Chapter 651 Diseases of the Dermis

Keloid

Clinical Manifestations

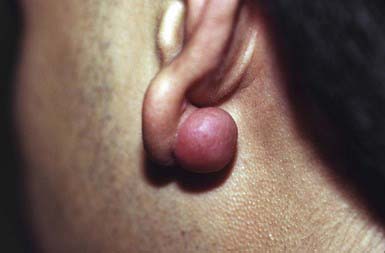

A keloid is a sharply demarcated, benign, dense growth of connective tissue that forms in the dermis after trauma. The lesions are firm, raised, pink, and rubbery; they may be tender or pruritic. Sites of predilection are the face, earlobes (Fig. 651-1), neck, shoulders, upper trunk, sternum, and lower legs. In both keloids and hypertrophic scars, new collagen forms over a much longer period than in wounds that heal normally.

Striae Cutis Distensae (Stretch Marks)

Clinical Manifestations

These thinned, depressed, erythematous bands of atrophic skin eventually become silvery, opalescent, and smooth. They occur most frequently in areas that have been subject to distention, such as the lower back (Fig. 651-2), buttocks, thighs, breasts, abdomen, and shoulders.

Granuloma Annulare

Clinical Manifestations

This common dermatosis occurs predominantly in children and young adults. Affected children are usually healthy. Typical lesions begin as firm, smooth, erythematous papules. They gradually enlarge to form annular plaques with a papular border and a normal, slightly atrophic or discolored central area up to several centimeters in size. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body, but mucous membranes are spared. Favored sites include the dorsum of the hands (Fig. 651-3) and feet. The disseminated papular form is rare in children. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare tends to develop on the scalp and limbs, particularly in the pretibial area. These lesions are firm, usually nontender, skin-colored nodules. Perforating granuloma annulare is characterized by the development of a yellowish center in some of the superficial papular lesions as a result of transepidermal elimination of altered collagen.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

Clinical Manifestations

This disorder manifests as erythematous papules that evolve into irregularly shaped, sharply demarcated, yellow, sclerotic plaques with central telangiectasia and a violaceous border. Scaling, crusting, and ulceration are frequent. Lesions develop most commonly on the shins (Fig. 651-4). Slow extension of a given lesion over the years is usual, but long periods of quiescence or complete healing with scarring may occur.

Lichen Sclerosus

Clinical Manifestations

Lichen sclerosus manifests initially as shiny, indurated, ivory-colored papules, often with a violaceous halo. The surface shows prominent dilated pilosebaceous or sweat duct orifices that often contain yellow or brown plugs. The papules coalesce to form irregular plaques of variable size, which may develop hemorrhagic bullae in their margins. In the later stages, atrophy results in a depressed plaque with a wrinkled surface. This disorder occurs more commonly in girls than in boys. Sites of predilection in girls are the vulvar (Fig. 651-5), perianal, and perineal skin. Extensive involvement may produce a sclerotic, atrophic plaque of hourglass configuration; shrinkage of the labia and stenosis of the introitus may result. Vaginal discharge precedes vulvar lesions in approximately 20% of patients. In boys, the prepuce and glans penis are often involved, usually in association with phimosis; most boys with the disorder were not circumcised early in life. Sites elsewhere on the body that are most commonly involved include the upper trunk, the neck, the axillae, the flexor surfaces of wrists, and the areas around the umbilicus and the eyes. Pruritus may be severe.

Differential Diagnosis

In children, lichen sclerosus is most frequently confused with focal morphea (Chapter 154), with which it may coexist. In the genital area, it may be mistakenly attributed to sexual abuse.

Morphea

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Morphea is a sclerosing condition of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue of unknown etiology.

Clinical Manifestations

Morphea is characterized by solitary, multiple or linear circumscribed areas of erythema that evolve into indurated, sclerotic, atrophic plaques (Fig. 651-6), later healing, or “burning out” with pigment change. It is seen more commonly in females. The most common types of morphea are plaque and linear. Morphea can affect any area of skin. When confined to the frontal scalp, forehead, and midface in a linear band, it is referred to as en coup de sabre. When located on one side of the face, it is called progressive hemifacial atrophy. These forms of morphea carry a poorer prognosis because of the associated underlying musculoskeletal atrophy that can be cosmetically disfiguring. Linear morphea over a joint may lead to restriction of mobility (Fig. 651-7). Pansclerotic morphea is a rare severe disabling variant.