-sided sharp objects that are weighted equally on each end, such as fishbones and wooden toothpicks, should be removed as they can migrate through the wall of the GI tract into the pericardium, liver, and inferior vena cava. Large, open safety pins should be removed from the stomach because they may not pass the pyloric sphincter and may cause perforation. Objects longer than 5 cm may be unable to pass the ligament of Treitz and should be removed. Magnets require consideration for removal only if there has been more than one ingested, or if a single magnet was ingested along with a metallic object, because of the risk of fistula or erosion of mucosal tissue trapped between two adherent foreign bodies. Rare earth metal magnets, or neodymium magnets, are very powerful small magnets that are sold in bulk and have caused multiple cases of bowel perforation necessitating surgical intervention. Ingestion of multiple magnets should lead to immediate endoscopic removal if technically feasible. If not, their migration through the GI tract should be followed radiographically until they are passed.

The use of balanced electrolyte lavage solutions containing polyethylene glycol may help the passage of small, smooth foreign bodies lodged in the intestine. Lavage is especially useful in hastening the passage of foreign bodies that may contain an absorbable toxic material such as a heavy metal. Failure of a small, smooth foreign body to exit the stomach after several days suggests the possibility of gastric outlet obstruction.

Most foreign bodies can be removed from the esophagus or stomach by a skilled endoscopist. In some circumstances an alternative technique can be used. An experienced radiologist using fluoroscopy can utilize a Foley catheter with balloon inflated below the foreign body to extract esophageal coins in the upper esophagus while the awake patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position. Contraindications include precarious airway, history that foreign body has been present for several days, and previous esophageal surgery.

Brumbaugh DE et al: Management of button battery-induced hemorrhage in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52(5): 585–589 [PMID: 215028305].

Hurtado CW, Furuta GT, Kramer RE: Etiology of esophageal food impactions in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;52(1):43–46 [PMID: 20975581].

Hussain SZ et al: Management of ingested magnets in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012 Sep;55(3):239–242 [PMID: 22785419].

Kay M, Wyllie R: Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2005 Jun;7(3):212–218 [PMID: 15913481].

Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolec M: Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics 2010; 125(6):1168–1177 [PMID: 20498173].

Waltzman ML: Management of esophageal coins. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006;18(5):571–574 [PMID: 16969175].

DISORDERS OF THE STOMACH & DUODENUM

HIATAL HERNIA

In paraesophageal hiatal hernias, the esophagus and GE junction are in their normal anatomic position, but the gastric cardia is herniated through the diaphragmatic hiatus alongside the GE junction. In sliding hiatal hernias, the GE junction and a portion of the proximal stomach are displaced above the diaphragmatic hiatus. Sliding hiatal hernias are common. Congenital paraesophageal hernias are rare in childhood; patients may present with recurrent pulmonary infections, vomiting, anemia, failure to thrive, or dysphagia. The most common cause of paraesophageal hernia is previous fundoplication surgery. Radiographic studies typically reveal a cystic mass in the posterior mediastinum or a dilated esophagus. The diagnosis is typically made with an upper GI series or a CT scan of the chest and abdomen. Presence of a Schatzki ring on upper GI has been found to be associated with hiatal hernia in 96% of children and should increase the index of suspicion. Recently, use of pH Impedance probe testing has been proposed as an effective method to identify hiatal hernia in children, where inversion of the usual acid:nonacid reflux ratio to more than 1.0 was reported to have a sensitivity of 93.8% and specificity of 79.6%. Treatment in symptomatic cases is generally surgical, with laparoscopic approach being used more commonly. Controversy exists about using biosynthetic mesh in the repair of these hernias, as its use definitely decreases the risk of recurrent hernia but has also been associated with esophageal erosion in children. GE reflux may accompany sliding hiatal hernias, although most produce no symptoms. Fundoplication is indicated if paraesophageal or sliding hiatal hernias produce persistent symptoms, though the presence of a preoperative hiatal hernia has been found to triple the risk of recurrent GERD following fundoplication.

Towbin AJ, Diniz LO: Schatzki ring in pediatric and young adult patients. Pediatr Radiol 2012 Dec;42(12):1437–1440 [PMID: 22886377].

Van Niekerk ML: Laparoscopic treatment of type III para-oesophageal hernia. S Afr J Surg 2011 Feb;49(1):47–48 [PMID: 21933485].

Wu JF et al: Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH: the diagnosis of sliding hiatal hernia in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol 2013 Nov;48(11):1242-8 [PMID: 23397115].

PYLORIC STENOSIS

The cause of postnatal pyloric muscular hypertrophy with gastric outlet obstruction is unknown. The incidence is 1–8 per 1000 births, with a 4:1 male predominance. A positive family history is present in 13% of patients. Recent studies suggest that erythromycin in the neonatal period is associated with a higher incidence of pyloric stenosis in infants younger than 30 days, though the mean age at diagnosis in a large population-based study was 43.1 days. Epidemiological studies identify no increased risk of pyloric stenosis with macrolide antibiotic exposure via breast milk.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Projectile postprandial vomiting usually begins between 2 and 4 weeks of age but may start as late as 12 weeks. Vomiting starts at birth in about 10% of cases and onset of symptoms may be delayed in preterm infants. Vomitus is rarely bilious but may be blood-streaked. Infants are usually hungry and nurse avidly. Constipation, weight loss, fretfulness, dehydration, and finally apathy occur. The upper abdomen may be distended after feeding, and prominent gastric peristaltic waves from left to right may be seen. An oval mass, 5–15 mm in longest dimension can be felt on deep palpation in the right upper abdomen, especially after vomiting. This palpable “olive,” however, was only present in 13.6% of patients studied.

B. Laboratory Findings

Hypochloremic alkalosis with potassium depletion is the classic metabolic findings, though low chloride may be seen in as few as 23% and alkalosis in 14.4%. These findings may not be as common in younger infants and their absence should not dissuade from the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical setting. Dehydration causes elevated hemoglobin and hematocrit. Mild unconjugated bilirubinemia occurs in 2%–5% of cases.

C. Imaging

Ultrasonography shows a hypoechoic muscle ring greater than 4-mm thick with a hyperdense center and a pyloric channel length greater than 15 mm. A barium upper GI series reveals retention of contrast in the stomach and a long narrow pyloric channel with a double track of barium. The hypertrophied muscle mass produces typical semilunar filling defects in the antrum. Isolated pylorospasm is common in young infants and by itself is insufficient to make a diagnosis of pyloric stenosis. Infants presenting younger than 21 days may not fulfill these classic ultrasonographic criteria and may require clinical judgment to interpret “borderline” measures of pyloric muscle thickness.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Ramstedt pyloromyotomy is the treatment of choice and consists of incision down to the mucosa along the pyloric length. The procedure can be performed laparoscopically, with similar efficacy and improved cosmetic results compared to open procedures. An alternative, double Y, form of pyloromyotomy may promote more rapid resolution of vomiting and increased weight gain in the first postoperative week compared to the traditional Ramstedt procedure. Treatment of dehydration and electrolyte imbalance is mandatory before surgical treatment, even if it takes 24–48 hours. Use of IV cimetidine and other acid-blocking agents has been shown in small studies to rapidly correct metabolic alkalosis, allowing more rapid progression to surgery and resolution of symptoms. Patients often vomit postoperatively as a consequence of gastritis, esophagitis, or associated GE reflux. The outlook after surgery is excellent, though patients may show as much as a four times greater risk for development of chronic abdominal pain of childhood The postoperative barium radiograph remains abnormal for many months despite relief of symptoms.

Leong MM et al: Epidemiological features of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Taiwanese children: a Nation-Wide Analysis of Cases during 1997–2007. PLoS One 2011;6(5):e19404 [PMID: 21559291].

Lin KJ, Mitchell AA, Yau WP, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S: Safety of macrolides during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013 Mar;208(3):221.e1–e8 [PMID: 232542493].

Tutay GJ, Capraro G, Spirko B, Garb J, Smithline H: Electrolyte profile of pediatric patients with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013 Mar 22;29(4):465–468 [PMID: 23528507].

GASTRIC & DUODENAL ULCER

General Considerations

General Considerations

Gastric and duodenal ulcers occur at any age. Boys are affected more frequently than girls. In the United States, most childhood gastric and duodenal ulcers are associated with underlying illness, toxins, or drugs that cause breakdown in mucosal defenses.

Worldwide, the most common cause of gastric and duodenal ulcer is mucosal infection with the bacterium H pylori. Between 10% and 20% of North American children have antibodies against H pylori. Antibody prevalence increases with age, poor sanitation, crowded living conditions, and family exposure. In some developing countries, over 90% of schoolchildren have serologic evidence of past or present infection. Infection is thought to be acquired in childhood, but only in a small percentage of infected persons will infection lead to nodular gastritis, peptic ulcer, or in the case of long-standing infection, gastric lymphoid tumors, and adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Some bacterial virulence factors have been identified, but the host and bacterial characteristics that contribute to disease progression are still largely unknown. In contrast to ulcers secondary to H pylori, non–H pylori ulcers tend to occur as frequently in girls as boys, present at a younger age, and are more likely to recur. In a large study of over 1000 children undergoing endoscopy, 5.4% had ulcers, with 47% of these due to H pylori, 16.5% related to NSAIDs, and 35.8% unrelated to either HP or NASIDs. Recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of non–H pylori peptic ulcers is increasing.

Illnesses predisposing to secondary ulcers include central nervous system (CNS) disease, burns, sepsis, multiorgan system failure, chronic lung disease, Crohn disease (CrD), cirrhosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. The most common drugs causing secondary ulcers are aspirin, alcohol, and NSAIDs. NSAID use may lead to ulcers throughout the upper GI tract but most often in the stomach and duodenum. Severe ulcerative lesions in full-term neonates have been found to be associated with maternal antacid use in the last month of pregnancy.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

In children younger than 6 years, vomiting and upper GI bleeding are the most common symptoms of gastric and duodenal ulcer. Older children are more likely to complain of epigastric abdominal pain. The first attack of acute H pylori gastritis may be accompanied by vomiting and hematemesis. Ulcers in the pyloric channel may cause gastric outlet obstruction. Chronic blood loss may cause iron-deficiency anemia. Deep penetration of the ulcer may erode into a mucosal arteriole and cause acute hemorrhage. Penetrating duodenal ulcers (especially common during cancer chemotherapy, immunosuppression, and in the intensive care setting) may perforate the duodenal wall, resulting in peritonitis or abscess.

B. Diagnostic Studies

Upper GI endoscopy is the most accurate diagnostic examination. The typical endoscopic appearance of an ulcer is a white exudative base with erythematous margins (Figure 21–4). Endoscopy also provides the mechanism for testing of other causes of peptic symptoms such as esophagitis, eosinophilic GI disease, and celiac disease (CD). Endoscopic diagnosis of active H pylori infection may be achieved by histologic examination of gastric biopsies or measurement of urease activity on gastric tissue specimens. Additional noninvasive methods of diagnosis of active H pylori infection include evaluation of breath for radiolabeled carbon dioxide after administration of radiolabeled urea by mouth and detection of H pylori antigen in the stool. False-negative results for the latter two tests have been described when the patient is taking a PPI. Serum antibodies against H pylori have poor sensitivity and specificity, and do not prove that there is active infection or that treatment is needed. For severe or recurrent ulcerations not caused by H pylori, stress, or medications, a serum gastrin level may be considered to evaluate for a gastrin-secreting tumor (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), though mild to moderate elevation in gastrin levels can be seen with use of PPI drugs. Upper GI barium radiographs may show an ulcer crater. Radiologic signs suggestive of peptic disease in adults (duodenal spasticity and thick irregular folds) are not reliable indicators in children.

Figure 21–4. Gastric ulcer. White exudate coats the ulcer bed of antral ulcer that is surrounded by an erythematous margin.

Figure 21–4. Gastric ulcer. White exudate coats the ulcer bed of antral ulcer that is surrounded by an erythematous margin.

Treatment

Treatment

Acid suppression or neutralization is the mainstay of noninfectious ulcer therapy. Liquid antacids in the volumes needed to neutralize gastric acid are usually unacceptable to children. H2-receptor antagonists and PPIs are more effective and usually produce endoscopic healing in 4–8 weeks.

As an adjunct therapy, 7- to 14-day courses of sucralfate may be helpful as a mucosal protective agent to speed healing and decrease symptoms. Bland “ulcer diets” do not speed healing, but foods causing pain should be avoided. Caffeine should be avoided because it increases gastric acid secretion. Aspirin, alcohol, NSAIDs, and other gastric irritants should be avoided as well.

Treatment of symptomatic H pylori infection requires eradication of the organism, a goal that remains elusive in children. The optimal medical regimen is still undetermined. The most common regimen is a triple combination of amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and PPI. Quadruple combinations, involving an additional antibiotic, may yield higher eradication rates. Alternative antibiotics include metronidazole, imidazole, tetracycline, and levofloxacin. Bismuth subsalicylate is commonly used as a substitute for the PPI. Regimens are typically continued for a minimum of 10 days. Sequential therapy, which involves induction with amoxicillin plus PPI for 5 days followed by clarithromycin/metronidazole/PPI for 5 days, may also yield higher eradication rates than standard triple combination therapy. Resistance to antibiotics is common and varies by region of the world. Regional antibiotic resistance patterns for H pylori should be a guide in selecting a treatment regimen for symptomatic infection. Test of cure can be achieved by either the urease breath test or fecal H pylori antigen test.

Endoscopic therapy of bleeding ulcers may be considered for severe or refractory lesions posing a risk for significant morbidity or mortality. Therapeutic options include injection therapy, application of monopolar or bipolar electrocoagulation, placement of clipping devices, or use of argon plasma coagulation.

Homan M, Hojsak I, Kolaček S: Helicobacter pylori in pediatrics. Helicobacter 2012 Sep;17(Suppl 1):43–48 [PMID: 22958155].

Moya DA, Crissinger KD. Helicobacter pylori persistence in children: distinguishing inadequate treatment, resistant organisms, and reinfection. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012 Jun;14(3):236–242 [PMID: 22350943].

Tam YH et al: Helicobacter pylori-positive versus Helicobacter pylori-negative idiopathic peptic ulcers in children with their long-term outcomes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48(3):299–305 [PMID: 19274785].

CONGENITAL DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA

Herniation of abdominal contents through the diaphragm usually occurs through a posterolateral defect involving the left side of the diaphragm (foramen of Bochdalek). In about 5% of cases, the diaphragmatic defect is retrosternal (foramen of Morgagni). In eventration of the diaphragm, a subtype of CDH, a leaf of the diaphragm with hypoplastic muscular elements balloons into the chest and leads to similar but milder symptoms. Hernias result from failure of the embryologic diaphragmatic anlagen to fuse and divide the thoracic and abdominal cavities at 8–10 weeks’ gestation. The herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity can lead to pulmonary hypoplasia and significant cardiovascular dysfunction after birth, in particular severe persistent pulmonary hypertension.

Diagnosis of CDH is typically made prenatally by ultrasound. Associated congenital malformations, most commonly cardiovascular, are commonly seen. With the advent of improved care of cardiopulmonary disease in the newborn period, including the use of inhaled nitric oxide, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, survival has improved for infants with CDH and is as high as 70%–90% in some centers. Fetal surgery with tracheal occlusion has been attempted to improve fetal pulmonary development. Operative repair of the diaphragmatic defect is usually performed in the newborn period once cardiopulmonary stabilization is achieved, with increasing utilization of laparoscopic and thoracoscopic minimally invasive approaches. Occasionally, diaphragmatic hernia is first identified in an older infant or child during incidental radiograph or routine physical examination. These children usually have a much more favorable prognosis than neonates. CDH survivors are often found to have significant chronic pulmonary disease as well as GER, the latter possibly resulting from abnormal intrinsic innervation of the lower esophagus.

Mettauer NL et al: One-year survival in congenital diaphragmatic hernia, 1995–2006. Arch Dis Child 2009;94:407 [PMID: 19383869].

Tovar JA: Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012 Jan 3;7:1 [PMID: 22214468].

CONGENITAL DUODENAL OBSTRUCTION

General Considerations

General Considerations

Obstruction is generally classified into intrinsic and extrinsic causes, although rare cases of simultaneous intrinsic and extrinsic anomalies have been reported. Extrinsic duodenal obstruction is usually due to congenital peritoneal bands associated with intestinal malrotation, annular pancreas, or duodenal duplication. In rare cases, a preduodenal portal vein has been associated with extrinsic obstruction as well. Intrinsic obstruction is caused by stenosis, mucosal diaphragm (so-called wind sock deformity), or duodenal atresia. In atresia, the duodenal lumen may be obliterated by a membrane or completely interrupted with a fibrous cord between the two segments. Atresia is more often distal to the ampulla of Vater than proximal. In about two-thirds of patients with congenital duodenal obstruction, there are other associated anomalies.

Imaging Studies

Imaging Studies

Diagnosis of congenital duodenal obstructions is often made prenatally by ultrasound. Prenatal diagnosis predicts complete obstruction in 77% of cases and is associated with polyhydramnios, prematurity, and higher risk of maternal-fetal complications. Presence of a “double bubble” on ultrasound, in association with an echogenic band in the second portion of the duodenum was found to be 100% sensitive and specific for an annular pancreas. Postnatal abdominal plain radiographs show gaseous distention of the stomach and proximal duodenum (the “double-bubble” radiologic sign). With protracted vomiting, there is less air in the stomach and less abdominal distention. Absence of distal intestinal gas suggests atresia or severe extrinsic obstruction, whereas a pattern of intestinal air scattered over the lower abdomen may indicate partial duodenal obstruction. Barium enema may be helpful in determining the presence of malrotation or atresia in the lower GI tract, as well as evaluating for radiographic evidence of Hirschsprung disease, which may also present with abdominal distension and vomiting.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Duodenal Atresia

Maternal polyhydramnios is common and often leads to prenatal diagnosis by ultrasonography. Vomiting (usually bile-stained) and epigastric distention begin within a few hours of birth. Meconium may be passed normally. Duodenal atresia is often associated with other congenital anomalies (30%), including esophageal atresia, intestinal atresias, and cardiac and renal anomalies. Prematurity (25%–50%) and Down syndrome (20%–30%) are also associated with duodenal atresia.

B. Duodenal Stenosis

In this condition, duodenal obstruction is not complete. Onset of obvious obstructive symptoms may be delayed for weeks or years. Although the stenotic area is usually distal to the ampulla of Vater, the vomitus does not always contain bile. Duodenal stenosis or atresia is the most common GI tract malformation in children with Down syndrome, occurring in 3.9%.

C. Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas is a rotational defect in which normal fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic anlagen does not occur, and a ring of pancreatic tissue encircles the duodenum. The presenting symptom is duodenal obstruction. Down syndrome and congenital anomalies of the GI tract occur frequently. Polyhydramnios is common. Symptoms may develop late in childhood or even in adulthood if the obstruction is not complete in infancy. Treatment consists of duodenoduodenostomy or duodenojejunostomy without operative dissection or division of the pancreatic annulus. Pancreatic function is normal.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

In almost all settings, surgical intervention (either laparoscopic or open) is required for congenital duodenal obstructive lesions. Typically, duodenoduodenostomy is performed to bypass the area of stenosis or atresia. For duodenal stenoses, however, there have been isolated reports of successful endoscopic treatment with balloon dilation. Thorough surgical exploration is typically done to ensure that no lower GI tract anomalies are present. More recent reports document the safety and utility of a laparoscopic approach. The mortality rate is increased in infants with prematurity, Down syndrome, and associated congenital anomalies. Duodenal dilation and hypomotility from antenatal obstruction may cause duodenal dysmotility with obstructive symptoms even after surgical treatment. Placement of transanastomotic feeding tubes at the time of the initial repair has been found to result in more rapid progression to full enteral feeds and decreased need for parenteral nutrition (PN). The overall prognosis for these patients is good, with the majority of their mortality risk due to associated anomalies other than duodenal obstruction.

Best KE et al: Epidemiology of small intestinal atresia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012 Sep;97(5):F353–F358 [PMID: 22933095].

Burgmeier C, Schier F: The role of laparoscopy in the treatment of duodenal obstruction in term and preterm infants. Pediatr Surg Int 2012 Oct;28(10):997–1000. Epub 2012 Aug 4 [PMID: 22991205].

Calisti A et al: Prenatal diagnosis of duodenal obstruction selects cases with a higher risk of maternal-foetal complications and demands in utero transfer to a tertiary centre. Fetal Diagn Ther 2008;24:478–482 [PMID: 19047796].

Freeman SB et al: Congenital gastrointestinal defects in Down syndrome: a report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Clin Genet 2009;75:180–184 [PMID: 19021635].

Mustafawi AR, Hassan ME: Congenital duodenal obstruction in children: a decade’s experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2008;18; 93–97 [PMID: 18437652].

DISORDERS OF THE SMALL INTESTINE

INTESTINAL ATRESIA & STENOSIS

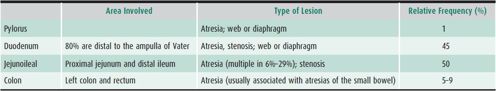

Excluding anal anomalies, intestinal atresia or stenosis accounts for one-third of all cases of neonatal intestinal obstruction (see Chapter 1). Antenatal ultrasound can identify intestinal atresia in utero; polyhydramnios occurs in most affected pregnancies. Sensitivity of antenatal ultrasound is greater in more proximal atresias. Other congenital anomalies may be present in up to 54% of cases and 52% are delivered preterm. In apparently isolated atresia cases, occult congenital cardiac anomalies have been reported in as many as 30%. In one large population-based study, the prevalence was 2.9 per 10,000 births, although there is some evidence that the prevalence may be increasing. The localization and relative incidence of atresias and stenoses are listed in Table 21–1. Although jejunal and ileal atresias are often grouped together, there are data to suggest that jejunal atresias are associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared to ileal atresia. These differences may be related to increased compliance of the jejunal wall, resulting in more proximal dilation and subsequent loss in peristaltic activity.

Table 21–1.Localization and relative frequency of congenital gastrointestinal atresias and stenoses.

Bile-stained vomiting and abdominal distention begin in the first 48 hours of life. Multiple sites in the intestine may be affected and the overall length of the small intestine may be significantly shortened. Radiographic features include dilated loops of small bowel and absence of colonic gas. Barium enema reveals narrow-caliber microcolon because of lack of intestinal flow distal to the atresia. In over 10% of patients with intestinal atresia, the mesentery is absent, and the SMA cannot be identified beyond the origin of the right colic and ileocolic arteries. The ileum coils around one of these two arteries, giving rise to the so-called Christmas tree deformity on contrast radiographs. The tenuous blood supply often compromises surgical anastomoses. The differential diagnosis of intestinal atresia includes Hirschsprung disease, paralytic ileus secondary to sepsis, midgut volvulus, and meconium ileus. Surgery is mandatory. Postoperative complications include short bowel syndrome (SBS) in 15% and small bowel hypomotility secondary to antenatal obstruction. Overall mortality has been reported at 8%, with increased risk in low-birth-weight and premature infants.

Best KE et al: Epidemiology of small intestinal atresia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012 Sep;97(5):F353–F358 [PMID: 22933095].

Burjonrappa S, Crete E, Bouchard S: Comparative outcomes in intestinal atresia: a clinical outcome and pathophysiology analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 2011;27(4):437–442 [PMID: 20820789].

Olgun H, Karacan M, Caner I, Oral A, Ceviz N: Congenital cardiac malformations in neonates with apparently isolated gastrointestinal malformations. Pediatr Int 2009;51:260–262 [PMID: 19405929].

Stollman TH et al: Decreased mortality but increased morbidity in neonates with jejunoileal atresia: a study of 114 cases over a 34-year period. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:217–221 [PMID: 19159746].

Walker K et al: A population-based study of the outcome after small bowel atresia/stenosis in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 1992–2003. J Pediatr Surg 2008;43:484–488 [PMID: 18358286].

INTESTINAL MALROTATION

General Considerations

General Considerations

The midgut extends from the duodenojejunal junction to the mid-transverse colon. It is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), which runs in the root of the mesentery. During gestation, the midgut elongates into the umbilical sac, returning to an intra-abdominal position during the 10th week of gestation. The root of the mesentery rotates in a counterclockwise direction during retraction causing the colon to cross the abdominal cavity ventrally. The cecum moves from the left to the right lower quadrant, and the duodenum crosses dorsally becoming partly retroperitoneal. When rotation is incomplete, the dorsal fixation of the mesentery is defective and shortened, so that the bowel from the ligament of Treitz to the mid-transverse colon may rotate around its narrow mesenteric root and occlude the SMA (volvulus). From autopsy studies it is estimated that up to 1% of the general population may have intestinal malrotation, which is diagnosed in the first year of life in 70%–90% of patients.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs

Malrotation with volvulus accounts for 10% of neonatal intestinal obstructions. Most infants present in the first 3 weeks of life with bile-stained vomiting or with overt small bowel obstruction. Intrauterine volvulus may cause intestinal obstruction or perforation at birth. The neonate may present with ascites or meconium peritonitis. Later presenting signs include intermittent intestinal obstruction, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy, or diarrhea. Associated congenital anomalies, especially cardiac, occur in over 25% of symptomatic patients. Many of these may be found in a subgroup of malrotation patients with heterotaxy syndromes, with associated asplenia or polysplenia. Older children and adults with undiagnosed malrotation typically present with chronic GI symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, bloating, and early satiety.

B. Imaging

An upper GI series is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, with a reported sensitivity of 96%, and classically shows the duodenojejunal junction and the jejunum on the right side of the spine. The diagnosis of malrotation can be further confirmed by barium enema, which may demonstrate a mobile cecum located in the midline, right upper quadrant, or left abdomen. Plain films of the abdomen in the newborn period may show a “double-bubble” sign, resulting in a misdiagnosis of duodenal atresia. CT scan and ultrasound of the abdomen may be used to make the diagnosis as well and are characterized by the “whirlpool sign” denoting midgut volvulus. Reversal of the normal position of the SMA and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) may be seen in malrotation, though normal position may be found in up to 29% of patients. Identification of the third portion of the duodenum within the retroperitoneum makes malrotation very unlikely.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Surgical treatment of malrotation is the Ladd procedure. In young infants the Ladd procedure should be performed even if volvulus has not occurred. The duodenum is mobilized, the short mesenteric root is extended, and the bowel is then fixed in a more normal distribution. Treatment of malrotation discovered in children older than 12 months is uncertain. Because volvulus can occur at any age, surgical repair is usually recommended, even in asymptomatic children. Laparoscopic repair of malrotation is possible but is technically difficult and is never performed in the presence of volvulus.

Midgut volvulus is a surgical emergency. Bowel necrosis results from occlusion of the SMA. When necrosis is extensive, it is recommended that a first operation include only reduction of the volvulus with lysis of mesenteric bands. Resection of necrotic bowel should be delayed if possible until a second-look operation 24–48 hours later can be undertaken in the hope that more bowel can be salvaged. The prognosis is guarded if perforation, peritonitis, or extensive intestinal necrosis is present. Mid-gut volvulus is one of the most common indications for small bowel transplant in children, responsible for 10% of cases in a recent series.

Lampl B, Levin TL, Berdon WE, Cowles RA: Malrotation and midgut volvulus: a historical review and current controversies in diagnosis and management. Pediatr Radiol 2009;39:359–366 [PMID: 19241073].

Nagdeve NG, Qureshi AM, Bhingare PD, Shinde SK: Malrotation beyond infancy. J Pediatr Surg 2012 Nov;47(11):2026–2032 [PMID: 23163993].

Sizemore AW, Rabbani KZ, Ladd A, Applegate KE: Diagnostic performance of the upper gastrointestinal series in the evaluation of children with clinically suspected malrotation. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38:518–528 [PMID: 18265969].

Taylor GA: CT appearance of the duodenum and mesenteric vessels in children with normal and abnormal bowel rotation. Pediatr Radiol 2011 Nov;41(11):1378–1383 [PMID: 21594544].

SHORT BOWEL SYNDROME

General Considerations

General Considerations

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is defined as a condition resulting from reduced intestinal absorptive surface that leads to alteration in intestinal function that compromises normal growth, fluid/electrolyte balance, or hydration status. The vast majority of pediatric patients with SBS have undergone neonatal surgical resection of intestine. The most common etiologies in children are necrotizing enterocolitis (45%); intestinal atresias (23%); gastroschisis (15%); volvulus (15%); and, less commonly, congenital short bowel, long-segment Hirschsprung disease, and ischemic bowel. In many instances, infants with SBS require PN in order to provide adequate caloric, fluid, and electrolyte delivery in the setting of insufficient intestinal absorptive function. The requirement of supplemental PN for more than 2–3 months in the setting of SBS or any other underlying disorder qualifies the diagnosis of intestinal failure (IF).

The goal in management of the patient with SBS is to promote growth and adaptation of the intestine such that adequate nutrition can be delivered and absorbed enterally. Many factors, including patient’s gestational age, postsurgical anatomic (including residual small bowel length and presence of ileocecal valve and/or colon), presence of small bowel bacterial overgrowth, and underlying surgical disease, influence the process and likelihood of bowel adaptation and achievement of enteral autonomy. Although no specific anatomic bowel length measurements offer 100% certainty in predicting clinical outcomes in SBS, residual small intestine less than 30 cm offers at least some prediction that a patient may require long-term, if not indefinite, PN. Serum citrulline level may serve as a reliable biomarker in order to help predict functional intestinal mass.

Symptoms & Signs

Symptoms & Signs

Typical symptoms for the patient with SBS are related to their underlying malabsorptive state, including diarrhea, dehydration, electrolyte or micronutrient deficiency states, and growth failure. Patients with SBS are also at risk for small bowel obstruction, bowel dilation and dysmotility (with secondary small bowel bacterial overgrowth), hepatobiliary disorders including cholelithiasis, nephrolithiasis due to calcium oxalate stones, oral feeding challenges, and GI mucosal inflammatory problems including noninfectious colitis and anastomotic ulcerations. For patients with IF, complications related to underlying PN therapy are common and can be life threatening. PN-associated liver disease (PNALD) is a progressive cholestatic liver injury that occurs in pediatric patients on PN and may progress to end-stage liver disease in 10% of affected patients. Recurrent catheter-related bloodstream infections are relatively common in pediatric patients with SBS and IF. Other complication-related central venous catheters including occlusions may require intervention.

Treatment & Prognosis

Treatment & Prognosis

Goal in management of SBS is to promote growth and adaptation while minimizing and/or treating complications of the underlying intestinal disorder or PN therapy. Intestinal rehabilitation for the child with SBS and IF refers to the multidisciplinary team approach to individual patient care, involving gastroenterology, nutrition, and surgery, and has been shown to improve outcomes. Enteral nutrition should be catered to favor absorption, commonly requiring continuous delivery of an elemental formula through a gastrostomy tube. Commonly prescribed pharmacologic adjuncts include acid suppressive therapy, antimotility and antidiarrheal agents, and antibiotics for the treatment of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Emerging therapies targeted to promote bowel adaptation include glucagon-like peptide 2 analogues, which show promise in potentially increasing absorption and bowel adaptation in early trials.

Management for the patient with SBS and IF should include strategies to manage or prevent complications related to PN therapy, including infection and liver disease. Antimicrobial lock solutions using either ethanol or antibiotics may have a role in reducing rate of infection. Compelling evidence over the past several years suggests that modification of parenteral lipid solution, either through reduction in dose of soy-based intralipid or replacement with a fish-oil based lipid solution (Omegaven), improves outcomes associated with PNALD in pediatric patients.

Autologous bowel reconstructive surgery (bowel lengthening) should be considered in a patient who is failing to advance enterally and has anatomy amendable to surgical intervention, typically with regards to adequate bowel dilation. Both the serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) procedure and longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (Bianchi) procedure have been successful in allowing weaning from TPN in up to 50% of patients in reported series. In recent years, the STEP procedure has gained favor as being potentially less technically demanding and repeatable, if the bowel dilates sufficiently after the initial procedure.

When medical, nutritional, and surgical managements fail, intestinal transplantation may be considered for a child with refractory and life-threatening complications of IF. Current outcome data after pediatric intestinal transplantation suggest 1- and 3-year survival rates of 83% and 60%, respectively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree