External Cephalic Version

External cephalic version, described in the medical literature since the writings of Hippocrates, was a commonly performed procedure earlier in the twentieth century (Friedlander, 1966; Hibbard and Schumann, 1973; Ranney, 1973; Stevenson, 1951). However, in the 1960s and 1970s, external cephalic version fell out of favor because of increasing reports of maternal and fetal complications, high rates of spontaneous conversion to cephalic presentation, and spontaneous reversion to breech after successful external cephalic version (Brosset, 1956; Bradley-Watson, 1975; Berg and Kunze, 1977). Furthermore, external cephalic version was being contrasted with vaginal breech delivery, which at the time was considered a totally acceptable approach to the breech presentation. Data then emerged that suggested that vaginal breech delivery was associated with excess perinatal morbidity and mortality even when congenital anomalies associated with breech presentation were excluded (Myers, 1986; Cheng 1993; Tank, 1971; Rovinsky, 1973; Brenner, 1974; Mayer, 1978; and their colleagues). Long-term follow-up of the vaginally delivered breech also revealed evidence of neurologic damage that had been undetected in the perinatal period (Berendes, 1965; Muller, 1971; Manzaki, 1978; and their coworkers), and analysis suggested that the poorer outcome resulted from the type of delivery rather than breech presentation itself (Gifford, 1995b; Mahomed, 1990; and their colleagues).

The obstetric community, not surprisingly, responded with almost universal cesarean delivery for intrapartum breech presentation, irrespective of gestational age (Taffel and associates, 1991), and breech presentation became a major component of a significantly increasing cesarean rate (Shiono and colleagues, 1987). Some physicians continued to embrace the concept of vaginal breech delivery but, even when various protocols for “safe” vaginal delivery were applied, most cases of breech presentation ultimately defaulted to cesarean delivery (Zatuchni, 1965; Bird, 1975; Collea, 1978; Gimovsky, 1980; and their associates). By 1989, 84 percent of all intrapartum breeches were managed by cesarean delivery (Taffel and colleagues, 1991). However, controversy remains regarding perinatal morbidity and mortality with breech delivery and whether routine cesarean delivery is indicated for all breech deliveries (Schiff, 1996; Koo, 1998; Albrechtsen, 1997; Daniel, 1998; Roman, 1998; Irion, 1998; Diro, 1999; Hofmeyr, 2000; and their colleagues). However, in a recent multicenter trial, it was concluded that planned cesarean delivery was better than planned vaginal breech delivery (Hannah and colleagues, 2000). Regardless of the continued “academic debate” over mode of the delivery for the breech presentation, the cesarean delivery rate in the United States for breech presentation probably now approaches 95 percent for most hospitals.

If there were not excess maternal morbidity/mortality and excess expense with cesarean delivery (Petitti, 1982; Zhang, 1993; and their coworkers), alternative approaches to the breech presentation would probably never have been sought. Because the problem seemed to be the breech presentation itself, strategies to convert the presentation to the safer cephalic presentation seemed logical. External cephalic version was thus resurrected in the past decade. Successful version rates from various institutions of 55–80 percent resulted in parallel reductions in intrapartum breech presentation and subsequent cesarean delivery (Van Dorsten, 1981; Stine, 1985; Morrison, 1986; Savona-Ventura, 1986; Robertson, 1987; Norche, 1998; Ben-Arie, 1995; Megory, 1995; Annapoorna, 1997; and their colleagues).

It should also be noted that birth injury can occur even when cesarean delivery is performed for breech presentation and thus cesarean delivery itself is not “risk free” (Cheng, 1993; Gifford, 1995; and their associates).

HISTORY OF EXTERNAL CEPHALIC VERSION

In the mid-1960s, the state of external cephalic version was best characterized by MacArthur: “There are those who enthusiastically recommend it, others who violently oppose it, and still others who express a rather elegant distaste for it” (MacArthur, 1964). Skepticism was grounded in the following:

1. Fetal risk in the form of placental separation or cord accident (Bradley-Watson, 1975; Berg and Kunze, 1977).

2. Suspected high rate of spontaneous conversion from breech to cephalic presentation if external cephalic version were not attempted (Brosset, 1956).

3. Suspected high rate of spontaneous reversion to breech presentation after successful external cephalic version (Brosset, 1956).

4. Poor success rates if attempted later in pregnancy (Ranney, 1973).

To circumvent some of these problems and to rekindle interest in external cephalic version, Saling and Muller-Holve (1975) reported a series of patients who had undergone external cephalic version under tocolysis near term. They selected term patients so that in the unlikely event of fetal distress, the fetus would be mature enough for immediate delivery. Aware of others’ poor success late in pregnancy, they employed the β-sympathomimetic fenoterol to relax the uterus and minimize the amount of force required. These authors succeeded in 75 percent of version attempts without apparent maternal, fetal, or neonatal ill-effects, and reduced term intrapartum breech presentations to 1.6 percent during the study period, as compared to 3.8 percent in the era immediately preceding. Investigators from Finland and Sweden corroborated these findings (Fall and Nilsson, 1979; Ylikorkala and Hertiakinen-Sorri, 1977); still, skeptics questioned the role of external cephalic version and cited the lack of randomized prospective trials.

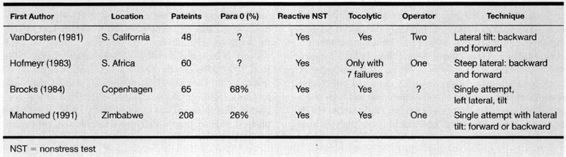

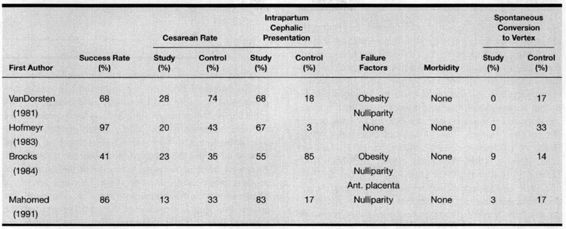

Beginning with Van Dorsten and associates (1981), four randomized prospective trials worldwide, including a total of 570 patients, have tested the role of external cephalic version at term (Hofmeyr, 1983; Brocks, 1984; Mahomed, 1991; and their colleagues). All studies were of similar design and all showed a significant reduction in both intrapartum breech presentation and cesarean delivery rate (Tables 10–1 and 10–2). The higher the institutional cesarean rate for breech presentation, the greater is the impact of external cephalic version. For example, Morrison and colleagues (1986) employed external cephalic version routinely in term breech presentation. External cephalic version was performed on 2.3 percent of all patients between 1982 and 1984. Vaginal breech deliveries decreased from 1.8 percent to 1.1 percent and cesarean delivery for breech presentation fell from 2.8 percent to 1.6 percent as compared to the three preceding years when external cephalic version was not employed. Using the most conservative estimates from the North American and European randomized trials, Hofmeyr (1991a) estimated that in the United Kingdom, “every 100 external cephalic versions at term should prevent 34 breech births and 14 cesarean sections. If external cephalic version at term were attempted in only 2 percent of the 750,000 pregnancies in the United Kingdom each year, these 15,000 external cephalic version attempts should reduce the number of breech births by 5100 and the number of cesarean sections by 2100.” With higher cesarean delivery rates in the United States, the effect of a program of successful external cephalic version should be even more dramatic.

TABLE 10-1. External Cephalic Version: Randomized Prospective Trials

TABLE 10-2. External Cephalic Version: Randomized Prospective Trials

Zhang and coworkers (1993) reviewed 25 studies published in the last 12 years, 13 of which were conducted in the United States. Based on the 1339 patients from US studies and a 64.5 percent success rate with version, they hypothesized that for every 100 normal pregnant women with a breech presentation in a program of external cephalic version, 63.3 percent (95 percent CI 60.7–65.9) would deliver vaginally and 36.7 percent (95 percent CI 34.1–39.3) would delivery by cesarean. Among controls, the overall cesarean delivery rate was 83.2 percent (95 percent CI 79.8–86.6), which is in agreement with the current cesarean birth rate for breech presentation in the United States.

The same review article included a cost analysis on a hypothetical of 100 normal pregnant women with breech presentation at term. Based on costs of uncomplicated deliveries at the North Carolina Memorial Hospital, a program of external cephalic version would save $583 per birth (12.3 percent of the total cost). This analysis did not account for any extension of hospitalization from a complicated delivery.

These authors further speculated on the ultimate impact of external cephalic version on the national cesarean rate. Using data from US studies, they concluded that a reduction in the cesarean rate among patients with term breech presentation from 83.2 percent to 36.7 percent would reduce the overall cesarean birth rate by only 1.9 percent of deliveries. A decision analysis by Gifford and colleagues (1995a) also confirmed the cost-effectiveness of a program of external cephalic version.

The safety of external cephalic version at term is established. The risk to the fetus is quite small. In a review of 979 cases of external cephalic version at term, Hofmeyr (1991b) reported no fetal losses in cases in which anesthesia had not been used. Whatever risks external cephalic version might pose, they must be weighed against the risk of persistent breech presentation. There is probably inherent risk to vaginal breech delivery (Brenner, 1974; Rovinsky, 1973; Tank, 1971; Mayer, 1978; Gifford, 1995b; Mahomed, 1990; and their colleagues). There is also the risk of precipitate delivery before arrival in the hospital and the increased risk of prolapsed cord. There is also a risk of birth trauma at cesarean and possibly increased risk of pulmonary hypertension (Tatum, 1985; Heritage, 1985; and their coworkers). In spite of the safety and efficacy of external cephalic version for breech presentation, it must be emphasized that there is also an inherent risk of breech presentation per se unrelated to version or mode of delivery (Krebs, 1999; Ismail, 1999; Bartlett, 2000; and their colleagues).

For the mother, the savings are more easily quantifiable. Cesarean delivery poses excess morbidity, mortality, and cost (Petitti, 1982; Zhang, 1993; Gifford, 1995a; and their associates). There is the likely possibility of a future repeat cesarean, and there is a potential for negative psychologic effect. However, this latter effect must be weighed against the disappointment of a failed external cephalic version.

Is the rate of cesarean delivery after successful external cephalic version higher than in women with primary cephalic presentations? Siddiqui and colleagues (1999), in a study of 92 women who had a successful external cephalic version and 184 controls, found no significant difference in the cesarean delivery rate (22.8 percent and 23.4 percent).

PROTOCOL

To offer a patient the option of external cephalic version, the clinician must first diagnose breech presentation. Flamm and Ruffini (1998) reported that 21 percent of term breech presentations were not detected before labor, and an additional 15 percent were not detected until after 38 weeks gestation. Greater vigilance could lower the cesarean rate for breech presentation. Most investigators have used uniform inclusion and exclusion criteria for external cephalic version at term (Van Dorsten, 1981; Morrison, 1986; Stine, 1985; Hofmeyr, 1983; Brocks, 1984; Mahomed, 1991; Flanagan, 1987; Dyson, 1986; Fortunato, 1988; Marchik, 1988; Flamm, 1991; Donald, 1990; Hanss, 1990; O’Grady, 1986; and their coworkers). Absolute contraindications include third trimester bleeding, placenta previa, fetal anomalies that put the fetus at risk for injury, oligohydramnios, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), and presenting fetus with multiple gestations. Table 10-3 lists the relative contraindications to external cephalic version.

TABLE 10-3. Relative Contraindications

Diabetes (β-sympathomimetics are contraindicated)

Morbid obesity

Previous uterine scar

Various positions of the fetal back (depending on the author)

Various locations of the placenta other than previa (depending on the author)

Engagement of the breech

Macrosomia

Maternal congenital or acquired heart disease (if β-sympathomimetics are employed)

Maternal thyroid dysfunction (if β-sympathomimetics are employed)

Prerequisites for elective external cephalic version include an established gestational age of 37 weeks or beyond, normal ultrasound evaluation, reactive nonstress test (NST), informed consent, and availability of an operating room and anesthetic support. Intravenous access should be established and the maternal bladder should be empty. Because of the uniformly poor rate of success of external cephalic version at term, most investigators have employed a β-sympathomimetic to relax the uterus and facilitate manipulation. Acceptable and similar success rates have been reported with a number of different agents, including nitroglycerin (Smith and Brien, 1998), whether administered subcuta-neously or intravenously. Although one randomized trial found no difference in successful version between tocolytic and placebo groups (Robertson and colleagues, 1987), four randomized prospective studies show a significant benefit to adjunctive tocolysis (Stock, 1993; Chung, 1996; Fernandez, 1997; Marquette, 1996). In cases of diabetes, magnesium sulfate has been used as a safe and satisfactory tocolytic.

TECHNIQUE

Both one- and two-person version techniques have been described. Maternal flexion at the knees and hips relaxes abdominal musculature and lateral uterine displacement prevents supine hypotension. Some authors use powder on the maternal abdomen to facilitate a better purchase on the fetal poles; other authors use a lubricant gel or olive or mineral oil so that the hands can slide over the maternal abdomen as the fetus is turned. Some favor the steep lateral position, while most use a lateral tilt. The direction of tilt often varies with the direction of the version attempt. The critical first step is elevation of the fetal breech from the maternal pelvis. If this step cannot be accomplished, success is doubtful and is not facilitated by concurrent vaginal elevation by an assistant. Success is reported with both a forward roll and back flip. If one direction is not successful, the other is usually tried. After elevation of the breech, a to-and-fro movement on appropriate poles of the fetus facilitates external cephalic version (Fig. 10-1). The patient’s pain threshold dictates how much pressure can be exerted. Anesthesia, analgesia, or sedation are controversial, as they might allow excess force to be used, causing abruption, cord accident, or uterine rupture (Bradley-Watson, 1975; Berg and Kunze, 1977).

FIGURE 10-1. After elevation of the breech, a to-and-fro movement on appropriate poles of the fetus facilitates external cephalic version.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree