Fever Without Source

Mark A. Ward

Martin I. Lorin

Mark W. Kline

Fever is one of the most common pediatric complaints. In the first few years of a child’s life, fever is second only to routine care as the reason for office or clinic visits. Between 5% and 20% of febrile children have no localizing signs on physical examination and nothing in the history to explain the fever. Fever without source (FWS), like febrile illness in general, is most commonly seen in children younger than age 5, with a peak prevalence between 6 and 24 months of age.

We define FWS as fever of relatively brief duration, arbitrarily 7 or fewer days, without an apparent source on history or physical examination. If the unexplained fever persists for longer than 7 days, it is commonly referred to as fever of undetermined origin (FUO). Although overlap exists between FWS and FUO, the differential diagnoses and the clinical approaches are different.

In most cases, FWS resolves spontaneously, without a specific diagnosis being established, and presumably is caused by a viral infection. In some cases, a relatively minor infectious process, either focal (e.g., otitis media, pharyngitis) or nonfocal (e.g., roseola), becomes apparent a few days into the febrile illness. Examples of infections with lengthy prodromal periods during which fever may be the only manifestation include roseola, cytomegalovirus infection, and typhoid fever. Because the duration of FWS, by definition, is brief and because so many children with self-limited viral infections present with FWS, the incidence of persistent infections or noninfectious chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g., juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) is much lower than that among children with FUO. Infrequently, FWS in an infant or child represents a drug reaction, an allergic or hypersensitivity disorder, or heat illness. A small number of young children presenting with FWS will manifest features of Kawasaki syndrome after a few days.

SERIOUS BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

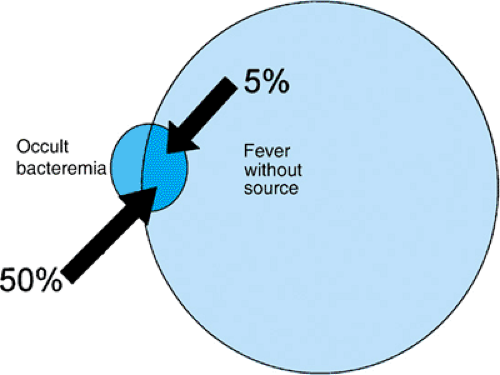

Except in the very young infant, most serious bacterial infections (SBIs) can be recognized by a careful history and physical examination. However, a small percentage of children with bacteremia cannot be identified by clinical examination alone. These children have occult bacteremia, which we define as the presence of a positive blood culture in a child who looks well enough to be treated as an outpatient and in whom the positive blood culture is not anticipated. Specifically, the child does not have any local infection that ordinarily would be associated with bacteremia (e.g., pneumonia or epiglottitis), although the child may have a minor infection, such as otitis media. Whereas less than 5% of children with FWS have occult bacteremia, more than 50% of children with occult bacteremia come from the pool of children with FWS (Fig. 132.1).

Occult bacteremia occurs with essentially the same frequency in lower, middle, and upper socioeconomic populations, and the prevalence varies more with the selection criteria for study than with the geographic or socioeconomic base of the study population. The highest frequency of occult bacteremia is in children younger than 2 years of age. For additional information about bacteremia in children, see Box 132.1.

Other SBIs of concern in children with FWS include meningitis and urinary tract infection (UTI). The former can occur in the absence of neurologic findings and without demonstrable neck stiffness or pain on flexion. Infants and young children with UTI may not have, or may not be able to express, abdominal pain, back pain, or pain on urination. Whereas bacterial enteritis also is considered a potential SBI in children with FWS, it is unlikely in the absence of diarrhea, although fever may precede the first loose stool by several hours.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Many of the diagnostic studies used to evaluate children with FWS are directed at excluding the presence of bacteremia or other SBIs. Failure to identify bacteremic children accurately subjects them to the potentially adverse sequelae of undiagnosed and untreated SBIs, including meningitis. Conversely, the indiscriminate use of diagnostic tests causes unnecessary expense and discomfort for the patient.

The advent of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, and more recently the conjugate pneumococcal vaccine, has markedly decreased the incidence of occult bacteremia and bacterial meningitis. The frequency of occult infection caused by Neisseria meningitidis and salmonellae has not changed. The decreased incidence of H. influenzae type b and pneumococcal infection in fully immunized children has led to a rethinking of the recommendations for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of children between 3 and 36 months of age with FWS. The current low risk of occult bacteremia or meningitis in these children no longer justifies routine blood culture, measurement of white blood cell (WBC) counts or other acute-phase reactants, or administration of antibiotics while awaiting results of blood culture in the nontoxic-appearing child who has received H. influenzae type b and pneumococcal vaccines. Because S. pneumoniae is associated more consistently with high fever and elevated WBC than are other organisms, these parameters will be less sensitive in children who have received the pneumococcal vaccine. The use of these vaccines will not impact the incidence of UTIs or bacterial enteritis.

BOX 132.1 Studies of Bacteremia in Children with Fever Without Source

Children with fever without source (FWS) are more likely to be bacteremic than are children with minor outpatient infections. In one series, blood cultures were obtained from all febrile children younger than 2 years of age presenting to the emergency department. The prevalence of bacteremia in children with infections such as otitis media and pharyngitis was 1.5%; in those with FWS, the prevalence was 3.9%. In another series, 3% of febrile children with evidence of upper respiratory tract infections had occult bacteremia, in contrast to those with FWS, for whom the prevalence was 9%. These series were published prior to the advent routine immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae, and the total prevalence would now be much lower but the ratios might well be similar. Although most patients with FWS (even those with high fevers) do not have bacteremia, higher fever tends to be associated with a greater risk of bacteremia, a trend especially pronounced with S. pneumoniae.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree