Chapter 637 Evaluation of the Patient

Immunofluorescence Studies

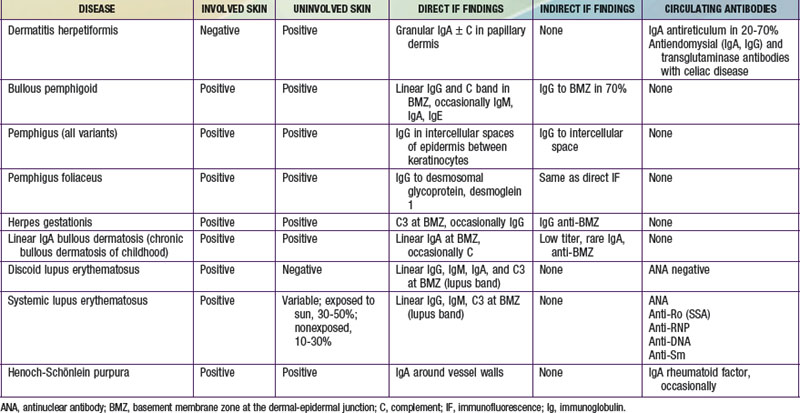

Immunofluorescence studies of skin can be used to detect tissue-fixed antibodies to skin components and complement; characteristic staining patterns are specific for certain skin disorders (Table 637-1). Serum can be used for identifying circulating antibodies. Skin biopsy specimens for direct immunofluorescence preparations should be obtained from involved sites except in those diseases for which perilesional skin or uninvolved skin is required. A punch biopsy sample is obtained, and the tissue is placed in a special transport medium or immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for transport or storage. Thin cryostat sections of the specimen are incubated with fluorescein-conjugated antibodies to the specific antigens.

637.1 Cutaneous Manifestations of Systemic Diseases

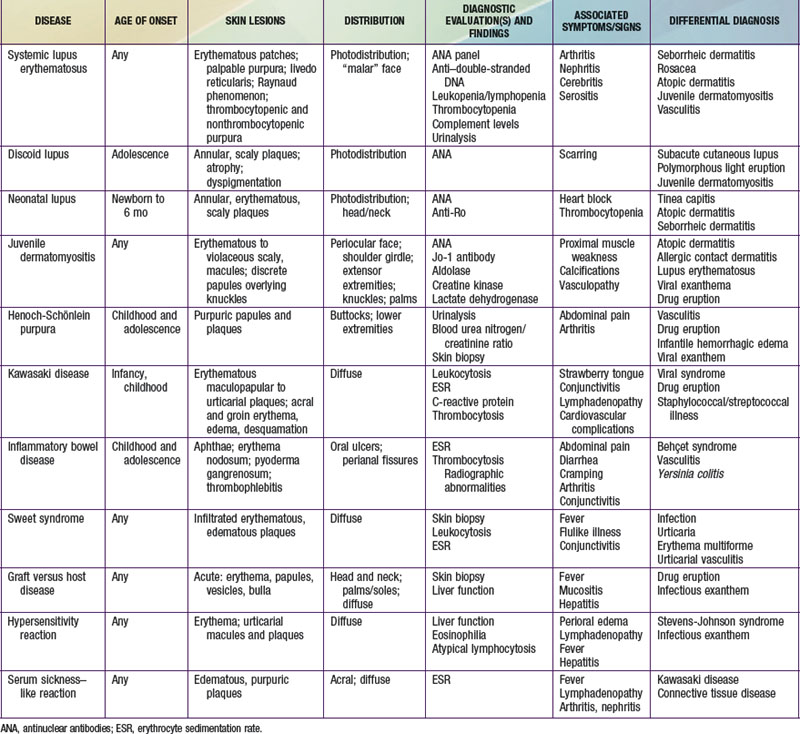

Selected diseases have signature skin findings, often as the presenting signs of illness, that can facilitate the assessment of patients with complex medical status (see Table 637-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Connective Tissue Diseases

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus (LE; Chapter 152) is an idiopathic autoimmune inflammatory disease that may be multisystemic or confined to the skin.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic LE (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease. It is a diagnosed when 4 of 11 well-defined criteria are present (Chapter 152). Three of the criteria are skin findings. Criterion 1 is the classic malar or “butterfly” rash (Fig. 637-1). It must be distinguished from other causes of a “red face,” most notably seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea. Criterion 2 is a discoid rash. Criterion 3 is a photosensitive erythematous macular or papular eruption (Fig. 637-2). Other associated but not diagnostic cutaneous findings include purpuric lesions, livedo reticularis, mucosal ulcerations, Raynaud phenomenon, and nonscarring alopecia.