KEY POINTS

• Most pregnant women have gastrointestinal (GI) complaints during pregnancy.

• The majority of pregnant women experience nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

• Many pregnant women experience symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux.

• Others have more serious GI problems.

• Health care providers must become familiar with treatment options for the minor complaints and be able to diagnose patients with serious pathologic conditions in order to optimize maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Nausea and Vomiting

Background

Most patients complain of mild to severe nausea and vomiting during the first and early second trimesters of pregnancy. Although the etiology remains unclear, rapidly rising human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estrogen levels have been implicated.

Epidemiology

As many as 85% of pregnancies are accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The majority of these cases are self-limited and resolve spontaneously.

Evaluation

Physical assessment should include a complete abdominal examination.

Laboratory Tests

• Urinalysis will check for degree of dehydration (ketones, elevated specific gravity) and signs of a urinary tract infection (nitrite, leukocyte esterase).

• A chemistry panel is needed to detect and correct any electrolyte imbalances. The potassium concentration is especially important to note.

• Thyroid function tests (Free T3, Free T4, and TSH), while typically abnormal when there is nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, may be considered if a patient exhibits signs or symptoms of thyroid disease.

• Liver function tests along with amylase and lipase may also be abnormally elevated with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. A hepatitis panel can be considered in refractory cases or with markedly elevated transaminases in order to rule out some infectious etiologies.

• Human chorionic gonadotropin is ordered to screen for possible molar pregnancy.

• Ultrasound is ordered to determine whether a molar or partial molar pregnancy exists and to assess for presence of multifetal gestation.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Numerous illnesses present with nausea and vomiting (see Table 16-1).

Table 16-1 Differential Diagnosis for Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy

Clinical Manifestations

In severe or refractory cases, it is extremely important to rule out possible pathologic processes.

Treatment

Diet

Encourage patients to eat frequent, small meals that are rich in simple carbohydrates (e.g., dry toast, crackers).

Medications

Results from the Cochrane database (1) concluded that most drugs used for treating nausea and vomiting during pregnancy are more effective than is placebo.

• Bendectin contains both vitamin B6 (FDA class A) and doxylamine (FDA class A). Although it is not available in the United States due to medical–legal concerns, evidence indicates that both drug components appear safe and effective.

• Promethazine (Phenergan, FDA class C) and prochlorperazine (Compazine, FDA class C): Oral or rectal use has become very popular in the United States. Initial treatment favors rectal suppositories due to limited gastric absorption caused by emesis (2).

• Droperidol (Inapsine, FDA class C) represents a dopamine antagonist that is unresponsive to first-line therapy. Continuous infusion seems more effective in refractory cases (3).

• Meclizine (Antivert, FDA class B) and cyclinine (Marezine, FDA class B): These antihistamines are effective when given alone or in combination with vitamin B6 in 80% to 90% of patients.

• The promoting agent metoclopramide (Reglan, FDA class B) accelerates gastric emptying.

Alternative Therapies

• Ginger (FDA class C): Some evidence suggests that ginger decreases nausea. No adverse effects have been reported (4).

• Acupressure: Pressure stimulates the PC-6 site. Large studies have failed to confirm the efficacy of acupressure.

• Sensory afferent stimulation: Transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS) of P6 on the wrist has been effective (5).

Complications

• Electrolyte imbalance, especially hypokalemia, may induce cardiac arrhythmias.

• Hypovolemia (severe) may lead to uteroplacental insufficiency.

• Weight loss accompanied by negative nitrogen balance can result in ketone production.

HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Background

This manifests as severe nausea and vomiting with significant metabolic disturbances (6).

Etiology

Although the specific etiology is uncertain, hCG, estrogen, psychological factors, and certain personality traits are associated with hyperemesis gravidarum. Other suggested etiologies include thyrotoxicosis, serotonin anomalies, nutritional dysfunction, and Helicobacter pylori infections (7).

Epidemiology

The incidence of hyperemesis gravidarum is 1 in 200 pregnancies (0.5%). Women with a female fetus are more likely to have hyperemesis gravidarum, heavy ketonuria, and higher number of hospital admissions (8,9).

Evaluation

Laboratory

• Urinalysis: Specific gravity, urine ketones, and bilirubin evaluation. The specific gravity assesses hydration status of the patient, and bilirubin is used to evaluate for hepatitis and hemolysis.

• Serum electrolytes: Potassium and creatinine are especially pertinent.

• Hepatic functions: These tests evaluate for severe dehydration, and they are also elevated with hepatitis.

• Thyroid function tests in patients with signs or symptoms of hyperthyroidism may help rule out thyrotoxicosis (TSH is commonly suppressed in hyperemesis gravidarum).

• Fetal ultrasound: This is used to exclude molar or partial molar pregnancy and to assess for multifetal gestation.

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

• Please see Table 16-2.

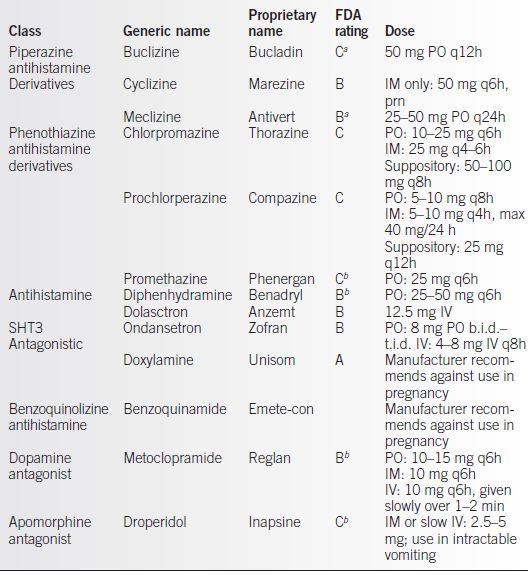

Table 16-2 Commonly Used Antiemetics in Pregnancy

aManufacturer recommends against use in early pregnancy. See Chapter 24 for details of FDA rating categories.

bManufacturer recommends use only if potential benefit justifies potential risk to fetus. FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Clinical Manifestations

Hyperemesis gravidarum usually manifests between 4 and 10 weeks of gestation and is resolved by 20 weeks of gestation. It is usually well tolerated at its inception but leads to weight loss, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, and ketosis.

Treatment

If hospitalization is required, patients should remain NPO for 24 to 48 hours and have intravenous replacement of isotonic fluids containing dextrose. Electrolytes can be replaced intravenously as clinically indicated. After 48 hours, their diet can be slowly advanced from clear liquids to abundant undersized meals rich in simple carbohydrates, such as dry toast and crackers.

Medications

Data from the Cochrane database (1) indicated that most drugs used for treating nausea and vomiting during pregnancy were more effective than placebo.

• Bendectin is a combination of vitamin B6 (FDA class A) and doxylamine (FDA class A). Although it is not available in the United States due to medical–legal concerns, evidence indicates that it is safe and effective.

• Promethazine (Phenergan, FDA class C) and prochlorperazine (Compazine, FDA class C) are used orally or rectally and are very popular in the United States. Rectal suppositories are recommended for initial treatment because of the lack of gastric absorption resulting from emesis.

• Droperidol (Inapsine, FDA class C) represents a dopamine antagonist that is unresponsive as first-line therapy. However, continuous infusion is effective for refractory cases.

• Theclizine (Antivert, FDA class B) and cyclinine (Marezine, FDA class B) are antihistamines that are effective alone or in combination with vitamin B6 in 80% to 90% of patients.

• Promoting agents: Metoclopramide (Reglan, FDA class B) accelerates gastric emptying.

• Alternative therapies

• Ginger (FDA class C): Some evidence suggests that ginger decreases nausea. Adverse associations have not been reported.

• Acupressure: This treatment stimulates the PC-6 site with pressure, but numerous studies have not confirmed its efficacy.

• Sensory afferent stimulation: TENS of P6 on the wrist has been effective (5).

• Ondansetron (Zofran, FDA class B): This agent is effective for refractory cases.

• Steroids: In some trials, limited courses of methylprednisolone have been effective.

• This therapy remains controversial (6).

• Glycopyrrolate (Robinul, FDA class B): This agent is acceptable for patients with ptyalism.

Additional Therapy for Refractory Cases

• Enteral feedings: This option should be considered for patients with significant weight loss and inability to keep down food for 1 to 2 weeks or longer. It enables normal function of the intestines.

• Hyperalimentation: This may be necessary in certain cases to help maintain volume requirements and allow weight gain. This treatment requires placement of a central venous line, which increases the risk of systemic infection and other serious complications. Due to associated risks in pregnancy, this option is generally reserved for cases in which enteral feedings have been unsuccessful.

• Vitamins: Intravenous thiamine and multivitamin should be considered in patients unable to tolerate oral intake for 1 to 2 weeks or longer.

Complications

• Mallory-Weiss tear of esophagus.

• Diaphragmatic tear (10).

• Vitamin deficiency, including Wernicke encephalopathy (vitamin B deficiency).

• Renal damage resulting from hypovolemia.

• Intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity, and fetal death have been associated with these disorders (8).

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Background

Definition

Reflux esophagitis or dyspepsia results in reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Relaxation of the esophageal sphincter due to elevated progesterone levels and increased intra-abdominal pressure from the expanding uterus are reasons that this condition complicates a large percentage of pregnancies.

Epidemiology

As many as 80% of Caucasian and 10% of African American women experience symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux at some point during pregnancy. The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is similar across all trimesters of pregnancy (11). There is a correlation with prepregnancy body mass index and GERD symptoms (12).

Evaluation

A history and physical should include careful examination of the chest and the abdomen. Symptoms include classical substernal or epigastric burning or pain that usually occurs after meals or when supine.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular pain (angina), pulmonary causes (pneumonia or pleuritic chest pain), and other etiologies of abdominal pain (cholecystitis, appendicitis, or other intra-abdominal processes). In the second and third trimesters, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome or hepatic hematoma must also be considered.

Treatment

Medications

• Oral antacids such as Maalox or Mylanta decrease gastric acid levels and may be effective in mild cases.

• Histamine-2 (H-2) receptor antagonist (FDA class B drugs).

• Cimetidine (Tagamet, FDA class B) has antiandrogenic activity, and it is recommended that other H-2 blockers be used initially.

• Ranitidine (Zantac, FDA class B). A dose of 150 mg twice a day appears to be effective.

• Famotidine (Pepcid, FDA class B). The dosage for GERD is 20 to 40 mg twice a day.

• Nizatidine (Axid, FDA class B). The usual dose is 150 mg b.i.d.

• Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (Omeprazole, FDA class C, Lansoprazole, FDA class B): These drugs control gastric secretions and are excreted in human milk. If used postpartum, breast-feeding should be avoided. Reserve the use of PPIs for cases refractory to H2 blockers because carcinogenic and adverse fetal effects have been reported in animal studies.

PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE (PUD)

Background

Definition

A peptic ulcer is an ulcerative area in the gastric lining. Evidence suggests that the incidence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is lower during pregnancy because of decreased gastric acid output and increased protective mucus production resulting from elevated progesterone levels. The incidence of PUD in pregnancy is quite low—this disorder complicates 1 in every 4000 pregnancies. The incidence may be actually higher because the diagnosis is difficult during pregnancy (13). Pregnancy is considered to be protective against PUD.

Pathophysiology

Excess acid production and the failure of mucus to protect the underlying mucosa are considered the primary causes. Risk factors include genetic predisposition, older age, smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or aspirin. H. pylori has been also implicated as a causative agent, and it is present in 85% to 100% of duodenal ulcers (14).

Evaluation

History and Physical

Patients usually have long-term GERD. Symptoms suggestive of gastric ulcers include dull, epigastric pain that radiates to the back. Pain improves with eating or antacids. Duodenal ulcers result in sharp or burning epigastric pain.

Tests

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree