CHAPTER 3 Fundamental Principles of Herbal Medicine

THE EVIDENCE BASE FOR BOTANICAL MEDICINE

Herbal medicine is undergoing rapid evolution as divergent streams of thought meet to redefine it in a modern clinical context. Many Western herbalists and naturopathic physicians share the concern that the mainstreaming of herbal medicine threatens to uproot it from its classical foundation; yet, practitioners are also concerned with having solid scientific validation that the products they recommend, or which their patients might already be using, meet basic standards of safety and efficacy. 1 2 3 4 Interestingly, patients are often more interested in anecdotal evidence of safety and risk in contrast to practitioners who are more likely to want detailed and objective evidence of benefit, safety, and risk.5 There is a tremendous need for a comprehensive way to evaluate herbal medicine efficacy and safety while integrating the concerns and experiences of all of the partners in health care: medical doctors and scientists, traditional practitioners, and those taking herbal medicines both for self-care and as patients.

This chapter proposes an integrative model of evidence-based herbal medicine that allows an intelligent synthesis of the various possible forms of data in the evaluation of botanical medicines, in order to include traditional evidence, scientific findings, and expert consensus based on clinical observation. This chapter also discusses the evidence upon which this text is based. In its broadest and most liberal interpretation, evidence-based medicine (EBM) can embody an ideal fusion of “clinical and laboratory research data with human experience,” as suggested by herbalist Simon Mills, rather than the reductionist, prepackaged mind-set that it has been accused of engendering.6 An integrative model of presenting evidence can be seen in the monograph collections of the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP), all of which acknowledge multiple levels of evidence including traditional use, clinical applications, and relevant science.

WHAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE?

The concept of EBM was first articulated in mid-nineteenth century Paris, and perhaps earlier.7 Described more recently as “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients,”7 EBM has been widely adopted in conventional medical circles as a hierarchic methodologic model of evaluating and ranking evidence for the determination of what is considered the best and most objective clinical practice. EBM as a packagable product-concept has become big business in medicine—a profitable host of commodities that include national conferences, hand-held computers that can be taken into patient consultations and programmed to generate EBM protocol for patients on the spot, books and journals, undergraduate and postgraduate training programs, and Web-based courses.7 Centers for the study of EBM have been established, as have extensive databases.7

Yet, responses to EBM as a medical paradigm based solely on external, objective evidence to the exclusion of the practitioner’s clinical judgment and experience have been highly equivocal, with widely varying criticisms ranging from “evidence-based medicine being old hat” to it being a “dangerous innovation, perpetrated by the arrogant to serve cost-cutters and suppress clinical freedom.” EBM has been “criticized for the inappropriateness of much evidence and its application to clinical practice, for logical inconsistencies, for potentially reducing the role of clinical judgment, for difficulties integrating into everyday professional practice, and for cultural bias.”8 EBM has been critically called “cookie-cutter” medicine, systematizing patient treatments according to specified protocol.9 Ironically, this appears to be a backward step in light of patients’ increasing demands for greater individual attention in medical care. Accusations of EBM being a cost-cutting measure are based upon the belief that streamlining diagnoses and treatments will represent cost savings to managed care organizations. 7 8 9

Practitioners naturally want to provide their patients with the best options. Many believe that relying solely on external, quantified evidence will relieve them of the burden of responsibility (or culpability) inherent in exercising individual clinical judgment. However, removing subjective observation and judgment entirely from clinical decision making requires objectifying and homogenizing patients. John Astin, PhD, writing in Academic Medicine, states

Decisions in medicine, irrespective of how much objective evidence we gather, always involves the weighing of probabilities.… To suggest that randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses and clinical practice guidelines will eliminate the need for clinical judgment is to misrepresent the realities of clinical medicine (both CAM and conventional). If medicine could be purely evidence-based (which is highly debatable both practically and financially), then in theory medical care…could essentially be administered by computers and computer algorithms.2

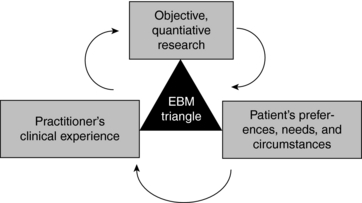

EBM proponents such as David Sackett suggest that the concept of EBM has been misinterpreted to be a one-dimensional orthodoxy based solely on objective, quantitative research methodologies, and that it is actually a much broader model than has been typically conveyed, with external evidence being only one of three important aspects of EBM.7 The other arms of EBM are the patient’s preferences, needs, and circumstances, and the practitioner’s clinical experience (Fig. 3-1).

Sackett’s description of EBM demonstrates its potential to serve as an integrative model:

The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centered clinical research.… Without clinical expertise, practice risks becoming tyrannized by evidence, for even excellent external evidence may be inapplicable to or inappropriate for an individual patient. Without current best evidence, practice risks becoming rapidly out of date, to the detriment of patients.… External clinical evidence can inform, but can never replace, individual clinical expertise, and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision.7

According to this, evidence-based medicine need not be restricted to reductionist forms such as RCTs and meta-analyses as some suggest (Box 3-1, Fig. 3-1). At its best, it is a “triangulation of knowledge from education, clinical practice, and the best research available for a given condition or therapy.”9

BOX 3-1 Research Methods for Beginners

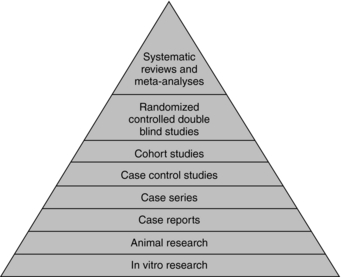

For those unfamiliar with research jargon, here is a brief overview of research methodologies and terminology. Research methods are categorized hierarchically in order of highest to lowest value of objectivity and reliability of the varying levels of evidence. The “evidence pyramid” is one such scheme for classifying research methods (Fig. 3-2).

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE FOR BOTANICALS DISCUSSED IN THIS TEXT

Scientific Evidence

Scientific data included in this book may fall into any of the following categories:

Problems with Conventional Research Methodologies for Botanical Therapies

Not all CAM therapies (i.e., prayer, homeopathy) are expected to stand up to classic methods of safety and efficacy testing. However, because herbs contain pharmacologically active substances, there is an implicit expectation that if herbs “really work” they should be able to measure up to the standards set for conventional drugs. Although this is theoretically sound, it is not reasonable in practice: Whole herbs are not the same as isolated drugs, nor are they applied as such by botanical medicine practitioners. A distinction can be made for single isolated active ingredients derived from botanicals, which are much more like pharmaceutical drugs than they are herbal products. RCTs for herbal products, in which all study group participants receive the same treatment are by definition given in a model antithetical to the way herbs are actually applied clinically by herbalists, wherein choice of herbs, formulation, and dosage are tailored specifically to the patient’s unique needs.6,9 There is also frequently a difference in the form of products used in clinical trials compared with those used by professional botanical medicine practitioners. Typically, botanical medicines are prescribed as multi-ingredient formulas, or as single herbs, in whole plant or whole plant extract forms that are most appropriate to the individual herb and specific patient. For most herbs, the biological activities of the constituents have not yet even been well characterized.10

Experience has shown that there are real benefits in the long-term use of whole medicinal plants and their extracts, since the constituents in them work in conjunction with each other. However, there is very little research on whole plants because the drug approval process does not accommodate undifferentiated mixtures of natural chemicals, the collective function of which is uncertain. To isolate each active ingredient from each herb would be immensely time-consuming at unsupportable cost, and is almost impossible in the case of preparations.11

Limits of Research and Research Biases

Implicit in relying upon the results of RCTs and other classic trials is the belief that they represent unbiased analyses. This may be a mistaken assumption. Even the RCT, the gold standard of research methodologies and one of the most reliable methodologies for limiting study biases, is not impervious to bias and is not without limitations.12 Methodologic features of RCTs, including trial quality, have been shown to influence effect sizes; and some researchers believe that eliminating the psychological component of clinical care from trials and minimizing placebo effect may cause studies to bear little resemblance to clinical practice.13,14

Politics also influences the choice of which studies get funded; what questions are asked; and whether, where, and how outcomes are published.15 Limited financial incentive on the part of pharmaceutical companies and researchers to investigate herbal products, particularly whole herbs, is due in part to the limited patentability of botanicals, and leads to fewer funding opportunities.16,17 Publication bias on the part of medical journals also has recently been raised as a significant concern. Additionally, there may be negative biases in the publication of case reports, with emphasis placed on the negative side effects of botanicals.3 John Astin, MD writing on CAM, states that the “approach of selectively citing one negative article while failing to cite any of the positive systematic reviews or meta-analyses is the antithesis of evidence-based medicine. It is, in short, opinion based medicine.”2 He states further that “The failure to cite such evidence contributes to a very misleading picture of the state of the scientific evidence base underlying CAM.”2

Nonetheless, in spite of the billions of dollars of herbal products sold in the United States alone, there are negligible reports of adverse herbal events compared with the volume of reported adverse drug events. In Europe, where millions of units of herbal products are sold and market surveillance and adverse events reporting systems are well established, there too are an amazingly small number of adverse reports.8 A major concern expressed about herbal medicine is the questionable safety of botanical medicines in pregnancy. Although indeed many are not to be used in pregnancy because of uncertainty about their safety, more than 90% of medications approved since 1980 have not been properly tested for mutagenicity or teratogenicity.18 Further, a growing body of evidence suggests that only 20% to 37% of conventional medical practices that are commonly accepted and used across a broad range of medical specialties are predicated on evidence from RCTs. Coronary bypass surgery was used for over 20 years before it was subjected to clinical trials.16,19,20 Although these statistics do not justify lack of evidence for nonconventional therapies, and do not negate the necessity for reliable clinical evidence, it does illustrate that there are sometimes double standards influencing attitudes about nonconventional therapies, and that there may at times be a suspension of common sense in pursuit of the holy grail of evidence (Box 3-2).

BOX 3-2 A Satirical View of EBM

Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Design: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Study selection: Studies showing the effects of using a parachute during free fall.

Main outcome measure: Death or major trauma, defined as an injury severity score >15.

Results: We were unable to identify any randomized controlled trials of parachute intervention.

Expert Consensus

Well into the early twentieth century, observational studies were considered an important source of medical evidence, declining in perceived value only over the past 20 years.12 Clinical decision making in medicine was based on observation, personal experience, and intuition.12 Even the randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) is only 50 years old and has been established as the definitive method of testing new drugs only since the 1980s.21

Although herbal medicine is frequently “dismissed by the orthodoxy as a fringe activity,”6 there are actually thousands of well-trained, highly knowledgeable and experienced clinical Western herbalists in numerous countries—England, Scotland, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States, to name a few. In Europe, particularly in Germany, phytotherapy is an accepted part of medical practice. Botanical experts are trained as either part of medical education if they are physicians, or in recognized botanical medicine educational programs with consistent curricula. In the United States, 13 states currently recognize naturopathic physicians who have graduated from accredited 4-year naturopathic colleges and passed their medical boards as legitimate physicians whose scope of practice includes botanical medicine. Over the past decade, a number of physicians have also gained significant experience in the clinical use of herbs. Although anecdotal evidence has largely been dismissed as invalid, the consensus of a large body of experts is entirely valid.

A large collective body of knowledge from contemporary clinical practitioners provides compelling evidence for the use of herbal medicines. Case studies (n = 1 studies), case series, uncontrolled trials, observational reports, and outcome-based studies all contribute important information to the dialogue on botanicals, ranging from establishing clinical effects that merit further study to providing clinical insights that corroborate traditional uses with modern pharmacologic effects.22,23 “Case study research provides a useful tool for investigation of unusual cases or therapies for which effectiveness data are lacking and for preliminary investigation of any factor that may influence patient outcome.” Qualitative research methods need to be developed further to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety of nonconventional therapies.21 Collaboration between conventionally trained researchers and traditional and medical herbalists to systematically document herbalists’ clinical use of botanical medicines is a rich and yet untapped area for botanical medicine research.

Traditional Evidence

Historical information referred to in this text is largely derived from classical botanical medicine texts, treatises and herbals, pharmacopoeias, monographs, and academic books on the history of botanical medicines. These appear in the references corresponding to individual chapters. Herbalist Kerry Bone best explains traditional use:

Traditional use occurs in the context of a traditional medicine system. This healing system may have evolved over thousands of years and be part of a great culture, or it may be part of a smaller or more primitive system. The important point is that traditional use is the refined knowledge of many generations, carefully evaluated and re-evaluated by many practitioners of the craft. It is not just the anecdotal accounts of a few practitioners.24

Bone defines folk use “as small-scale use; often in an isolated context.… Folk use should therefore not be confused with traditional use. That is not to say that folk use is without value. More that it should be placed in the context of the hypothetical rather than the definite.”24

REFERENCES USED IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THIS TEXT

The following were considered acceptable forms of references for inclusion in this text:

Boxes 3-3 and 3-4 give a complete list of botanical medicine texts, monographs, and databases consulted for this book.

BOX 3-3 Integrative Medicine Texts, Herbal Texts, and Herbal Monographs Referenced in the Book

Barrett M. Handbook of Clinically Tested Remedies, 1 and 2, 2004, Haworth Press, New York

Barton S. Clinical Evidence. London: BMJ Publishing Group, 2001.

Bruneton J. Pharmacognosy. Paris: Technique and Documentation, 1999.

Bruneton J. Toxic Plants Dangerous to Humans and Animals. Paris: Technique and Documentation, 1999.

Blumenthal M. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Austin: American Botanical Council, 2003.

Blumenthal M, Busse W, Goldberg A, et al. The Complete German Commission E Monographs Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin: American Botanical Council, 1998.

Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal Medicine: Expanded Commission E Monographs. Newton, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications, 2000.

Bone K. A Clinical Guide to Blending Liquid Herbs. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Bone K. Clinical Applications of Ayurvedic and Chinese Herbs. Queensland, AU: Phytotherapy Press, 2000.

European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). ESCOP Monographs: The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products, ed 2. New York: Thieme, 2003.

Evans WC. Trease and Evans’ Pharmacognosy. London: Saunders, 1998.

Felter HW, JU Lloyd. King’s American Dispensatory, vols 1 and 2, 1898, ed 18. Sandy Oregon: Eclectic Medical Publications, 1983.

Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press, 2003.

Kligler B, Lee R. Integrative Medicine: Principles for Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Kohatsu W. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Secrets. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

Kraft K, Hobbs C. Pocket Guide to Herbal Medicine. New York: Thieme, 2004.

LowDog T, Micozzi M. Women’s Health in Complementary and Integrative Medicine: A Clinical Guide. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2004.

McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, et al. American Herbal Products Association Botanical Safety Handbook. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1997.

McKenna DJ, Jones K, Hughes K, et al. Botanical Medicines: The Desk Reference for Major Herbal Supplements. New York: Haworth Press, 2002.

Mills S, Bone K. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Moerman D. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press, 2000.

O’Dowd MJ. The History of Medications for Women: Materia medica woman. New York: Parthenon Publishing Group, 2001.

Rakel D. Integrative Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003.

Rotblatt M, Ziment I. Evidence-Based Herbal Medicine. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

Upton R. American Herbal Pharmacopoeis and Therapeutic Compendium Series. Santa Cruz, CA: American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, 2004.

Weiss R, Fintelmann V. Herbal Medicine, ed 2. New York: Thieme, 2000.

Wichtl M. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals: A Handbook for Practice on a Scientific Basis. Stuttgart: Medpharm, 2004.

BOX 3-4 Internet Databases Consulted in This Text

No Author, n.d. http://www.cabi.org/

No Author, n.d. http://www.cinahl.com/

No Author, n.d. http://www.herbmed.org

No Author, n.d. http://www.mcphs.edu/

No Author, n.d. http://www.mdconsult.com/

No Author, n.d. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

No Author, n.d. http://www.naturalstandard.com/

No Author, n.d. http://www.ovid.com/

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree