Chapter 665 Evaluation of the Child

History

A comprehensive history should include details about the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods. Prenatal history should include maternal health issues: smoking, prenatal vitamins, illicit use of drugs or narcotics, alcohol consumption, diabetes, rubella, and sexually transmitted infections. The child’s prenatal and perinatal history should include information about the length of pregnancy, length of labor, type of labor (induced or spontaneous), presentation of fetus, evidence of any fetal distress at delivery, requirements of oxygen following the delivery, birth length and weight, Apgar score, muscle tone at birth, feeding history, and period of hospitalization. In older infants and young children, evaluation of developmental milestones for posture, locomotion, dexterity, social activities, and speech are important. Specific orthopedic questions should focus on joint, muscular, appendicular, or axial skeleton complaints. Information regarding pain or other symptoms in any of these areas should be appropriately elicited (Table 665-1). The family history can give clues to heritable disorders. It also can forecast expectations of the child’s future development and allow appropriate interventions as necessary.

Table 665-1 CHARACTERIZATION OF PAIN AND PRESENTING SYMPTOM

Physical Examination

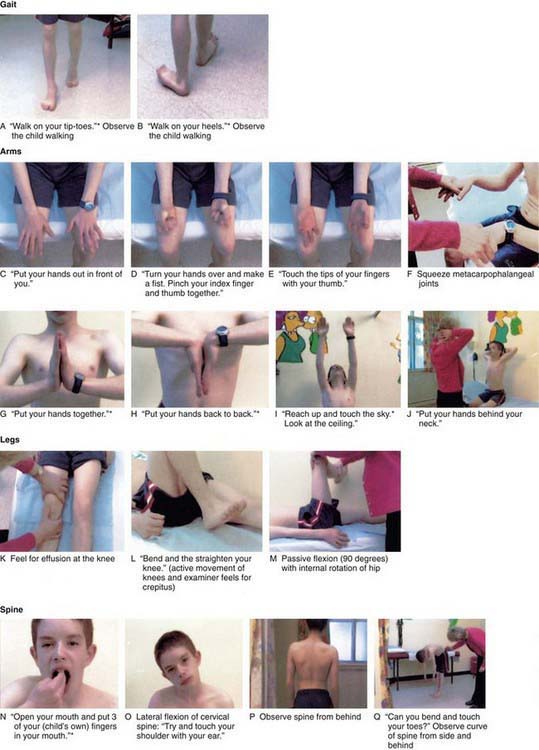

The orthopedic physical examination includes a thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system along with a comprehensive neurologic examination. The musculoskeletal examination includes inspection, palpation, and evaluation of motion, stability, and gait. A basic neurologic examination includes sensory examination, motor function, and reflexes. The orthopedic physical examination requires basic knowledge of anatomy of joint range of motion, alignment, and stability. Many common musculoskeletal disorders can be diagnosed by the history and physical examination alone. One screening tool that has been useful in adults has now been adapted and evaluated for use in children, the pediatric gait, arms, legs, spine (pGALS) test, the components of which are listed in Figure 665-1.

Inspection

Initial examination of the child begins with inspection. The clinician should use the guidelines listed in Table 665-2 during inspection.

Table 665-2 GUIDELINES DURING INSPECTION OF A CHILD WITH MUSCULOSKELETAL PROBLEM