Chapter 192 Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli are important causes of enteric infections as well as urinary tract infections (Chapter 532), sepsis and meningitis in the newborn (Chapter 103), and bacteremia and sepsis in immunocompromised patients (Chapter 171) and in patients with intravascular devices (Chapter 172).

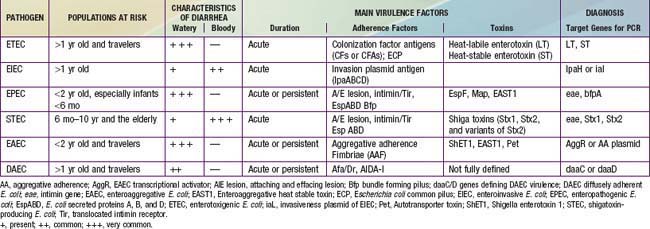

Because E. coli are normal fecal flora, pathogenicity is defined by demonstration of virulence characteristics and association of those traits with illness (Table 192-1). The mechanism by which E. coli produces diarrhea typically involves adherence of organisms to a glycoprotein or glycolipid receptor, followed by production of some noxious substance that injures or disturbs the function of intestinal cells. The genes for virulence properties and for antibiotic resistance are often carried on transferable plasmids, pathogenicity islands, or bacteriophages. In the developing world, the various diarrheagenic E. coli cause frequent infections in the first few years of life. They occur with increased frequency during the warm months in temperate climates and during rainy season months in tropical climates. Most diarrheagenic E. coli strains (except STEC) require a large inoculum of organisms to induce disease. Infection is most likely when food-handling or sewage-disposal practices are suboptimal. The diarrheagenic E. coli are also important in North America and Europe, although their epidemiology is less well defined in these areas than in the developing world. Recent data in North America suggest that the various diarrheagenic E. coli could be the etiology of as much as 30% of infectious diarrhea in children <5 yr of age.