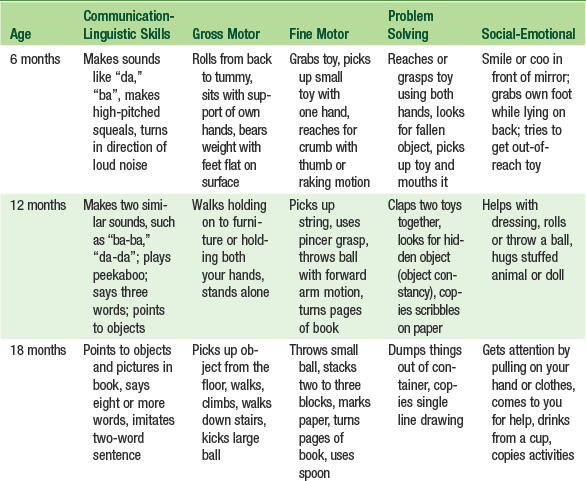

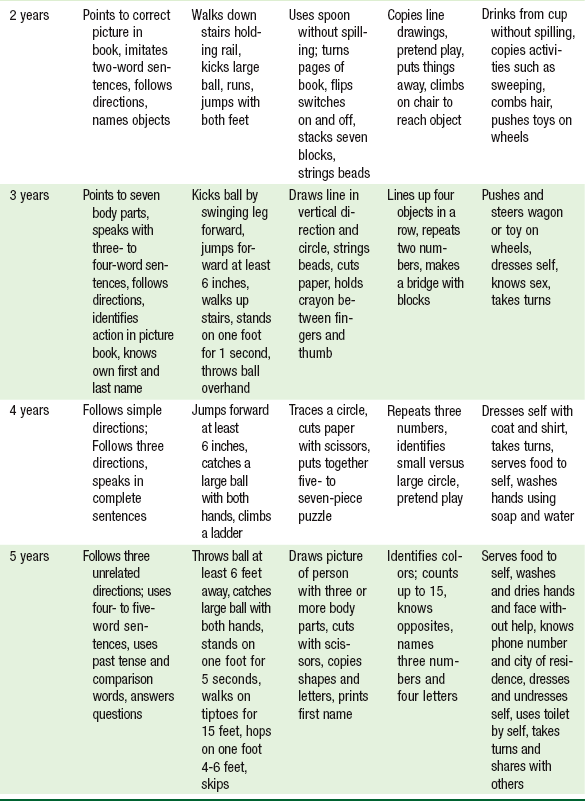

CHAPTER 3 Each child achieves developmental milestones at his or her own pace, although the sequence of developmental milestones is generally incremental and stepwise in all children. Screening children for developmental delay and emotional and behavioral difficulties is one of the most challenging aspects of well-child care. Screening is an important step toward referral for evaluation and diagnosis of developmental delay and emotional and behavioral problems, and health care professionals are mandated by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Title V of the Social Security Act to provide screening, early identification, and intervention for children with developmental delays and disabilities.1 In the United States, 12% to 16% of children have at least one developmental delay.2 The most common childhood developmental and behavioral problems identified are speech and language delay, hearing loss, emotional and behavioral concerns, learning disabilities, delay in developmental milestones, and mental retardation.3 Health care providers can identify young children with developmental and mental health problems early in life by providing surveillance at every well-child visit and implementing standardized developmental screening tests at the 9-month, 18-month, and 24- or 30-month well-child visit.1 Timely identification of developmental and behavioral problems and prompt referral for early intervention can lead to interventions that resolve or lessen the impact of a delay or disability on the functioning of the child and family. Effective interventions in early childhood increase a child’s readiness for school entry and for optimum learning in the classroom. Surveillance for vision and hearing includes asking parents about any concerns they may have about their infant or young child’s developing vision or response to voices or sounds in the environment. Observable normal visual behaviors include fixing on and following near faces at 6 to 8 weeks of age; visually tracking at 4 months of age, including seeing the parent or caregiver at a distance of 5 feet; and visually fixating at 5 months on a 1-inch cube or small object at 12 inches.4 Health care providers should ask parents about their child’s ability to hear quiet sounds and turn and locate voices. All children referred for emotional and behavioral concerns should also have formal vision and hearing screening tests conducted to identify deficits or delays. Reviews of screening practices for vision and hearing are presented in Chapters 11 and 12, respectively. Speech refers to the mechanics of oral communication, and language encompasses the understanding, processing, and production of communication during the early developmental years and throughout childhood. Surveillance of speech and language skills in childhood includes eliciting any parental concerns about communication problems, dysfluency, stuttering, articulation disorders, or an unusual voice quality.5 Approximately 10% to 15% of children 2 years of age have language delays, and 4% to 5% remain language delayed after 3 years of age.6 Early referral and intervention is key to optimizing speech and language development in early childhood. Health care providers need to conduct ongoing surveillance at each health encounter and identify children with parental concerns about speech and language development. Table 3-1 presents normal developmental speech and language patterns in infancy and early childhood. TABLE 3-1 Normal Range of Developmental Speech and Language Patterns in Infancy and Early Childhood Data from Sharma A: Developmental examination: birth to 5 years, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 96:162-175, 2011; Davies D: Child development: a practitioner’s guide, ed 3, New York, 2011, Guildford Press. As a component of developmental surveillance for language deficits, pediatric health care providers can promote literacy by adopting the Reach Out and Read (ROR) program. ROR was designed to target children in early childhood who are at risk for poor early school performance and to provide families with books and anticipatory guidance about the importance of reading to young children. Several studies have shown that ROR can significantly enhance a young child’s early literacy environment by increasing the frequency of parent-child book-sharing activities and facilitating language development.7 Pediatric health care settings interested in establishing a pediatric literacy promotion program may contact the national Reach Out and Read program at http://www.reachoutandread.org. The clinical assessment or surveillance of development without using standardized developmental screening tests identifies less than 50% of children with developmental delays.8 The ultimate goal of developmental surveillance and screening is to improve outcomes for children with developmental delays and disorders. Table 3-2 presents normal developmental milestones of communication, fine and gross motor, problem solving, and social/emotional skills from 6 months to 5 years of age in accordance with Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ-3) (2009). Guidelines for developmental surveillance and developmental screening are available at the website for the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (http://brightfutures.aap.org).9 TABLE 3-2 ASQ-3 Developmental Milestones by Age Data from Squires J, Bricker D: Ages and stages questionnaires, ed 3 (ASQ-3), Baltimore, MD, 2009, Brookes Publishing. Certain biological, family, and social risk factors increase the likelihood that a child will exhibit developmental delay. Biological factors that influence development include prenatal factors such as maternal substance abuse, maternal infection, maternal chronic health conditions, maternal medications, and severe toxemia. Neonatal risk factors include history of prematurity, gestational age <33 weeks, birth weight <1500 g, Apgar score <3 at 5 minutes, neonatal infections (sepsis or meningitis), and severe hyperbilirubinemia. A family history of maternal depression, low maternal education, poverty, a lack of maternal bonding, child abuse and neglect, and a lack of developmentally appropriate opportunities for learning can impact early child development. Environmental factors such as disadvantaged neighborhoods, high lead levels, exposure to environmental toxins, and limited access to health care may also contribute to developmental delays.4 Children at risk require especially diligent developmental surveillance, including implementing recommended use of developmental screening tools in the first 3 years of life and prompt referral for early intervention services, including a pediatric neurologist or pediatric developmental specialist when indicated. Box 3-1 presents red flags for developmental delay and language delay in infancy and early childhood that warrant referral for early intervention.

Developmental surveillance and screening

Developmental surveillance in early childhood

Age

Preverbal Communication to Developing Language and Attention to Speech Sounds

8 weeks

Grunting, crying, cooing

4 months

Squeals, yells, repeating vowel sounds or sounds in repeated patterns

Turns head to look at the speaker by 4 months

6 months

More complex consonant-vowel combinations (“da,” “ba”)

Vocal play with parent or caregiver repeating sounds

Responding to own and family names by 6 months

8 to 10 months

Multisyllable babble (vowel-consonant combinations)

Appears to listen to conversation of others by 8 months

Looks at or gives common objects used at home by 8 months

Wordlike sounds with intonation by 9 months

Jargon

Waves bye-bye and/or plays pat-a-cake by 10 months

10 to 12 months

Infant learned favored sounds of parent’s and caregiver’s language

12 to 13 months

Emergence of first word ranges from 8 to 18 months (mean 13 months)

Consonant-vowel word by 12 months

Single words, other than mama/dada, with consistent meaning by 12-13 months

Infant communicates actively by pointing

13 to 15 months

Follows familiar requests by 12 to 15 months

18 to 20 months

Understands about 50 words

Speaks about 20 words

24 months

Median speaking vocabulary 300 words

10th percentile speaking 60 words

90th percentile speaking 500 words

Developmental risk factors

Developmental surveillance and screening