The trophoblast produces hormones almost immediately, notably human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) (detected in pregnancy tests), which will peak at 12 weeks. This ability to invade and produce hCG is reflected in gestational trophoblastic disease. Nutrients are gained from the secretory endometrium, which turns deciduous (rich in glycogen and lipids) under the influence of oestrogen and progesterone from the corpus luteum which is maintained by hCG from the trophoblast. Trophoblastic proliferation leads to formation of chorionic villi. On the endometrial surface of the embryo, this villous system proliferates (chorion frondosum) and will ultimately form the surface area for nutrient transfer, in the cotyledons of the placenta. Placental morphology is complete at 12 weeks. A heartbeat is established at 4–5 weeks and is visible on transvaginal ultrasound a week later.

Spontaneous Miscarriage

Definition and Epidemiology

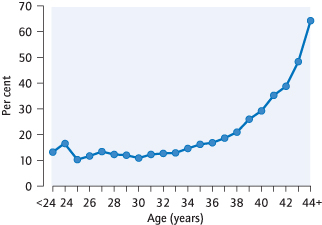

The fetus dies or delivers dead before 24 completed weeks of pregnancy. The majority occur before 12 weeks. Fifteen per cent of clinically recognized pregnancies spontaneously miscarry; more will be so early as to go unrecognized. The rate of miscarriage increases with maternal age (Fig. 14.2).

Types of Miscarriage

Threatened Miscarriage:

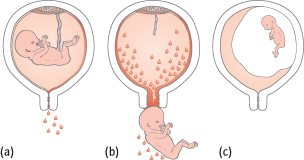

There is bleeding but the fetus is still alive, the uterus is the size expected from the dates and the os is closed (Fig. 14.3a). Only 25% will go on to miscarry.

Inevitable Miscarriage:

Bleeding is usually heavier. Although the fetus may still be alive, the cervical os is open. Miscarriage is about to occur.

Incomplete Miscarriage:

Some fetal parts have been passed, but the os is usually open (Fig. 14.3b).

Complete Miscarriage:

All fetal tissue has been passed. Bleeding has diminished, the uterus is no longer enlarged and the cervical os is closed.

Septic Miscarriage:

The contents of the uterus are infected, causing endometritis [→ p.77]. Vaginal loss is usually offensive, the uterus is tender, but a fever can be absent. If pelvic infection occurs there is abdominal pain and peritonism.

Missed Miscarriage:

The fetus has not developed or died in utero, but this is not recognized until bleeding occurs or ultrasound is performed. The uterus is smaller than expected from the dates and the os is closed (Fig. 14.3c).

Aetiology of Sporadic Miscarriage

Isolated non-recurring chromosomal abnormalities account for >60% of ‘one-off’ or sporadic miscarriages. However, if three or more miscarriages occur, then the rarer recurrent causes are more likely [→ p.121]. Exercise, intercourse, ‘stress’ and emotional trauma do not cause miscarriage.

Clinical Features

History:

Bleeding is usual unless a missed miscarriage is found incidentally at ultrasound examination. Pain from uterine contractions can cause confusion with an ectopic pregnancy.

Examination:

Uterine size and the state of the cervical os are dependent on the type of miscarriage. Severe tenderness is unusual.

Investigations

Early pregnancy assessment units (EPAU) should be available at least 5 days per week and easily accessible by GPs. EPAUs streamline management, reduce costs and the number and duration of admissions.

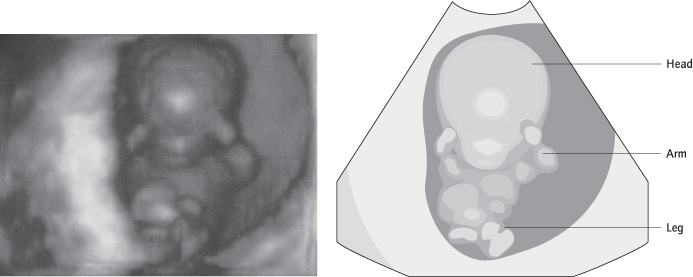

Ultrasound will show if a fetus is in the uterus and if it is viable (Fig. 14.4), and it may detect retained fetal tissue (products). If there is doubt, the scan should be repeated a week later as non-viable pregnancies can be confused with a very early pregnancy, especially where the date of the last menstrual period is uncertain or periods irregular. Ultrasound does not always allow visualization of an ectopic pregnancy, but if a fetus is seen in the uterus, coexistent ectopic pregnancy (heterotopic pregnancy) is extremely unlikely unless conception followed in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment with the replacement of multiple embryos.

Blood Tests:

HCG levels in the blood normally increase by >66% in 48 h with a viable intrauterine pregnancy. This helps differentiate between ectopic and viable intrauterine pregnancies when no intrauterine gestation sac is visible on scan. The full blood count (FBC) and rhesus group should also be checked.

Management

Admission is necessary if ectopic pregnancy is suspected, if the miscarriage is septic or there is heavy bleeding.

Resuscitation is occasionally required. Products of conception in the cervical os cause pain, bleeding and vasovagal shock and are removed via a speculum using polyp forceps. Intramuscular ergometrine will reduce bleeding by contracting the uterus, but is only used if the fetus is non-viable. If there is a fever, swabs for bacterial culture are taken and intravenous antibiotics are given. Anti-D is given to women who are rhesus negative if the miscarriage is treated surgically or medically, or if there is bleeding after 12 weeks’ gestation. This reduces the risk of isoimmunization and rhesus disease in future pregnancies [→ p.198].

Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy (Threatened Miscarriage)

Ninety per cent of women in whom fetal heart activity is detected at 8 weeks will not miscarry. Bed rest or hormone treatment with progesterone or hCG do not prevent miscarriage.

Non-Viable Intrauterine Pregnancy

Options include expectant, medical or surgical management (BMJ 2006; 332: 1235–40).

Expectant management can be continued as long as the woman is willing and there are no signs of infection. It is successful within 2–6 weeks in >80% of women with incomplete miscarriage and in 30–70% of women with missed miscarriage. A large intact sac is associated with lower success rates.

Medical management is with prostaglandin (oral, sublingual or vaginal) sometimes preceded by the oral antiprogesterone mifepristone. Medical management is successful in >80% of women with incomplete miscarriage (similar to expectant management) and 40–90% of women with missed miscarriage.

Surgical Management:

Evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC) under anaesthetic using vacuum aspiration. Evacuation is suitable if the woman prefers it, if there is heavy bleeding or signs of infection (performed under antibiotic cover). Success rates are >95% for both incomplete and missed miscarriage. Tissue is examined histologically to exclude molar pregnancy.

Complications

Vaginal bleeding with expectant or medical management can be heavy and painful so women must have 24 h direct access to an emergency gynaecological service for advice/ treatment. Risks of expectant and medical management include the need for surgical evacuation (10–40%). Infection rates are similar (3%) between expectant, medical or surgical management. If infection becomes systemic, endotoxic shock occasionally ensues, with hypotension, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Surgical evacuation can partially remove the endometrium causing Asherman’s syndrome [→ p.17] or perforate the uterus (<1%). Long-term conception rates do not differ between the management options (BMJ 2009; 339: b3827). Surgical management is more expensive.

Counselling After Miscarriage

Patients should be told that the miscarriage was not the result of anything they did or did not do and could not have been prevented. Reassurance as to the high chance of successful further pregnancies is important. Referral to a support group may be useful (www.miscarriageassociation.org.uk). Because miscarriage is so common, further investigation is usually reserved for women who have had three miscarriages.

Recurrent Miscarriage

Definition and Epidemiology

Recurrent miscarriage is when three or more miscarriages occur in succession; 1% of couples are affected. The chance of miscarriage in a fourth pregnancy is still only 40%, but a recurring cause is more likely and investigations and support should be arranged (NEJM 2010; 363: 1740–7).

Causes and Their Management

Whilst investigation may reveal a possible cause, few treatments are of proven value. These patients are often extremely distressed and support is vital. This involves emotional support for both partners in the form of counselling as well as a clearly defined management plan during pregnancy in terms of ultrasound monitoring (Hum Reprod 2011; 26: 873–7). In later pregnancy, ‘high-risk’ monitoring is important because late pregnancy complications are more common.

Antiphospholipid antibodies can cause recurrent miscarriage. Thrombosis in the uteroplacental circulation is likely to be the mechanism. Treatment is with aspirin and low-dose low molecular weight heparin (Curr Opin Rheum 2011; 23: 299–304).

Chromosomal defects are found in only 4% of couples. Parental karyotyping is therefore usual and translocations may be found leading to an increased proportion of chromosomally imbalanced sperm or oocytes, and therefore embryos. Referral to a clinical geneticist allows for full explanation of the findings and a discussion regarding karyotyping of other family members who may have inherited the same rearrangement. Prenatal diagnosis using chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis is offered. The use of donor oocytes or sperm (all donors are routinely karyotyped), or preimplantation genetic screening (PGS) of IVF embryos is an alternative option.

Anatomical Factors:

Uterine abnormalities are diagnosed with ultrasound (or hysterosalpingogram though this is more invasive). They are more common with late miscarriage. Many, however, are incidental findings and surgical treatment could lead to uterine weakness or adhesion formation. Cervical incompetence [→ p.205] is a recurrent cause of late (>16 weeks) miscarriage as well as preterm labour.

Infection:

This is not a cause of recurrent early miscarriage but is implicated in preterm labour and late (>16 weeks) miscarriage, where treatment of bacterial vaginosis reduces the incidence of fetal loss [→ p.171].

Others:

Obesity, smoking, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), excess caffeine intake and higher maternal age have been implicated.

Investigation of Recurrent Miscarriage

Antiphospholipid antibody screen (repeat at 6 weeks if positive)

Karyotyping of both parents

Pelvic ultrasound (or hysterosalpingogram [HSG])

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree