Chapter 296 Echinococcosis (Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis)

Etiology

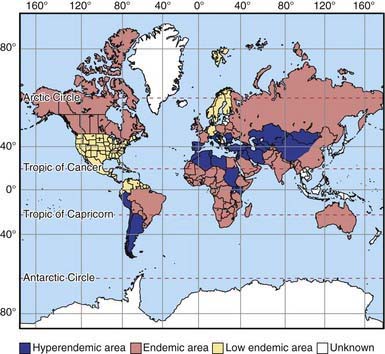

Echinococcosis (hydatid disease or hydatidosis) is the most widespread, serious human cestode infection in the world (Fig. 296-1). Two major Echinococcus species are responsible for distinct clinical presentations, E. granulosus (cystic hydatid disease) and the more malignant E. multilocularis (alveolar hydatid disease). The adult parasite is a small (2-7 mm) tapeworm with only 2-6 segments that inhabits the intestines of dogs, wolves, dingoes, jackals, coyotes, and foxes. These carnivores pass the eggs in their stool, which contaminates the soil, pasture, and water, as well as their own fur. Domestic animals such as sheep, goats, cattle, and camels ingest E. granulosus eggs while grazing. Humans are also infected by consuming food or water contaminated with eggs or by direct contact with infected dogs. The larvae hatch, penetrate the gut, and are carried by the vascular or lymphatic systems to the liver, lungs, and less commonly bones, brain, or heart.

Figure 296-1 Worldwide distribution of cystic echinococcosis.

(From McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, et al: Echinococcosis, Lancet 362:1295–1304, 2003.)