Evaluation of the Surgical Abdomen

“Pregnancy does not contraindicate operation. Surgical conditions arising during pregnancy, in which operation, if postponed, would endanger the life or health of the patient, should not be deferred on account of the pregnancy.”

James Warbasse (1918)

Published in a major surgical textbook in the early part of the twentieth century, this principle still remains the singular most important tenet for the care of pregnant women with surgical abdominal illnesses. In this chapter, generalizations concerning the interaction of pregnancy with some of the more common surgical abdominal diseases are reviewed, and rational approaches to their management are discussed. A recurring theme is that proven diagnostic techniques and treatments used in the care of nonpregnant patients with surgical illnesses should be promptly employed without alteration in pregnant women with similar diseases unless modification is justifiable.

EVALUATION OF THE SURGICAL ABDOMEN–POTENTIAL PITFALLS

During normal pregnancy, the gastrointestinal tract and its appendages undergo anatomic and functional changes that can alter appreciably the criteria for diagnosis and treatment of diseases to which they are susceptible. These physiologic changes may produce signs and symptoms common to both pregnancy and abdominal surgical illnesses, and represent significant potential pitfalls for the proper evaluation of the pregnant woman with a surgical abdomen.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS COMMON TO BOTH PREGNANCY AND SURGICAL ILLNESS

Pain is the most common symptom leading to evaluation of the potentially surgical abdomen. To some degree, virtually all pregnant women have abdominal pain, but it is often self-limited and has no adverse effect on pregnancy outcome. Failure to recognize pain from an underlying acute surgical illness, however, may result in significant morbidity, and even mortality. The most common obstetric cause of abdominal pain during pregnancy is labor. It is important to recognize that labor can be stimulated by a number of serious conditions. Thus, in a woman undergoing evaluation of a potential surgical abdomen, normal labor must be distinguished from other obstetric causes, such as a placental abruption, as well as from nonobstetric causes, such as acute appendicitis.

Nausea and vomiting are frequent early in normal pregnancy, but they also are symptoms classically associated with underlying abdominal diseases. Goodwin (1998) reported that 70 percent of women experience nausea and vomiting between the fourth and seventh weeks of gestation. If these symptoms are erroneously attributed to normal physiologic changes, however, serious gastrointestinal disease can be overlooked. Persistent nausea and vomiting in late pregnancy are unexpected findings and should always prompt a search for underlying pathology.

Constipation is another common symptom during pregnancy that also may be associated with underlying pathology. The small bowel has diminished motility during pregnancy. Parry and associates (1970) reported that small intestinal transit time was about 60 hours in women 12–20 weeks pregnant as compared with 52 hours in nonpregnant controls. They showed that the colon undergoes muscular relaxation as well as increased absorption of water and sodium, both of which predispose to constipation. According to Anderson and Whichelow (1985), almost 40 percent of women complain of constipation some time during pregnancy, and 20 percent do so in the third trimester. While symptoms are usually only mildly bothersome, pregnant women are occasionally encountered who develop megacolon from impacted stool. Although these latter women almost invariably abused stimulatory laxatives, Shield (1987) described a woman with recurrent megacolon during pregnancy related to Hirschsprung disease. Preventative measures for mild constipation include a high-fiber diet along with prescription of bulk-forming laxatives.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION PITFALLS

The normal physiologic adaptations of pregnancy significantly alter physical signs typically associated with abdominal surgical illnesses. Early in pregnancy, for example, vital sign measurements, which are fundamental in the evaluation of any ill patient, undergo remarkable changes. Capeless and Clapp (1989), in a longitudinal study of women before and during their pregnancy, demonstrated that the majority of the pregnancy-induced changes in cardiovascular function are demonstrable by 8 weeks’ gestation. Thus, for example, caution should be employed before attributing a low, though physiologically normal, blood pressure or hematocrit to underlying pathology.

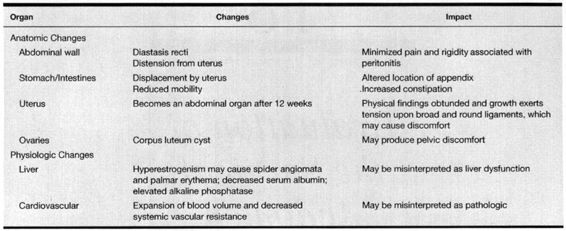

Later in pregnancy, physical findings are greatly distorted by alterations in the normal anatomic relationships that develop as the uterus and its contents grow. Classic physical signs of peritonitis, such as rebound tenderness and abdominal guarding expected in the nonpregnant patient with a surgical abdomen, may not be reliably elicited during pregnancy, presumably due to laxity of the abdominal muscles and stretching of the peritoneum. Similarly, failure to consider the normal physiologic adaptations of pregnancy may cause erroneous interpretation of laboratory test results. The more common anatomic and physiologic changes that must be considered in the evaluation of a gravid woman with a possible surgical abdomen are listed in Table 18-1.

TABLE 18-1. Examples of Anatomic and Physiologic Changes of Pregnancy that Could Alter the Evaluation of the Surgical Abdomen

DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES

The limitations of the diagnostic techniques described in the following paragraphs must be realized along with the knowledge that their use during pregnancy for evaluation of many gastrointestinal disorders has not been completely validated. While none of these procedures should be considered routine during pregnancy, they likewise should not be withheld if indicated.

ENDOSCOPY

Confirming diagnosis of most gastrointestinal lesions cannot be made by physical examination alone. The advent of fiberoptic endoscopic instruments for examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract as well as the colon has revolutionized the diagnosis and management of many of gastrointestinal disorders. Endoscopy is particularly well suited for use in the pregnant woman.

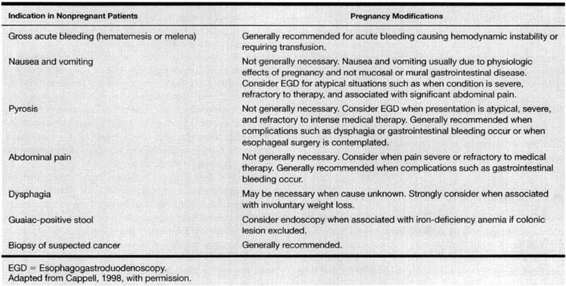

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy permits evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. With specialized instruments, the proximal jejunum can be studied, and the ampulla of Vater can be cannulated to perform retrograde cholangiopancreatography. In addition to its utility as a diagnostic technique, endoscopy may also be employed as a therapeutic modality in the management of many gastrointestinal disorders including bleeding. Cappell (1998) estimated that about 12,000 pregnant women each year have a potential indication for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (Table 18-2). The safety of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy during pregnancy was recently reviewed (Cappell, 1998). In a case-controlled investigation of 83 esophagogastroduodenoscopies during pregnancy, there were no maternal or neonatal complications related to the procedure (Cappell and colleagues, 1996a). The mean gestational age at the time of the procedure was 20 weeks, and gastrointestinal bleeding and pain accounted for over three-fourths of the indications.

TABLE 18-2. Potential Indications for Esophagogastroduodenoscopy During Pregnancy

Colonoscopy permits visualization of the entire colon and may be invaluable for the diagnosis and management of several gastrointestinal disorders including inflammatory bowel disease, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, and severe diarrhea. Cappell and colleagues (1996b) described experiences from 10 medical centers concerning the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of sigmoidoscopy during pregnancy. Of 48 flexible sigmoidoscopic examinations, 27 resulted in the identification of a lesion, 15 resulted in the initiation or adjustment of therapy for inflammatory bowel disease, 2 allowed avoidance of laparotomy, and 14 resulted in early hospital discharge. There were no maternal or fetal complications as a direct result of the procedure.

IONIZING RADIATION

The x-ray image is the most important image using ionizing radiation. X-rays are very short wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum that behave as bundles of energy called photons (Curry and colleagues, 1990). Ionization refers to the ability of x-rays to excite atoms by detaching electrons as the x-rays pass through a substance. There are several methods to measure the effect of x-rays. Standard terms used are the exposure in air, measured in Roentgens, the dose to tissue in rads, and the relative effective dose to tissue measured in rems. For diagnostic x-rays, the dose that is expressed in rad and the relative effective dose that is expressed in rem are the same, and these units can be used interchangeably. For the sake of consistency, all doses subsequently discussed are expressed in traditional units of rad or rem instead of their modern units Gray (Gy) or Sievert (Sv).

DOSIMETRY

Dosimetry refers to the calculated average dose from ionizing radiation associated with a particular study. The dose is calculated based on many factors including the type of study, type of equipment, distance of organ in question from the source of radiation, thickness of the body part penetrated, and individual methods of the radiologist performing the study (Wagner and associates, 1997). Because of tremendous variability of these factors, assignment of an average dose can be imprecise (Taylor and coworkers, 1979).

FETAL RISK OF IONIZING RADIATION

The harmful effects of ionizing radiation can be direct or indirect with three principal biologic effects: (a) cell killing, which affects embryogenesis; (b) carcinogenesis secondary to mutation activation of an oncogene; and (c) genetic effects secondary to mutation in a germ cell (Brent, 1989; Hall, 1991). Harmful fetal effects of ionizing radiation have been studied extensively in the case of cell damage with resultant dysfunction of embryogenesis both in the animal model and in human studies of Japanese atomic bomb survivors (Committee on Biological Effects, 1990; Gaulden and Murry, 1980). At 15–18 weeks, the embryo is most susceptible to radiation-induced mental retardation. This risk is probably a nonthreshold linear function of dose with the following incidence of severe mental retardation: 4 percent at 10 rad; 20 percent at 50 rad; 40 percent at 100 rad; and 60 percent at 150 rad (Committee on Biological Effects, 1990; Hall, 1991).

The official view of the American College of Radiology is that no single diagnostic procedure results in a radiation dose that threatens the well being of the developing embryo or fetus (Hall, 1991). Cumulative doses from multiple procedures, however, may enter that harmful range, especially at 8—15 weeks’ gestation. At 16–25 weeks, the risk is less, and there is no proven risk in humans below 8 weeks or greater than 25 weeks’ gestation (Committee on Biological Effects, 1990).

PLAIN X-RAY FILMS

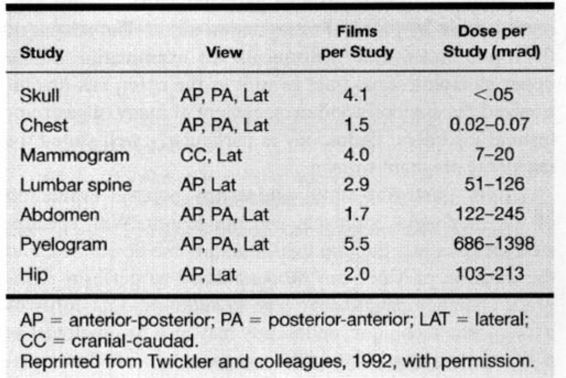

To put the fetal risk into perspective, it is important to consider the dosimetry of x-ray procedures, realizing that the average is a crude estimate. Table 18-3 lists the dose for some commonly used standard plain film x-rays.

TABLE 18-3. Dose to the Uterus for Common Diagnostic Radiologic Procedures

FLUOROSCOPY AND ANGIOGRAPHY

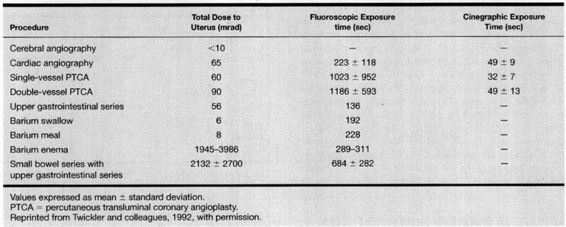

Assignment of dosimetry for fluoroscopic and angiographic procedures is much more difficult because of variations in the number of x-ray films obtained, fluoroscopy time, and the percentage of fluoroscopy time the fetus is in the radiation field. Some of these values are given in Table 18-4; their range is quite variable.

TABLE 18-4. Representative Doses to Uterus/Embryo from Common Fluoroscopic Procedures

COMPUTED AXIAL TOMOGRAPHY

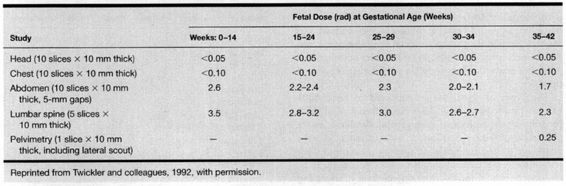

Computed tomography, an important imaging technique for evaluation of most organ systems, involves multiple exposures of very thin x-ray beams in a 360°-circle with computerized interpretations of these exposures. The result is an axial (and occasionally sagittal) image of a portion of the body, referred to as a slice. Multiple slices of the targeted body part are obtained along the length of the entire organ or of the area in question. For example, routine cranial tomography is performed with 10–15 slices, each 10 mm thick, to show the entire brain in an axial projection. Many variables in a given tomographic study will affect the calculations of radiation doses, especially the thickness and number of slices obtained. If a study is performed with and without contrast, twice as many images are obtained over the target area; therefore, the dose to that area is doubled.

Newer-generation tomographic equipment is more sensitive and flexible than are older systems. When compared with less-directed x-ray equipment, however, there is less exposure from scatter, thus areas not directly scanned have less risk of radiation exposure. All of this information is compiled in Table 18-5, which provides dosimetry calculations for various tomographic studies. The low dose from cranial tomography is the result of the distance of the fetus from the maternal head. As the target scanned is closer to the fetus—for example, the chest—there is more exposure. When the fetus is within the area scanned—for example, the pelvis—exposure is greatest.

TABLE 18-5. Estimated Maximum Fetal Doses from Computed Tomographic Scans

Spiral CT is a recent technical advancement that has essentially replaced conventional CT because it permits faster acquisition of axial images with the potential for better resolution. The radiation dose is similar to conventional computed tomography but is dependent upon pitch, which determines the quantity of tissue exposed (Wagner and colleagues, 1997): the higher the resolution, the lower the pitch, and the higher the exposure. For the most common indications in obstetrics—head imaging and pelvimetry—the exposure to the fetus from spiral CT is similar to conventional CT.

ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound is perhaps the most important adjunct to the physical and laboratory evaluation of the surgical abdomen. It often permits rapid and confident diagnosis of several abdominopelvic disorders. The safety record of diagnostic ultrasound is exemplary. However, Miller and associates (1998) emphasize that this record has been primarily established on the basis of experience with devices whose outputs are relatively low as compared with what is currently available. Indeed, since 1992, the Federal Drug Administration has permitted higher power outputs but has also required the display of mechanical and thermal indices that indicate the potential for ultrasound-induced tissue cavitation and heating. Miller and associates (1998) recently reviewed the subject of potential mechanical and thermal injury resulting from diagnostic ultrasound and concluded that clinicians should be prudent in the use of diagnostic ultrasonography by using the lowest signal output level and the shortest examination duration to obtain the diagnostic information.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging is invaluable for evaluating the abdomen and retroperitoneal space during pregnancy. Rather than ionizing radiation, magnetic resonance employs powerful magnets to temporarily alter the energy state of hydrogen protons in molecules, especially water. Through a series of acquisitions, information about the location and characteristics of these hydrogen protons can be obtained as they return to their normal state (Curry and associates, 1990). These acquisitions are computerized to produce an image.

Several investigations have been directed to the safety of magnetic resonance imaging. To date, there are no reported harmful effects of its use in pregnancy, including mutagenic effects (Forstner and colleagues, 1996; Geard and colleagues, 1984; Schwartz and Crooks, 1982). No deleterious effects have been reported in diagnostic systems that use less than 2 tesla (a measure of magnetic field strength). Nonetheless, the National Radiological Protection Board advises against imaging in the first trimester unless termination of pregnancy is probable (Garden and coworkers, 1991).

In a number of studies, magnetic resonance imaging was used in the management of maternal complications of pregnancy and estimation of fetal weight (Angtuaco, 1992; McCarthy, 1985; Weinreb, 1985, 1986; Uotila, 2000; and their coworkers). Forstner and colleagues (1996) reviewed the subject. As discussed in Chapter 17, magnetic resonance imaging may be useful for evaluation of suspected venous thrombosis.

EFFECT OF SURGERY AND ANESTHESIA ON PREGNANCY OUTCOME

If complications of surgical disorders per se are considered, there is little evidence to suggest that an otherwise technically uncomplicated surgical and anesthetic procedure will increase adverse pregnancy outcome. For example, complications from perforative appendicitis with gross peritonitis are associated with increased maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, even if surgical procedures and anesthetic management are flawless. Contrariwise, if these procedures themselves have complications, then these can adversely affect pregnancy outcome. For example, if the woman who undergoes uncomplicated surgery for appendicitis suffers vomiting with aspiration of acidic gastric contents, then resulting respiratory failure may cause fetal death, preterm labor, or both, as well as significant maternal morbidity and even mortality.

Mazze and Källén (1989) studied the effects of 5405 nonobstetric surgical procedures performed in 720,000 pregnant Swedish women from 1973 to 1981. Surgery was performed most commonly in the first trimester—41 percent as compared with 35 percent in the middle trimester and 24 percent in the third. Abdominal surgery comprised a fourth of all operations, and another 19 percent were accounted for by gynecologic and urologic procedures. Laparoscopic procedures were done in 16 percent of these women with the vast majority done in the first trimester. While laparoscopy was the most commonly performed first trimester operation, appendectomy was the most common procedure in the second trimester.

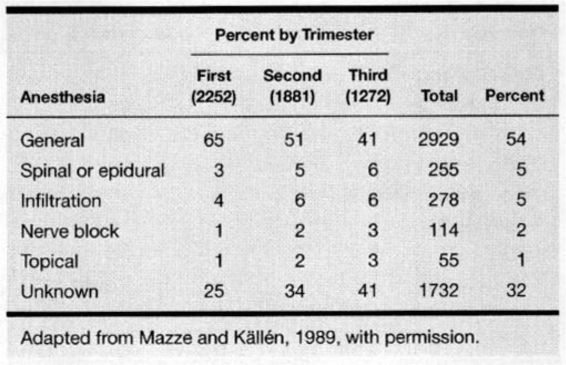

The types of anesthesia administered to these 5405 women are shown in Table 18-6. More than half of these procedures were performed using general anesthesia, and in 98 percent of these general anesthetics, nitrous oxide supplemented by another inhalation agent or intravenous medication was used. General anesthesia does not appear to be associated with an increased teratogenic risk (Czeizel and coworkers, 1998).

TABLE 18-6. Types of Anesthesia for Surgery in 5405 Pregnant Women

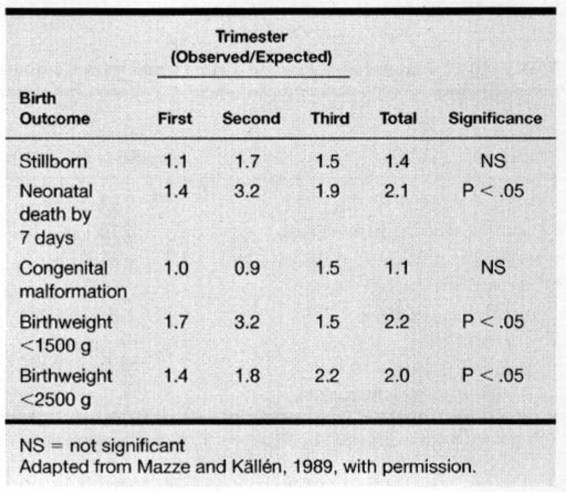

To determine any adverse effects of these diseases or their surgical and anesthetic managements on pregnancy outcome, the 5405 pregnancies in the Swedish report were compared with the total database of 720,000 pregnancies for the 9-year period. As shown in Table 18-7, there was a significant increase in incidence of low-birthweight and preterm infants, as well as in neonatal deaths by 7 days, in these women who had undergone surgery. Importantly, the stillbirth and congenital malformation rates were not increased significantly. From these data, these investigators concluded that nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy is not without hazard. They attributed excessive perinatal morbidity to the disease itself, rather than to adverse effects of surgery and anesthesia.

TABLE 18-7. Birth Outcomes in 5405 Pregnant Women Who Underwent Nonobstetric Surgery

Using an expanded version of the Swedish registry, Reedy and colleagues (1997) evaluated laparoscopy during pregnancy. A total of 2181 laparoscopies and 1522 laparotomies, performed prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, were identified from the registry, which consisted of over 2 million deliveries between 1973 and 1993. Although the authors again found that surgery (or the surgical condition) was associated with an increased incidence of low-birthweight and preterm delivery, they found no significant differences in these outcomes when laparoscopy was compared with laparotomy. Similarly, they found that congenital malformation and infant survival rates were similar with the two methods.

Kort and coworkers (1993) reviewed the outcomes of 78 nonobstetric operations performed during pregnancy over a 10-year period at hospitals affiliated with the University of North Carolina. The most common indications for surgical treatment were appendicitis, adnexal mass, and cholecystitis. They observed that the perinatal mortality rate was not increased in women undergoing nonobstetric operations. In addition, they found no measurable benefit from the use of perioperative prophylactic tocolysis.

PARENTERAL NUTRITION

For some of the gastrointestinal disorders that will be discussed, parenteral feeding or hyperalimentation may be considered. Its purpose is to provide nutrition when the gastrointestinal tract must be kept quiescent. Peripheral venous access may be adequate for short-term supplemental nutrition, which derives calories from isotonic fat solutions. Jugular or subclavian venous catheterization is necessary for total parenteral nutrition because its hyperosmolarity requires rapid dilution in a high-flow system. These solutions provide up to 24–40 kcal/kg, principally as hypertonic glucose solution; they frequently cause thrombophlebitis if infused by peripheral vein. Madan and colleagues (1992) reported that these hyperosmolar solutions might be infused through a peripheral vein with a low risk of thrombophlebitis if an ultrafine-bore silicone catheter is used. Greenspoon and associates (1993) described peripheral placement of a silicone catheter advanced into the superior vena cava. In three women, parenteral nutrition was carried out for 28–137 days without complications or the need to replace the catheter.

Kirby and colleagues (1988) reviewed the use of total parenteral nutrition for a variety of indications in 55 pregnant women. Gastrointestinal disorders were the most common indication, and the duration of parenteral feeding ranged from conception to delivery with a mean of 4.8 weeks. Complications were identified in about one-third of these women, and one that is particularly worrisome is the reversible Wernicke-Korsakoff psychosis, which may complicate up to 10 percent of cases. Lee and colleagues (1986) emphasize that parenteral nutrition for the woman with diabetic gastroenteropathy is particularly hazardous, and they reported one antepartum maternal death and four other women with deteriorating renal function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree