Comitant strabismus is the most common type of strabismus. The individual extraocular muscles usually have no defect. The amount of deviation is constant, or relatively constant, in the various directions of gaze.

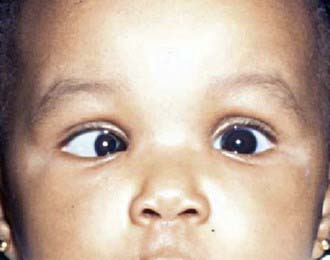

Pseudostrabismus (pseudoesotropia) is one of the most common reasons a pediatric ophthalmologist is asked to evaluate an infant. This condition is characterized by the false appearance of strabismus when the visual axes are aligned accurately. This appearance may be caused by a flat, broad nasal bridge, prominent epicanthal folds, or a narrow interpupillary distance. The observer might see less white sclera nasally than would be expected, and the impression is that the eye is turned in toward the nose, especially when the child gazes to either side. Parents often comment that when their child looks to the side, the eye almost disappears from view. Pseudoesotropia can be differentiated from a true misalignment of the eyes when the corneal light reflex is centered in both eyes and when the cover-uncover test shows no refixation movement. Once pseudoesotropia has been confirmed, parents can be reassured that the child will outgrow the appearance of esotropia. As the child grows, the bridge of the nose becomes more prominent and displaces the epicanthal folds, and the medial sclera becomes proportional to the amount visible on the lateral aspect. It is the appearance of crossing that the child will outgrow. Some parents of children with pseudoesotropia erroneously believe that their child has an actual esotropia that will resolve on its own. Because true esotropia can develop later in children with pseudoesotropia, parents and pediatricians should be cautioned that reassessment is required if the apparent deviation does not improve.

Esodeviations are the most common type of ocular misalignment in children and represent >50% of all ocular deviations. Congenital esotropia is a confusing term. Few children who have this disorder are actually born with an esotropia. Most reports in the literature have therefore considered infants with confirmed onset earlier than 6 mo as having the same condition, which some observers have designated infantile esotropia.

The characteristic angle of congenital esodeviations is large and constant (Fig. 615-1). Because of the large deviation, cross-fixation is often encountered. This is a condition in which the child looks to the right with the left eye and to the left with the right eye. With cross-fixation, there is no need for the eye to turn away from the nose (abduction) because the adducting eye is used in side gaze; this condition simulates a 6th nerve palsy. Abduction can be demonstrated by the doll’s head maneuver or by patching 1 eye for a short time. Children with congenital esotropia tend to have refractive errors similar to those of normal children of the same age. This contrasts with the characteristic high level of farsightedness associated with accommodative esotropia. Amblyopia is common in children with congenital esotropia.

The primary goal of treatment in congenital esotropia is to eliminate or reduce the deviation as much as possible. Ideally, this results in normal sight in each eye, in straight-looking eyes, and in the development of binocular vision. Early treatment is more likely to lead to the development of binocular vision, which helps to maintain long-term ocular alignment. Once any associated amblyopia is treated, surgery is performed to align the eyes. Even with successful surgical alignment, it is common for vertical deviations to develop in children with a history of congenital esotropia. The two most common forms of vertical deviations to develop are inferior oblique muscle overaction and dissociated vertical deviation. In inferior oblique muscle overaction, the overactive inferior oblique muscle produces an upshoot of the eye closest to the nose when the patient looks to the side (Fig. 615-2). In dissociated vertical deviation, 1 eye drifts up slowly, with no movement of the other eye. Surgery may be necessary to treat either or both of these conditions.

It is important that parents realize that early successful surgical alignment is only the beginning of the treatment process. Because many children redevelop strabismus or amblyopia, they need to be monitored closely during the visually immature period of life.

Accommodative esotropia is defined as a “convergent deviation of the eyes associated with activation of the accommodative (focusing) reflex.” It usually occurs in a child who is between 2 and 3 yr of age and who has a history of acquired intermittent or constant crossing. Amblyopia occurs in the majority of cases.

The mechanism of accommodative esotropia involves uncorrected hyperopia, accommodation, and accommodative convergence. The image entering a hyperopic (farsighted) eye is blurred. If the amount of hyperopia is not significant, the blurred image can be sharpened by accommodating (focusing of the lens of the eye). Accommodation is closely linked with convergence (eyes turning inward). If a child’s hyperopic refractive error is large or if the amount of convergence that occurs in response to each unit of accommodative effort is great, esotropia can develop.

To treat accommodative esotropia, the full hyperopic (farsighted) correction is initially prescribed. These glasses eliminate a child’s need to accommodate and therefore correct the esotropia (Fig. 615-3). Although many parents are initially concerned that their child will not want to wear glasses, the benefits of binocular vision and the decrease in the focusing effort required to see clearly provide a strong stimulus to wear glasses, and they are generally accepted well. The full hyperopic correction sometimes straightens the eye position at distance fixation but leaves a residual deviation at near fixation; this may be observed or treated with bifocal lenses, antiaccommodative drops, or surgery.

It is important to warn parents of children with accommodative esotropia that the esodeviation might appear to increase without glasses after the initial correction is worn. Parents often state that before wearing glasses, their child had a small esodeviation, whereas after removing the glasses, the esodeviation becomes quite large. Parents often blame the increased esodeviation on the glasses. This apparent increase is due to a child’s using the appropriate amount of accommodative effort after the glasses have been worn. When these children remove their glasses, they continue to use an accommodative effort to bring objects into proper focus and increase the esodeviation.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Related