22.1 Ear, nose and throat disorders

• foreign bodies, in any of these areas

• otitis media, both acute and chronic

• hearing loss, both conductive and sensorineural, and congenital and acquired

• rhinosinusitis and its complications

• tonsillitis and suppuration in the neck

Growth and development

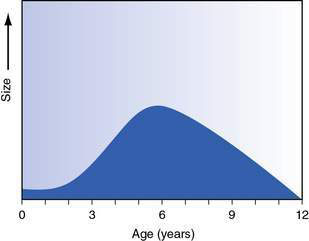

In infants the face is relatively small compared with the cranium, and elongation occurs with mandibular and maxillary growth as the permanent teeth erupt, from about 6 years of age. This coincides with development of the eustachian tube, as it becomes more vertical and functions more efficiently. During this time there is also growth and maturation of the immune system, with enlargement of the tonsils and adenoids; these increase in size until the age of about 7 years, and then start to involute (Fig. 22.1.1).

Fig. 22.1.1 Adenoidal size in relation to age.

Redrawn with permission from Dhillon RS, East CA, 2006 Ear, Nose and Throat and Head and Neck Surgery: An Illustrated Colour Text, 3e. With permission from Elsevier.

The ear

Otitis media

• A child with acute otitis media (AOM) usually presents following a cold with severe pain and fever, and may have otorrhoea. Infants and young children may not localize well and present with fever, irritability and sometimes vomiting.

• Otitis media is common in the first year of life, and 75% of children have had at least one episode by the age of 3 years. Recurrent otitis media is defined as at least three episodes in 6 months or four in 12 months. It is most common in autumn and winter as viral infections cause obstruction of the nose and ET.

• The three common causative organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (non-typeable) and Moraxella catarrhalis.

• The complications of AOM include TM perforation, facial paralysis, mastoiditis, intracranial spread including meningitis and abscess formation, and sigmoid sinus thrombosis.

• A child with mastoiditis has often had symptoms for days before the ear starts to protrude, with erythema and swelling over the mastoid process. The treatment is surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy.

• With unresolved inflammation and eustachian tube obstruction there may be damage and retraction of the TM, with erosion of the ossicles. Retraction pockets form and accumulate keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium, known as a cholesteatoma. This causes bone erosion and usually presents with intermittent otorrhoea with hearing loss. Cholesteatoma may also be congenital and present as a white mass (‘pearl’) behind an intact TM. This may be an incidental finding.

There are some recognized risk factors for otitis media:

• Race – Australian aboriginal children and some Native Americans (Inuit, Apache and Navajo). There are differences in the eustachian tube and immunological response, but socioeconomic factors are also important.

• Craniofacial abnormalities – including cleft palate and Down syndrome.

There are recognized environmental factors, and families can help control these:

• Reduce contact with people with upper respiratory infections, especially large-group childcare centres.

• Avoid tobacco smoke both during and after pregnancy.

• Breastfeed for at least 6 months, preferably 12 months. If bottle-fed, prop the baby up as milk can reflux into the ear if lying flat, causing inflammation.

• Avoid pacifiers/dummies; this is possible from inadvertent sharing in childcare centres.

• Vaccination with the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine reduces the incidence of AOM by 8%.

Chronic otitis media with effusion (COME)

• COME can be present for 3 months and still resolve spontaneously.

• Biofilms (blankets of bacteria in a low metabolic state and enclosed by a polymeric matrix) may contribute, and the organisms are similar to those that cause AOM.

• There is no evidence that treatment with decongestants, antihistamines, nasal steroids or alternative medications will improve the resolution of MEE.

• The hearing changes in COME are often mild (10–15 dB worse) but there is a wide range, and the criteria for what is a significant loss are uncertain.

• Long-term studies indicate that for children with normal development there are no sequelae for language development from COME.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree