Chapter 556 Disorders of Pubertal Development

Depending on the primary source of the hormonal production, precocious puberty may be classified as central (also known as gonadotropin dependent, or true) or peripheral (also known as gonadotropin independent or precocious pseudopuberty) (Table 556-1). Central precocious puberty is always isosexual and stems from hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal activation with ensuing sex hormone secretion and progressive sexual maturation. In peripheral precocious puberty, some of the secondary sex characters appear, but there is no activation of the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal interplay. In this latter group, the sex characteristics may be isosexual or heterosexual (contrasexual; Chapters 577–582).

Table 556-1 CONDITIONS CAUSING PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY

CENTRAL (GONADOTROPIN DEPENDENT, TRUE PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY)

COMBINED PERIPHERAL AND CENTRAL

PERIPHERAL (GONADOTROPIN INDEPENDENT, PRECOCIOUS PSEUDOPUBERTY)

Girls

Boys

INCOMPLETE (PARTIAL) PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY

hCG, human chorionic gonadotropic; SCTAT, sex-cord tumor with annular tubules.

556.1 Central Precocious Puberty

Clinical Manifestations

Sexual development can begin at any age and generally follows the sequence observed in normal puberty. In girls, early menstrual cycles may be more irregular than they are with normal puberty. The initial cycles are usually anovulatory, but pregnancy has been reported as early as 5.5 yr of age (Fig. 556-1). In boys, testicular biopsies have shown stimulation of all elements of the testes, and spermatogenesis has been observed as early as 5-6 yr of age. In affected girls and boys, height, weight, and osseous maturation are advanced. The increased rate of bone maturation results in early closure of the epiphyses, and the ultimate stature is less than it would have been otherwise. Without treatment, approximately 30% of girls and an even larger percentage of boys achieve a height less than the 5th percentile as adults. Mental development is usually compatible with chronological age. Emotional behavior and mood swings are common, but serious psychological problems are rare.

Laboratory Findings

Osseous maturation is variably advanced, often more than 2-3 standard deviations (SD). Pelvic ultrasonography in girls reveals progressive enlargement of the ovaries, followed by enlargement of the uterus to pubertal size. An MRI scan usually demonstrates physiologic enlargement of the pituitary gland, as seen in normal puberty; it may also reveal CNS pathology (Chapter 556.2).

Differential Diagnosis

Gonadotropin-independent causes of isosexual precocious puberty must be considered in the differential diagnosis (see Table 556-1). For girls, these include tumors of the ovaries, autonomously functioning ovarian cysts, feminizing adrenal tumors, McCune-Albright syndrome, and exogenous sources of estrogens. In boys, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal tumors, Leydig cell tumors, chorionic gonadotropin–producing tumors, and familial male precocious puberty should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

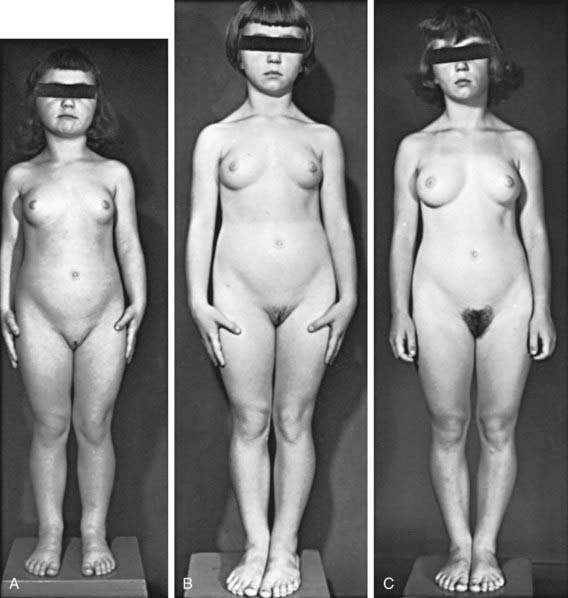

, (B) at

, (B) at  , and (C) at

, and (C) at  yr of age. Breast development and vaginal bleeding began at

yr of age. Breast development and vaginal bleeding began at  yr of age. Bone age was

yr of age. Bone age was  yr at

yr at  and 14 yr at 8 yr of age. Intelligence and dental age were normal for chronological age. Growth was completed at 10 yr; ultimate height was 142 cm (56 in). No effective therapy was available at the time this patient sought medical attention.

and 14 yr at 8 yr of age. Intelligence and dental age were normal for chronological age. Growth was completed at 10 yr; ultimate height was 142 cm (56 in). No effective therapy was available at the time this patient sought medical attention.