Episiotomy

The precise origin of the episiotomy is difficult to determine; however, one of the first to describe it was a Dublin midwife, Sir Fielding Ould. As early as 1742, in his Treatise of Midwifery in Three Parts, he recommended the procedure for some cases in which the external vaginal opening was so tight that labor was dangerously prolonged (Ould, 1742). The first report of episiotomy in the United States is attributed to Taliaferro of Virginia. Almost 110 years after Ould’s Treatise, in a journal entitled The Stethoscope and Virginia Medical Gazette, Taliaferro (1852) published an account of a delivery of a 16-year-old eclamptic woman. After 18 hours of labor and at least a quart of bloodletting, her perineum was sufficiently distended to deliver the infant. Thinking a tear of the rectum was imminent, Taliaferro used a scalpel to cut a 1-inch left mediolateral episiotomy to facilitate delivery. The infant was stillborn, but the convulsions ceased postpartum, and the woman regained consciousness the following evening. Taliaferro wrote, “When this was undertaken by me, I was not aware of its having been done before, and was really afraid that my professional brethren would condemn me.”

Indications for using the episiotomy were greatly expanded in the United States when two prominent obstetricians, Pomeroy and DeLee, became champions of the procedure. In The Prophylactic Forceps Operation, DeLee (1920) claimed the episiotomy would preserve the integrity of the pelvic floor and introitus, forestall uterine prolapse and rupture of the vesicovaginal septum, and restore virginal conditions. Further, episiotomy combined with forceps delivery would save the fetal brain from injury, reduce the amount of epilepsy and mental retardation, and prevent anoxia. DeLee recommended a forceps delivery with a mediolateral episiotomy for all nulliparas.

In addition to the strong advocacy of episiotomy by the most notable obstetricians of the day, changing practices surrounding the birthing process also contributed to the increasing use of this procedure. In 1900, less than 5 percent of the women in the United States delivered in hospitals; by 1930, about 25 percent delivered in hospitals; and by 1950, more than 80 percent delivered in hospitals (Thacker and Banta, 1983). The shift to in-hospital deliveries, while no doubt in large part responsible for improvements in maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, also was closely associated with the increased frequency with which episiotomies were performed.

In the United States in the early 1920s and 1930s women frequently were given “twilight sleep,” a powerful combination of drugs that rendered the laboring woman oblivious. Her inability to cooperate actively in the birth process increased the use of forceps, which required extra room for vaginal manipulations. With the move into the hospital, the most common place for giving birth became the delivery room table, and lithotomy became the most common position, one believed by many to often unnecessarily place additional stress on the perineal body and lead to tears whether or not an episiotomy is cut (Bromberg, 1986; Thompson, 1987; Yeomans, 1991).

During the back-to-nature movement of the 1970s the emphasis was on decreasing interventions during parturition. Opposition to routine episiotomy surfaced in both the United States and Britain (Arms, 1975; Haire, 1972; Kitzinger, 1981; Thacker and Banta, 1983). Two publications were particularly important in demanding a reassessment of routine episiotomy; the first was published by the National Childbirth Trust in London (Kitzinger, 1981) and the other, by the epidemiologists Thacker and Banta (1983) in the United States. These investigators concluded that the widespread use of episiotomy did not withstand scientific scrutiny; that the risk of episiotomy had been largely ignored; and that if women were fully informed of the risk/benefit ratio, they would be unlikely to consent readily to having a routine episiotomy performed.

INTERPRETATION OF DATA

INFLUENCE OF PRACTICE DIFFERENCES

In the United States, medical doctors perform the majority of deliveries, and when employed, the midline episiotomy is most often used (Gass, 1986; Shiono, 1990; Thorp, 1987; and their associates). In contrast, midwives perform the majority of deliveries in Great Britain (Harrison and colleagues, 1984; Reynolds and Yudkin, 1987), Belgium (Buekens and associates, 1985), Sweden (Larsson and coworkers, 1991; Rockner and collaborators, 1988, 1989; Rockner and Olund, 1991), and Denmark (Thranov and colleagues, 1990). Mediolateral episiotomy is performed almost entirely to the exclusion of midline episiotomies in Europe, as well as South Africa (Bex and Hofmeyr, 1987). In Canada, mediolateral episiotomies also are more commonly performed than in the United States (Walker and associates, 1991).

Thus, there are major differences in practice, which must be considered when evaluating the vast database available concerning episiotomies and their risks and benefits. For example, the complications of the midline episiotomy are largely limited to spontaneous extension involving injury to the anal sphincter and/or rectal mucosa. In the majority of midline episiotomies, a satisfactory repair is easily achieved; however, the incidence of rectovaginal fistulas and breakdown with cloaca formation is higher than with mediolateral episiotomies. On the other hand, mediolateral episiotomies are more often complicated by poor wound healing and long-term pelvic pain and dyspareunia.

To interpret the data correctly, one also must know the definition being employed for each degree of laceration. In Europe, episiotomies commonly are classified only as first-, second-, or third-degree, with the latter encompassing injuries to either the anal sphincter or rectal mucosa. The classification most often employed in the United States, and the one that we use is:

• First-degree laceration: Superficial laceration of the vaginal mucosa or perineal body not requiring suturing.

• Second-degree laceration or episiotomy: Involving the vaginal mucosa and/or perineal skin and deeper subcutaneous tissue and requiring suturing.

• Third-degree laceration or episiotomy: Extension of the laceration to involve any part of the capsule or anal sphincter muscle.

• Fourth-degree laceration or episiotomy: Extension to include involvement of the rectal mucosa.

INFLUENCE OF STUDY DESIGN

The majority of studies evaluating efficacy and complications of episiotomies are retrospective. In most of these studies, the indication confounders, that is, the indication for performing the episiotomy alone, also have been found to be indicators of risk for third-degree or fourth-degree tears. Studies based on observational data and not on randomized controlled trials can only provide limited evidence of benefits and hazards of the widespread use of episiotomy (Blondel and Kaminski, 1985). While these observational studies are perhaps a prerequisite to the design of pragmatic randomized trials, they are nonetheless poor substitutes, and it is surprising to find that there are only three prospective randomized trials that have attempted to determine the merits of the routine use of episiotomy (Harrison and associates, 1984; Sleep and colleagues, 1984; Argentine Episiotomy Trial Collaborative Group, 1993). Appropriately designed and randomized prospective trials are both time-consuming and costly. For instance, to test the hypothesis that the restricted use of episiotomy would double the incidence of damage to the anal sphincter or rectal mucosa from a rate of 0.6 percent with mediolateral episiotomies to a rate of 1.2 percent, would require a randomized controlled trial including 5000 women in each group (Blondel and Kaminski, 1985).

EPISIOTOMY RATES

Episiotomies are more often performed in nulliparous women, regardless of the background episiotomy rate (Sleep and associates, 1984, 1989). Harrison and coworkers (1984) reported the episiotomy rate in primigravidas delivered at the Rotunda Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, as 90 percent in the 6 months preceding a randomized trial, one arm of which entailed performing episiotomy only if essential. In the latter group, the episiotomy rate fell to 8 percent, with 20 percent delivering over an intact perineum and 25 percent sustaining only a first-degree tear. Although not reported until 1990, Shiono and colleagues reported a 62 percent episiotomy rate among women in the Collaborative Perinatal Project, which accumulated data from 1959 to 1966. McGuiness and colleagues (1991), reporting on a low-income inner-city population, found that almost half the women underwent episiotomy. This rate compares favorably to that reported by Olson and associates (1990) from a three-person family practice group in the rural United States. These physicians reported an overall episiotomy rate of 44 percent, 60 percent in nulliparas and 36 percent in multiparas. This rate is comparable to the 53 percent rate reported by Thranov and colleagues (1990) from Denmark. However, for all of Denmark, the episiotomy rate is 77 percent of nulliparas when cesarean section and instrumental delivery are excluded. Buekens and colleagues (1985) reported a 28 percent rate of episiotomies from 10 Belgium hospitals. The mean incidence of episiotomies in Sweden was 30 percent with a range in individual hospitals of 9 percent to 77 percent (Rockner and Olund, 1991). Among the lowest rates reported are those from Israel, where only 17 percent of women having their first child and 10 percent having a subsequent child have an episiotomy (Adoni and Anteby, 1991).

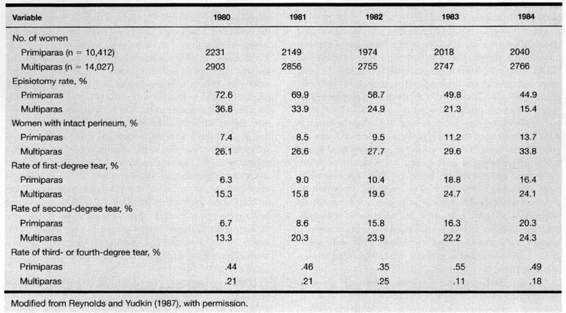

The trend observed at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, has been a steady decline in episiotomy rates for both nulliparous and multiparous women, with more intact perineal bodies and no increased significant perineal trauma. These trends, shown in Table 5-1, seem to reflect current trends in industrialized nations. The literature does not, however, readily allow direct comparison of identical or even similar time intervals worldwide. Although studies have evaluated damage that is visible at the time of vaginal birth, they have not evaluated the important, yet unexplored, problem of damage that occurs under the skin that may result in pelvic organ prolapse later on in life. As has been adequately demonstrated by studies on the anal sphincter (Sultan and colleagues, 1993), intact perineal skin does not always indicate intact pelvic support structures. Further information concerning these important injuries is needed before final conclusions can be made about episiotomy use and pelvic floor protection.

TABLE 5-1. Perineal Management During Labor Among 24,439 Women at John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, Between 1980 and 1984

INDICATIONS FOR EPISIOTOMIES

Affecting the final decision regarding the need for and relative merits of episiotomy are a host of factors, including training and clinical experience, as well as the individual woman’s desires. To illustrate this, Graham and colleagues (1990) asked providers in New Mexico if they performed episiotomies in more than three-fourths of their nulliparous patients. The “yes” answers were distributed along a continuum: 100 percent of obstetric residents, 80 percent of obstetricians, 65 percent of family practitioners, 25 percent of nurse midwives, and less than 5 percent of lay midwives. The rates for episiotomies in multiparous women were lower but distributed along the same continuum.

Most practitioners agree that episiotomy is justified in instances of perceived fetal or maternal distress. Episiotomy also is indicated, albeit on an intuitive basis, in operative vaginal deliveries requiring additional room to safely accomplish the delivery. Included in this category are delivery of the breech, multi fetal gestations, and persistent occiput posterior presentations. Low and midforceps deliveries also are accepted indications, as are vacuum extraction deliveries, which may be facilitated by an episiotomy. The woman should be educated that in most cases, the birth attendant must make a clinical decision for which the majority of the prerequisite information will not be available until the moment that birth is about to occur.

PERFORMANCE OF EPISIOTOMY

SUTURE MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES FOR REPAIR OF PERINEAL TRAUMA

The choice of suture materials, as well as technique for repair of perineal trauma, have been subjects of debate, but have remained largely the choice of the individual surgeon. Principal materials used for repairs include absorbable and nonabsorbable suture. Absorbable suture materials include chromic catgut, glycerol-impregnated catgut, polyglycolide (Dexon), and polygalactide (Vicryl). For transcutaneous suturing, the absorbables have virtually replaced the previously used nylon and silk sutures.

Grant (1989) reviewed 14 controlled trials that addressed choice of suture material and technique for repair of perineal trauma. The derivatives of polyglycolic acid—Dexon and Vicryl—were the absorbable materials of choice for both deep and skin closure. Compared to catgut, polyglycolic acid sutures were associated with about a 40 percent reduction in short-term pain and need for analgesia. Their early benefit, however, may be more than offset by the frequent need for removal of the polyglycolic acid sutures during the puerperium. Some authors indicate an increased need for removal of polyglycolic acid sutures 10 days after delivery (Mahomed and colleagues, 1989) but this runs counter to most clinicians’ experience. The principal drawback to chromic suture is the rapidity with which it loses tensile strength, accelerated even more by infection or inflammation, resulting in the occasional need to resuture perineal wounds closed with catgut (Banninger and colleagues, 1958; Livingstone and coworkers, 1954; Mahomed and associates, 1989).

Spencer and associates (1986) compared glycerol-impregnated chromic catgut with chromic catgut in a randomized comparison for the repair of childbirth perineal trauma. Glycerol-impregnated chromic catgut caused more pain than chromic catgut 10 days after delivery and it was found to be associated with significantly more dyspareunia both at 3 months and 3 years after delivery. The importance of what might seem such a mundane decision, that is, choice of suture material for episiotomy repair, was emphasized by Grant (1986), who estimated that in England and Wales alone, the choice of suture material for perineal repair could make a difference of as many as 30,000 new cases of dyspareunia per year. There is no role for glycerol-impregnated catgut in episiotomy repair.

When compared with nonabsorbable materials (both silk and nylon), polyglycolic acid skin sutures were associated with less short-term perineal pain. However, continuous, subcuticular stitches result in significantly less perineal pain than occurs with transcutaneous sutures. Additionally, there seldom is a need to remove subcuticular sutures postpartum, a common occurrence with polyglycolic acid-derivative sutures when used for transcutaneous closure. As an alternative, limited studies using a Histoacryl adhesive for coaption of skin edges with mediolateral episiotomies resulted in virtual abolition of need for postpartum analgesics or sitting aids and appeared far superior to the subcuticular suturing technique (Adoni and Anteby, 1991).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE FOR MEDIOLATERAL EPISIOTOMY

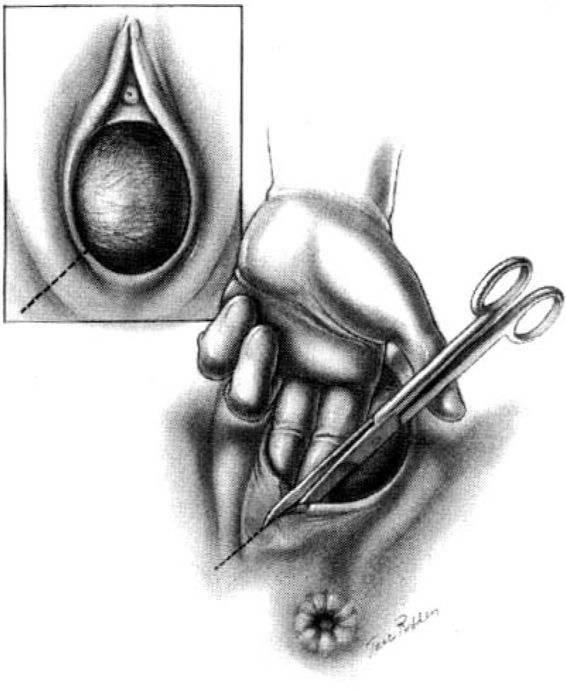

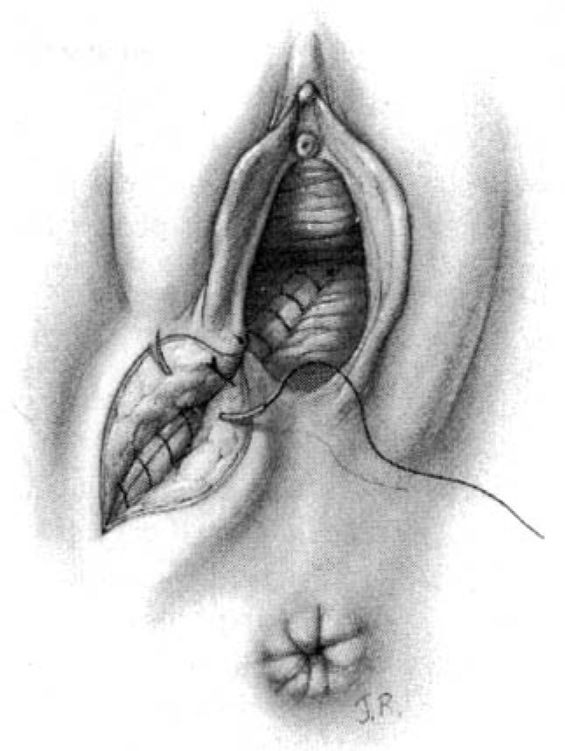

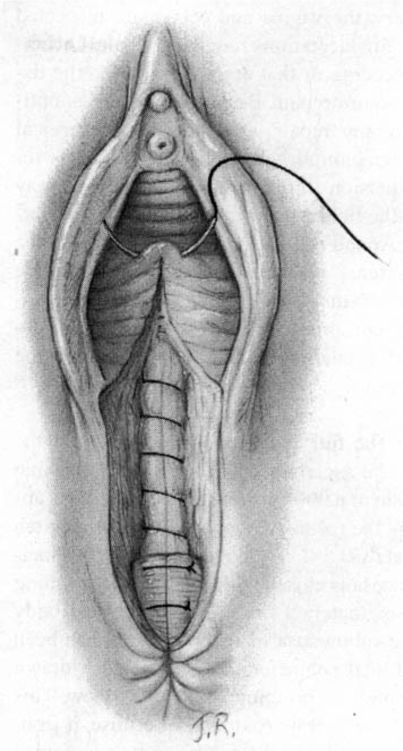

This surgical incision may be quite large, thus an adequate pudendal block or conduction analgesia is important. Under emergency conditions the procedure may be performed with local infiltration of an anesthetic agent. A scalpel or large, straight scissors are used. The procedure is performed when the perineum is bulging and when about 4 cm of fetal scalp is visible during a contraction. The incision is placed at 5 o’clock for a left mediolateral episiotomy. Regardless of the site, the incision is directed toward the ipsilateral ischial tuberosity. This incision must be made more horizontal than often thought in order to avoid sphincter injury. Those familiar with the appearance of the scar postpartum, which is approximately 45 degrees below the horizontal, must modify this angle at the time of episiotomy in order to achieve anal sphincter protection due to the change in tissue topography present when the head is distending the perineum. The operator’s two fingers in the vagina separate the labia and exert outward pressure on the perineum to flatten it slightly and to protect the presenting fetal part (Fig. 5-1). The incision must be deep enough to remove all perineal resistance to delivery of the infant and should extend at least 3-4 cm onto the perineum. Some clinicians feel that the fat in the ischiorectal fossa is commonly exposed when the episiotomy is of adequate depth (Willson, 1969).

FIGURE 5-1. The timing of performance of a right mediolateral episiotomy when approximately 3-4 cm of the fetal head is seen distending the perineum during a uterine contraction. Care should be taken that the incision is at 5 or 7 o’clock in order to avoid extension into the rectal sphincter muscle.

If the episiotomy is placed too far laterally, it will not provide the desired relaxation of the median portion of the levator plate. When the episiotomy is too small, it usually will not relieve the tensions on the perineal tissues; instead, it will provide a weak point from which may arise an associated extension in the form of an uncontrolled laceration. While an episiotomy can be enlarged with several successive cuts, this is not advisable because following the first incision, the wound edges become distorted by the pull of the muscles. Thereafter additional perineal cuts tend to produce a zigzag incision line.

SUTURE REPAIR. Prior to suture repair, the birth canal is exposed either manually or with suitable retractors. Retractors should be used cautiously because these instruments themselves may cause additional lacerations. Cervical or vaginal lacerations requiring suturing generally should be repaired prior to the episiotomy because exposure will be maximal if repairs are performed in this sequence. If necessary, either for removal of the placenta or because of atony and bleeding, manual exploration of the uterus should be performed prior to episiotomy closure if possible.

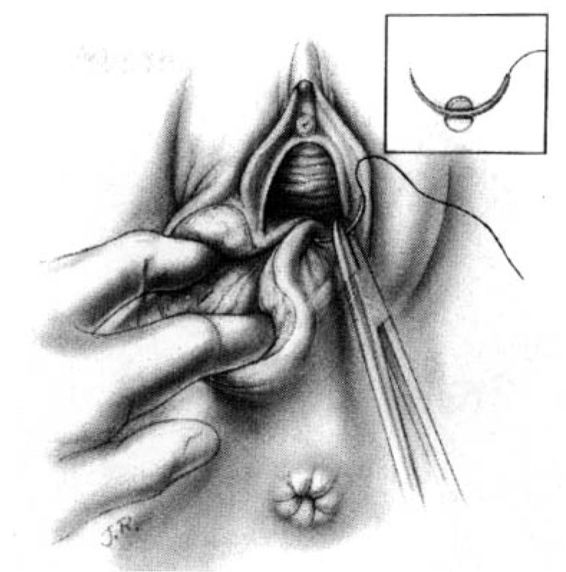

The surgeon places the second and third fingers of the left hand into the vagina to spread the vaginal and perineal wound margins. This provides access to the uppermost wound angle where suturing begins. Either 00 chromic on a taper CT1 needle or 00 synthetic absorbable suture on a taper CTX needle are suitable for repair. Placement of the anchor suture approximately 1 cm above the apex of the incision assists in hemostasis at the wound apex (Fig. 5-2). Each bite should include the supporting tissue between the vagina and the rectum as well as the vaginal mucosa to provide strong support. Sutures—either interrupted or continuous locking—of the vaginal mucosa are carried to the level of or slightly past the cut edges of the hymen to the introitus.

FIGURE 5-2. Repair of the mediolateral episiotomy. The operator is exposing the full extent of the episiotomy using the left hand. The first suture is placed at the vaginal apex approximately 1 cm cephalad to the most superior margin of the episiotomy or laceration. It is important to place the initial suture above the apex to ensure hemostasis of the repair. Insert shows correct position of the needle at the tip of the needle holder.

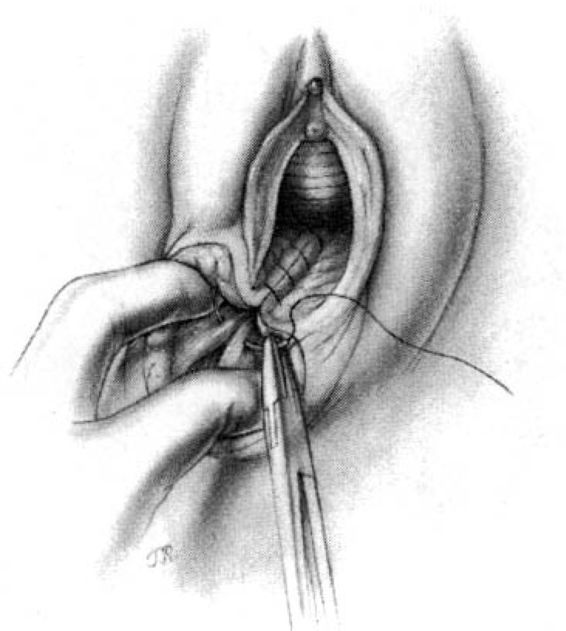

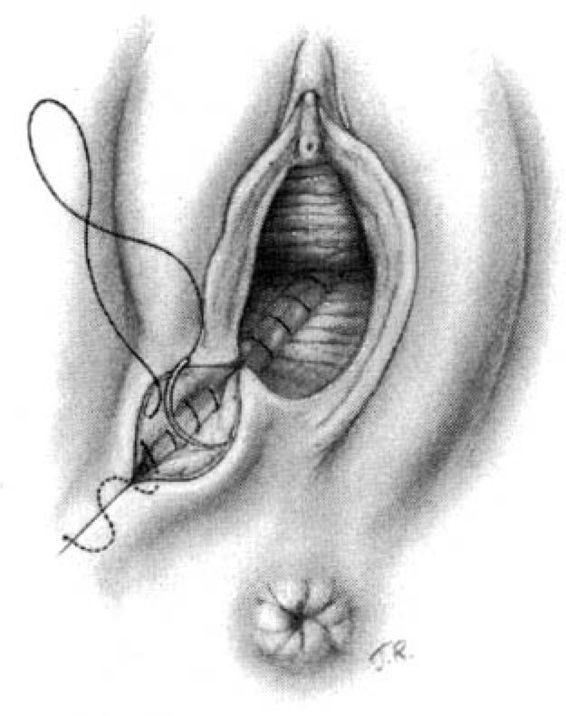

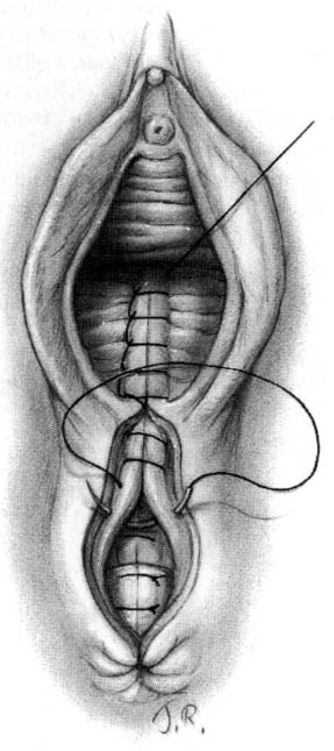

Attention is next directed toward the urogenital diaphragm, which is carefully reconstructed using deep interrupted sutures. During this portion of the repair, it must be remembered that the lateral tissues are located at a higher level than the corresponding median structures by virtue of the muscular distortion and retraction. Additionally, the fascia on the medial side usually retracts somewhat toward the midline and beneath the more superficial structures. Medially, the tissues lie close to the anterior rectal wall through which a suture can easily be placed inadvertently. The deep sutures should not be placed horizontally, but rather at a diagonal with the median side lower than the lateral (Fig. 5-3). In this way, comparable wound surfaces are united. To minimize discomfort and maximize healing, the operator should place the minimal number of sutures—usually between four and six—required to achieve adequate coaptation of the tissues and hemostasis. Repair of this portion of the episiotomy is more difficult for the novice and may demand additional time to achieve correct coaptation of the tissue surfaces. Failure to achieve correct coaptation of tissue will result in the reconstruction of the pelvic floor being anatomically incorrect. In addition healing and the aesthetic results will be poor.

FIGURE 5-3. Repair of the mediolateral episiotomy. The vaginal mucosa has been approximated not quite to the posterior commissure. The surgeon spreads the perineum widely and unites the deep perineal tissues in order to avoid leaving dead space. Medially, relatively little tissue is taken on the needle for suturing so as to ensure that the rectum will not be punctured. The wound surfaces are not reapproximated in a horizontal plane, but rather at an angle with lower medial tissues joined to higher lateral tissues.

The cut ends of the bulbocavernous muscle are approximated as the first step in closing the superficial layer of tissue. Because the muscle ends tend to retract upward, the skin edges must be pulled laterally and superiorly to facilitate visualization, and a deep bite is required to incorporate the necessary structures. This is an important stitch; unless the tissues are properly approximated, the introitus will gape.

Subcutaneous sutures usually will be required to reapproximate the subcutaneous fatty tissue (Fig. 5-4). Again, it is important to suture at a diagonal with the lateral side higher than the medial. The repair is completed by placement of either interrupted transcutaneous sutures through the perineal body or, preferably, a subcuticular closure using 000 suture of choice of the surgeon (Fig. 5-5).

FIGURE 5-4. Repair of the mediolateral episiotomy. The vaginal wound is sutured to the approximate level of the posterior commissure. The deep perineal tissues are joined together by means of interrupted sutures. The operator unites the perineal tissues with additional sutures, again taking care that the sutures join lower medial tissues to higher lateral structures.

FIGURE 5-5. Repair of the mediolateral episiotomy. The perineal skin edges are approximated using a subcuticular stitch of reabsorbable suture.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE FOR MIDLINE EPISIOTOMY

The midline episiotomy is the preferred procedure in the United States largely because of the ease of repair and the reduced pain during healing. As emphasized previously, when making the incision, the operator should take care to protect the presenting fetal part by placing at least two fingers between the presenting part and the episiotomy site. Adequate pain control may be achieved with conduction analgesia, pudendal block, or local tissue infiltration with an anesthetic agent. The perineum is incised from the midline of the posterior fourchette toward the anus. Either scissors or scalpel may be used for the incision. The position of the anal sphincter is easily ascertained by visualization and palpation and the episiotomy will be cut while attempting to avoid direct injury to the anal sphincter or rectal mucosa. Even when the anal sphincter or rectal mucosa have not been cut as a part of the episiotomy, up to one-fourth of midline episiotomies will extend to involve these structures. Because the midline episiotomy often involves tears of the anal sphincter muscle and/or rectal mucosa, the repair is described sequentially as a fourth-degree repair.

Following delivery, the vagina and cervix are inspected for the presence of any lacerations requiring repair. Lacerations that are not bleeding or that are not deep into the tissues rarely require suture repair. Because exposure is optimal prior to episiotomy repair, any sidewall or cervical lacerations should be sutured before the episiotomy is repaired. Because extension through the rectal mucosa may have contaminated the field with fecal material, it is important to irrigate the wound with copious amounts of fluids. Normal saline, mixtures of normal saline and povidone iodine solution, or mixtures of normal saline and hexachlorophene are all appropriate for irrigation; the choice depends largely upon availability and whether or not the woman has any allergies.

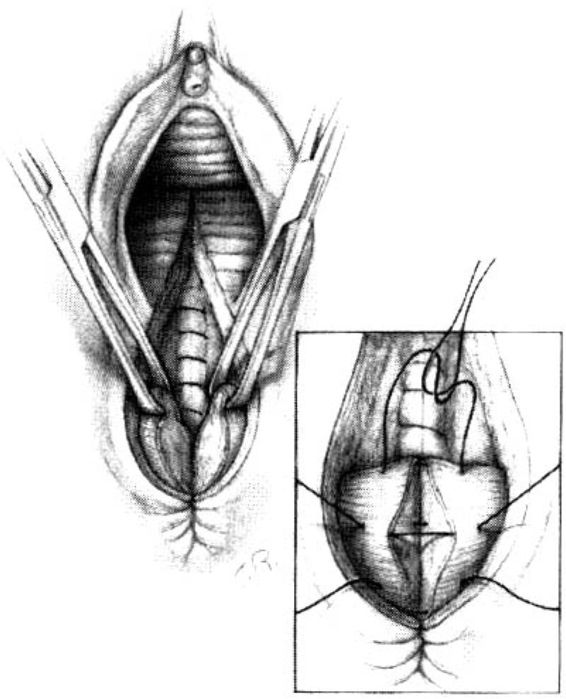

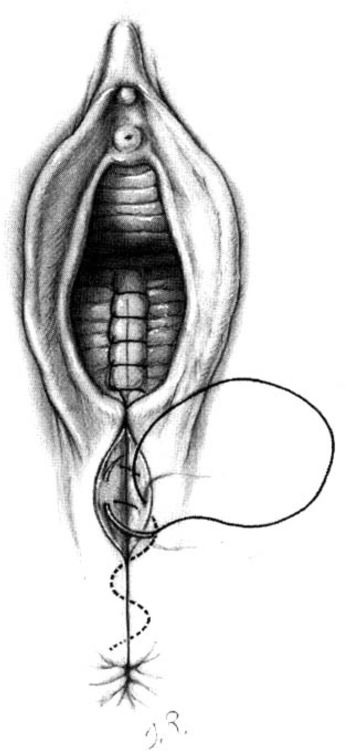

SUTURE REPAIR. The full extent of the laceration of the rectal mucosa must be ascertained. Either a 0000 chromic on a taper SH1 needle or a 000 chromic on a T5 needle is appropriate for closing the rectal submucosa. An anchor stitch is placed approximately 0.5-1 cm above the apex of the incision, and the submucosa is closed with a continuous running suture carried approximately 1 cm onto the perineal body (Fig. 5-6). After the submucosa of the anorectum has been closed, the internal anal sphincter has usually been drawn closer towards the midline bringing it closer to view. This layer must be accurately reapproximated because it contributes 75 percent of resting anal tone. It can be recognized by its white rubbery character and has often previously been identified as “fascia.” It lies between the external anal sphincter and the anal canal and should be repaired with running or interrupted suture of 000 synthetic absorbable material.

FIGURE 5-6. Repair of the midline episiotomy. The anchor stitch for closure of the rectal mucosa is placed 0.5-1 cm above the apex of the laceration. The rectal mucosa is then closed using either interrupted or running submucosal sutures of 000 or 0000 chromic or polyglycolic acid derivatives. Exposure can usually adequately be provided without assistance by use of the second and third finger of the operator’s nondominant hand placed into the vagina and widely spread to provide exposure of the wound.

The cut ends of the anal sphincter next must be identified. These muscular structures usually will have retracted laterally and are best visualized when grasped with an Allis clamp incorporating both the muscle and its capsule. The anal sphincter is closed with sutures incorporating both the fascial sheath and small amounts of muscle (Fig. 5-7). Some prefer to use 00 synthetic absorbable suture on a taper needle because the polygalactic acid maintains its tensile strength longer than chromic, and thus allows a longer period for healing. It is important to emphasize that the strength of this closure is obtained by incorporating fascia and not muscle. The fascial sheath is easier to close if the posterior capsule (commencing at 6 o’clock) is the first suture placed. The most cephalad stitch is placed next, at the 9 o’clock position of the left half of the sphincter capsule as viewed on cut end. The remainder of the capsule is closed with two or three interrupted stitches, the sequence of which is less important because visualization for these latter stitches is usually easy. It is important that approximately 1 cm of the sphincter capsule should be incorporated on each side and that the suture should be tied snugly but not so tight as to strangulate the tissue. Most caution against the use of a figure-of-eight stitch because it tends to bundle and strangulate tissue.

FIGURE 5-7. Repair of the midline episiotomy. Successful closure of the external anal sphincter depends upon reapproximation of the capsule of the sphincter muscle. Approximately 1 cm of capsule should be grasped on each side with closure by interrupted sutures. Avoid figure-of-eight sutures because they may lead to strangulation and compromise the blood supply during the healing phase.

It has been suggested that an overlapping technique may be superior to an end-to-end anastomosis (Sultan and associates, 1999). This strategy arose from studies of interval repair where an overlapping technique resulted in a higher rate of intact suture lines on subsequent endosonography. At the present time, most of the data relates to mediolateral episiotomies, and a sphincter tear in association with this incision is quite different than a tear in association with a midline episiotomy. In a recent randomized clinical trial comparing an overlap technique with an approximation for the primary repair of third-degree lacerations, Fitzpatrick and colleagues (2000) reported the outcome was similar with both techniques. There were no significant differences in median incontinence scores, fecal urgency, anal manometry results, or endoanal sonographic results. This study confirmed these authors’ previous work (Fitzpatrick and associates, 2000).

Next, the depth of the episiotomy is judged by placing two fingers of the left hand into the vagina and visualizing the apex of the episiotomy as the edges are pushed laterally. At this stage, three or four interrupted chromic or synthetic absorbable suture stitches are placed to reunite the separated margins of the perineal body (Fig. 5-8).

FIGURE 5-8. Repair of the midline episiotomy. A second layered closure is placed over the rectal mucosa by incorporating the internal anal sphincter. Care is again exercised to avoid passing the needle and suture material into the lumen of the bowel. This illustration depicts closing the internal anal sphincter after the external sphincter is closed, but it may be preferable to close the internal sphincter before uniting the external anal sphincter sutures.

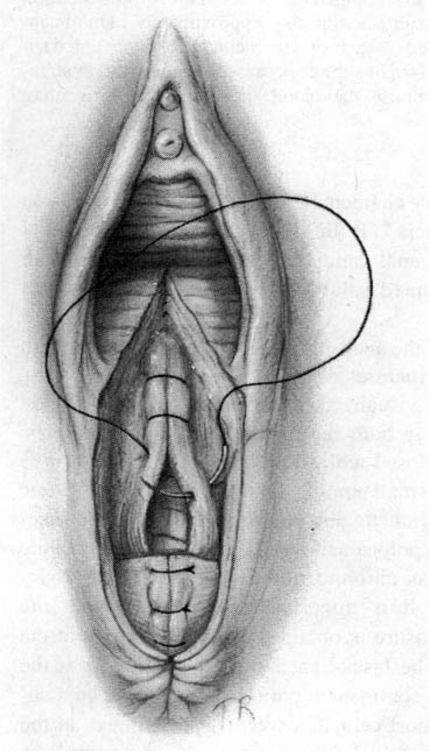

The remainder of the episiotomy closure is simply that of a second-degree repair. Visualizing the apex of the incision into the vaginal mucosa, an anchor stitch is placed approximately 1 cm cephalad (Fig. 5-9). The vaginal mucosa then is closed with a running or run-lock 000 synthetic absorbable suture carried to the level of the hymenal ring. The final vaginal stitch may be either tied at this point or directed from inside the vagina out onto the perineal body in the midline (Fig. 5-10). At this point, the depth of the defect on the perineal body must be assessed to determine whether closure can be adequately achieved in one layer or whether deep interrupted sutures will result in a superior closure. Where the cavity depth exceeds 1-1.5 cm, we prefer to place deep interrupted sutures in order to restore the perineum to its predelivery state. The deepest muscle layer that may have been incised or separated is the pubococcygeus. Two or three interrupted stitches usually will close this space.

FIGURE 5-9. Repair of the midline episiotomy. Similar to the principle applied to the mediolateral episiotomy, an anchor stitch is placed approximately 1 cm beyond the most superior extent of the episiotomy. This is an important stitch to ensure that cut or bleeding vessels are not missed at the apex of the wound.

FIGURE 5-10. Repair of the midline episiotomy. The technique of using one suture for closure of the midline episiotomy is demonstrated. After the vaginal mucosa has been reapproximated to the hymenal ring, the needle is passed from the midline of the vagina out onto the perineal body. The same suture can now be used for placement of the crown stitch.

Attention next is directed to reapproximation of the bulbocavernosus muscles and the labia. This stitch is important to restore perineal anatomy. Reapproximation may be accomplished by interrupted sutures, the beginning of a new suture that will be used for a continuous closure, or a continuation of the suture used for the vaginal mucosa. Attention should be directed toward ensuring that the reapproximation does not overly restrict the introitus and lead to dyspareunia. Following placement of this stitch, a continuous running suture is used to close the subcutaneous fat and the transverse perineal muscles. This stitch is carried to the inferior extension of the episiotomy on the perineal body, or to the end of the rectal mucosal closure, if one has been performed. At this point, a subcuticular suture is used to reapproximate skin edges (Fig. 5-11). At the apex the suture can again be directed from the midline into the vagina, following which the stitch can be placed through both sides of the vaginal mucosa and tied upon itself. The tissues should be snugly reapproximated, but not strangulated by undue tension. Such tension is certain to increase episiotomy site swelling and subsequent discomfort.

FIGURE 5-11. Repair of the midline episiotomy. The repair is completed by use of a subcuticular suture carried out from the inferior margin of the episiotomy upwards toward the hymenal ring. The suture is passed back into the vagina, where it is tied upon itself as opposed to leaving a knot on the perineal body.

POSTPARTUM PAIN RELIEF

Assuring postpartum comfort entails both local wound care and analgesics. Local measures begin immediately postdelivery, and include such simple maneuvers as applying perineal ice packs. Efforts should be made to keep the perineal body and any injury sites clean and dry. Twenty-minute sitz baths performed two or three times daily are soothing and help to keep the site clean. A spray bottle used after each voiding is helpful. Women should be instructed to blot the area dry. Hair dryers can also be used to keep the area dry.

A number of analgesic agents have been evaluated for postpartum pain treatment. Schachtel and colleagues (1989) demonstrated that ibuprofen (400 mg) and acetaminophen (1000 mg) were effective for postpartum pain relief as compared with placebo. Ibuprofen was more effective than acetaminophen. Hopkinson (1980) evaluated single-dose

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree