Failure to Thrive

Rebecca T. Kirkland

Failure to thrive (FTT) is a sign that describes a particular problem rather than a diagnosis. The term is used to describe instances of growth failure or, more specifically, failure to gain weight in childhood, although in more severe cases linear growth and head circumference may be affected. As stated by Perrin et al., the underlying cause is “insufficient usable nutrition.” FTT differs from other causes of poor weight gain or growth failure because of its lack of obvious organic etiology. FTT is attributed to a child usually younger than 2 years whose weight is below the fifth percentile for age on more than one occasion or whose weight is less than 80% of the ideal weight for that age, using the standard growth charts of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). An inadequate rate of weight gain that results in the crossing of two percentiles line over time indicates FTT. Updated growth charts are available from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) web site at http://www.cdc.gov.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

FTT is a problem common in pediatric practice, and it accounts for 1% to 5% of all referrals to children’s hospitals or tertiary centers. In a rural primary-care setting, 10% of children in the first year of life have had failure to thrive. FTT occurs more frequently among children living in poverty. Up to one-third of cases of FTT in some groups may be undiagnosed.

PATHOGENESIS

Organic versus Nonorganic Etiologies

The distinction between organic causes of FTT and nonorganic or psychosocial etiologies has limited usefulness. In the child with congenital heart disease or other chronic disease, the nonorganic or environmental factors also may contribute to the FTT and should not be overlooked. Likewise, the child within an emotionally disturbed family also may have an organic problem. One-third to more than one-half of cases of FTT investigated in tertiary-care settings and almost all the cases in primary-care settings have nonorganic etiologies. About one-fourth of all cases include a combination of organic and psychosocial factors. In addition, children with FTT of any etiology have significant diminishment of immunologic function and an increased susceptibility for acquiring infections. Studies show that stunted children have higher cortisol levels than nonstunted children, which may contribute to immune responses and to behavioral responses and mental health symptoms.

DIAGNOSIS

A careful, thorough history and physical examination (Table 131.1) of the child whose only sign may be a diminished weight allows a logical, rational approach to the ordering of

laboratory tests and other investigations. Observing the infant at times other than feeding, as well as during feeding, and of the interaction of the child with guardian or parent, and making an assessment of the nutritional, social, and environmental factors yields valuable information regarding the physical ability to feed and swallow as well as the psychosocial milieu. In the absence of evidence for an organic problem in the initial history and physical examination, subsequent laboratory investigation is unlikely to reveal an organic cause.

laboratory tests and other investigations. Observing the infant at times other than feeding, as well as during feeding, and of the interaction of the child with guardian or parent, and making an assessment of the nutritional, social, and environmental factors yields valuable information regarding the physical ability to feed and swallow as well as the psychosocial milieu. In the absence of evidence for an organic problem in the initial history and physical examination, subsequent laboratory investigation is unlikely to reveal an organic cause.

TABLE 131.1. CLINICAL APPROACH AND MANAGEMENT FOR FAILURE TO THRIVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

History

The pediatric history of the patient who fails to thrive should include an elicitation of symptoms suggesting organic diseases. A detailed environmental assessment is essential. Adverse psychosocial circumstances are known to have an association with diminished weight gain and growth in infancy.

A detailed nutritional and feeding history includes information related to duration of feeding time, quantity of food consumed, type of food, and to efficiency of breast-feeding in the breast-fed infant. A deficient caloric intake due to increased losses of nutrients in the stool (malnutrition or diarrhea), vomiting or regurgitation, or impaired utilization can be clarified. A history of food preferences may indicate an avoidance of foods with certain textures. This may suggest an underlying dysfunction that the child is unable to elucidate; for example, the elimination of specific foods from the diet without adequate explanation may present in a child with inflammatory bowel disease, who may avoid foods that cause abdominal discomfort without verbalizing that those foods cause pain. A history of excessive low-calorie liquid or fruit juice ingestion may indicate inappropriate nutrient intake with losses due to fructose and sorbitol malabsorption. A history may reveal an inadequate intake of protein and vitamins in some vegetarian diets. A report of food allergies may lead to the inappropriate restriction of a certain nutrient. An assessment of the parents’ knowledge of appropriate nutrition for an infant or child may reveal significant gaps and errors. If a psychosocial problem is suspected, caution should be used when interpreting a dietary history, because parental guilt may result in inaccuracies.

The psychosocial history should include an assessment of the true caretakers and family composition (absent parents), employment status, financial state, degree of social isolation (absence of a telephone or of nearby neighbors), and family stress. Poverty indicators, including eligibility for the Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), should be sought. The history should include whether adequate food is available in the home or whether the caregiver runs out of food on occasion. Maternal factors relating to the pregnancy, such as planned or unplanned pregnancy, young maternal age, use of medications for illness, substance abuse, physical or mental illness, postpartum depression, or inadequate breast milk, may be significant. A maternal history of being abused as a child or of eating disorders may be significant. Assessment should be made of levels of knowledge about parenting and about how to provide an adequate diet.

Predisposing factors in the infant are low birth weight, intrauterine growth retardation, perinatal stress, prematurity, one of a multiple birth cohort, chronic disease, and frequency of intercurrent illness such as diarrhea, vomiting, or otitis media. In the dynamic interaction between the parent and the child, factors in the child, such as being “difficult,” chronically ill, or giving diminished feedback, may contribute to the overall problem. Questions regarding the child’s sleep pattern, other behaviors, and the amount of time spent alone may be helpful. Mothers who are stressed may use breast-feeding for their comfort as well as for the infant’s comfort. In these situations, the stress may diminish the breast-milk supply, leading to frequent breast-feeding and food refusal with poor weight gain in an infant who is referred to as the “vulnerable child.”

Family members’ heights and weights, their history of illness, and any developmental delay in family members that may contribute to slow growth or constitutional short stature should be included in the assessment. Shorter parental height and higher parity have been shown to be related to slower weight gain in the infant in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Support systems available to the family and frequency home-address changes should be examined. Initially, parents may avoid mentioning psychosocial problems such as marital discord or spousal abuse; the discussion of such issues should take place during several visits. These conversations should be conducted in a nonthreatening manner, demonstrating concern and compassion.

Simple Observation

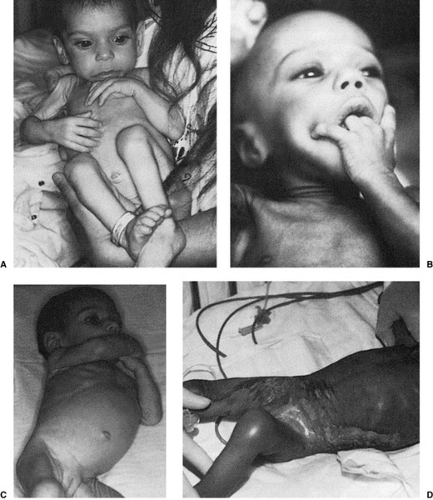

The infant’s behavior can give valuable clues regarding his ability to interact appropriately for age. Behavioral features suggestive of psychosocial or environmental deprivation may include avoidance of eye contact, absence of smiling or vocalization, and a lack of interest in the environment (Fig. 131.1). The negative response of the child to cuddling and an inability to be comforted may indicate a problem. The child may exhibit repetitive motions such as head-banging, self-stimulatory activity such as anogenital manipulation, or he may be relatively

immobile with infantile posturing. The infant may be withdrawn and socially unresponsive, even to the mother, and actually may look away from her. Some infants inappropriately seek affection from strangers. Historically, these behaviors have been described in institutionalized infants who suffer from lack of care and affection. Some infants are described as irritable secondary to malnutrition.

immobile with infantile posturing. The infant may be withdrawn and socially unresponsive, even to the mother, and actually may look away from her. Some infants inappropriately seek affection from strangers. Historically, these behaviors have been described in institutionalized infants who suffer from lack of care and affection. Some infants are described as irritable secondary to malnutrition.

Observing the mother feeding the child may be helpful. Does she cuddle the infant or merely “prop” the bottle? Does she allow sufficient time for feeding? The parents’ level of concern may be inappropriate if they are eager to relinquish the child to the health team quickly. Observing the parents’ interactions with each other will indicate whether they are supportive of each other. Observing the child feeding can indicate oral motor or swallowing difficulties. Prolonged duration of feedings or an intolerance for foods of certain textures may suggest a mild neurologic dysfunction. The setting for eating may not be optimal for the child who is easily distracted. Feeding the child in front of the television set may distract the child from eating.

Physical Examination

An accurate assessment of the child’s height, weight, and head circumference is essential. In the child younger than 2 years, the recumbent length rather than the standing height should be obtained carefully. This figure, along with weight and head circumference, should be plotted on the NCHS growth charts and related to previous measurements. The NCHS growth charts are gender-specific and appropriate for all races and nationalities. Attention to the percentile curves of length, weight, and head circumference may give valuable clues to the etiology of FTT. When all measurements are below the fifth percentile, the incidence of organic disease has been noted to be 70%, with a preponderance of neurologic or systemic diseases.

Gastrointestinal disorders are more common when only the weight is below the fifth percentile. When height and weight are affected, endocrine causes or a severe nutritional problem should be suspected (see Chapter 375, Growth, Growth Hormone and Pituitary Disorders, and 377, Neuroendocrine Disorders). The single assessment of height and weight may have limited usefulness without an indication of whether the child’s pattern is deviating from the percentile or of how far below the curve the measurement may be. In intrauterine growth retardation, the child initially is small for height and weight; weight gain and growth velocity may be adequate, yet continue to be below the fifth percentile. Also, 5% of the normal population has had growth patterns at or below the fifth percentile (constitutional short stature). Therefore, determining the median age for the child’s length (height or length age) and the median age for the child’s weight (weight age) may be useful.

Gastrointestinal disorders are more common when only the weight is below the fifth percentile. When height and weight are affected, endocrine causes or a severe nutritional problem should be suspected (see Chapter 375, Growth, Growth Hormone and Pituitary Disorders, and 377, Neuroendocrine Disorders). The single assessment of height and weight may have limited usefulness without an indication of whether the child’s pattern is deviating from the percentile or of how far below the curve the measurement may be. In intrauterine growth retardation, the child initially is small for height and weight; weight gain and growth velocity may be adequate, yet continue to be below the fifth percentile. Also, 5% of the normal population has had growth patterns at or below the fifth percentile (constitutional short stature). Therefore, determining the median age for the child’s length (height or length age) and the median age for the child’s weight (weight age) may be useful.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree