Diagnostic and Operative Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is emerging as an alternative to laparotomy for the definitive diagnosis and treatment of surgical conditions arising in pregnancy. Adhesion formation, pain-related hypoventilation, atelectasis, anorexia, and delayed intestinal function and ambulation are much less common following laparoscopy (Lundorff and associates, 1991). Consequently, the risk for morbid sequelae associated with these factors is reduced.

Unlike laparotomy, laparoscopy requires abdominal wall elevation. Carbon dioxide pneumatic distension is the dominant modality in current practice because of its low combustibility, rapid absorption, and low cost. Unresolved controversy surrounds the use of carbon dioxide as a peritoneal distension medium and centers on the immediate and delayed fetal effects of pneumoperitoneum-mediated pelvic vascular compression and transperitoneal carbon dioxide absorption. Prospective studies are lacking. However, the growing body of literature on pneumoperitoneum-laparoscopy in pregnancy does not reflect a teratogenic or otherwise detrimental effect of carbon dioxide on human newborns. Gasless abdominal wall elevation by mechanical lifting arms avoids these concerns. In addition, it permits the use of regional anesthesia for lower abdominal and pelvic procedures.

Training and credentialing in laparoscopic techniques is not yet standardized. In fact, the multitude of technical variations for specific procedures displayed in textbooks and presentations, demonstrates that there are many feasible approaches to common surgical conditions. Nonetheless, expertise in laparoscopic methods is best gained in an incremental fashion under the supervision of experienced laparoscopists. Difficult cases should not be undertaken until less challenging conditions have been mastered.

The potential for iatrogenic uterine trauma places restrictions on techniques of laparoscopic entry and uterine manipulation that can safely be used in pregnancy. In late pregnancy, the enlarged uterus obscures the pelvic sidewalls and limits exposure in the pelvis and lower abdomen. Perioperative management considerations (eg, antibiotic use, thromboembolism prophylaxis, fetal monitoring, and tocolysis) do not differ from laparotomy-derived protocols.

HISTORY

Ott, of St. Petersburg, reported the first laparoscopic procedure in 1901. The method, dubbed ventroscopy, involved the insertion of a speculum with an attached electric light through a posterior colpotomy incision. Exposure was generated by placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position and by raising the abdomen with tenacula, allowing air to enter through the colpotomy to separate the organs of the abdomen and pelvis.

Later in 1901, Kelling, of Dresden, described and demonstrated the use of a cystoscope with air distension via syringe to examine the peritoneal cavity of a dog—a method he termed coelioscopy. Jacobaeus, of Stockholm, described the first use of the cystoscope to examine the human peritoneal and thoracic cavities, and coined the terms laparoscopy and thoracoscopy, respectively, in 1910.

For several decades thereafter, laparoscopy was advanced primarily by internists seeking to refine the diagnosis of tuberculosis and liver disease. The first operative procedures were liver biopsies, reported by Kalk, a Berlin surgeon, in 1929. Ruddock, of Los Angeles, developed similar procedures in the United States, in the 1930s and 1940s, and introduced the first operative laparoscope in 1934.

Palmer, of France, developed gynecologic laparoscopy in the 1950s. In the 1960s, laparoscopic tubal sterilization by electrosurgery was perfected by Palmer, by Steptoe, in England, and by Cohen, Taylor, and Kass, of Chicago (Chatman and Cohen, 1990). The growing demand for sterilization in the 1970s popularized laparoscopy among American gynecologists.

Advanced operative laparoscopy was pioneered by Semm, of Kiel, beginning in 1974, with techniques for extensive adhesiolysis, coagulation of endometriosis, ovarian cystectomy, and correction of ampullary tubal stenosis. Bruhat, of France, introduced laparoscopic surgery for tubal pregnancy in 1980. Reich performed the first laparoscopic hysterectomy in 1988.

The application of laparoscopy to general surgery began in 1985 with Muhe, of Germany, who reported the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy before the German Surgical Society the following year. His work was followed by that of Mouret and Dubois, of Paris, in 1987, and by McKernan, Saye, Reddick, and Olsen, among others, in the United States in 1988.

ADVANTAGES

The main advantage of laparoscopy over laparotomy is a reduction in the postoperative morbidity that is specifically related to the adverse physiologic responses to surgery (Table 26-1). Secondary benefits include reduced postoperative discomfort, hospitalization time, postoperative morbidity, and a faster return to normal activity (Gadacz, 1993). Randomized, prospective animal and human studies have demonstrated decreased adhesion formation with laparoscopic surgery (Luciano and associates, 1989; Lundorff and associates, 1991). For obese patients, who traditionally have demonstrated a high frequency of wound complications, the prospect of avoiding laparotomy carries great potential benefit.

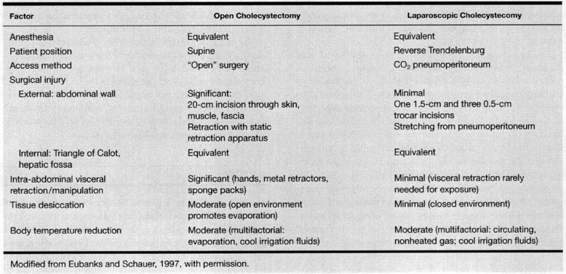

TABLE 26-1. Factors that May Account for Different Physiologic Responses Between Open and Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Technical advantages include optical magnification, enhanced illumination, and improved visualization of small structures throughout the peritoneal cavity. In addition, the smaller size of laparoscopic instrumentation and the magnified view facilitate delicate and precise dissection and hemostasis.

INDICATIONS

ACUTE ABDOMEN

In experienced hands, many acute abdominal conditions are treated laparoscopically. Acute abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom in the pregnant surgical patient (Tarraza and Moore, 1997). The frequency of non-obstetric intra-abdominal surgery in two large institutional reviews was between 0.16 and 0.2 percent (Kort and associates, 1993; Allen and associates, 1989). The most frequent indications for surgery in these studies were appendicitis, adnexal mass, and cholecystitis.

CHOLECYSTITIS. The decision to proceed with surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis should be based upon the same criteria that are used to make the decision with non-pregnant patients. There should be no reluctance to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy upon the pregnant patient. A large body of literature supports the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in pregnancy (Tarraza and Moore, 1997) and successful third-trimester operations have been reported by various authors (Eichenberg and associates, 1996; Geburz and Peetz, 1997).

Meta-analysis of 78,747 laparoscopic cholecystectomies versus 12,973 open cholecystectomies suggested lower mortality (0.086–0.16 vs. 0.66–0.74 percent), but higher common bile duct injury rates (0.36–0.47 vs. 0.19–0.29 percent) with the former (Shea and associates, 1996). The same study found that most conversions followed operative discoveries that were not the result of injuries.

APPENDICITIS. Experience with laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnancy has demonstrated excellent outcomes (Schreiber, 1990) although the convalescent impact of the traditional open approach is typically mild (Attwood and associates, 1992). The main advantage of laparoscopy for suspected appendicitis is the superiority of the laparoscope over a small right lower quadrant incision in evaluating the entire peritoneal cavity—especially when the appendix is grossly normal in appearance.

Laparoscopic appendectomy in general has been compared to open appendectomy in numerous randomized, prospective trials in patients with suspected appendicitis. A review of 10 such studies found that the laparoscopic approach is associated with longer operating times (8–29 minutes additional), a reduced risk of wound infection (odds ratio 2.6), no increase in other complications, a minimal reduction in hospital stay, and an earlier return to normal activity (McCall and associates, 1997). These findings are counterbalanced by prospective data that demonstrate that early discharge after open appendectomy results in a median postoperative stay of 48 hours, and a return to normal activity by 2 weeks in more than 75 percent of 116 consecutive patients (Lord and Sloane, 1996).

A retrospective study of 1287 appendectomies performed for acute, gangrenous, and perforated appendicitis, of which 108 were laparoscopic, suggests a trend toward increased postoperative intra-abdominal abscess formation with laparoscopic appendectomy for perforated appendicitis (Tang and associates, 1996).

ADNEXAL TORSION. Several series document the safety and efficacy of detorsion, observation for reperfusion, and subsequent cystectomy, adnexectomy, or no further treatment based upon the presence of infarction or suspected pathology for both laparoscopy and laparotomy (Bider, 1991; Mage, 1989; Morice, 1997; and their associates). An obviously gangrenous adnexum should not be detorsed (Mage and associates, 1989). Some surgeons recommend stabilization of detorsed adnexa (Nichols and Julian, 1985). When surgery involves excision of the corpus luteum in the first 7 weeks of pregnancy, progesterone replacement therapy should be instituted (Csapo and associates, 1973).

ADNEXAL MASS

Numerous case reports and small series from various centers attest to the feasibility and effectiveness of laparoscopic treatment of adnexal masses in pregnancy (Parker and associates, 1996; Pelosi and associates, 1997a; Soriano and associates, 1999).

In the absence of acute abdominal pain, adnexal masses are best treated in the early second trimester when the risks for pregnancy loss and preterm delivery are least and when the gravid uterus has not reduced exposure to the adnexa. When malignancy is suspected, oncologic consultation is recommended for prompt and adequate staging. Suspected benign masses should be operated in a setting where accurate frozen section analysis is available and, for cystic tumors, in a manner which reduces the risk for intraperitoneal spill of fluid contents. Spillage of benign fluid may produce chemical peritonitis (Canis and associates, 1994; Parker and associates, 1996), while spillage of malignant fluid may predicate the necessity for adjuvant chemotherapy (Chi and Curtin, 1999).

HETEROTOPIC PREGNANCY

From Duverney’s first report in 1708 through the early 1970s, spontaneous combined intrauterine and tubal gestation had an incidence of 1 in 30,000 pregnancies. With the advent of assisted reproductive technologies, treated patients carry a heterotopic gestation risk of 1 in 100 pregnancies (Tal and associates, 1996), and with early intervention, up to 70 percent of intrauterine gestations have been salvaged (Rojansky and Schenker, 1996).

The majority of patients are diagnosed prior to the onset of symptoms due to the close sonographic surveillance employed with assisted reproductive technologies. Sonographic-assisted and laparoscopic instillation of feticidal or placentotoxic substances and hyperosmolar glucose have successfully been used (Strohmer and associates, 1998). Salpingectomy eliminates the theoretical concern that such substances may have untoward effects upon the intrauterine pregnancy. Cornual heterotopic pregnancies have been managed using the laparoscope as either a diagnostic or operative tool (Vilos, 1995).

UNCOMMON INDICATIONS

The laparoscopic treatment of several rare conditions has been reported. Experience with these operations in the pregnant patient is extremely limited and included only with the proviso that they currently have no defined role in standard practice.

SYMPTOMATIC LEIOMYOMAS. Myomectomy in pregnancy, by any route, is seldom indicated. Safe myomectomy in pregnancy is limited to excision of pedunculated tumors. Reports of laparoscopic myomectomy in pregnancy have involved either suture ligation (Luxman and associates, 1998) or bipolar electrosurgical desiccation (Pelosi and associates, 1995), and scissors transection of the myoma stalk with subsequent uncomplicated term deliveries.

INCARCERATED UTERUS. In a review of incarceration of the gravid uterus, two cases of successful early second trimester laparoscopic-assisted uterine reduction were reported, followed subsequently by vaginal delivery at term (Lettieri and associates, 1994). In both cases, the authors reported that the creation of a laparoscopic pneumoperitoneum alone led to an effortless manual disimpaction of the fundus from the cul-de-sac where previous conventional attempts under anesthetic relaxation had failed.

PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA. In the majority of cases, pheochromocytoma is benign and involves the adrenal glands. Laparoscopic right adrenalectomy at 18 weeks of gestation was recently reported in a patient with pheochromocytoma-related hypertension (Demeure and associates, 1998). The patient delivered uneventfully at term.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

There are various situations in which diagnostic laparoscopy may reveal a condition feasibly treatable by operative laparoscopy, but best approached by laparotomy, and conditions in which unforeseen surgical complications or equipment malfunction warrant conversion to laparotomy. Surgical skill plays a much greater role in laparoscopic operations due to a lack of standardized techniques and formal training. The threshold between feasible and advisable courses of action varies between surgeons and over time. Prolonged operations should be avoided.

Because laparoscopic surgery may be performed by either pneumoperitoneum-mediated or gasless mechanical elevation of the abdominal wall, and because steep tilting of the patient may be required for certain operations, but not others, contraindications to these components should be considered separately. The surgeon should keep in mind that gasless laparoscopy may readily circumvent contraindications to pneumoperitoneum.

Absolute contraindications to pneumoperitoneum are increased intracranial pressure, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, peritoneojugular shunt, and congestive heart failure (Joris, 1994). Others include hypovolemic shock and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Exposure may be inadequate for laparoscopic surgery in the presence of severe, dense adhesions as frequently seen following previous abdominopelvic radiation, and multiple operations for either ruptured abscesses, inflammatory bowel disease with fistula, and tuberculosis (Kadar, 1995). Bowel obstruction with massively dilated bowel also precludes adequate laparoscopic surgical exposure.

Sepsis is a relative contraindication to carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum based upon animal data, which suggests that hemodynamic compromise, albeit tolerable, occurs in this setting (Greif and Forse, 1998). Gasless laparoscopy does not produce this effect and consequently, may be an alternative when available (Koivusalo and associates, 1997). Advanced inflammatory conditions of the appendix (gangrene, phlegmon, abscess) are considered an indication for conversion to laparotomy by most surgeons (Hunter, 1998).

FACTORS DEMANDING CAUTION

Beyond consideration of the diagnosis prompting surgical intervention, the laparoscopist must be wary of factors that may complicate laparoscopic access and exposure. In addition, the limitations of the laparoscopic approach must always be kept in mind (Table 26-2).

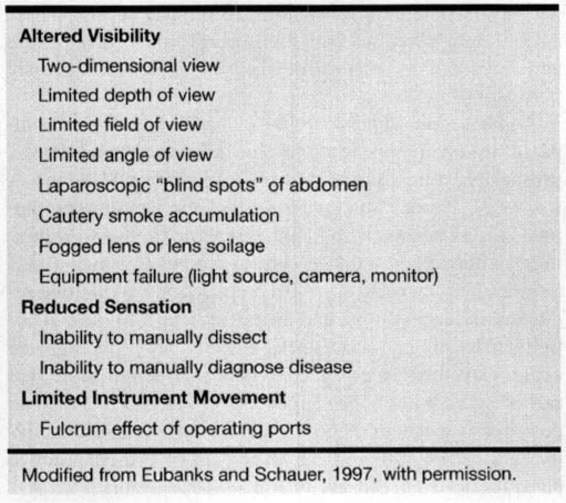

TABLE 26-2. Inherent Features of Laparoscopy that May Precipitate Complications

OBESITY. Obesity predisposes to anatomic distortion of the abdominal wall and increased intraperitoneal pressures beneath the weight of a large panniculus. Assessment of the position of the umbilicus—the preferred site of entry—in relation to underlying structures and correction for any deviation, is necessary for safe laparoscopic entry and for subsequent therapy (Pelosi and Pelosi, 1998; Hurd and associates, 1991). Also, caution is required in manipulating secondary instruments against the resistance of a thickened abdominal wall. Nonetheless, surgical series in experienced hands demonstrate excellent therapeutic results in this group of patients (Pelosi and Pelosi, 1998).

PRIOR ABDOMINAL/PELVIC SURGERY. A history of previous abdominal or pelvic surgery is a well-known risk factor for the presence of intraperitoneal adhesions. When surgical scars are present in proximity to the umbilicus, concern for the presence of adherent bowel or omentum immediately beneath the laparoscopic entry site is warranted. Mechanical bowel preparation with oral and rectal instillations is prudent to decrease the bacterial content of the intestinal tract should bowel injury occur. Open laparoscopy is the entry method of choice in such patients permitting visual and tactile assessment of local adhesions and prompt identification and repair of entry related injury (Pelosi and Pelosi, 1995; Hasson, 1971). Laparoscopic entry 3 cm inferior to the subcostal arch in the left mid-clavicular line has been recommended by others as a site rarely complicated by adhesions (Palmer, 1974; Chang and associates, 1995).

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE. Mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is not a contraindication to pneumoperitoneum. To the contrary, the reduced postoperative respiratory dysfunction associated with laparoscopy favors this approach. Nonetheless, a low-pressure pneumoperitoneum is recommended because of a limited ability to compensate for hypercarbia (Peters and Kavoussi, 1998).

PREGNANCY-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

INITIAL EVALUATION

A thorough history and physical examination should emphasize antenatal medical complications (eg, cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus) and prior surgical procedures. Pertinent laboratory analysis should be performed, with results adjusted to reflect the normative values of pregnancy. Pre-operative ultrasound assessment for fetal viability and lethal anomalies is desirable. Vaginal bleeding, if present, mandates a thorough search for its source, including placental localization and the exclusion of placenta previa or abruptio.

TIMING OF SURGERY

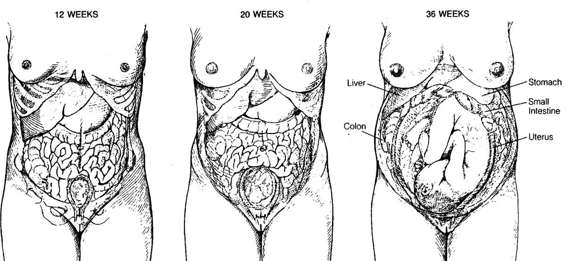

The optimal timing for intraabdominal surgery is early in the second trimester. This timing avoids the higher incidence of spontaneous abortion seen during the first trimester and of the preterm labor, which is seen more commonly in the late second and third trimesters. Operative field exposure is also excellent and not yet compromised by encroachment of the gravid uterus into the mid- and upper abdomen (Fig. 26-1).

FIGURE 26-1. Progressive displacement of the abdominal organs in pregnancy. (Reproduced with permission from Brooks DC, Feinberg BB. Pregnancy. Approach to abdominal pain in pregnant patients. In: Scientific American Care of the Surgical Patient. New York: Scientific American, 1993.)

FETAL CONSIDERATIONS

ANESTHETIC RISK. The intra-abdominal process itself often represents a very real risk to the well-being of the patient and of the pregnancy; however, the risk of the anesthetic, whether conduction or general, appears to be nil. Early reports that general anesthesia was associated with spontaneous abortion with first trimester exposure failed to control for the intraabdominal surgical disease process per se or for its severity (Knill-Jones and associates, 1975). When extensive uterine manipulation, upper abdominal exploration or the use of a pneumoperitoneum are anticipated, a general anesthetic is preferred both for its superior uterine relaxant properties and for maternal comfort and safety. Enflurane, isoflurane, and halothane all possess excellent myometrial muscle relaxant properties.

FETAL/TERATOGENIC RISK. Carbon dioxide is the gas most frequently used to establish a pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopy. A study of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum in pregnant ewes demonstrated no adverse effect from increased pressure alone, but fetal hypercarbia, acidosis, increased fetal arterial pressure, and possible tachycardia associated with the use of carbon dioxide (Hunter and associates, 1995). It was postulated that carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum may increase the maternal partial pressure of carbon dioxide, producing impaired carbon dioxide exchange across the placenta and worsening the mild respiratory acidosis typically maintained by the fetus (Hunter and associates, 1995). Studies on the possible adverse effects of excessive exposure are few and do not adequately model the exposure seen with laparoscopy. Cardiac anomalies have been reported in pregnant rats exposed to 3 percent carbon dioxide and dental defects with exposures to as high as 30 percent ambient carbon dioxide (Haring, 1960; King and associates, 1962). Vertebral anomalies in the offspring of rabbits exposed to 8 percent ambient carbon dioxide for 1–2 days have also been reported (Shepard, 1986). Nitrous oxide administered over 1–2 days at 50 percent concentration has also been associated with increased spontaneous abortions, skeletal deformities, and small-for-gestational-age babies (Pederson and Finster, 1979). However, even the most radical laparoscopic procedures are completed in less than 1 day.

The theoretic potential for the dispersion of electrosurgical current to the fetus has not been studied, but would expectedly be least with bipolar versus unipolar current. Nonetheless, the direct delivery of a 10-W unipolar current directly into the body of acardiac twins with subsequent term delivery of apparently healthy surviving twins was recently reported in four women (Rodeck and associates, 1998). The creation of potentially noxious gases, especially carbon monoxide, is another concern with electrosurgery. One study in nonpregnant women demonstrated no increase in carboxyhemoglobin levels in prolonged operative laparoscopy and attributed the results to rapid smoke evacuation (Nezhat and associates, 1996).

NEONATAL MORBIDITY/MORTALITY. Counseling patients regarding the potential perioperative increase in fetal morbidity and mortality should be based upon institution-specific outcomes data, if they are available. Prognosis for fetal survival and neonatal outcomes requires accurate knowledge of gestational age and fetal weight (Phelan, 1990). Comparative analysis between laparoscopy and laparotomy using the Swedish Health Registry demonstrated no differences between the two modalities with regard to birth weight, gestational duration, growth restriction, infant survival, and fetal malformations (Reedy and associates, 1997). However, in comparison to the total obstetric population, both groups demonstrated an increased risk for birthweight <2500 g, delivery before 37 weeks, and growth restriction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree