Female Sterilization

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide popularity of surgical sterilization has increased dramatically in the last few decades. In the United States alone, more than 1 million people undergo a sterilization operation each year. Data from the most recent U.S. National Survey of Family Growth indicate that by 1995, 39 percent of all women aged 15–44 years who were using some form of contraception had either been sterilized or reported that their partner had been sterilized (Piccinino and Mosher, 1998). This proportion was similar to that from a comparable survey in 1988, but more than double that reported in 1973 (Piccinino and Mosher, 1998).

TRENDS IN TUBAL STERILIZATION

Tubal sterilization was uncommon in the United States prior to 1970. The number of tubal sterilizations in U.S. hospitals increased dramatically, however, in the 1970s, from approximately 200,000 in 1970 to about 700,000 in 1977 (DeStefano and associates, 1982). The number of tubal sterilizations performed in hospitals began to decrease after 1977, with a corresponding increase in the number of tubal sterilizations performed in out-of-hospital facilities. By 1987, approximately one-third of all tubal sterilizations in the United States were performed on an outpatient basis (Schwartz and associates, 1989).

The rapid increase in popularity of outpatient tubal sterilization occurred concurrently with the increasing popularity of laparoscopy for tubal sterilization. The prevalence of tubal sterilization by laparoscopy increased from less than 1 percent in 1970 to approximately 33 percent by 1975 (Peterson and associates, 1981). This trend was accompanied by a decrease in length of hospital stay for tubal sterilization from 6.5 nights in 1970 to 4.0 nights in 1975–1978 (Layde and associates, 1981). Of the estimated 215,000 tubal sterilizations that required no overnight stay in 1987, 79 percent were performed by laparoscopy (Schwartz and associates, 1989).

TIMING OF STERILIZATION

Tubal sterilization can be performed concurrently with pregnancy termination (cesarean section, vaginal delivery, or induced abortion) or on an interval basis. The timing of sterilization may influence the surgical approach and method of tubal occlusion. For example, most procedures performed postvaginal delivery are minilaparotomy procedures with subumbilical incisions and partial salpingectomies. Interval procedures can be performed either by laparoscopy or minilaparotomy, although the former is more common. The timing of sterilization may also influence the choice of anesthesia. For example, sterilizations performed with caesarean sections require no separate anesthesia; some postpartum procedures are performed immediately following vaginal delivery using the same anesthesia, and others are performed during the same hospitalization using separate anesthesia. Interval sterilizations are usually performed by using either general or local anesthesia.

ANESTHESIA

POSTPARTUM STERILIZATION

Sterilization in the postpartum period can be performed using regional anesthesia, general anesthesia, or local anesthesia. When sterilization is performed immediately postpartum and epidural anesthesia has been used, a sterilization procedure can usually be performed with the same epidural anesthetic. Spinal anesthesia is often used for postpartum sterilization. When general anesthesia is used, care should be taken to avoid aspiration. Postpartum women are at increased risk for aspiration due to delayed gastric emptying.

INTERVAL STERILIZATION

Although interval sterilization is usually performed under general anesthesia, local anesthesia is a safe and appropriate alternative (Peterson, 1987; Bordahl, 1993; and their associates). Local anesthesia can be accomplished using lidocaine (0.5 percent) or bupivacaine (0.5 percent) with a 20-gauge spinal needle and injecting the anesthetic in a layer-by-layer fashion for periumbilical analgesia. Aspiration before injection will avoid intravascular instillation. After entry into the peritoneal cavity, lidocaine (1 percent) or bupivacaine (0.5 percent) can be dripped on each fallopian tube before tubal occlusion. Alternatively, local anesthetic can be injected into the mesosalpinx to reduce the pain of tubal manipulation (Thompson and associates, 1987). Spielman and associates (1983) have shown that 240 mg of lidocaine or 100 mg of bupivacaine provides sufficient analgesia for tubal sterilization at safe blood levels well below demonstrated toxicity.

SURGICAL APPROACH

Surgical approach to tubal sterilization is influenced by whether the procedure is being performed on a postpartum or on an interval basis. Sterilizations after vaginal delivery are performed through a minilaparotomy incision at the level of the uterine fundus, usually subumbilically. Interval sterilizations are performed by laparoscopy or minilaparotomy. Culdotomy is rarely performed in the United States, primarily because it is associated with greater infectious morbidity than procedures performed using either laparoscopy or minilaparotomy.

The choice of surgical approach influences the choice of methods of tubal occlusion. For example, most procedures performed via minilaparotomy use some type of partial salpingectomy technique as the method of tubal occlusion. Most laparoscopic sterilizations use coagulation, application of silicone rubber bands, or application of clips as the method of tubal occlusion.

TUBAL OCCLUSION

THE MODIFIED POMEROY TECHNIQUE

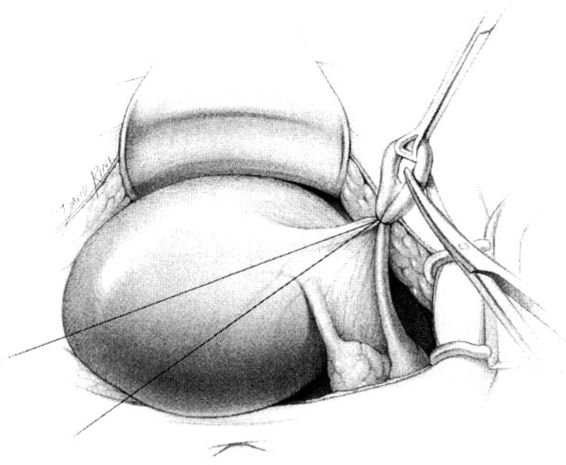

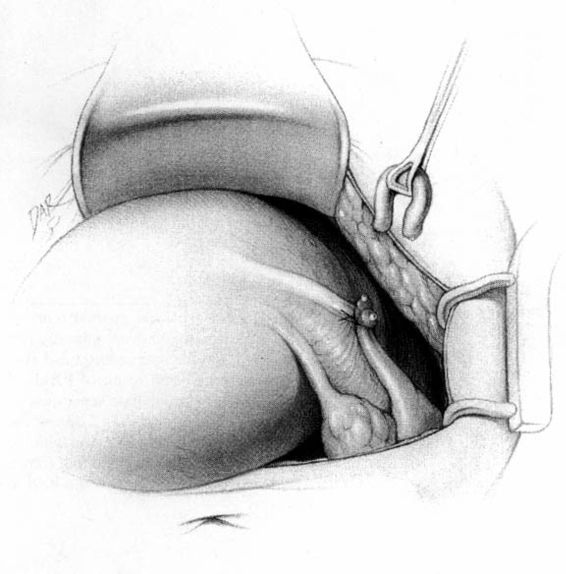

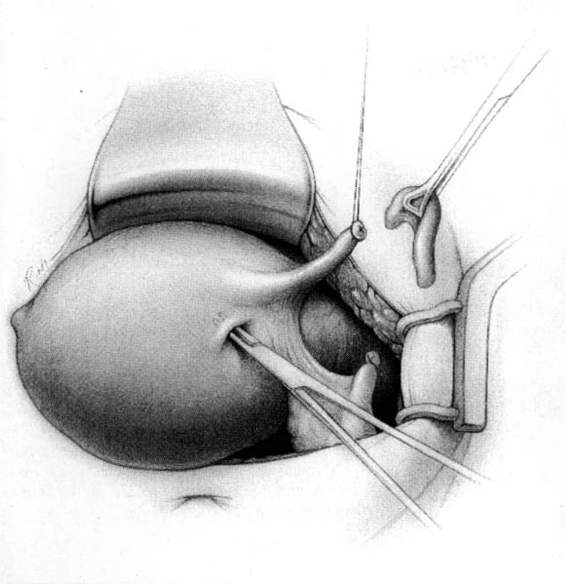

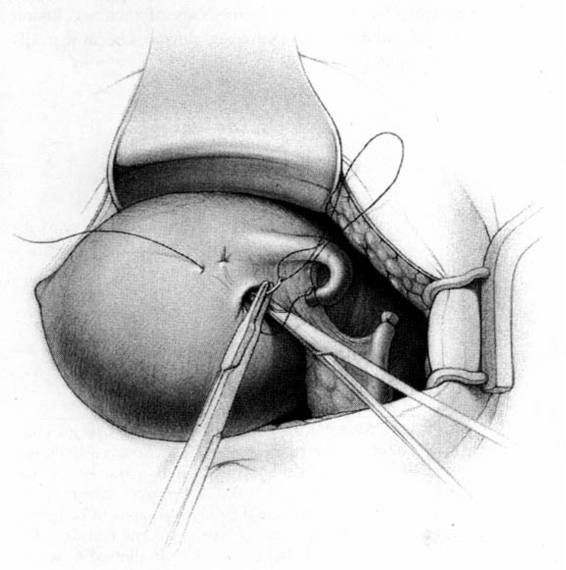

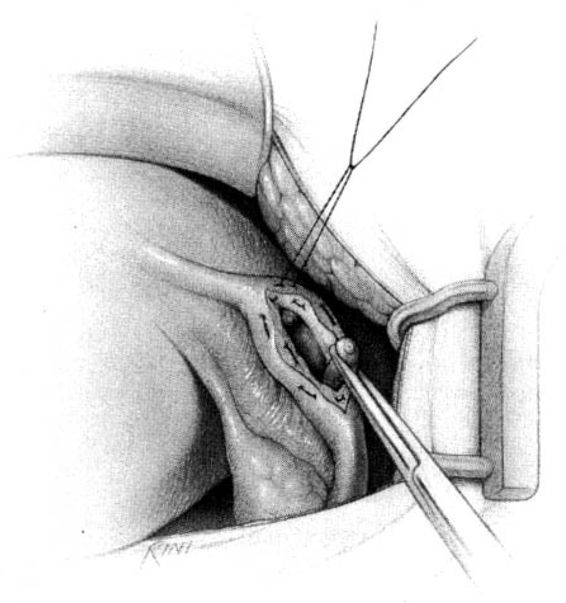

The method of tubal occlusion used by Pomeroy was described in 1930 by his colleagues, 4 years after his death (Bishop and Nelms, 1930). The Pomeroy technique as originally described included grasping the fallopian tube in its midportion and then ligating the loop of tube thus created with a double-strand of No. 1 chromic catgut suture. As with all methods of tubal occlusion, it is critical that the fallopian tube be conclusively identified. This can be accomplished by visualizing the fimbriated portion of the tube and identifying the round ligament as separate structures. The original description of the Pomeroy technique noted the importance of using absorbable sutures so that the tubal ends would separate quickly after surgery. This rationale is the main reason that the most popular modification of the Pomeroy technique involves the use of No. 1 plain catgut suture instead of chromic catgut suture. In performing the procedure, care should be taken to make the loop of fallopian tube sufficient in size to assure that complete transection of the tubal lumen will occur. After the loop of fallopian tube is ligated, the mesosalpinx of the ligated loop should be perforated using scissors (Fig. 22-1). Each ligated portion of the tube is then individually transected (Fig. 22-2). It is important not to resect the fallopian tube so close to the suture that the remaining portion of the fallopian tube slips out of the ligature and causes delayed bleeding. After the procedure, complete transection of the fallopian tube can be assured by passing a chromic suture through the lumen of the resected specimen.

FIGURE 22-1. Pomeroy tubal ligation. Midportion of tube is grasped and elevated with a Babcock clamp. The base of the loop of tube is tied with plain catgut suture and a window in the mesosalpinx is created with the tips of the scissors.

FIGURE 22-2. Pomeroy tubal ligation (continued). Each limb of the tubal loop is individually cut, and the tubal segment is removed. After hemostasis is assured, the long tails of the suture ligature are cut. If operating through a minilaparotomy incision, the tubal stumps retract back into the abdominal cavity.

THE PARKLAND METHOD

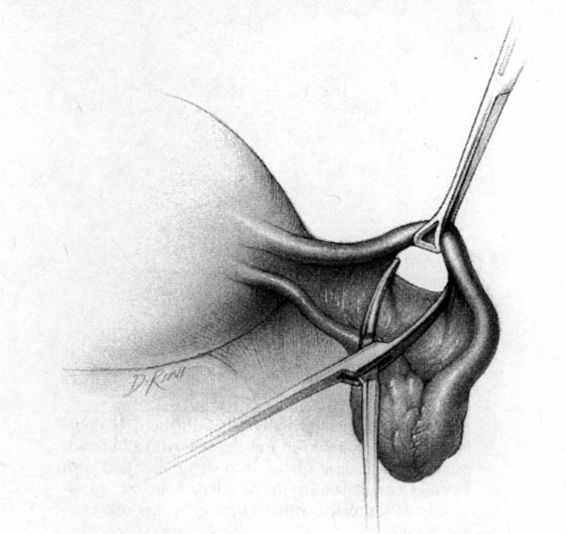

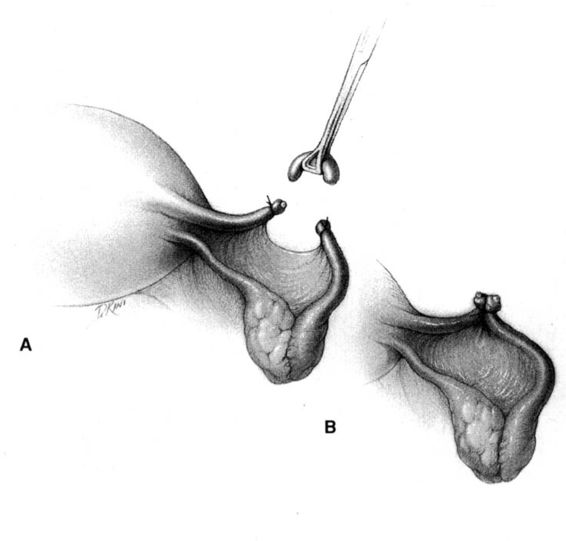

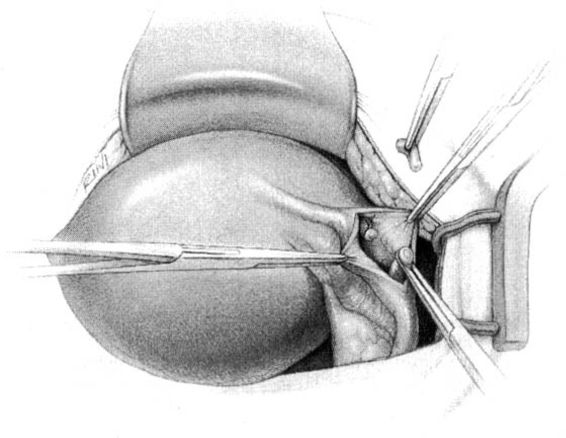

In the Parkland method of partial salpingectomy (Cunningham and associates, 1993) the tube is first conclusively identified and then grasped in its midportion. A hemostat is used to bluntly create a window in the avascular portion of the mesosalpinx just beneath the tube. The window is stretched to approximately 2.5 cm in length by opening the hemostat (Fig. 22-3). Ligatures of No. 0 chromic catgut are then passed through the window, and ligation of a proximal and distal portion of the fallopian tube is performed. The intervening segment of tube (approximately 2 cm) is then resected. In contrast with the modified Pomeroy technique, in which the resected portion of tubes are ligated together and then separated after the suture weakens, immediate separation of the tubal ends is accomplished with this method (Fig. 22-4).

FIGURE 22-3. Parkland method. An opening in the mesosalpinx is made and then stretched using a hemostat.

FIGURE 22-4 Parkland method (continued). A. Proximal and distal chromic ties are applied, and the intervening tubal segment is removed. End result of Parkland method, with the immediate separation of the tubal stumps, is shown. B. Contrast the end result of the Parkland method with the end result of the Pomeroy method, shown here, where the cut tubal ends are held in proximity.

THE IRVING PROCEDURE

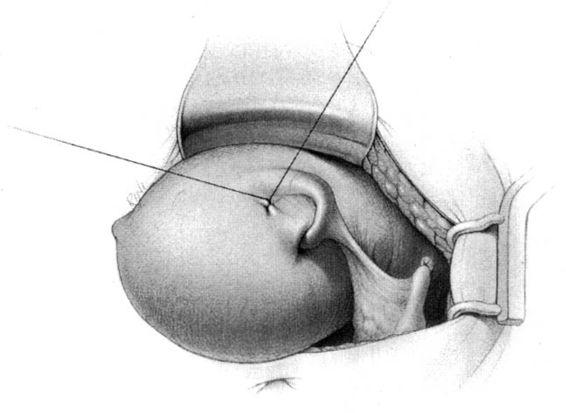

Irving first reported his sterilization technique in 1924 and later, in 1950, reported a modification of his original procedure (Irving, 1950). In the modified procedure, a window is created in the mesosalpinx and the fallopian tube is doubly ligated with No. 1 chromic catgut. The fallopian tube is then divided approximately 4 cm from the uterotubal junction; the two free ends of the ligation stitch on the proximal tubal segment are held long. The proximal portion of the fallopian tube is dissected free from the mesosalpinx and then buried into an incision into the myometrium of the posterior uterine wall, near the uterotubal junction. This is accomplished by first creating a tunnel approximately 2 cm in length with a mosquito clamp (Fig. 22-5). The two free ends of the ligation stitch on the proximal tubal segment are then separately threaded onto a curved needle, brought deep into the myometrial tunnel, and brought out through the uterine serosa (Fig. 22-6). Traction is then placed on the sutures to draw the proximal tubal stump into the myometrial tunnel; tying the free sutures fixes the tube in that location (Fig. 22-7). The opening of the myometrial incision is plicated closed using fine absorbable sutures, taking care not strangulate or damage the fallopian tube. No treatment of the distal tubal stump is necessary, but some choose to bury that segment in the mesosalpinx.

FIGURE 22-5. Irving method. Tube is tied and cut at a location giving sufficient length for the proximal tubal segment to be turned back and buried into uterus. Mosquito clamp bluntly prepares tunnel in myometrium for tube burial.

FIGURE 22-6. Irving method (continued). Suture tails from the proximal tube ligature are held long and individually loaded onto a needle. Each suture is brought deep into the myometrial tunnel and out through the uterine serosa.

FIGURE 22-7. Irving method (continued). Traction on the suture pulls the end of the proximal stump deep into the myometrial tunnel. The suture is then tied. Gaping of the myometrial tunnel around the tube, if present, can be approximated with fine absorbable suture, taking care to not damage or constrict the tube.

UCHIDA PROCEDURE

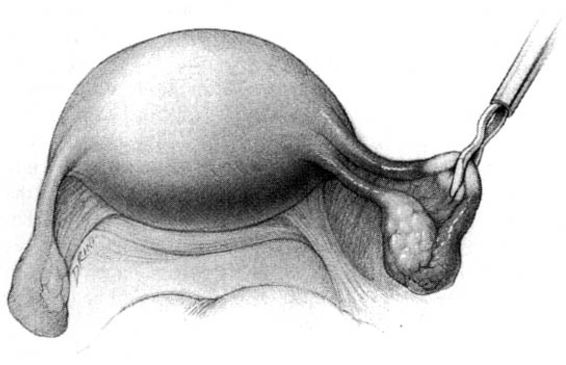

Uchida first described his procedure in 1961 and later modified it in 1975 (Uchida, 1975). In the Uchida procedure, the fallopian tube is grasped approximately 6–7 cm from the uterotubal junction. A 1:1000 epinephrine in saline solution is injected subserosally and the serosa is then incised. The muscular portion of the fallopian tube is grasped with a clamp and divided. The serosa over the proximal tubal segment is bluntly dissected toward the uterus, exposing approximately 5 cm of the proximal tubal segment (Fig. 22-8). The tube is then ligated with chromic suture near the uterotubal junction, and approximately 5 cm of the tube is resected. The shortened proximal tubal stump is allowed to retract into the mesosalpinx. The serosa around the opening in the mesosalpinx is sutured in a purse string with a fine absorbable stitch; when the suture is tied, the mesosalpinx is gathered around the distal tubal segment. This both ligates the distal tubal segment and fixes it in a position open to the abdominal cavity (Fig. 22-9). Although Uchida added fimbriectomy to the procedure in 1975, some surgeons choose to omit this step and to excise only 1 cm of fallopian tube (rather than the recommended 5 cm) in order to increase the likelihood that any future attempt at tubal reanastomosis would be successful.

FIGURE 22-8. Uchida method. After subserosal injection with dilute epinephrine (not shown), the serosa over the antimesenteric side of the tube is incised longitudinally, and the muscular tube is identified. A hemostat is held on the distal tubal segment, and the proximal segment is ligated. The intervening segment of tube is cut and removed. The proximal stump, with ligature, is then allowed to retract back into the mesosalpinx.

FIGURE 22-9. The purse string suture applied along the edge of the opened tubal serosa is tied, and the hemostat on the distal tube is removed. This closes the proximal tube in a retroperitoneal position, and simultaneously fixes and ligates the cut end of the distal tube in an extraperitoneal location.

COAGULATION

UNIPOLAR COAGULATION

Initially, all laparoscopic sterilizations were performed with unipolar coagulating instruments. However, with reports of electrical complications, particularly thermal bowel injury, the popularity of unipolar coagulation approach dropped dramatically when alternative methods of tubal occlusion (bipolar coagulation and mechanical devices) became available in the mid-1970s.

As much as 5 cm of tube can be destroyed with a single burn using the unipolar coagulating system. Thus, the isthmic-ampullary portion of fallopian tube should be grasped with the unipolar coagulating forceps at least 5 cm from the uterus. The tube should be identified with certainty. The jaws of the grasping forceps should completely encircle the fallopian tube and include a portion of the mesosalpinx as well. The fallopian tube should be carefully elevated from adjacent structures ensuring that bowel, bladder, vessels, and other structures are well away from the grasping forceps before current is applied. Current should be applied for approximately 5 seconds. The current should then be turned off before the grasping forceps is drawn back into the laparoscope. If a second burn is necessary, it should be applied to the proximal tubal stump and not to the distal tubal stump. In such a case, current should be applied for 3–4 seconds. The most proximal centimeter of the tube should not be coagulated, as thermal injury to this area theoretically increases the risk of tuboperitoneal fistula formation.

Some injuries to abdominal structures with use of unipolar coagulating instruments have occurred because the coagulating forceps came into direct contact with those structures. These injuries can also occur with bipolar coagulating systems. However, other injuries have occurred because of electrical properties unique to the unipolar electrocoagulation system. The two most noteworthy are injuries related to attachment of the ground plate and injuries related to use of nonconducting trocar sheaths.

In unipolar coagulating systems, both jaws of the grasping forceps are an active electrode and the return electrode is the ground plate underneath the patient’s buttocks. The patient is, therefore, an integral part of the electrical circuit. If the ground plate has only a small surface area, the electrical current will have sufficient density as it exits the body to have a thermal effect. Modern ground plates are sufficiently large to avoid this effect, but incomplete attachment of the ground plate could create a small surface area. Some, but not all, unipolar generators have built-in circuitry that senses whether the ground plate is fully or only partly attached. To reduce the risk of electrical injury, care should be taken to assure that the ground plate is properly attached.

Use of a nonconductive trocar sheath with unipolar coagulation can result in thermal injury attributable to capacitive coupling (Soderstrom, 1978). Metal trocar sheaths, which conduct current, allow for dissipation of current over the broad surface area between the metal sheath and the abdominal wall. Plastic or fiberglass sheaths will not permit such safe low density grounding. Consequently, the capacitively charged laparoscope can discharge current by contact with intra-abdominal structures such as the bowel. For this reason, metal trocar sheaths should be used with unipolar coagulating systems.

Should thermal injury to the bowel occur, it is important to recognize that the injury will extend well beyond the visibly damaged area. Small burns of the serosa of the bowel may not require repair; hospitalization for 5–7 days for observation to rule out peritonitis is required. If peritonitis is suspected, laparotomy is required. If burns to the bowel occur that are large or extend beyond the serosa, the damaged bowel should be resected instead of being oversewn. Oversewing the damaged area may result in delayed perforation and peritonitis. Segmental resection of the bowel with margins of 5 cm on either side of the burn lesion is recommended (Wheeless, 1992).

BIPOLAR COAGULATION

Rioux and Cloutier reported the use of bipolar coagulation for tubal sterilization in 1974 (Rioux and Cloutier, 1974). With bipolar coagulation, one jaw of the grasping forceps is the active electrode and the other jaw is the return electrode. Although any structure coming into contact with both jaws of the forceps (including the bowel) could be coagulated, the electrical properties of the bipolar system provide a safety advantage over the unipolar system. Bipolar coagulation results in a more discrete injury to the fallopian tube than occurs with unipolar coagulation. Therefore, to maximize the effectiveness of bipolar coagulation, care needs to be taken to assure complete coagulation of at least 3 cm of the isthmic portion of the fallopian tube. To accomplish this, the isthmic portion of the fallopian tube should be grasped and elevated away from adjacent structures. The fallopian tube should be identified with certainty. The grasping forceps should completely encircle the fallopian tube and cover a portion of the mesosalpinx. The portion of the tube thus grasped should then be coagulated completely, followed by coagulation of at least two additional contiguous areas proximal to the first coagulated area (Fig. 22-10; Kleppinger, 1983). Theoretically, as with unipolar coagulation, to reduce the risk of tuboperitoneal fistula formation, the most proximal centimeter of the fallopian tube should not be coagulated.

FIGURE 22-10. Bipolar method. Bipolar paddles completely grasp the tube and a portion of the underlying mesosalpinx. The proximal 3 cm of the tube theoretically should be avoided.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree