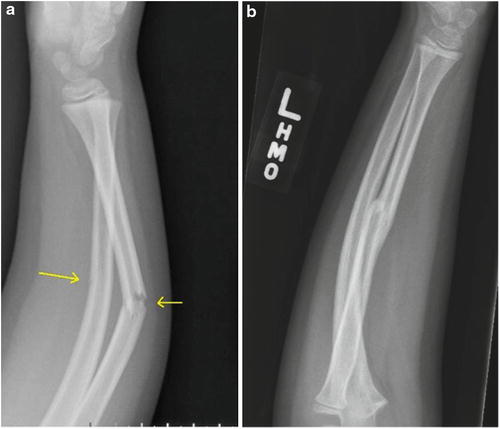

Fig. 1

Lateral radiograph of a Galeazzi fracture with apex volar angulation and volar dislocation of the DRUJ. The distal ulnar physis is intact (Photo courtesy of Kevin J. Little, MD)

Injuries Associated with Galeazzi Fractures

Galeazzi fractures in children are associated with distal ulnar physeal separations. These Salter-Harris I, II, or III injuries lead to a remarkably high rate of distal ulnar physeal arrest, as high as 50 %. Additionally, Galeazzi fractures have been associated with ipsilateral radial head dislocations or proximal radioulnar joint dislocations (Reckling 1982; Kontakis et al. 2008; Akalin et al. 2010). These injuries are described as Monteggia variants of Galeazzi fractures.

Classification of Galeazzi Fractures

Letts and Rowhani developed the classification for pediatric Galeazzi fractures (Letts and Rowhani 1993) which is described in Table 1. In Letts’ case series, the most common type of Galeazzi fracture was Type BII. This type of fracture is a distal third radius fracture with an epiphyseal fracture of distal ulna and dorsal displacement of ulnar metaphysis (Fig. 2).

Table 1

Galeazzi equivalent fractures in children

Letts and Rowhani classification of pediatric Galeazzi equivalent fractures | |

|---|---|

Type A: Fracture of the radius at the junction of the middle third with the distal third | I: Dorsal dislocation of the distal ulnar end |

II: Distal epiphysiolysis of the ulna with dorsal displacement of the metaphysis | |

Type B: Fracture of the radius at the distal third level | I: Dorsal dislocation of the distal ulnar end |

II: Distal epiphysiolysis of the ulna with dorsal displacement of the metaphysis | |

Type C: Greenstick fracture of the radius with dorsal bowing | I: Dorsal dislocation of the distal ulnar end |

II: Distal epiphysiolysis of the ulna with dorsal displacement of the metaphysis | |

Type D: Fracture of the radius with volar angulation | I: Volar dislocation of the distal ulnar end |

II: Distal epiphysiolysis of the ulna with volar displacement of the metaphysis | |

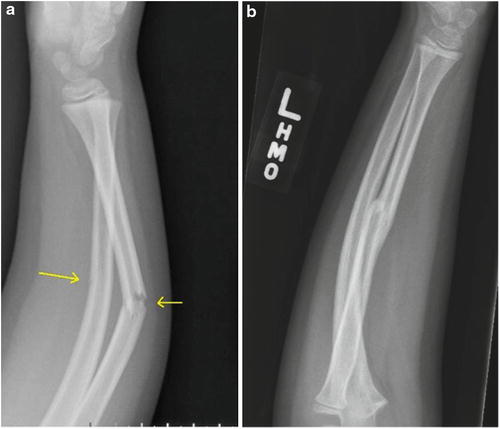

Fig. 2

Lateral radiograph of a Letts and Rowhani Type B II pediatric Galeazzi equivalent fracture with partial epiphyseal fracture (yellow arrow) (Photo courtesy of Kevin J. Little, MD)

Galeazzi Fracture Outcome Tools

In assessing the outcomes, no validated instrument has specifically been designed for these types of injury. Previous studies have classified Galeazzi fracture outcomes as excellent, fair, and poor. Table 2 shows the classification and the definition as described by Mikic in 1975 (Mikić 1975; Letts and Rowhani 1993). The authors do not use this outcome measure and prefer to base outcomes based on range of motion, pain, and functional use of the upper extremity.

Table 2

Mikic classification of outcomes following Galeazzi fractures

Outcome | Criteria |

|---|---|

Excellent | Radiographic union |

Anatomical alignment | |

Congruent DRUJ | |

Full wrist and elbow motion | |

Full forearm pronosupination | |

Fair | Patient satisfied with outcome but one or more of the following |

Delayed union | |

Minimum malalignment or shortening of the radius | |

Subluxation of the ulnar head | |

Excessive scar formation | |

Limitation of pronosupination of less than 45° | |

Poor | Patient dissatisfied with outcome plus one or more of the following |

Pain | |

Deformity of the forearm | |

Nonunion | |

Remarkable shortening or angulation of the radius | |

Limitation of pronosupination of more than 45° | |

Excessive restriction of elbow or wrist motion |

Galeazzi Fracture Treatment Options

Nonoperative

Indications/Contraindications

Unlike adults, where Galeazzi fractures have been termed the fracture of necessity (necessitating operative fixation), the majority of Galeazzi fractures in children can be successfully treated nonoperatively. However, the moniker of “fracture of necessity” still applies, in that, in order to treat this fracture nonoperatively, an anatomic reduction is necessary, as is weekly radiographic follow-up to ensure appropriate alignment is maintained. The indications and contraindications to nonoperative management are illustrated in Table 3. Though successful treatment with immobilization in both long- and short-arm casts has been reported, inferior results have been reported with short-arm compared to long-arm casting in a case series of pediatric Galeazzi fractures (Walsh et al. 1987). As children approach skeletal maturity, the chance for failure of nonoperative treatment approaches that of adults (up to 92 %) and operative treatment should be strongly considered in any patient with closed physes (Eberl et al. 2008).

Table 3

Indications for nonsurgical management

Pediatric Galeazzi fractures | |

|---|---|

Nonoperative management | |

Indications | Contraindications |

Closed fractures in skeletally immature patients | Open fractures |

Skeletally mature patients | |

Inability to reduce DRUJ (malreduced radius fracture, interposed extensor tendon, ulnar head buttonholed through capsule, infolded periosteum) | |

Loss of closed reduction | |

Malreduced unrecognized injury | |

Technique

The reduction maneuver for pediatric Galeazzi fractures is dependent on the characteristics of the injury, including the apex of the radius fracture and associated ulnar head dislocation. In the case of an apex volar radius fracture and an associated volar dislocation of the ulnar head, forearm pronation and volar forearm pressure often provide the reduction force necessary to allow for reduction of the radius angulation and a dorsal relocation of the ulnar head. Apex dorsal radius fracture angulation with an associated dorsal ulnar dislocation is reduced with supination of the forearm and dorsal forearm pressure. The arm is placed in a sugar-tong splint following reduction and overwrapped into a cast after the initial period of swelling subsides. Healing typically takes 4–6 weeks, and a protective splint is recommended for an additional 6–12 weeks due to increased refracture rates in distal shaft fractures (Fig. 3).

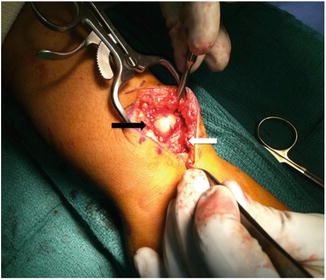

Fig. 3

(a) Lateral radiograph of a greenstick fracture of the radius with a dorsal DRUJ dislocation treated with closed reduction and casting with (b) radiographic union noted at 3 months and a clinically stable DRUJ with full ROM (Photo courtesy of Kevin J. Little, MD)

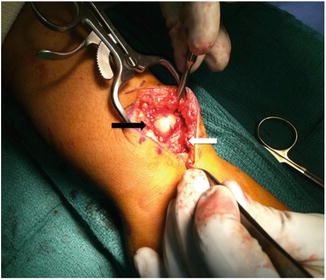

In the event that an anatomic closed reduction cannot be obtained or maintained, open reduction is required. Reduction of the DRUJ can be blocked by the extensor tendons, buttonholing of the ulnar head through the wrist capsule and extensor retinaculum, and interposed periosteum (Karlsson and Appelqvist 1987; Hanel and Scheid 1988; Castellanos et al. 1999; Landfried et al. 1991). Figure 4 illustrates the pediatric Galeazzi fracture variant involving a radius fracture coupled with a dorsal DRUJ dislocation, with a block to reduction by interposed extensor retinaculum (Landfried et al. 1991). Additionally, malreduction of the radius fracture can lead to an irreducible DRUJ.

Fig. 4

Clinical photograph of a patient with an irreducible dorsal DRUJ dislocation. Note the ulnar head (black arrow) subcutaneously with the extensor retinaculum (white arrow) blocking reduction (Photo courtesy of Kevin J. Little, MD)

Close radiographic follow-up is essential in these cases as loss of reduction can occur in up to 15 % of cases. The chance of a Galeazzi fracture requiring surgical treatment in a child increases as the patient nears skeletal maturity. Additionally, late presentation of an unrecognized Galeazzi fracture can prove challenging to treat nonoperatively, due to difficulty in obtaining an anatomic reduction of the radius and DRUJ, and operative stabilization may be necessary for these patients.

Outcomes

Outcome data for nonoperative treatment of Galeazzi fractures are limited, as there are few large series of these injuries. However, the overall outcomes for closed reduction and casting for these injuries are generally excellent or good with minimal sequelae (Eberl et al. 2008; Imatani et al. 1996). Even patients with Galeazzi fractures that are misdiagnosed initially and treated as simple radial shaft or distal radius fractures tend to regain full range of motion and suffer no long-term disability (Eberl et al. 2008). A minority of patients treated without surgery may lose some terminal motion (usually around 10°) at the wrist, most often terminal supination or wrist extension (Imatani et al. 1996; Letts and Rowhani 1993). Additionally, one series reported a 10 % rate of subjective occasional mild weakness and pain in nonoperatively treated patients (Eberl et al. 2008).

Operative Treatment for Galeazzi Fractures

Indications/Contraindications

Surgical treatment is indicated for a subset of pediatric Galeazzi fractures who fail initial closed reduction attempts. Open fracture/dislocations, injuries treated closed that experience loss of reduction or are unable to be anatomically reduced primarily, or those fractures in skeletally mature individuals are indications for operative intervention.

Surgical Procedure

The patient is placed under general anesthesia and placed on a regular operating table with a hand table attached (Table 4). Care is taken to position the patient as close to the hand table as possible to maximize the amount of the patient’s upper extremity located on the hand table. A non-sterile tourniquet is used. Prior to skin incision, the surgeon should attempt to reduce the fracture in the manner mentioned in the previous section. If anatomic reduction cannot be obtained, open reduction is necessary. The arm is exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage, and the pneumatic tourniquet is then inflated. The recommended tourniquet pressure in children is 50–100 mmHg above systolic pressure (Table 5).

Table 4

Operative procedure

Operative fixation of Galeazzi fractures | |

|---|---|

Preoperative planning | |

OR table | Regular OR bed |

Position | Supine with arm on hand table |

Fluoroscopy location | Mini-C arm coming in from the end of the hand table |

Equipment | Small fragment fixation set. Kirschner wires. Flexible nails |

Tourniquet | Unsterile tourniquet based on the patient’s arm circumference |

Table 5

Surgical checklist for operative treatment of Galeazzi fractures

Open reduction and internal fixation for Galeazzi fractures |

|---|

OR table: standard with arm table |

Position/positioning aids: supine with arm table without legs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|