Foreign Bodies and Caustic Ingestions

Marsha Kay

Robert Wyllie

FOREIGN BODIES

In the first recorded case of an ingestion of a foreign body, Frederick Wilheim, later known as Frederick the Great, swallowed a shoe buckle at the age of 5 years, which apparently passed without incident. In 1937, Jackson and Jackson reported 3266 esophageal and airway foreign body ingestions. These authors coined the phrase, “Advancing points perforate and trailing points do not,” subsequently referred to as Jackson‘s axiom. In addition, their writings formed the basis of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission small parts regulation, which bans toys and other articles intended for use by children ≤ age 3 that represent a hazard for choking, swallowing, and inhaling based on size criteria (≤2.25 × 1.25 in. [≤5.7 × 3.2 cm]). In 1966, Bigler reported extracting an esophageal foreign body with the use of a Foley catheter, and in 1972, Morissey reported the first case in which a foreign body was extracted endoscopically. By 1978, three reports of the endoscopic removal of foreign bodies in a total of 16 patients had been published, by Ament, van Thiel, and Bendig. Starting in the 1980s, a number of large series of endoscopic or radiologic retrieval of foreign bodies were reported.

Epidemiology

The type and incidence of foreign bodies ingested and reported vary by geographic region and the specialty of the authors. One of the largest reports published in the last two decades was by Nandi and Ong, who reported 2934 foreign body ingestions in China in the British Journal of Medicine. Eighty-four percent of the foreign bodies ingested in their series were fish bones, which were usually lodged in the esophagus. Three hundred and forty-three children were included in the series. Ingestions of fish bones were reported in 146 of the children, but coin ingestion was the second most common type of ingestion in children, accounting for 134 cases in the same series. In the United States, coin ingestion is the most common type of foreign body ingested during childhood. The exact incidence of foreign body ingestion in the United States is unknown, but data from the American Association of Poison Control Centers suggests that in 2004 alone there were more than 109,000 cases of foreign body ingestion by children and adolescents. Data from Sweden’s National Health Service indicate an incidence of foreign body ingestion of 122/million population per year. Approximately 1500 deaths in patients of all ages are caused annually in the United States by foreign body ingestion.

Approximately 80% of cases of foreign body ingestion occur in children, predominantly between the ages of 6 and 36 months, with coins being the objects most often ingested. In adults, the most common unintentional ingestions that become lodged are meat and fish bones. Intentional ingestions occur primarily in psychiatrically impaired individuals and prisoners. Individuals under the influence of alcohol may unintentionally swallow objects because their perception is impaired. Foreign body ingestions by gang members as part of initiation practices are becoming more frequent. A significant number of foreign body ingestions do not come to medical attention, and the objects pass without incident. It is estimated that 80% to 90% of foreign bodies ingested that come to medical attention pass spontaneously. For 10% to 20%, endoscopic removal is required, and surgery is ultimately required for 1% or fewer. Perforation of the intestinal tract, the most serious sequela of foreign body ingestion, occurs in less than 1% of cases. The higher rates reported in some series are primarily related to the subspecialty of the authors reporting the data. For example, the perforation rate would be anticipated to be higher in series reported by thoracic surgeons than in a series of all patients presenting to

an emergency room for evaluation. Sharp objects are associated with a higher perforation rate than dull objects. Approximately 75% of perforations occur at the appendix or near the ileocecal valve. Foreign body entrapment and subsequent perforation are also more likely to occur in the region of a congenital malformation, such as a Meckel diverticulum, or at a site of prior surgery.

an emergency room for evaluation. Sharp objects are associated with a higher perforation rate than dull objects. Approximately 75% of perforations occur at the appendix or near the ileocecal valve. Foreign body entrapment and subsequent perforation are also more likely to occur in the region of a congenital malformation, such as a Meckel diverticulum, or at a site of prior surgery.

The largest number of foreign bodies ingested by a single individual was 2533, reported by Chalk et al. in 1928. The woman, who had melancholia, was sent to a sewing room for therapy, where she ingested an assortment of pins, needles, and bobbins. Remarkably, the objects passed uneventfully, and the patient survived. In 1987, Henderson et al. reported a case of ingestion of 500 straight pins, which resulted in the patient’s death within 2 months as a consequence of multiple intestinal perforations. High number foreign body ingestions continue to be reported in the psychiatrically impaired, who may “save their treasure” by ingesting a variety of objects and who typically present with abdominal pain, distension, obstruction, and anemia, and require surgical removal of the foreign bodies, which may weigh several kilograms. One of the most remarkable reports of foreign body ingestion was by Yamamoto et al. in 1985, who reported the endoscopic removal of a chopstick from the duodenum of a 71-year-old man who had ingested the object 60 years earlier.

Esophageal Foreign Bodies

Clinical and Radiographic Features

Ninety percent of children have a history of ingestion or are observed to ingest an object. Approximately 90% of foreign bodies ingested in children are radiopaque. It is appropriate to obtain an x-ray film in every case of foreign body ingestion of an opaque object because objects may be lodged in the esophagus even in asymptomatic patients.

The most common site of foreign body obstruction in the gastrointestinal tract in children is the esophagus. Approximately 60% to 70% of foreign bodies that become entrapped in the esophagus are located in the proximal esophagus at the region of the cricopharyngeus. The second most common site is just above the lower esophageal sphincter, with approximately 20% of obstructions occurring in the mid-esophagus.

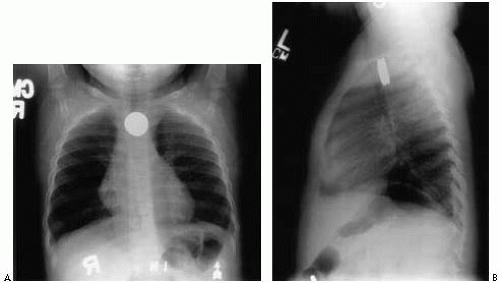

Coins are the foreign bodies most frequently ingested by children in the United States. The anteroposterior view on an x-ray film will demonstrate the coin en face, whereas the lateral view will show the edge of the coin (Fig. 7.1). This pattern is the opposite of the radiographic appearance of a coin lodged in the trachea. Coins lodged in the esophagus most frequently appear en face on the anteroposterior view, but the appearance of the lateral edge of a coin lodged in the esophagus on the anteroposterior view has also been reported.

Symptoms

The symptoms of foreign body obstruction vary according to the patient’s age and the nature of the foreign body. Symptoms in young children are nonspecific and can include choking, drooling, and poor feeding. Some children modify their diet to compensate for a partial obstruction —for example, consuming only liquids. Older children and teenagers report dysphagia and substernal chest pain. On occasion, the only symptoms of an esophageal foreign body are respiratory. These include wheezing, stridor, impaired speech, and recurrent infection. The foreign body may be noted incidentally on an x-ray film obtained to evaluate suspected pneumonia or reactive airway disease. The cause of the stridor is edema secondary to foreign body obstruction with subsequent impingement on the trachea. Rarely a patient with an esophageal foreign body may present with massive hematemesis as their initial presentation. This is caused by erosion of the foreign body into the aorta. Unfortunately, identification of the foreign body as the underlying cause of the hematemesis is usually at autopsy, as the hematemesis is typically life threatening, and these patients often can not be resuscitated.

Management

If patients are symptomatic (i.e., unable to swallow their secretions or experiencing respiratory difficulty), emergency endoscopy is indicated to remove the foreign body. Aspiration pneumonia is one of the potential complications of failure to remove a foreign body. In some centers, smooth foreign bodies may be removed by an experienced interventional radiologist with catheters. This procedure is potentially dangerous because the foreign body can “flip out” as the catheter is withdrawn and come to lie flat on the vocal cords, causing immediate respiratory compromise.

If patients are symptomatic (i.e., experiencing dysphagia or a “feeling that something is there”) but are able to handle their secretions, endoscopy can be deferred for 12 to 24 hours to allow for an appropriate period of preanesthetic fasting; an x-ray film should be obtained prior to endoscopy to verify that the foreign body is still in the esophagus. This management strategy is true for foreign bodies such as coins but does not apply to esophageal batteries, which are an exception and are discussed later in the chapter. Objects such as coins can pass spontaneously, especially coins located in the distal esophagus. Spontaneous passage may occur in up to one third of such cases. Glucagon has not been shown to be effective in pediatric patients in facilitating esophageal coin passage. On a cost per case basis, however, admission of the patient to the hospital for observation of an esophageal located coin with endoscopy reserved for coins that fail to pass within 16 hours has been shown to be less cost effective than earlier endoscopic removal.

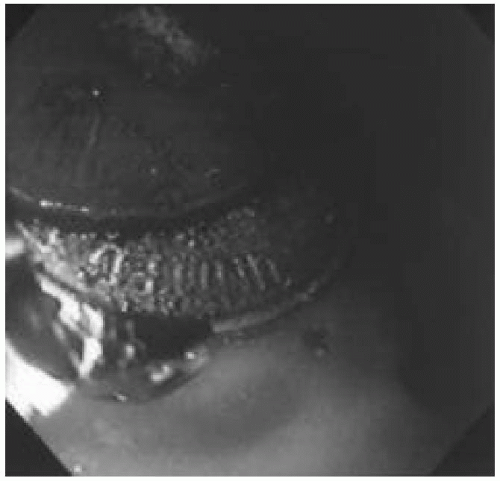

Gastric and Small Intestinal Foreign Bodies

Most foreign bodies that reach the stomach pass uneventfully through the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract within 4 to 6 days. Patients are instructed to consume a regular diet. The use of prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide is not indicated to increase the speed of passage. Parents should monitor the stools of their children to detect passage of the foreign body. Metal detectors have been used by a few for this purpose. If a patient is asymptomatic and the foreign body has not been noted in the stool, we generally recommend waiting for 3 weeks before obtaining an x-ray film to localize a known gastric foreign body. We generally wait an additional 3 weeks after obtaining the xray film if the patient remains asymptomatic, and obtain a second film 6 weeks after the ingestion. If the object is still in the stomach, we recommend endoscopic removal at that time. We have anecdotally noted that in cases of ingestion of multiple coins, gastric passage may be delayed as the coins appear to adhere to each other and endoscopic removal may be required (Fig. 7.2). No toxicity has been reported from retention of modern zinc containing “copper” pennies following the change in composition of the penny in 1982 to a zinc-predominant coin. Toxicity studies were carried out prior to the release of the various Euro coins with regard to the potential of zinc toxicity following ingestion. These coins have a lower zinc content than the American penny, and to date no cases of zinc intoxication following ingestion have been identified.

Figure 7.2 Endoscopic view of two coins in the stomach of a 4-year-old patient. The coins had been present for several weeks without passage. Alligator forceps are used to remove the coins. Note erosion of the penny from prolonged contact with gastric acid. (See color insert.) |

Potential problem sites downstream for foreign bodies include the pylorus, the fixed curves of the C loop of the duodenum, and the ileocecal valve. The duodenal C loop poses a problem because of its fixed retroperitoneal location. Objects that require endoscopic removal from the stomach and proximal small intestine can be placed into two categories, those that require removal because of their size and those that require removal because of their composition and physical characteristics.

Objects in the stomach of an adult patient that are longer than 10 cm cannot negotiate the duodenal C loop and therefore should be removed endoscopically at the time of identification. Successful negotiation of the duodenum by a toothbrush has never been reported. An ovoid object with a length of more than 5 cm or a thickness of more than 2 cm is unlikely to pass the pylorus in an adult and should be removed. Appropriate size modifications are required to make recommendations in younger patients. Patients with a congenital malformation, such as a duodenal web, an annular pancreas, or a surgical anastomosis may not be able to pass objects significantly smaller than the sizes indicated above. The size of an object may be magnified on x-ray films, and therefore some estimation is required, or measurement of a similar object can be used if the identity of the ingested object is known.

Management of Specific Ingested Foreign Bodies

Impacted Meat

Impacted meat is the most common foreign body causing obstruction in adolescents and adults. Up to 95% of adult patients who experience a meat impaction have underlying esophageal pathology, and the rate is also high in adolescents. Conditions that predispose patients to esophageal meat impaction include esophageal strictures or narrowing from a variety of etiologies including acid peptic disease, post-caustic ingestion, and postoperatively, esophageal motility disorders, and eosinophilic esophagitis. This condition, which is increasingly recognized in children and adults, results in a characteristic ringed esophageal appearance.

For patients who are symptomatic and unable to handle their secretions, immediate endoscopy is required to relieve the obstruction and prevent the potential complication of aspiration. Patients who are symptomatic but able to handle their secretions require endoscopy within 12 hours. Contrast radiography is contraindicated because of the potential for aspirating the contrast in addition to the impacted food. The use of meat tenderizers is also contraindicated because these agents have been associated with esophageal perforation and hypernatremia.

Batteries

The largest series of battery ingestions was reported by Litovitz et al. in 1992. This series, comprised of data from a national registry, reported 2382 ingestions in 2320 patients. Almost all the reported ingestions were button batteries. In that series, only 62 cylindric batteries were ingested. Hearing aids were the most common source of button batteries, representing more than 40% of the reported cases. In a third of these cases, the hearing aid was the child’s own. In this series, only 10% of the patients were symptomatic, and only two children sustained residual injury—in both cases esophageal strictures that required dilation. The battery transit time in the gastrointestinal tract was less than 24 hours in 23% of cases, less than 48 hours in 61% of cases, and less than 96 hours in 86% of cases. The transit time was longer than 1 week in only 4.5% of the cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree