22.2 Eye disorders

Measurement of vision in children

The vision should be tested for each eye individually.

Repeat the test on another occasion if the test results seem inaccurate.

Assessment of a child with a possible eye problem

Examination

Most eyelid, eyelash and ocular surface abnormalities can be detected by observation. Many intraocular abnormalities can be detected by examination of the ‘red reflex’. This is the red to orange colour seen within the pupil when the line of illumination and observation are approximately coaxial (that is, the same). This situation is most easily obtained by observing the child’s eye with a direct ophthalmoscope from a distance of about 1 m. The light reflex for each eye can be compared. A dull or absent red reflex indicates an opacity, such as a cataract, in the normally clear media of the eye. A white reflex results from an abnormally pale reflecting surface within the eye, such as a white retinal tumour (retinoblastoma; Fig. 22.2.1) Although these intraocular disorders are rare, they are important in terms of the severe effect on vision or threat to life.

Misalignment of the eyes

Strabismus or squint occurs in 3–4% of children. Observation will confirm the presence of a large-angle strabismus. However, a broad nasal bridge or prominent epicanthic folds will mimic milder degrees of strabismus, especially in younger infants. This condition is known as pseudostrabismus (Fig. 22.2.2). The epicanthic folds cover the sclera on the medial aspect of the globe, while the lateral sclera is easily visible. This creates the appearance of misalignment, particularly when the child looks laterally. Examination of the symmetry of corneal light reflections will aid in determining whether there is an esotropia (in-turning of the eyes) or only pseudostrabismus.

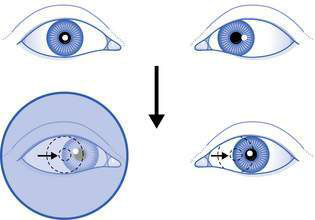

A cover test is a reliable method of detecting strabismus. The cover test is done by first getting the child to fix on an object while the observer determines which eye appears to be misaligned. The eye that appears to be fixing on the object (and not misaligned) is then covered while the apparently misaligned eye is observed. If strabismus is present, a corrective movement of the misaligned eye will be seen as this eye takes up fixation on the object of regard (Fig. 22.2.3). If no movement is seen, the eye is uncovered.