Chapter Outline

History and Physical Examination

Making the Incontinence Diagnosis

Diagnostic Accuracy of Office Evaluations

Urinary incontinence can be a symptom of which patients complain, a sign demonstrated on examination, or a condition (i.e., diagnosis) that can be confirmed by definitive studies. When a woman complains of urinary incontinence, appropriate evaluation includes exploring the nature of her symptoms and looking for physical findings. The history and physical examination are the first and most important steps in the evaluation. A preliminary diagnosis can be made with simple office and laboratory tests, with initial therapy based on these findings. If complex conditions are present, if the patient does not improve after initial therapy, or if surgery is being considered, definitive, specialized studies are usually necessary.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a heterogeneous condition in which weaknesses of the pelvic floor musculature and connective tissue result in descent or bulging of pelvic organs into the vaginal canal. In more severe cases, prolapse can protrude through the vaginal introitus and beyond the hymenal ring. In anterior vaginal wall prolapse , the bladder and urethra may potentially protrude into the vaginal canal (cystocele). Patients may have uterine prolapse or, after hysterectomy, the vaginal cuff may herniate resulting in apical vaginal prolapse . The rectum, small bowel, and sigmoid colon also may herniate in posterior vaginal wall prolaps e, resulting in rectoceles, enteroceles, and sigmoidoceles, respectively. That said, terminologies such as “cystocele” and “rectocele,” although commonly used in clinical practice, are perhaps less precise because they imply an unrealistic certainty as to the specific organs behind the vaginal wall at the time of physical examination.

Definitions of prolapse as a clinical condition or disease are based on measured severity or staging by Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ; see Chapter 8 ) examination and by assessment of relevant symptoms. Although most clinicians can recognize the extremes of normal support versus severe prolapse, most cannot objectively state at what point vaginal laxity become pathologic and require intervention. There are limited data concerning the normal distribution of POP in the population and the correlations between symptoms and physical findings. In a study of 497 women, demonstrated that the distribution of prolapse in a population exhibited a bell-shaped curve, with the majority of women having Stage I or II prolapse by the POPQ classification system and only 3% having Stage III prolapse. This signifies that, at baseline, a majority of women, especially those who have borne children, have some degree of pelvic relaxation. However, these women are generally asymptomatic and will only develop symptoms as their prolapse increases in severity, especially as it protrudes to the hymen and beyond ( ). Therefore, even if prolapse is found on physical examination, it may not be clinically relevant and may not require intervention if the patient is asymptomatic.

proposed that POP, the disease , be defined as the descent of one or more of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina beyond the hymen on straining examination (the sign of POP) associated with feeling or seeing a bulge from the vagina during daily activities (the symptom of POP). Patients with descent beyond the hymen who do not have bulge symptoms would be classified as having asymptomatic POP and those with bulge symptoms should be classified as having symptomatic POP.

History and Physical Examination

History of Urinary Incontinence

Early in the interview, one should elicit a description of the patient’s main complaint, including duration and frequency. A clear understanding of the severity of the problem or disability and its effect on quality of life should be sought. Assessment of mobility and living environment is especially important in certain patients. Questions should be asked about access to toilets or toilet substitutes and about social factors such as living arrangements, social contacts, and caregiver involvement.

Box 9.1 lists questions that are helpful in evaluating incontinence in women. The first question is designed to elicit the symptom of stress incontinence (i.e., urine loss with events that increase intraabdominal pressure). The symptom of stress incontinence is usually (but not always) associated with the diagnosis of urodynamic stress incontinence. Questions 2 through 9 help elicit the symptoms associated with detrusor overactivity. The symptom of urge incontinence is present if the patient answers question 3 affirmatively. Frequency (questions 4 and 5), bedwetting (question 6), leaking with intercourse (question 8), and a sense of urgency (questions 2 and 7) are all associated with detrusor overactivity. Questions 9 and 10 help to define the severity of the problem. Questions 11 through 13 screen for urinary tract infection and neoplasia, and questions 14 through 16 are designed to elicit symptoms of voiding dysfunction.

- 1.

Do you leak urine when you cough, sneeze, or laugh?

- 2.

Do you ever have such an uncomfortably strong need to urinate that if you don’t reach the toilet you will leak?

- 3.

If “yes” to question 2, do you ever leak before you reach the toilet?

- 4.

How many times during the day do you urinate?

- 5.

How many times do you void during the night after going to bed?

- 6.

Have you wet the bed in the past year?

- 7.

Do you develop an urgent need to urinate when you are nervous, under stress, or in a hurry?

- 8.

Do you ever leak during or after sexual intercourse?

- 9.

How often do you leak?

- 10.

Do you find it necessary to wear a pad because of your leaking?

- 11.

Have you had bladder, urine, or kidney infections?

- 12.

Are you troubled by pain or discomfort when you urinate?

- 13.

Have you had blood in your urine?

- 14.

Do you find it hard to begin urinating?

- 15.

Do you have a slow urinary stream or have to strain to pass your urine?

- 16.

After you urinate, do you have dribbling or a feeling that your bladder is still full?

After the urologic history, thorough medical, surgical, gynecologic, neurologic, and obstetric histories should be obtained. Certain medical and neurologic conditions, such as diabetes, stroke, and lumbar disk disease, may cause urinary incontinence. Furthermore, strong coughing associated with chronic pulmonary disease can markedly worsen symptoms of stress incontinence. A bowel history should be noted because chronic severe constipation has been associated with voiding difficulties, urgency, stress incontinence, increased bladder capacity, and POP. A history of hysterectomy, vaginal repair, pelvic cancer and/or radiotherapy, or surgery for incontinence should alert the physician to the possibility of prior surgical trauma to the lower urinary tract.

A complete list of the patient’s medications (including nonprescription medications) should be sought to determine whether individual drugs might influence the function of the bladder or urethra, leading to urinary incontinence or voiding difficulties. A list of drugs that commonly affect lower urinary tract function is shown in Table 9.1 . In these cases, altering drug dosage or changing to a drug with similar therapeutic effectiveness but with fewer lower urinary tract side effects, will often improve or “cure” the offending urinary tract symptom.

| Type of Medication | Lower Urinary Tract Effects |

|---|---|

| Diuretics | Polyuria, frequency, urgency |

| Caffeine | Frequency, urgency |

| Alcohol | Sedation, impaired mobility, diuresis |

| Narcotic analgesics | Urinary retention, fecal impaction, sedation, delirium |

| Anticholinergic agents | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

| Antihistamines | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Psychotropic agents | |

| Antidepressants | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Antipsychotics | Anticholinergic actions, sedation |

| Sedatives/hypnotics | Sedation, muscle relaxation, confusion |

| Alpha-adrenergic blockers | Stress incontinence |

| Alpha-adrenergic agonists | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

| Calcium-channel blockers | Urinary retention, voiding difficulty |

Urinary Diary

Patient histories regarding frequency and severity of urinary symptoms are often inaccurate and misleading. Urinary diaries are more reliable and require the patient to record volume and frequency of fluid intake and of voiding, usually for a one- to seven-day period. A three-day diary seems to be as accurate as a seven-day diary to document symptoms, and compliance is improved. Episodes of urinary incontinence and associated events or symptoms such as coughing, urgency, and pad use are noted. The number of times voided each night and any episodes of bedwetting are recorded the next morning. The maximum voided volume also provides a relatively accurate estimate of bladder capacity. The physician should review the frequency/volume charts with the patient and corroborate or modify the initial diagnostic impression. If excessive frequency and volume of fluid intake are noted, restriction of excessive oral fluid intake (combined with scheduled voiding) may improve symptoms of stress and urge incontinence by keeping the bladder volume below the threshold at which urinary leaking results.

Urinary diaries are a useful and accepted research method to measure the severity of incontinence and as an outcome measure after interventions. This is reviewed in Chapter 44 .

History of POP

Patients with POP may present with symptoms directly related to the prolapse such as vaginal bulge, pressure, and discomfort as well as a plethora of associated symptoms relating to voiding, defecatory, and sexual dysfunction. The severity of the prolapse is not necessarily associated with increased visceral symptomatology.

Vaginal prolapse in any compartment—anterior, apical, or posterior—can manifest as vaginal fullness, pain and/or protruding mass. In a study by , the feeling of “a bulge or that something is falling outside the vagina” had a positive predictive value of 81% for POP; the lack of this symptom had a negative predictive value of 76% for predicting prolapse at or past the hymen. Not surprisingly, increased degree of prolapse, especially beyond the hymen, is associated with increased pelvic discomfort and visualization of a protrusion. The presence of vaginal bulge symptoms is a highly specific (but not sensitive) symptom for predicting the presence of prolapse beyond the hymen on a straining examination (specificity 99% to 100%) ( ; ). The association of POPQ measures on examination with three commonly related symptoms—urinary splinting, digital assistance with defecation, and vaginal bulge—is shown in Figure 9.1 .

Stress urinary incontinence and voiding difficulties can occur in association with anterior and apical vaginal prolapse. However, women with advanced degrees of prolapse may not have overt symptoms of stress incontinence because the prolapse may cause a mechanical obstruction of the urethra, thereby preventing urinary leakage. Instead, these women may require vaginal pressure or manual replacement of the prolapse to accomplish voiding. They are therefore at risk for incomplete bladder emptying and recurrent or persistent urinary tract infections and for the development of de novo stress incontinence after the prolapse is repaired. Patients who require digital assistance to void in general have more advanced degrees of prolapse. In addition to difficulty voiding, other urinary symptoms such as urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence are found in women with prolapse. However, it is not clear whether the severity of prolapse is directly associated with more irritative voiding symptoms or bladder pain.

POP, especially in the apical and posterior compartments, can be (but are not always) associated with defecatory dysfunction, such as pain with defecation, the need for manual assistance with defecation, and anal incontinence of flatus, liquid, or solid stool. These patients often have outlet-type constipation secondary to the trapping of stool within the rectal hernia necessitating the need for splinting or applying manual pressure in the vagina, rectum, or perineum to reduce the prolapse aiding in defecation. Although defecatory dysfunction remains an area that is least understood in patients with prolapse, clinical and radiographic studies have shown that the severity of prolapse is not strongly correlated with increased symptomatology.

Although the relationship between sexual function and POP is not clearly defined, questions regarding sexual dysfunction must be included in the evaluation of any patients with prolapse. Patients may report symptoms of dyspareunia, decreased libido and orgasm, and increased embarrassment with altered anatomy that affects body image. Some studies have reported that prolapse adversely affected sexual functioning with subsequent improvement in sexual function after repair of prolapse ( ). However, showed little correlation between the extent of prolapse and sexual dysfunction. Evaluating sexual function may be especially difficult in this patient population as the hindrances to sexual function may include factors other than prolapse, such as partner limitations and functional deficits.

Symptoms of incontinence and prolapse and their impact on the woman can be measured or quantified using a number of easy-to-use and validated questionnaires measuring symptom severity, quality of life, and sexual function. These outcome measures can be useful in clinical practice and in research; they are reviewed in detail in Chapter 44 .

Gynecologic Examination

General, gynecologic, and lower neurologic examinations should be performed on every woman with incontinence and/or prolapse. The pelvic examination is of primary importance. A bimanual examination is performed to rule out coexistent gynecologic pathology, which can occur in up to two-thirds of patients. The rectal examination further evaluates for pelvic pathology and fecal impaction, the latter of which may be associated with voiding difficulties and incontinence in elderly women. Urinary incontinence has been shown to improve or resolve after the removal of fecal impactions in institutionalized geriatric patients.

The physical examination for incontinence and prolapse should be conducted with the patient in dorsal lithotomy position, as for a routine pelvic examination. If physical findings do not correspond to symptoms or if the maximum extent of the prolapse cannot be confirmed, the woman can be reexamined in the standing position.

Initially, the external genitalia are inspected, and if no displacement is apparent, the labia are gently spread to expose the vestibule and hymen. Vaginal discharge can mimic incontinence, so evidence of this problem should be sought and, if present, treated. Palpation of the anterior vaginal wall and urethra may elicit urethral discharge or tenderness that suggests a urethral diverticulum, carcinoma, or inflammatory condition of the urethra. The integrity of the perineal body is evaluated and the extent of all prolapsed parts are assessed. A retractor, Sims speculum, or the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum can be used to depress the posterior vagina to aid in visualizing the anterior vagina, and vice versa for the posterior vagina. Because most patients with prolapse are postmenopausal, the vaginal mucosa should be examined for atrophy and thinning because this may affect management. Healthy, estrogenized tissue, without significant evidence of prolapse, will be well perfused and have rugation and physiologic moisture. Atrophic vaginal tissue consistent with hypoestrogenemia appears pale, thin, without rugation, and can be friable; this finding suggests that the urethral mucosa is also atrophic.

After the resting vaginal examination, the patient is instructed to perform the Valsalva maneuver or to cough vigorously. During this maneuver, the order of descent of the pelvic organs is noted, as is the relationship of the pelvic organs at the peak of increased intraabdominal pressure. The presence and severity of anterior vaginal relaxation, including cystocele and proximal urethral detachment and mobility, or anterior vaginal scarring, are estimated. Associated pelvic support abnormalities, such as rectocele, enterocele, and uterovaginal prolapse, are noted. The amount or severity of prolapse in each vaginal segment should be measured, staged and recorded according to POPQ guidelines noted in Chapter 8 . A rectovaginal examination is recommended to fully evaluate prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall and perineal body. Digital assessment of bowel contents in the rectovaginal septum during straining examination can help to diagnose an enterocele. Other clinical observations and tests to help delineate prolapse include: cotton swab testing for the measurement of urethral axis mobility (Q-tip test); measurement of perineal descent; measurement of the transverse diameter of the genital hiatus or of the protruding prolapse; measurement of vaginal volume; description and measurement of posterior prolapse; and examination techniques differentiating between various types of defects (e.g., central versus paravaginal defects of the anterior vaginal wall). Inspection should also be made of the anal sphincter because fecal incontinence is often associated with posterior vaginal support defects. Grossly, women with a torn external sphincter may have scarring or a “dove-tail” sign on the perineal body.

Anterior vaginal wall descent usually represents bladder descent with or without concomitant urethral hypermobility. However, in 1.6% of women with anterior vaginal prolapse, an anterior enterocele can mimic a cystocele on physical examination. Furthermore, lateral paravaginal defects, identified as detachment of the lateral vaginal sulci, may be distinguished from central defects, seen as a midline protrusion with preservation of the lateral sulci, by using a curved forceps placed in the anterolateral vaginal sulci directed toward the ischial spine. Bulging of the anterior vaginal wall in the midline between the forceps blades implies a midline defect; blunting or descent of the vaginal fornices on either side with straining suggest lateral paravaginal defects. However, researchers have shown that the physical examination technique to detect paravaginal defects is not particularly reliable or accurate. In a study by of 117 women with prolapse, the sensitivity of clinical examination to detect paravaginal defects was good (92%), yet the specificity was poor (52%). Despite a high prevalence of paravaginal defects, the positive predictive value was only 61%. Less than two-thirds of women believed to have a paravaginal defect on physical examination were confirmed to possess the same at surgery. Another study by demonstrated poor reproducibility of clinical examination to detect anterior vaginal wall defects. Thus the clinical value of determining the location of midline, apical and lateral paravaginal defects remains unknown.

In regard to posterior prolapse, clinical examinations do not always accurately differentiate between rectoceles and enteroceles. Some investigators thus have advocated performing imaging studies to further delineate the exact nature of the posterior wall prolapse. Traditionally, most clinicians believe they are able to detect the presence or absence of these defects without anatomically localizing them. However, little is known regarding the accuracy or utility of clinical examinations in evaluating the anatomic locations of prolapsed small or large bowel or of specific defects in the rectovaginal space. found that clinical examinations often did not accurately predict the specific location of defects in the rectovaginal septum that were subsequently found intraoperatively. Clinical findings corresponded with intraoperative observations in 59% of patients and differed in 41%; sensitivities and positive predicative values of clinical examinations were less than 40% for all posterior defects. However, what remains unclear is the clinical consequence of not detecting these defects preoperatively.

As noted previously, the POPQ classification should be done on all women with prolapse. This descriptive system contains a series of site-specific measurements of the woman’s pelvic organ support. The measurements can be obtained quickly in both experienced and nonexperienced hands. It can be easily learned and taught by means of a brief video tutorial. Prolapse in each segment is evaluated and measured relative to the hymen (not introitus), which is a fixed anatomic landmark that can be identified consistently and precisely. The anatomic position of the six defined points for measurement should be centimeters above or proximal to the hymen (negative number) or centimeters below or distal to the hymen (positive number), with the plane of the hymen being defined as zero. For example, a cervix that protrudes 3 cm distal to (beyond) the hymen should be described as +3 cm. Studies have demonstrated excellent interexaminer and intraexaminer reliability when using the POPQ system to quantify prolapse. The POPQ system does not take into account lateral defects and perineal body prolapse, but these can be added in descriptive terms. POPQ measurements can also help predict or aid in the diagnosis of voiding dysfunction ( ) and levator hiatus ballooning ( ). Despite its limitations, POPQ system is currently the classification system used in most research studies and National Institutes of Health trials, and is gaining popularity in clinical practice.

Neurologic Examination

Urinary (and fecal) incontinence may be the presenting symptom(s) of neurologic disease. The screening neurologic examination should evaluate mental status, sensory and motor function of both lower extremities, and include a screening lumbosacral neurologic examination. The screening lumbosacral examination should include assessments of: (1) pelvic floor muscle strength, (2) anal sphincter resting tone, (3) voluntary anal contraction, and (4) perineal sensation. This simple screening examination can be performed quickly and easily as part of the gynecologic examination. When abnormalities are noted, or when an individual is suspected of having neurologic dysfunction, a comprehensive neurologic examination with particular emphasis on the lumbosacral nerve roots should be performed. This comprehensive evaluation should be performed before any neurophysiologic testing, because any such testing should only be interpreted in the context of the patient’s history and physical examination findings.

Mental status is determined by noting the patient’s level of consciousness, orientation, memory, speech, and comprehension. Disorders associated with mental status aberrations that may result in changes in bowel or bladder function include senile and presenile dementia, brain tumors, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and normal pressure hydrocephalus.

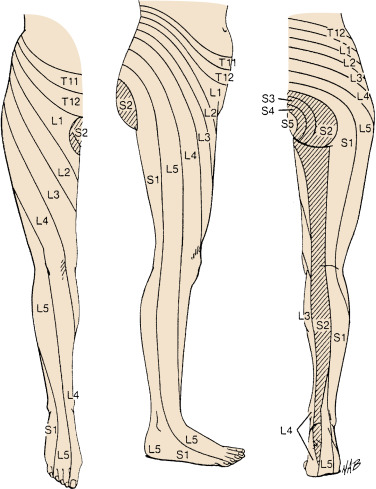

Evaluation of the sensory and motor systems may identify an occult neurologic lesion or can help determine the level of a known lesion. Common diseases associated with sensory and motor abnormalities that can produce urologic disturbances include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular disease, infections, and tumors. Sacral segments 2 through 4, which contain the important neurons controlling micturition, are particularly important ( Fig. 9.2 ). Sensory function is evaluated by testing the lumbosacral dermatomes for the ability to sense light touch, pinprick, and temperature. The sensory dermatomes of interest include the perineum and perianal skin (pudendal n., S2-4), mons pubis and upper aspect of labia majora (ilioinguinal n., L1-2), front of the knees (L3-4), and sole of the foot (S1). Dermatome maps are useful for characterizing sensory deficits, although it is important to remember that there can be considerable overlap between dermatomes. To test motor function, the patient extends and flexes the hip, knee, and ankle and inverts and everts the foot. The strength and tone of the levator ani muscle and external anal sphincter are estimated digitally. The strength of pelvic floor musculature is assessed by palpating the levator ani muscle complex in the posterior vaginal wall approximately 2 to 4 cm cephalad to the hymen. The patient is then asked to squeeze around the examiner’s fingers. Weakness in this muscle can be a result of neurologic deficits or direct trauma during childbirth. Skeletal muscle strength is graded on a scale from 0 to 5 (see Table 9.2 ). Position sense and vibration should be assessed, but need only be evaluated in the distal extremities. The patellar, ankle, and plantar reflex responses are tested.

| Score | Limb Muscles | Levator Ani |

|---|---|---|

| 0/5 | No movement | No contraction |

| 1/5 | Trace of contraction | Flicker, barely perceptible |

| 2/5 | Active movement when gravity eliminated | Loose hold, 1-2 s |

| 3/5 | Active movement against gravity only | Firmer hold, 1-2 s |

| 4/5 | Active movement against resistance, but not normal | Good squeeze, 3-4 s, pulls fingers in and up loosely |

| 5/5 | Normal strength | Stronger squeeze, 3-4 s, pulls in and up snugly |

Visceral sensation of the bladder and rectum can be assessed with cystometry and anal manometry, respectively. Loss of perineal sensation in a patient with bowel or bladder dysfunction, particularly if acute, should always alert the examiner to a potentially serious neurologic problem. Neurophysiologic testing and/or radiologic evaluation should be performed to assess for conus medullaris or cauda equina syndrome.

Two reflexes may help in the examination of sacral reflex activity. In the anal reflex, stroking the skin adjacent to the anus causes reflex contraction of the external anal sphincter muscle. The bulbocavernosus reflex involves contraction of the bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus muscles in response to tapping or squeezing of the clitoris. Unfortunately, these reflexes can be difficult to evaluate clinically and are not always present, even in neurologically intact women.

Both the resting tone and voluntary contraction of the anal sphincter should be assessed. The examiner should first inspect the anus, looking for scarring or a gaping sphincter. Women with disruption of the external anal sphincter may have gross abnormalities of the perineal body with a “dove-tail” sign in the area of the disrupted sphincter. A digital rectal examination should be performed, noting the resistance to entry of the examining finger. Fifty percent to 85% of overall resting anal tone is generated by the internal anal sphincter. Loss of resting tone suggests disruption of the internal anal sphincter and/or an injury to its sympathetic innervation (i.e., pelvic plexus injury). The patient then should be asked to maximally squeeze her anal sphincter. The presence of a strong voluntary anal sphincter contraction indicates intact pudendal innervation and external anal sphincter. Unlike pelvic muscle strength, there is no widely accepted validated scale for quantifying anal squeeze strength. used a 0 to 3+ scale and found that it had a high correlation with maximum squeeze pressure as measured by anal manometry. used a modified version of the pelvic muscle rating scale to quantify anal squeeze strength. Absence or decrease of both anal sphincter tone and voluntary contraction suggests a possible sacral or peripheral nerve lesion. Preservation of resting tone in the absence of a voluntary contraction suggests a suprasacral lesion.

Techniques for Measuring Urethral Mobility

Examination of the anterior vaginal wall is inaccurate in predicting the amount of urethral mobility. It is difficult with physical examination to differentiate between cystocele and rotational descent of the urethra and the two often coexist. Measuring urethral mobility aids in the diagnosis of urodynamic stress incontinence and in planning treatment for this condition (bladder neck suspension or sling versus urethral injection of bulking agents).

Although pelvic examination alone is generally considered to be unreliable in predicting urethral mobility, showed that essentially all of the women with Stage II to IV prolapse by POPQ had Q-tip angle greater than 30°. Thus perhaps measures of urethral mobility would only be useful in women with Stage 0 or I prolapse or in those with prior surgical repairs or other interventions. Several tests are available for estimating the amount of urethral mobility in women.

Radiologic Assessment

Lateral cystourethrography in the resting and straining view can identify mobility or fixation of the bladder neck, funneling of the bladder neck and proximal urethra, and degree of cystocele. The voiding component can identify a urethral diverticulum, fistula, mass, obstruction, or vesicoureteral reflux. Videocystourethrography allows a dynamic assessment of the anatomy and function of the bladder base and urethra during retrograde filling with contrast material and during voiding. It is most helpful in sorting out causes of complex incontinence problems. However, it is invasive, expensive, and not widely available. For these reasons, other methods are usually used to measure urethral mobility in incontinent women.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is an alternative method of evaluating urethrovesical anatomy and is described in detail in Chapter 13 . Vaginal ultrasonography accurately displays descent of the urethrovesical junction, opening of the bladder neck, and detrusor contractions. This technique is a noninvasive and accurate method of evaluating the position and mobility of the urethrovesical junction and proximal urethra in incontinent women.

Q-Tip Test

Placement of a cotton swab in the urethra to the level of the vesical neck and measurement of the axis change with straining can be used to demonstrate urethral mobility. To perform the Q-tip test, a sterile, lubricated cotton-tipped applicator is inserted transurethrally into the bladder, then withdrawn slowly until definite resistance is felt, indicating that the cotton tip is at the bladder neck. This is best accomplished with the patient in the supine lithotomy position during a pelvic examination. The resting angle of the applicator stick in relation to the horizontal is measured with a goniometer or protractor. The patient is then asked to cough and perform a Valsalva maneuver, and the maximum straining angle from the horizontal is measured. Results are not affected by the amount of urine in the bladder. Care should be taken to ensure that the cotton tip is not in the bladder or at the mid-urethra because this results in a falsely low measurement of urethral mobility.

Although maximum straining angle measurements greater than 30° are generally considered to be abnormal, few data are available to differentiate normal from abnormal measurements. Urethral mobility in continent women is related to age, parity, and support defects of the anterior vaginal wall, and “urethral hypermobility” is common in asymptomatic women. Women with urodynamic stress incontinence have higher maximum straining Q-tip angles, although there wide overlap in measurements between the continent and incontinent women. In general, arbitrary cutoff values around 30° are too low to define “normal” urethral mobility for parous women, and this test is no longer considered useful in helping with diagnosis or treatment of incontinence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree