Chapter 706 Envenomations

General Approach to the Envenomated Child

Snake Bites

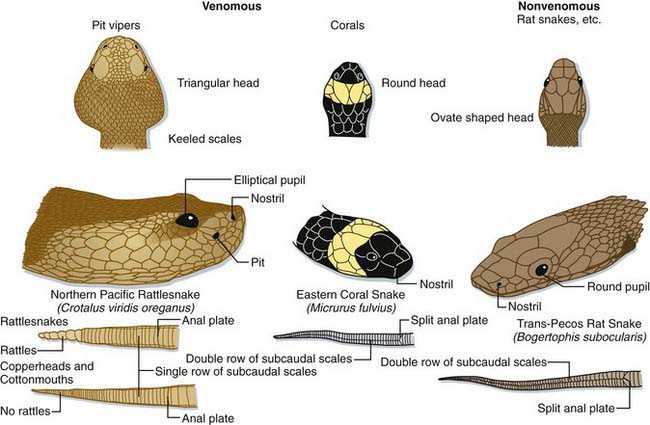

Most snake bites are inflicted by nonvenomous species and are of no more consequence than a potentially contaminated puncture wound (Fig. 706-1). Venomous snakes, however, kill many tens of thousands of people in the world each year. The precise number is difficult to ascertain, because the toll in human suffering is far greatest in developing nations. Developed nations, with established medical care systems, have relatively few fatalities each year.

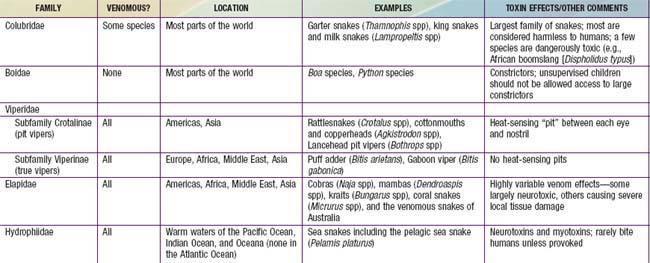

Most of the world’s medically significant venomous snakes belong to one of two families—Viperidae and Elapidae (Table 706-1). In developing nations, most snake envenomations occur in agricultural workers who inadvertently contact snakes while in the fields. Many victims of snake envenomation in developed nations are adolescent or young adult males, frequently intoxicated, who are attempting to handle or catch the snake. Bites are located on an extremity in over 95% of cases. In the USA, approximately 98% of venomous snake bites are inflicted by pit vipers (family Viperidae; subfamily Crotalinae). A small fraction of bites are caused by coral snakes (family Elapidae) in the South and Southwest, and by exotic snakes that have been imported.

Venoms and Effects

Snake venoms are complex mixtures of proteins including large enzymes that cause local tissue destruction and low molecular weight polypeptides that have the more lethal systemic effects. The symptoms and severity of an envenomation vary according to the type of snake, the amount of venom injected, and the location of the bite. The fear caused by a snake bite can result in nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cold/clammy skin, and even syncope regardless of whether or not venom was injected. In general, viper venoms can have deleterious effects on almost any organ system. Most viper bites cause significant local pain, swelling, ecchymosis, and variable necrosis of the bitten extremity (Fig. 706-2). The pain and swelling typically begin quickly after the bite and progress over hours to days. Serious envenomations may result in a consumptive coagulopathy, hypotension, and respiratory distress. In contrast, venoms from the Elapidae tend to be more neurotoxic with little or no local tissue damage. These bites cause variable local pain and the onset of systemic effects can be delayed for hours. Manifestations of neurotoxicity generally begin with cranial nerve palsies such as ptosis, dysarthria, and dysphagia and may progress to respiratory failure and complete paralysis. There are exceptions; some members of the Elapidae family cause little or no neurotoxicity but rather severe tissue necrosis (e.g., African spitting cobras). Some vipers cause significant neurotoxicity (e.g., some populations of the Mohave rattlesnake [Crotalus scutulatus]). Physicians should proactively learn the important species in their regions, including how the species can be identified, the expected effects of their venoms, and proper approaches to management.